Interviews with filmmakers Hasan Oswald and Amjad Al Rasheed underpin this overview of three Middle Eastern films at the 2024 Human Rights Watch Film Festival, screening in London from March 14 to 24. The films on women debunk the claim that women's empowerment in the Middle East is a "wished for" theoretical construct.

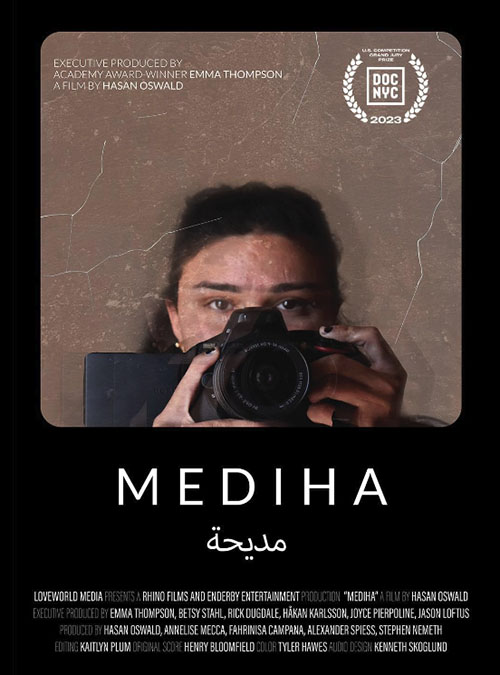

The very real, visualized lives of women feature in three new films about and from the Middle East in London’s Human Rights Film Festival this year. In the documentary Mediha, director Hasan Oswald charts the remarkable personal journey of a Yazidi teenage girl rescued from ISIS enslavement and brought back to life. The feature film Inshallah a Boy, directed by Amjad Al Rasheed, tells the story of a seemingly ordinary Jordanian middle class woman battling against patriarchal and religious inheritance laws that threaten to take away her daughter and their home. Last of the three is A Revolution on Canvas, described as an “art-heist-thriller,” which investigates the whereabouts of 100 missing paintings by Iranian artist Nicky Nodjoumi. In 1980, after the paintings were exhibited in Tehran, they were attacked and deemed “treacherous.” In this family-fuelled documentary by Nicky Nodjoumi’s daughter Sara and her husband Till Schauder, important parallels are drawn between the 1979 protests, which overthrew the Shah, and today’s “Woman Life Freedom” movement.

Each of these films demonstrate that women’s empowerment in the Middle East is no longer a “wished for” theoretical construct. It has become embedded in documented lives and the popular stories that filmmakers insist on telling audiences inside and outside the region — stories that people want to hear.

Who owns history?

From sweeping drone footage of fields of wild tulips and roaming sheep in the panoramic wilderness of Iraqi Kurdistan to the claustrophobic, hidden camera methods put to use in Al Hol, a Syrian refugee camp and ISIS stronghold still home to enslaved Yazidis, a range of camera techniques are employed in the documentary Mediha. The most moving is the shaky, hand-held footage shot by 14-year old Mediha, as she wanders the remote countryside outside the Yazidi camp in Iraqi Kurdistan where she lives. Although her conservative community tells Mediha not to speak about her four-year captivity as an ISIS slave, which began when she was ten years old, she takes the opportunity of her solitude and the camera to pour her heart out.

The decision to give Mediha the camera was an experiment by filmmaker Hasan Oswald that would change the course and nature of his documentary. He had gone to Iraqi Kurdistan to shoot a film about the Yazidi genocide and some 3,000 people still held in ISIS captivity, through what he describes as “a classic documentary lens.” However, a photo workshop conducted by producer Annalies Mecca with rescued women and girls, caught the attention of a young boy who lingered to ask questions. He had served as a Caliphate soldier with his brother before the two of them had been freed. The filmmakers, intrigued, went to his family’s camper van and in the corner Oswald noticed a smiling, shy, young girl.

Oswald continues the story on a Zoom call from where he resides in New York City, “There are unfortunately hundreds of these girls in the camp, and in my four years on and off going there, they’re not like Mediha — something shone through her. She had that spark. From day one, she showed the most interest in the filming and the camera.”

The footage she shot of herself “speaking eloquently and beautifully about something she had never spoken about before,” convinced Oswald. “We just right away knew that Mediha was going to have the reins of this story.”

A highly experienced documentary maker, he has worked on numerous current affairs films. His debut documentary High Love won an award. Mediha is only his second independent film, yet he was already thinking about upsetting “the power dynamic between film director and film participant. You know, it’s always been forever unfairly in the balance of director and filmmaker; we do whatever we want. So I set out with the idea of experimenting with handing the participants the camera.”

Other archival footage in the documentary continues this exploration of who owns history and which narratives will survive for posterity. Some of the most chilling imagery in Mediha is archival smartphone footage, recorded by ISIS fighters, showing themselves and their comrades joking to camera at slave markets. Oswald had been working with another of Mediha’s documentary producers, Alexander Speiss, on the 2017 National Geographic film, Hell on Earth: the Fall of Syria and the Rise of ISIS, when he first encountered this material.

“So unfortunately — well, fortunately, I guess, for filmmakers,” the significance is not lost on Oswald: “[ISIS] recorded nonstop as a form of propaganda. There are troves and troves and troves of archival footage, [about] what they did.”

This contrasts sharply with the dearth of visual material on Mediha’s family. When ISIS attacked the Yazidi villages they burned “pretty much everything,” observes the documentary maker. As Mediha and her brothers confirm in the film, not even a photograph of their mother survives.

The director continues, “We were lucky to get that one wedding tape from the family. So Yazidi archival imagery is limited while the ISIS archive is in abundance.”

The shy, young bride that is Mediha’s mother, Afaf, stares out of the wedding video. Her face haunts the rest of the documentary. To this day, she is still held by ISIS, and doesn’t know whether her children survived the attack. Through a network of Yazidi rescuers Oswald hears that Afaf might be in Al Hol refugee camp. He goes across the border to Syria in hopes of finding her.

Oswald and the Yazidi woman rescuer, Dr. Nemam, who takes him there soon learn from an informant inside the camp that Afaf had moved. She has a new name and the children she had given birth to — since her enslavement — make it all the more difficult for her to return to her community. These children, unrecognized by the Iraqi state, would be treated as outcasts. Many enslaved Yazidi women won’t or can’t abandon their children to ISIS control in the camps. This story also sheds light on the tragic situation of Shamima Begum, who lost her British nationality. She and her children have been prevented from returning to the UK and remain in a Syrian refugee camp.

For those female Yazidi victims raped by ISIS, a fatwa had to be issued by religious authorities to allow them to return to their communities. The Yazidis are “a conservative ethno-religious culture,” explains Oswald, “but to their credit, that shift had started, and we sort of saw it with Mediha. There was no hesitancy from [her guardian] Uncle Omar about letting her work on this film.” While her two brothers, too, are told not to talk about their experiences, in the documentary it is obvious they are allowed more freedom. For example, they can go swimming, while the girls and women are stuck at home with the demons of their abduction and sexual abuse raging inside their heads.

It is this future that Mediha fights against. In the film she often alludes to her own struggles with depression and anxiety. Interestingly a breakthrough comes at a genocide clinic. After reviewing hundreds of photographs of ISIS fighters she is finally able to identify her captor. Only then will the authorities prosecute him; that is, if they can find him. Whether the prosecution actually happens or not, the expression of spotting him and the sense of some sort of closure on the teenage girl’s face are unmistakable. However, there are relatively few happy endings in a story like this one.

This knowing documentary also takes us behind the trophy news footage of another Yazidi saved from ISIS. The group had kidnapped Mediha’s littlest brother when he was still a toddler. Now five or six, he is returned to Uncle Omar from the ISIS family who had been raising him in Turkey. In the evening of the first night back, after all the excitement of returning to “his people,” the little boy has a meltdown of catastrophic proportions. He sobs for his mother, not Afaf whom he doesn’t remember, but the woman who usually slept with him and kissed him until he fell asleep. Only big sister Mediha speaks the language he now knows — Turkish. The strangeness, mistrust and fear are something each and every one of the kids in this family experienced upon their return. They were coming back not to the home they once knew, that is a Yazidi village, now abandoned. They were returning to a camper van that belonged to their uncle.

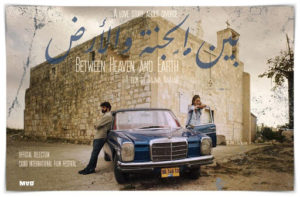

Hard to imagine that a spouse so attuned to married life has a secret existence that unravels after death. Although there were clues. In the opening scene of Inshallah a Boy, female protagonist Nawal, played by Mouna Hawa, prods her obviously tired husband. They need a repeat performance of the night before if they want to take advantage of her optimum fertility in her monthly cycle and try for a baby. After he dies that night in his sleep, Nawal learns that her husband had left his job months ago without telling her. A mysterious caller keeps ringing his mobile, which by Jordanian law she is not allowed to unlock because she’s not the phone’s owner. Also unknown to her was that her husband had fallen behind on his payments to his brother for the money he had borrowed for his pickup truck.

Worse still, is his neglect to sign official documents. These would have proven that the proceeds from the sale of Nawal’s gold jewelry and her wages from working as a care provider in an upper crust Amman household had gone towards the purchase of their home. More than any extramarital affairs he might have had, this oversight means her in-laws can legally sell Nawal’s apartment out from under her. Furthermore, they could claim a significant portion that could leave her and her daughter homeless. If she remarries, they have the legal right to take over the guardianship of her little girl.

Who owns women’s bodies?

Inshallah a Boy is compelling social realism. First time feature director Amjad Al Rasheed is in France where the film has been premiering. He tells me, again over Zoom, that a close relative of his had been in a situation similar to Inshallah’s character Nawal. “At that moment, many questions crossed my mind. Is it possible for a woman to say ‘no’ in Arab society — ‘no’ to all these rules and traditions? What are her options; what would she do? From this came the story for Inshallah a Boy.”

Although his film is firmly rooted in Jordanian society and filmed in Amman’s both monied and scruffy working-class neighborhoods, Al Rasheed soon found that the story resonated with non-Arabs.He first realized this when he went to find financing for the film in Europe and the Arab world. After the film was screened in Europe, female audience members came up to him and said that the situation for women was different in respective countries but the hardships they faced were the same.

“That was my intention,” nods the filmmaker. “Not to say this religion or society is bad, but that we are all in the same place. I believe that if there’s a woman still struggling in one country, none of the women are free yet.”

What? Is he saying he’s a feminist?

He answers with a smile, “I hope so. In our modern societies, a man who is not a feminist is a man living in the Middle Ages.”

Inshallah a Boy is a tense film filled with surprises. The story also depicts both the social inequality and individual women’s varying expectation of power over their own lives. These differences become clear in the privileged Christian household where the Muslim working class Nawal cares for the family’s grandmother, a matriarch struck speechless by Alzheimer’s. The woman’s granddaughter, Lauren, played by Yumna Marwan, is dissatisfied in her marriage to a man who plays around. She feels bereft; trapped in a loveless and unstable marriage, she is now pregnant.

Nawal too is becoming increasingly desperate. Being pregnant is the only thing that will hold off court proceedings that will award her rightful inheritance to her in-laws. If she were pregnant, with a boy, then she, her daughter and their home would be saved because the male child would inherit his father’s property and possessions.

The trouble is that Nawal doesn’t know if she is in fact pregnant. Lauren agrees to take a pregnancy test under Nawal’s name, the results of which Nawal can give to the court. But Lauren will only do it if, afterwards, Nawal will help her get an abortion.

Ghadeer Ahmed’s “Abortion Tale: On Our Ground,” published in the The Markaz Review, describes the dangers women face in seeking illegal abortions in Egypt. The same is true for other countries in the Middle East. How did people react, I asked Al Rasheed, when he told them Inshallah a Boy was going to include a scene at an illegal abortion clinic?

He laughs, “I didn’t tell anyone.” For him and his cowriter, Rula Nasser, abortion was the natural progression of the story. He points out that when the film was still in development, he did much of his research, earning a living by making corporate videos for NGOs in Jordan. It was then he “met women from different social strata and religions, and they are all fighters and strong women. Most of the problems in their lives come from a man in their lives. They all feel they are the weakest link in society. That’s why I insisted on showing different classes and religions in the film.

“For Nawal’s character specifically I didn’t want to portray her as a victim. She is a victim [because of the circumstances against her] but she’s not acting like a victim.” He contrasted her character with Lauren’s. Lauren was like those young women the filmmaker knew in Amman who had studied abroad and thought they were above the social pressures women like Nawal faces. However, the last time we see Lauren in the film, she has been utterly destroyed by the abortion. Her mother is so mad at Nawal for accompanying Lauren to the abortionist’s that she loses her job and ends up in a more precarious situation.

Inshallah a Boy received funding from the Jordanian Royal Film Commission, which also supported Tina Shomali’s AlRawabi School for Girls, the Netflix series now in its second season. Between Inshallah’s abortion scene and themes of self-harm and social media trolling in Rawabi Girls, the Film Fund doesn’t shy away from modern issues. And Al Rasheed adds, neither do modern audiences. At the premier of Inshallah a Boy at the Red Sea Film Festival in Saudi Arabia, audiences clapped and hooted as they recognized the issues in their lives that Al Rasheed’s debut film depicts.

Where are the paintings?

The artist Nicky Nodjoumi met his wife-to-be Nahid Hagigat when they were both art students in Tehran. The two of them went to study in the U.S., and became involved, particularly Nodjoumi, with the anti-Vietnam war movement. When people took to the streets against the Shah, he left his wife and little daughter, Sara, in the States, returned to Tehran and took an active role in the protests. In 1979, the leftists, communists, and secular men and women were indispensable in the Iranian revolution that overthrew the Shah. Ayatollah Khomeini had promised that the Iranian people had nothing to fear from a religious government, and that women wouldn’t lose their rights. However, once the Shah fled the country, the intimidations, killings and imprisonments began; women lost all their rights.

In 1980, an exhibition of 100 of Nodjoumi’s paintings, Report on the Revolution, opened at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. Highly allegorical imagery has been the mainstay of Nodjoumi’s work until today; but on this occasion it so offended the Islamists that they stormed the museum and shut down the exhibition. Nodjoumi had been arrested and threatened before. He fled the country after a voice over the phone told him his life was in danger.

A Revolution on Canvas documents the furor around the exhibition and the sudden disappearance of the allegedly “controversial” paintings. Ostensibly there was not much to go on — newspaper clippings, the memory of Nodjoumi, now in his eighties, and recollections of a few friends and sources in Tehran, their identities, faces and voices disguised in the film. Even so, through careful research the filmmakers uncover a trail that leads friends of the artist to the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art’s basement, where there exists a treasure trove of lost work — considered “degenerate” by the regime. Among the Andy Warhol Mao silkscreens are Nodjoumi’s missing paintings.

But that is only part of the story in the documentary, the second film directed by Nodjoumi’s daughter Sara, with her husband Till Schauder. Another disturbing aspect in the film is how Nicky Nodjoumi’s life and art have been formed by the lengthening shadow of political events in his country, the ramifications of a life in exile and the pressures on his family.

In 1980, Sara Nodjoumi was seven. Ronald Reagan had just become president. As she says in a press release, “My father returned from a ‘revolution’ in Iran that he had set out to document in his paintings. I was hearing words like ‘prison,’ ‘lashes,’ ‘escape,’ ‘survival.’ I heard about an ‘exhibition’ that was vandalized, a ‘damning newspaper article,’ and the need to escape the country. I remember my mother making frantic phone calls to influential Americans that she hardly knew, begging for a visa so my father could get out of Iran. It seemed like his life came to a grinding halt and I didn’t understand why.”

Nicky Nodjoumi is considered one of the most important Iranian artists of his generation. In many ways, in meaning but not execution, he carries on the visually sardonic critique of power as reflected in the iconic ink pen drawings of Ardeshir Mohassess (1938 –2008). Nodjoumi’s large colorful paintings showing naked women in partial chadors, men in suits donning animal masks and the reoccurring figure of the Harlequin explore the raw ambition and corrupting nature of power. At times A Revolution on Canvas is the equivalent of a very intimate artist’s studio visit. Nodjoumi maps out a grid on large canvases and starts painting.

Like all immigrant families he and his wife Nahid Hagigat, an artist in her own right, struggled to make a living. Eventually she gave up art to support her family (she returned to painting in the ’90s). The tensions in the marriage were too great and eventually the two separated. Tears can be telling; both Hagigat and her daughter Sara cry in the film over this fraught and complex family history. For Nodjoumi, the tragedy remains the people and the country he left behind. His expression fills with an emotion akin to tears as he and Sara sit together in front of a computer screen and look at a formal family portrait of the Nodjoumis taken in Kermanshah, when the artist was a teenager. Everyone is wearing their best clothing in what appears to be a photograph taken by a studio photographer. This was taken before the Kodak Instamatic reached Iran.

Nodjoumi points to each of his brothers and sisters and tells their stories, about an unexpected death or tragic addiction. His parents are there too, staring at the camera, frozen in time.

From political Tehran recreated in an artist’s studio in Brooklyn, to Amman and Iraqi Kurdistan, the films about and from the Middle East in the 2024 Human Rights Watch film festival reveal facets of experience that will shock, gratify and touch even the most hardened of audiences. And that includes many who think they already know the region.