Farah Abdessamed

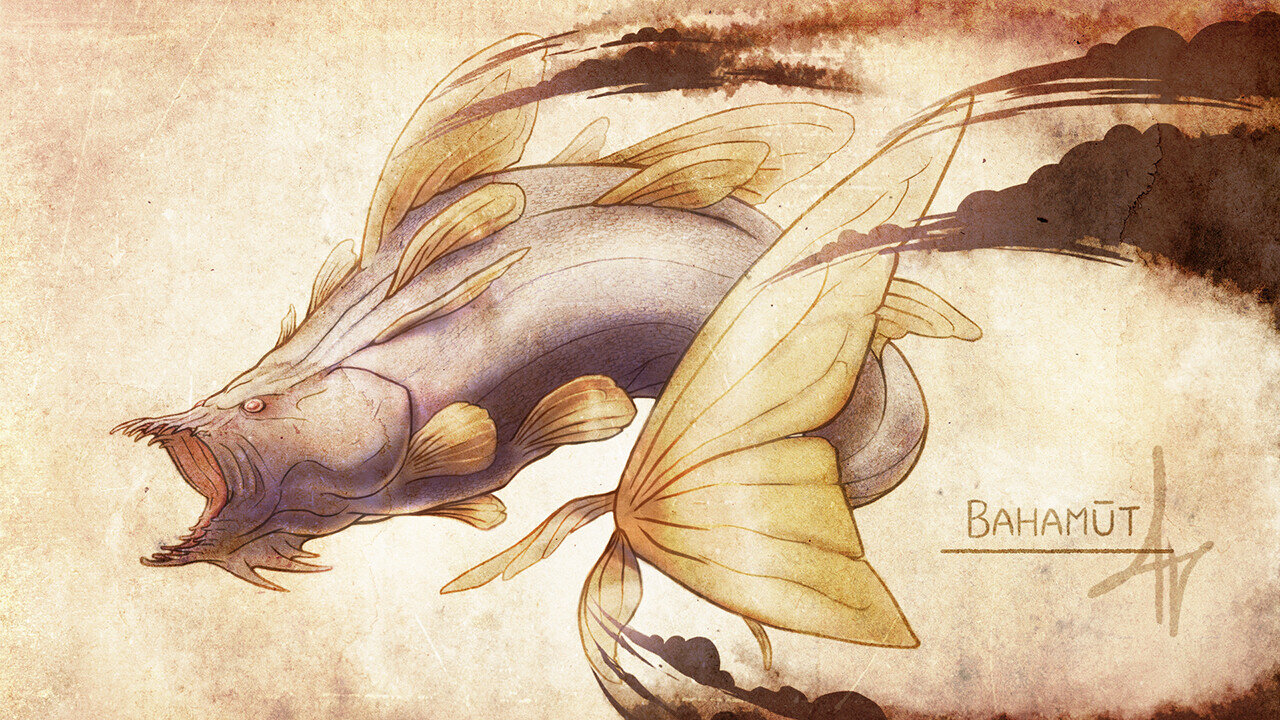

“There was a fish, which carried an ox. And the ox carried a precious slab of stone, which also carried an angel, and guess what? The angel carried the world.” I recall the story and my father’s thrill the first time he tried measuring the size of a big fish with his arms spread out in front of me. The fish is called Bahamut. I was thinking about this monster a lot, along with other sea creatures, looking at the still, eerie and indecipherable forsaken waters of the Dead Sea in Jordan.

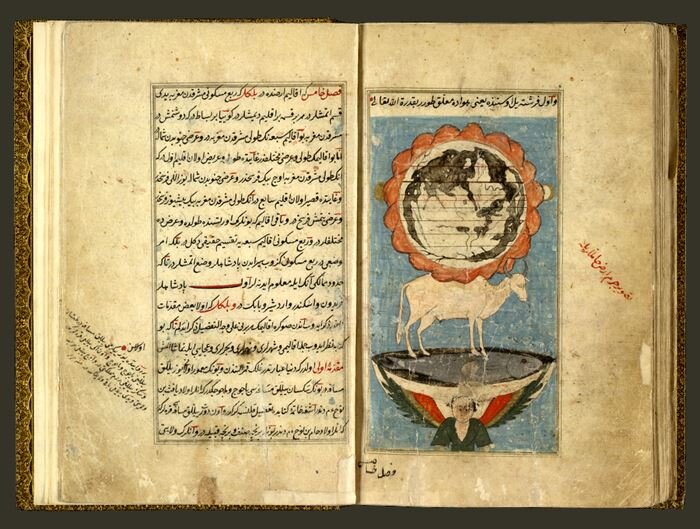

Bahamut is said to be a powerful world-fish creature, a fish or even a whale according to different traditions. It can cause havoc, and chiefly earthquakes. The fish is so big that all “the seas of the world, placed in one of the fish’s nostrils, would be like a mustard seed laid in the desert.” Al Qazwini, an influential scholar from the 13th century CE and author of Wonders of Creation, suggested a modified cosmology to the story my father had told me. At the bottom of his scheme of the universe, an angel holds Bahamut, and at the top the earth or cosmos crowned with the reliefs of Mount Qaf sits on a bull above Bahamut. No matter the sequence and the various layers proposed, Bahamut is a foundation without a base, and this fragile assembly depicts a balance necessary to the stability of the world, from underground (or undersea) to the skies, hell to heaven. “From the moon to the fish,” a Persian saying goes.

Bahamut is said to be a powerful world-fish creature, a fish or even a whale according to different traditions. It can cause havoc, and chiefly earthquakes.

I’ve been lucky to visit the Dead Sea several times, especially when I lived between Amman and Yemen circa 2015-2017. Often, the security situation in Yemen or visa runs required me to stay in Jordan, a country which became a second home during these years. The Dead Sea was a routine ritual. There was always an occasion for it as Amman was an easy hub to meet family, friends and acquaintances. An “accessible” corner of an unruly Middle East. While Yemen was generally bursting with vitality despite hardships, I wasn’t accustomed to a such sight of solitude. Each visit brought greater oddity and unfamiliarity. I’ve concluded in my mind that the Dead Sea is an abnormality, a problem. To understand why, I went back to the past, to myths and recollections.

I’ve always dreaded entering its waters. They awakened a superstition and I became convinced that they held a magical power of some sort. When I was a kid, I usually spent a week or two during the summer holidays by the beach, either in France or Tunisia where my family is from. I grew up with a (justified) fear of jellyfish, shrieking when I felt something I couldn’t see slithering by my legs. I remember seeing tragic jellyfish carcasses littering the beach in late August crepuscular afternoons as both a form of collective suicide, and the irrefutable proof that oceans contain creatures one shouldn’t speak of out loud.

Faced with this infertile mass in Jordan, I had no choice but to consider all the Bahamuts of creation and imagination a possibility. That Arab Bahamut is a likely mash-up of Old Testament figures (a possible mélange of dag gadol, Behemoth and Leviathan) is of secondary importance. It shows that beliefs intertwine, and religions are largely syncretic. “From a hippopotamus or elephant [Arabs] turned it into a fish afloat in a fathomless sea,” writes Jorge Luis Borges. I had no intention of swimming towards a horrific fish-elephant, a fish-hippopotamus, or a fish-anything at all.

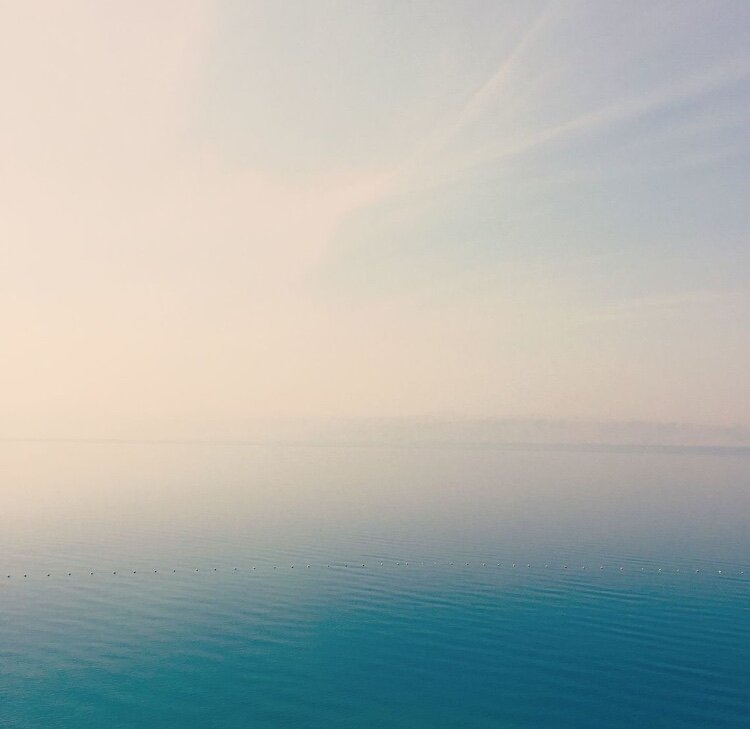

Years before my last visit to the Dead Sea in Spring 2018, reminiscing about sea monsters and coming to terms with its otherworldly features, I faced the trying heat of a July weekend with a friend. There was a languor, a pressure, at the low altitude point below sea level, compounded by the fact that it was very much summer and over 100˚F (above 37˚C). Even though I wasn’t well acquainted with the surroundings (a third visit maybe?), I considered the strangeness of the place. No boats float, and no life survives—save for its imperceptible traces, such as fungi, bacteria and plankton, which must party hard under the slightest and ever-scarce rainfall (less than four inches per year).

“It looks like a coffin,” I said to my friend who entered the Dead Sea. We nicknamed it a “soup” during the hot months. One sweats, even dipped in water. The dried mud on her body dissolved with a few gentle scrubs.

It was so hot; it quickly became unbearable. In mythical Biblical tales, the inhospitable Dead Sea covers the ashes of Sodom and Gomorrah, a story recalled in Genesis. The two cities are told to have perished by divine fire in punishment of their “decadent” ways. The Dead Sea swallowed them. The lake reminded me of a volcanic caldera. It’s surrounded by two mountain ranges, between a formerly disputed border and along a fault line which runs from the Sinai Peninsula to Anatolia. The tectonic soup was a caldron, and we were dishes to be served.

I was always bored at the Dead Sea, so I let my mind wander. What could really survive there, I asked myself, then my friend who looked at me with puzzled eyes. Since my first visit I’d immediately disliked the water’s viscosity, how its density slowly petrified my limbs and movement. Its lack of waves had disorientated me, and forced me to always stay close to shore, sometimes so close that I’d been more comfortable simply kneeling. The corrosive liquid inevitably burned my skin within minutes. I’d felt trapped and attacked, caught in a spider web under a curse.

The oily layer which swims above the water’s surface and clings on to the skin, is asphalt, or bitumen. In Antiquity, the Dead Sea used to be known as the Asphalt Lake. Greek and Roman writers tell us that Ancient Egyptians traded with the Nabateans (a nomadic tribe who founded the desert city of Petra) for its extraction. Bitumen from the Dead Sea was precious and used during the mummification process of dead bodies, mixed with other aromatics. Mark Antony even offered the lake to Queen Cleopatra when his Roman legions captured it from the Nabateans. Despite its sacred use in religious rituals, these ancient sources were mostly shocked by the noxious surroundings:

“I still think that it is the exhalations from the lake that infect the ground and poison the atmosphere about this district, and that this is the reason that crops and fruits decay, since both soil and climate are deleterious.”— Tacitus, Histories, Book V.

Hardly inviting and, unlike our days and the presence of luxury spas, not a place that would rival Roman baths.

Geographically, the River Jordan is the Dead Sea’s tributary. The River Jordan is surrounded by a lush valley and is the legendary site of Jesus’ baptism. It is located northwest of today’s Madaba, close to the Allenby Bridge. It gives (spiritual) life, and nourishes. By contrast, the two places couldn’t be more different though the River Jordan is now a shadow of its former self, modest and brackish. Yet the distinction led many observers through history to view the Dead Sea’s sterility as both a sinister omen, since life dies upon reaching it, and an oxymoron.

During my last visit to the Dead Sea, I drove from Amman passing by roadside shops selling various inflatable ducks and swans I had never seen anyone buying nor using. The road down below sea-level made my ears pop, as we descended 4,000 feet in 30 mins (a short commute by most standards). I spotted the northern tip of the lake first, its deepest point among the largest body of water in water-stressed Jordan. Hidden behind mountains: Jerusalem.

The lake’s surface has shrunk by a third since the 1970s, lost over a fourth of its depth, and continues to recede by an average of three feet per year. One can see markings with various dates engraved by its shores, a token of resignation as the sediments disclose a rapid decline. At a time when global warming causes sea levels to rise elsewhere, the Dead Sea is disappearing before our eyes, in a fate shared with the Aral Sea and Lake Chad. This is due to significant diversions from the Jordan and Yarmouk Rivers, to irrigate agricultural lands, and as a result of overexploiting its salt, and, ironically, potash (a fertilizer).

That day, I reached the lake by late afternoon. Sunset gave way to a gaseous vista. Colors and thick fog blended in mysterious tones evoking one of those abstract painted landscapes from Jonathan Speed I’ve come to love. Its western shore turned blurry, more so than usual. Water evaporated against the Martian-like canvas, and the lake sunk, and continued shrinking away. The diffraction reinforced the dissonance of witnessing the death of something already “dead.” It was already a ruin, a no-space, a fleeting concept, a wreck.

French writer Chateaubriand, who had been to the Dead Sea on his way from Paris to Jerusalem, reported that local tribes used to collect small fish. His predecessors even picked up (live) sea snails on its shores. I couldn’t see any, only the regular bitumen slime and sediments of salt crust crystalizing while I took my first walk out of the car to stretch my legs along the pebble-ridden beach. The stones, carrying a lapidary dignity, betrayed that the lake did dry out once, many, many years ago.

The ambitious Dead Sea to Red Sea canal project, a pipeline designed to pump additional water into the Dead Sea and reverse its extinction, hasn’t come to light despite over 15 years of negotiations. It remains tangled in regional dynamics and tensions. Though the modern alchemist experiment may eventually materialize, for the time being, the sinkholes multiply (from 40 in the 1980s to over 4,000 today), presenting an existential threat to a fragile ecosystem, and the Sea sighs relentlessly under longer exhales. Jordan already loses such a quantity of water every year overall, that its loss amounts to satisfying the basic needs of a third of its population.

The Dead Sea (“salt sea” in Hebrew) is famous for containing nearly ten times more salt than regular oceans. Salt, an essential condiment to food taste and preservation, is linked to survival. Men can be good, like the “salt of the earth.” Could they? I doubted that. I had just returned from Yemen, with its air strikes, daily WhatsApp photos of civilian deaths, emaciated children and other abject deprivations. Ahead of nightmares sure to come, I wondered about this loss and an inexorable feeling of emptiness at night when the air finally turned respirable. A feeble moonlight reverberated gently on its dormant surface (“ennui, that incurable convalescence…”).

From moon to fish then, I wondered what a depleted basin would reveal. What would happen once the hypersaline water fully evaporates from its cauldron? “Reality is a creation of our excesses, of our disproportions and derangements,” said E.M. Cioran. It was an archaic hyperreality in my case. Amid a naked seabed, the shambles of damned cities, maybe the fish bones of giant Bahamut, and why not an entrance to a deeper subterranean world, I thought. I remembered that in the Arabian Nights tale, which I had read the first time I visited Tunisia and my father’s homeland, below Bahamut is a sea, and beneath the sea is air. Beneath the air is fire, and beneath the fire is a creature, sea-serpent, called Falak. The mouth of Falak breathes the fires of hell—quite fitting for the caldera-shaped Dead Sea. On Falak rests creation, and below is unknown to men. So what, then? A mirror of futility, or rather, a dizzying scaffolding of infinite regress, where in the end, one needs to carry and be carried for a sense of harmony to sustain.

To conjure the spookiness, I took a pebble and threw it in the water in a muted thump. Though I don’t believe in jinns, I waited for a reply. No wrath came my way, only the deafening silence of a liminal agony. I carried the illusion of befriending ghosts.

One can choose to view the Dead Sea as an anecdotal spa destination to collect insta-worthy photographs. I opted for its sub-nautical realm, as the cosmic ocean of Bahamut and Falak from the stories I cherish. Less transcendentally, I accepted it as the graveyard of our collective carelessness. Behind the veil of desolation, is not a divine disaster, or an essence of creation, but a very human environmental tragedy of decadent scale — entirely avoidable.