Sunset in Amman, Jordan (photo Getty Images).

In which the American daughter of a Jordanian professor remembers life and wasta in the old country.

C.S. Layla

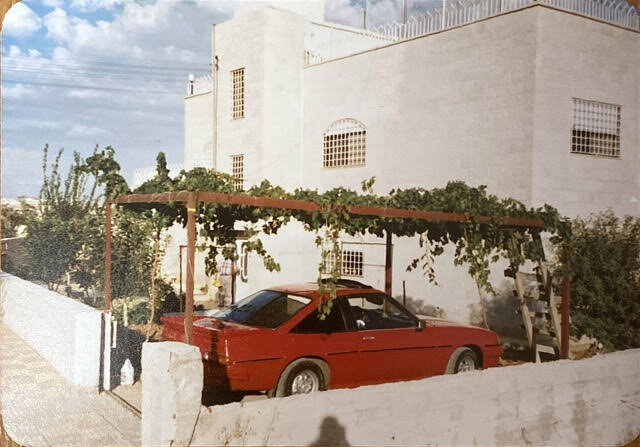

We are on the way to my favorite place in the world, careening along in Baba’s blood red two-door converted racing car. It’s an Opel Manta from 1983 with a black sunroof, its current iteration an honorable evolution from its previous bright yellow and black stripes, which had lent it the look of a floored bumble bee and which Baba hadn’t minded when he bought it because he is color blind. The air is dry and gritty in Amman and I can taste the sand on my tongue. Another car cuts Baba off and he curses so mellifluously that I’m bursting with admiration.

The Opel used to have AC, along with heating and a radio, but when Baba left the car in his village and went to visit America, it got stripped of those luxuries and we never replaced them. Baba claims this used to be one of King Hussein’s cars, which is plausible because the King is an avid collector, but my mom never can confirm if this is actually true. As I remember it, gas is still leaded and smog hovers around the palm trees.

Although we are in a big city, goats leave droppings in their wake along the side of the road, stopping traffic for shits and giggles. I’m wearing my favorite all-purple ensemble, featuring a skirt layered over tights and a long-sleeved sweater with fuzzy flying bears. Baba is dressed in smart casual and thick black sunglasses, his hennaed hair combed back and gleaming, his mustache bristling with importance. The pocket of his shirt holds a red pen constantly at the ready for grading his students’ black and blue university papers.

He is in a good mood, whistling cheerfully on the way to the mana’eesh shop in Bayader Wadi Al-Seer. Baba never has free time and this trip will thrillingly lead to impossibly hot ovens (that I can’t remember the name of) which turn cheese, meat, spinach and zaatar pastries into bubbling pies of perfection. My favorite is the salty white cheese boat with small black nigella seeds dotting its surface. This is the stuff of heavens and once we leave Jordan, I will think about them obsessively; the craving will never be satisfied.

Baba’s Opel Manta.

Workers routinely line the street waiting for their lunch, jostling and chatting with a cigarette in one hand and a piping hot miniature black Alghazaleen Ceylon tea in the other, ensconced in a glass containing just as much white sugar as actual tea. Or, maybe a qahwa made by boiling down coffee repeatedly and adding cardamom and even saffron if you’re feeling fancy (but not in this case because it’s coming from little vendors on the roadside).

Baba and I struggle to communicate, with 50 years and a gender between us, but food is our common language. We both have potbellies, although my version is dubbed baby fat. We are wearing seat belts, unlike the majority of others on the road, but I glance down uneasily at the car floor, which my mom jokes is so rickety and low to the ground that you can see the road passing by underneath. I am too young to understand sarcasm, so I clutch my seat for reassurance. Baba takes impeccable care of this car and each one that will follow it, but he is also capable of driving a piece of machinery until the work he is doing to keep it running is disproportionate to the work it is doing to get him places. Riding the delicate balance of elderly car care is his expertise.

Baba’s driving is wild by American standards and tame by Jordanian. In actuality, my American mom has more fun on the haphazard Jordanian roads, whose names frequently change depending on who’s on the throne and usually don’t bother with updated signage anyway. All of this is irrelevant to her because she has not mastered the art of reading Arabic.

“Mom, how do you not get confused?”

“Are you kidding? I love driving here, it’s like a real-life video game,” she grins.

On the way to the shop, Baba and I are pulled over by a cop for some reason, which is surprising because stop signs and other attempts at traffic control are usually mere suggestions. The cop is young and in full military gear, with a machine gun slung over his shoulder (which may or may not have been common at the time) and a jaunty cap.

“Assalamu alaikum.”

“Alaikum assalam.”

He and Baba begin their assessment, bestowing peace on one another, greeting and singing, parrying and teasing. When he hears Baba’s name he exclaims, “A [REDACTED]? A Doktore?! Doktore [REDACTED]?!?”

A thousand illustrious thanks to God and apologies are exchanged, future generations blessed, carpets of roses thrown. They are in their element, playing out a script as old as time. The cop quickly waves us on our merry way with a “ma assalameh,” one final olive branch, and Baba coaxes the car into gear looking like a cat who swallowed a canary. Our tribe is prominent in Jordan, and at that time a member was a general in the army, so our name recognition is at its peak. This is called wasta.

* * *

Raised in the desert by a Bedouin woman, Baba was unaware she wasn’t his mother until he was around six years old. We aren’t sure of the year he was born, so ages and dates are approximate. Once he learned the truth, he was returned to his birth parents, who had been unable to care for him previously. Their family was semi-nomadic by this time, beginning to be pinned down by borders, and often settled in Roman ruins that dotted the desert landscape. Baba never truly felt that he belonged, and his search for answers began early in the form of a drive for completing his education. His father had been a successful trader but was forced to turn to agriculture with the creation of Israel and was met with a difficult profession and poverty. Baba always said his earliest memory of his own Baba was lighting his now useless Palestinian currency on fire.

Through a series of logistical acrobatics involving, as he tells it, a lot of desert trekking, donkey rides, mocking hyenas, squatting in abandoned buildings, and helpful nuns, Baba progressed in his schooling until he was given a scholarship to attend the American University in Beirut for his bachelor’s and master’s and eventually a PhD in the United States. In return, he would pay off the debt by working in civil service in Jordan.

Between degrees he had a myriad of jobs including working at the brand-new Jordanian radio and TV stations, for the UN, at the airport, and in customs. As he gained experience, he somehow adopted the kind of American accent which can’t be pinpointed to any particular region, and at the same time became immersed in the pan-Arab movement, hoping for a freer and more egalitarian society, which is generally the opposite of what the States had planned for the region. At first, he imagined a modernizing movement, but over time as he hit one dead end after another in his home country, he felt unable to make a difference.

As a professor at a Jordanian university, there came the opportunity to co-author a book with an American professor, explaining the history of wasta and highlighting the extent of its hold and subsequent corruption. Baba believed it would broadly be about its function in the Middle East, not the detailed indictment of corruption in every facet of Jordanian society that it came to be. This would result in many trials, perhaps most memorably the appearance of a dead cat in his office. For these reasons and many more, all copies of the book disappeared from our house.

Before the book had disappeared and the first time I noticed it as a kid, I don’t remember how old I was, but I do remember that the hardcover was an aggressive red, like Baba’s old race car. The title is [REDACTED]. His name is in black along with a co-author and the dedication reads: “To six women who know and love the Middle East, or who will grow to do so,” then my mother’s name, my own, and four others in the co-author’s family. The copyright is from when I was a year old. Although I am already an avid reader, the book looks boring to my child-eyes and I snap it shut.

In 2012, I returned to the old country for the first time since we left. Right away, my surname was recognized. I felt panicked, knowing I couldn’t live up to the wasta potential and could never fill Baba’s shoes, for factors that were out of my control, like being a woman.

In the language study program I joined in Jordan, several of my American colleagues knew about Baba’s book and had referenced it in their work, making me feel foolish for not having read it.

In Jordan, I took on the mission of renewing my passport, which intimidated me because of the intricacies of the language and the male-dominated offices. Ironically, I achieved what would have been a drawn-out process quickly thanks to the help of a friend of a friend who was a wily, likable lawyer. Balding and in a grey suit with a Marlboro packet sticking out of the breast pocket, he convinced the official that he was in fact my cousin and could serve as witness to my identity. It wasn’t clear to me why he needed to be my cousin to achieve this, but I didn’t ask any questions. When I returned to the language center where I was studying, passport triumphantly in hand, I was ashamed by my bravado when the passport-less Palestinian professor and I made eye contact. In this way, I re-established my Jordanian identity through my own murky wasta.

Our tribe is large and prominent in Jordan. The fact that in between my first and last name on my Jordanian passport is the name of my father, his father, and his grandfather hints at the importance of the patriarchal line in Arab culture. In addition, Baba’s status as a professor elevated his wasta to near mythical status in my child-eyes. His book details that “each of these domains [obtaining a job, importation of goods, passports and licenses…] is covered by formal rules, but wasta involvement expands the range of possible outcomes.”

I love “expands the range of possible outcomes.“ This reminds me of Palestinian-American author Zaina A

rafat’s You Exist Too Much, where she writes that “…every price, role and border can and must be negotiated.” Existence in these climates, along with the rules that govern it, is elastic.

My mom wanted a copy of Baba’s book for posterity, and because it’s out of print, she paid a handsome sum to have one shipped. She never took it out of the box until I realized she had it and asked, and then she smuggled it over to me like we were making a drug deal so that Baba wouldn’t see it.

For some reason, the cover on this edition is pure white; it is angelic, innocent, the aggression of the red replaced completely, although the bold black title stands out even more now. I can’t ever recall seeing another pure white book cover, and this one has never been opened. In corona quarantine, I thumb through it, wondering if my love for the Middle East has grown to suit the dedication.

On the first page I read: “wasata, or wasta, means the middle, and is associated with the verb yatawassat, to steer conflicting parties toward a middle point, or compromise.” I realize that to my blond, blue-eyed mother and myself, the only child their union produced, Baba was literally our middleman to the world outside our small fourth-floor apartment, underlining my hyphenated existence. In Jordanian society, my mother and I were both oddities, and Baba was our identity capital.

In English, wasta is loosely translated as nepotism, and I learned that this comes from the Latin root for nephew, which is nephos. What would the word be if the Latin root for niece were used instead, which is nepti? Neptism? Would such a system even exist in a matriarchy? Or how about in a world that moves away from the gender binary; what power structure would be created then?

When Baba’s book was published, the authors believed that “the modern wasta is more of a politician than a tribal chief, in that he is perceived not to honor his word all the time.” They felt that wasta had shifted from a helpful form of tribal negotiation to entrenched nepotism and corruption brought on by urbanization and centralization, and that it should be mitigated. These observations came even before the escalating upheaval the Middle East faced throughout the subsequent decades. Reading this work is heartbreaking when seen through that lens, in how many unknowable disasters awaited the region and in how completely Baba’s idealistic vision of the future of his country would be lost.

My mother clearly remembers sitting in another lovingly used ancient clunker in the driveway of their log cabin, where Baba told her that they had wanted to publish the stories with different names, alluding to rather than pointing fingers, but the publisher wouldn’t go for it.

“Why would he have risked publishing this?” I asked her.

“As he became more educated, traveled outside of his developing nation and gained more life experience, he felt that the only way to improve his country was through tough love, by shining a light on the truth of his experiences and advocating for transparency,” she warily replied.

In that car he told her, “You know, this will ruin me.” And in many ways, it has. When he hit 60 and got his pension, he left the university and his country and never went back. Although he still regularly introduces himself as being from Jordan, Baba hasn’t returned in 16 years.

The thing about wasta is that it’s location-based. In the American Bible-belt, Baba’s name recognition disappeared. Worse, my parents hadn’t applied for his American citizenship until after 9/11. My memories shift from him standing in his power to him standing in line at Trader Joe’s (a very big deal when it first opened up here). He’s waiting for a sample of who-knows-what because there is nothing Arabs love more than tasting food before buying, which they do by plucking fruit freely from stalls in the Middle East but which is not socially condoned here unless it comes in the form of tiny plastic cups.

Baba makes it to the counter, with a thousand fruits and veggies in his cart, and the employee looks him over. “Where are you from?”

“Jordan,” Baba brightly responds.

“Well, we don’t serve your kind over here.”

When I hear about it later, I’m furious not only that it happened but also that the racist, xenophobic white guy chose such a cliché response. My trauma-ridden Baba didn’t make a scene because at the time he still wasn’t a citizen. How do you weigh who belongs in which space? This is something I ask myself every day.

Although Baba no longer has his tribe to draw on, as my mom always says, “you can take a man out of the desert, but you can’t take the desert out of the man.” He still knows a guy who knows a guy, which came in handy in 2016 when the back door of my parent’s van was bashed in and they enlisted a local Arab to fish through the scrap heap until he found an exact replacement. My mom then gave an air conditioner to a white guy with a Southern drawl in exchange for hauling the old door away.

Much of Baba’s book is based on personal experiences, because “wasta is a complicated, paradoxical concept that is better described by stories than circumscribed by an arbitrary definition.” These numbers seem to perfectly encapsulate the nature of the issue in this reference to “a 2000 survey among Jordanians. Eighty-six percent agreed that it is a form of corruption and 87% thought it should be eliminated. At the same time, though, 90% said they expected to use wasta at least ‘sometimes’ in the future and 42% thought their need for it was likely to increase, while only 13% thought their need would decrease.”

My trip to Jordan in 2012 was nearly 10 years after we had moved away, and now almost another decade has passed, so my own relationship to the country and how wasta functions there is frozen in time. As I read through Baba’s book, I became curious and Googled the word looking for more modern references.

I found a whole host of amazingly bizarre iterations, like the Urban Dictionary definition as “connections and to a lesser extent, street cred,” that a Wasta is also a White Rasta as in a white person imitating aspects of the religion without holding the beliefs, that a subversive board game called Wasta exists in Lebanon, and that this mug is available which says, “don’t use wasta, be the wasta.” According to The Turban Times: The Middle East As You Don’t Know It, wasta is even referred to as “Vitamin W” because of how vital it is to survival.

Fascinatingly, I found a town called Wasta on the Cheyenne River in South Dakota, complete with a Wasta Hotel, currently on the National Register of Historic Places, and a Wasta Post Office. The town’s population was 130 as of 2019 and the name comes from the Lakota word “wašté” meaning “good,” which is just too perfect a juxtaposition.

When my parents decided to purchase a used Toyota Camry from the dealership, Baba haggled the price down so low that they were border-line losing money on the sale. Still, the price wasn’t where he wanted it, and Baba became fixated on getting another $75 off. He settled in the bewildered manager’s office with an awkward mug of tea, transferring the custom across an ocean and continent, parking himself as solidly as the cars around him. Raised poor without any form of transportation save a do

nkey or the occasional camel, Baba knows the true value of both a car and a dollar. Once he got his inevitable bargain my parents and I drove out of the dealership together, leaving the dazed manager behind.

Above all and no matter who he is talking to, Baba is formidable. He will never lose his finely honed negotiation skills, his single-minded determination, or his mustache.

As I reflect on the experience of finally reading Baba’s work, I realize that this formal text has unintentionally had the personal effect of tying me back to his experiences, explaining his life within a system that he felt he failed to change. It even details the history of our tribe, a group which he, and I by proxy, now have no contact with. Baba doesn’t even know I’ve read it.