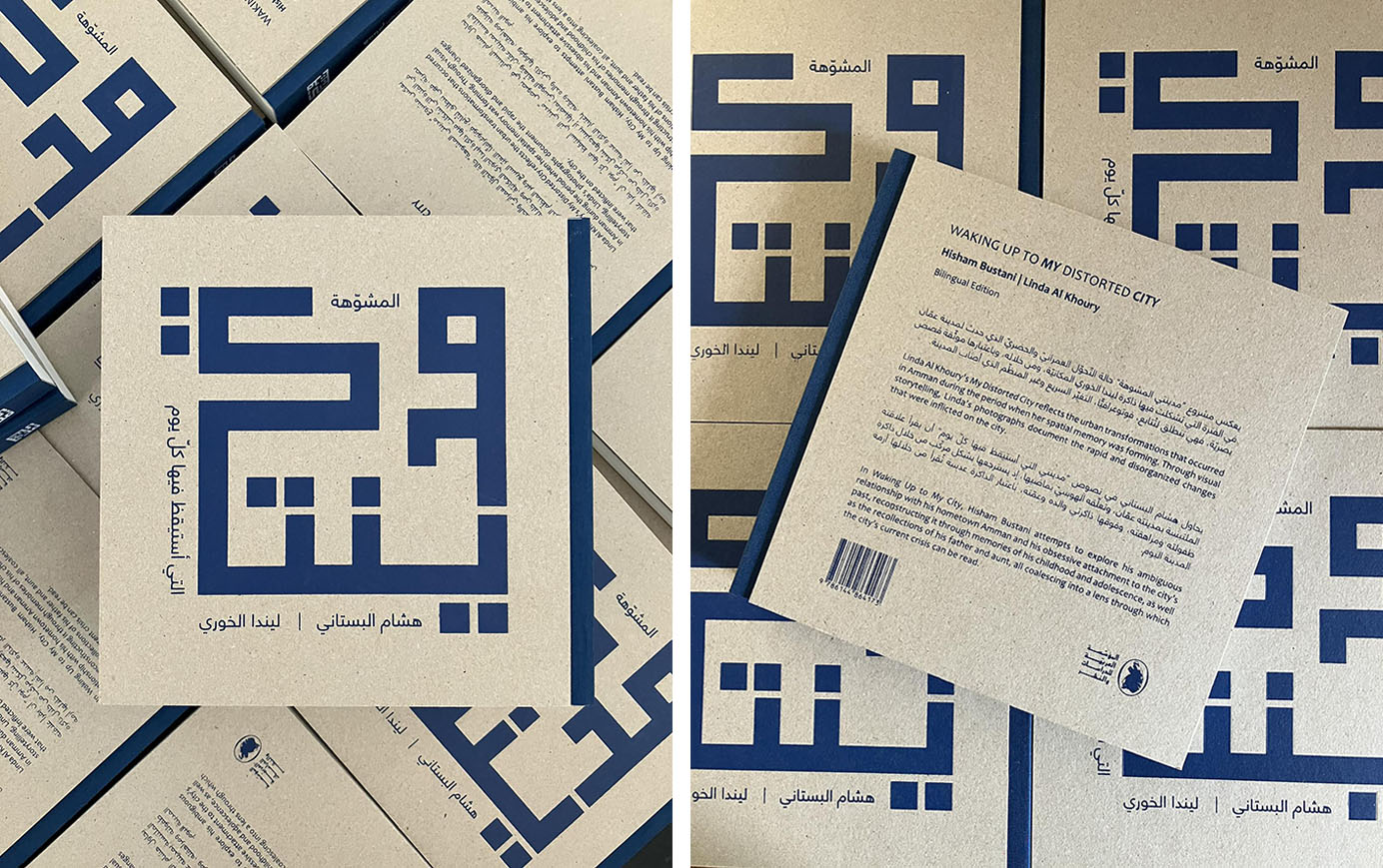

An exclusive excerpt from the new bilingual Arabic-English book “Waking Up to My Distorted City” by Hisham Bustani and Linda Al Khoury on the “urban” distortion of Amman.

‘urbane’ behavior is an issue of structural social production that concerns the very foundations of society. When the authorities monopolize the scope and space of societal organization—interfering with its mechanisms in ways that separate the citizen from the practice of their citizenship, and thus remaining unchallenged as primary actors—then the responsibility runs much deeper than the small part born by the individual.

Hisham Bustani

Translated from the Arabic by Addie Leak

What is “urbane” or “civil” behavior? Is it the opposite, say, of rural/provincial or Bedouin behavior? Is the sexual harassment that accompanies the crowds in cities or quasi-cities “uncivilized,” the opposite of urbane? And can societal deference among villagers be considered a form of civility practiced by “uncivilized” people? The latter conclusion would resemble that of Nahda thinkers in the late 1900s who, dazzled by European “civilizational” achievement, summed up their observations as having found “Islam without Muslims.”

Platitudes and superficial generalizations won’t take us far. Let’s say that “urbane” behavior consists of mutual respect and social solidarity within the population, collective voluntary compliance with the group’s customs and laws, and the understanding that the group’s interests form self-imposed constraints on its members’ actions. All this is more likely to be found in the countryside and desert than in our malformed cities. These cities, in my opinion, are random amalgamations of population groups that are yet to find a collective common ground, and — given the prevailing forms of administration and governance — are unlikely to find it any time soon. More on this later.

It’s worth remembering that when this “city” (Amman) was a “village” — from its genesis as the administrative capital of Transjordan until the 1970s — its ethics were “urbane,” according to the testimonies of those who remember “the good old days.” Back then, its families knew each other on a personal level. East Amman had not yet become the impoverished, semi-isolated “ghetto” it is today, or spilled over into the mixed bag of “upscale” West Amman. The myriad factors behind these variables are beyond the scope of this essay, but once the “village” had grown, exploded, mingled and become a “city,” its inhabitants’ behavior became corrupt and brutal. To compare the “village” era with the “city” era, let me offer as an example a story my father tells about my grandfather, Abu Abdo, who owned a dried-goods shop on King Talal Street, at that time the city’s crowded main thoroughfare. The story goes that whenever my grandfather found a wallet, or anything else of value, that a customer may have lost at his shop, he would simply hang it on the door as a public service announcement, where it would stay until its owner came back to claim it.

Now it’s time to question another platitude: Are ethics and human behavior subjective or objective? My response puts the objective before the subjective, meaning that if we look at Amman from the 1930s to the 1970s, we find a broad, fairly affluent middle class, constituting a social scene that in no way resembles Amman of the ’90s or the transformations that followed the collapse of the dinar and the implementation of IMF recommendations, with their accompanying slow, steady erosion of the middle class. It was then that people shifted from a forward-looking position of comfort to one of intense competition for their daily bread, with a primary focus on the ever-fluctuating present. This shift coincided with the meteoric rise of the nouveau riche — corrupt officials, monopoly-grabbers, the “business” hordes; and owners of major service projects, compradors, and agencies — to the ranks of a dominant minority as the wealthy economic elite, in place of traditional downtown merchants whose traditions had included dealing with Amman as a dwelling space, not as a space for profiteering and violent seizure. Now, the context being what it is, is there a shared urbaneness or civility between 1950s Amman and Amman in this second decade of the new millennium?

A city is a network made up of societal and economic nodes, of buildings, roads, and human relations, set against a backdrop of conventions and tacit agreements, as well as legal, social, and common-law regulatory frameworks. To a large extent, the city itself, with its ingrained traditions and conventions, produces and acts upon the behaviors of its citizens and visitors. For example, if you take an Ammani and put them in London or Dubai, you’ll find that — in no time at all — they’ll start using pedestrian crossings and abiding by traffic laws, and they’ll stop throwing rubbish out of car windows. They’ll use public transport and altogether — quite naturally — adopt what is accepted as “civil” behavior. On the other hand, a “civilized” ajnabi, or foreigner, transplanted into Amman would — in less than a month — start acting like a proper ibn balad, as street-smart as the next local, a phenomenon well known to those who mix with and observe the “civilized” ajaneb scattered throughout Jabal al-Lweibdeh, Jabal Amman and elsewhere.

Societal behavior can then be defined as an objective product of the socioeconomic and political forms that contain it, and of the relationships resulting from the interactions among these, whether positive or negative. The behavior of a society therefore expresses its objective reality, and from the latter we can start to interpret and analyze the former.

Is it enough to have a large number of people gather in one overcrowded spot on Earth to call that spot a city, and to make the prevalent behavior within it “urbane”? Or to begin condemning the “barbaric,” uncivilized ways of this city’s residents and demanding that they transform? Is there such a thing as individual transformation towards urban living and, from there, towards behaving more “urbanely”?

Urban society differs from both rural and desert societies in one fundamental, pivotal way: it’s a society made up of “autonomous,” or “free,” individuals (and here I put the words in quotes because there’s no real freedom or autonomy for anyone within a context of inequality, commodification of basic necessities, and a financial system born of capitalism, the mother of all modern cities). The foundation of urban society is the individual, their desires and tendencies. They’re extracted from the collective to stand naked before those who want to buy their labor, whereas in rural and desert societies, the basis remains one of collectivism, solidarity, and the dissolution of the individual within the group in exchange for socioeconomic protection. In the city, the creed of the individual and their (imagined) freedom is king, as the individual’s existence is entirely self-reliant, and a person’s freedom only stops where that of others begins. But in the countryside and the desert, the basis of society is the common good, and individuals are subsumed within it; where the individual’s very existence depends on their rural or Bedouin community, they cannot exist outside society’s collective codes.

Is this urban “autonomy” achieved in malformed quasi-cities, or within and among the groups that constitute them? Let’s test the theory in two scenarios.

Scenario 1: Personal Freedom — The “City” as a Space for the Group

A young woman walks alone on Rainbow Street at 9 p.m. Or let’s make her walk alone at 9 p.m. almost anywhere in Amman, and maybe at any time of day, morning or evening, too. It’s only “natural” that she should experience multiple forms of sexual harassment: stares from male passersby, comments from male passersby, comments from men in cars, honking from men in cars, men in cars stopping to invite her for a ride, and so on. It’s also “natural” that she should be exposed to disapproving looks or comments from other women accompanied by their husbands or fathers, in response to a comment from said husband or father along the lines of, “For shame! Look what she’s wearing!” or “What’s she doing in the street at this hour?”

This “urbane” behavior leads us to its urban roots: in the “city,” public schools — and many private ones — are not mixed-gender, and their students receive no sexual education to speak of; the children of the city are brought up to see women purely as sexual objects that should be kept out of the public space (which is reserved for men) and isolated within the private spaces (that belong to one man or a small group of men). So the presence of a woman, unattached to a man, in the city’s public space becomes a sexual invitation to transgress; the woman transforms from an individual into a communal object readily accessible to the collective of males. And men, in their turn, take on the role of lechers who choose to respond to this “invitation,” concocted by social convention via the gendered distribution of public and private spaces.

None of this is surprising in authoritarian-patriarchal societies that celebrate a power imbalance favoring masculinity, virility, and male guardianship. Such societies are managed by socioeconomic mechanisms that firmly corroborate this warped situation by portraying it as an authentic standard: the man is the head of the family and the family name and must safeguard them, and the woman is attached to the man and embodies his honor, integrity, and family. In patriarchal logic, a woman who enters a public space unattached to a man is offered up to the males of that space. She must be subjugated, humiliated, and made an example of, because the respectable woman’s place is in the home, not the street. Her place is within the limited boundaries of the domain of one or more males in her life: her father, brother, husband, etc. Such behavior may be surprising in New York or London, where male violation more often takes the form of individual predatory behavior (still linked to the commodification of women as sex objects). But it’s not really surprising in a “city” that fails to truly recognize the individuality of its members and is instead formed of groups that adopt the “vices” of (rural/desert) collectivism and renounce its virtues.

The same perception of women is adopted by those who govern the city. For example: women don’t have the right to pass on citizenship to their children or husbands, and women whose lives are threatened due to so-called “honor” issues are placed in administrative detention, while the men who threaten them are allowed to go free. In the same vein, the Jordan Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities issued instructions in 2014 banning female artists from singing in Ramadan tents, under the pretext of “preserving the sanctity of the month,” meaning that women and women’s bodies and voices (i.e., their physicality) are inherently and purely sexual, inciting lust, making their very presence (according to the authorities) a violation of the “sanctity” of virtue and abstinence during the holy month.

In this scenario, the “city” has become the domain of a specific group—males—while in other scenarios, it may become the domain of any number of other groups. These could include the family (as when families put up celebration tents in the street, commandeering it for their own purposes), groups of vendors (as when Souq al-Juma’a vendors commandeered the old bus lot in Abdali before getting kicked out, or when vendors occupy public pavements downtown) and business groups (for example, when Amrah Park was commandeered to build the disastrous Sixth Circle towers, or in the case of the Abdali “Boulevard,” now declared the “new city center,” none of its businesses having been kicked out by the police or prosecuted by the State Security Court, as happened with Souq al-Juma’a).

Scenario 2: The Limits of Personal Freedom—The City as a Space for One

Policeman: “Move along, no double parking.”

Civilian: “I’ll only be a second — I just want to grab a shawarma wrap!”

Policeman: “All right, but hurry up, or you’re getting a ticket.”

The civilian mock-runs towards the shawarma shop, his car still in the street, disrupting traffic and blocking the exit for several properly parked cars.

We shouldn’t be surprised that this city-dweller behaves as if the city — in its entirety, with its residents and streets — is his own personal property. In it, he can park his car wherever and however he pleases, treating the hazard lights as an all-inclusive free pass. When our citizen finishes his wrap, he’ll open the door and leave the bag of trash on the street — that would be the “respectable” way of doing it, the alternative being to toss it out the car window and allow his children to follow suit. He’ll also let them run wild in the street while he takes over the front yard to entertain his relatives, their raised voices filling the neighborhood late into the night, because the city belongs to him and his children and those that came before him. This citizen will shoot his rifle in the air at his brother’s wedding, as if he were in the wilderness of the desert or countryside, without any concern for the hundreds of fellow citizens’ homes surrounding his own. Any one of them could be at their window, in the path of one of his bullets, and that person could die, but this is an afterthought for our fellow citizen and won’t stop him from celebrating to the fullest. Nor will it stop him from driving a van with a loudspeaker to buy used furniture or sell vegetables or propane cylinders, making a racket everywhere he goes, or from honking the horn of the school bus several times at the “asscrack of dawn” (as they say) to alert students to its presence, jolting sleepers awake every time, or from installing water pumps whose hum keeps the neighbors up at night. The city belongs to him, as we said, and to his father, who also double-parked — and the “understanding” and “empathetic” policeman goes along with it all, because he, too, behaves exactly like his fellow citizen.

We shouldn’t be surprised at a citizen like this because he’s following to a T the example of his city’s officials, who treat the city in a similar fashion, imposing their bad taste on its inhabitants and selling its parks and public squares to any bidder who can afford the privilege of contributing to the overall hideousness. A case in point is what happened with one of Amman’s most distinctive landmarks: its roundabouts. City officials — arbitrarily, certainly — decided that the major addition they wanted to make to their city was the “LED curb,” as if the city’s public spaces were their personal sitting rooms to be decorated according to their own vulgar tastes, in repulsive colors that match nothing but the sponsoring company’s logo, tossing the glowing cubes (or some of them — those that aren’t broken) like so many bags of trash out of a car door and leaving them on the side of the road to be toyed with by the winds of fate. (Because maintenance, of course, is nonexistent. Question: How many water fountains in Amman actually have water?). These cubes will remain under our noses until the poor taste of one politician is replaced by the worse taste of another.

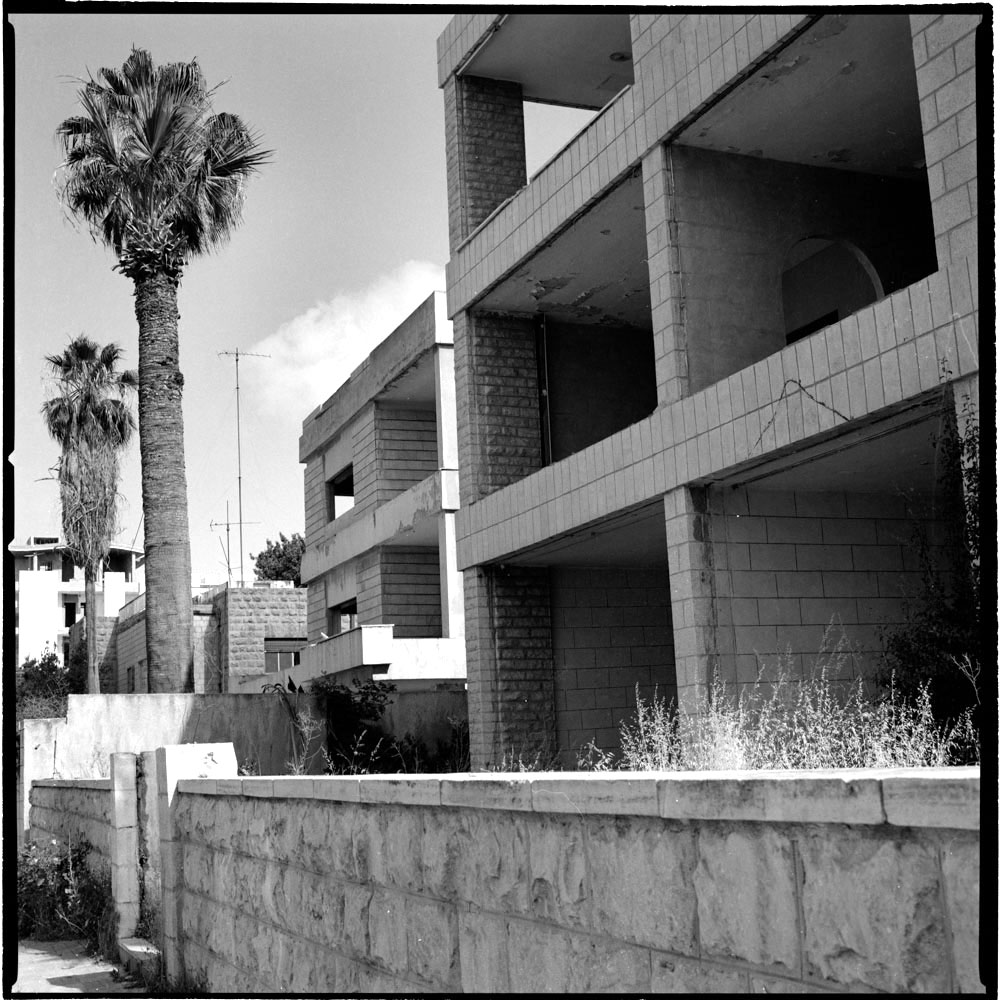

The city’s officials believe they have the right to change the appearance of the squares and spaces, and of the whole city. The old Arab League Café opposite Al-Husseini Mosque was demolished without anyone batting an eye; the glass Housing Bank branch on As-Salt Street downtown, jarring and ugly against its backdrop of old stone buildings, just fell from the sky that way, as did the concrete monstrosity of the Greater Amman Municipality building at the foot of Jabal Amman. The Hashemite Plaza has been changed several times and was finally rebuilt using cheap, shoddy materials unable to withstand weather fluctuations and standard wear and tear. The most recent thing these people bestowed upon us was their permission to demolish an old heritage home near the end of Kulliyat al-Sharia Street in Jabal al-Lweibdeh and to build an ugly hotel on its rubble, as well as their permission to erect a miserable little coffee stand marring the beloved viewpoint over Amman in the same neighborhood.

Visiting London, Paris, or Brussels twenty years ago and then again now, you wouldn’t feel like they had changed on you much. Their main squares are the same, and the old buildings are considered valuable architectural heritage. If they wanted to renovate them, they would gut the interiors and do a full remodel, leaving the old façades intact for future generations of city-dwellers. Buildings have value, as do public property and public space, and the appreciation of this value is contagious and spreads through practice, from the object to the self, as do recklessness and haphazardness when they constitute the common practice. How do you cultivate respect for a “city” that is reborn (or, rather, murdered) about once every ten years? And how can you respect a city that transforms its elegant old street into “Rainbow Street” and its noble old quarter into “Weibdeh”?

When the authority that governs the country and its people owns everything but can neither be investigated nor held accountable (Article 30 of the Jordanian constitution); when city officials act as if the city is their personal domain; when urban society is nothing but a loose gathering of different “groups” or “bands” forbidden from evolving freely within a true civil society; and when the rule of law is insubstantial, non-institutionalized, titular, selective, and unjust, there will be no social conventions or individual freedoms, and no reason to care about either the law or one’s fellow humans.

Waking Up to My Distorted City by Hisham Bustani with photographs by Linda Al Khoury, The Arab Institute for Research and Publishing (Bilingual Edition), 2023. Excerpted by permission from the authors.