To commemorate the Day of the Imprisoned Writer,* we interviewed Kurdish poet İlhan Sami Çomak, who was incarcerated for thirty years.

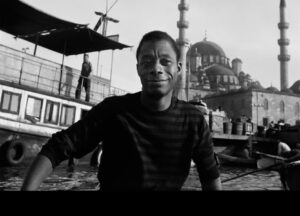

İlhan Sami Çomak is a Kurdish poet who spent thirty years, three months, and eight days in prison in Turkey. Born in Karlıova, Bingöl, in 1973, he was arrested in 1994 while studying geography at Istanbul University and accused of involvement in political activities — a charge he has always denied. Convicted after years of legal irregularities and reports of torture, Çomak went on to become one of the longest-imprisoned poets in the world.

During his decades of incarceration, he wrote tirelessly, publishing numerous poetry collections that reveal a voice both intimate and expansive — rooted in the landscapes of his childhood and the imagined geographies of freedom. His poetry, marked by tenderness, imagination, and an unbroken faith in life, turns to nature and memory as acts of resistance and renewal. From the confines of his cell, Çomak transformed isolation into a profound creative force, establishing himself as one of the most vital and enduring voices in contemporary literature.

My first encounter with Çomak was through his poems, when I was invited by PEN Norway in 2021 to translate some of his work into English, along with poems written for him by acclaimed international poets, who were seeking to raise awareness of his unlawful imprisonment. Our first conversation, however, came much later, after his release in 2024. It remains one of the most unforgettable moments of my life: Çomak, a free man at last, walking down İstiklal Avenue in İstanbul, his voice bright with wonder and joy. That sound — his laughter carried through the crowd — will stay with me always.

This interview was conducted in Turkish through correspondence and translated into English by Sevda Akyüz. We’re publishing it a day before the Day of the Imprisoned Writer 2025.

·

Öykü Tekten: It took me weeks to decide where to begin this conversation. Would it be an exaggeration to say the delay was winter’s fault, that its long shadow held me back? So be it. Like many others, I first came to know you through poetry — not only as a reader, but as a translator too. That feels like the right place to begin: with poetry, and with translation. How did poetry first enter your life? Which poets did you read, who inspired you then, and who continues to inspire you now? Which poems live in your memory by heart? And which books are close at hand these days — on your desk, or perhaps carried in your pocket?

İlhan Sami Çomak: Beginning this interview with poetry — with the warm familiarity it has fostered between us — seems to be a fitting choice. Especially in Istanbul’s lingering cold, the biting rain and wind, it feels like exactly the right place to start.

Wasn’t it poetry, after all, that brought us together, dear Öykü?

We are after you

We are in the time of leaves, in the evening

of sprinkling salt

The whirlpool is expanding on end, troubles multiply

The heat of stones walks from the past to the future

We are in search of smiles infusing light

with the dried fruits and nuts in our pockets

The sky slits open by the crackling sound of branches

Maybe here at our feet

with our steely gaze parsing the marble

with the spirit of a horse going down to the water

we are going after the wind.

Translated by Öykü Tekten

When my poetry first ventured outside — both literally and metaphorically — it found its way to you, a translator, and knocked upon the door of your language. Poetry is our master. From the beginning, our shared creed, our common compass, has always been poetry itself.

As you know, I am notoriously late — not only in life, but in poetry as well. I did not begin writing until my late twenties, perhaps even my early thirties. That is, by any measure, quite late.

Even as a reader, my connection to poetry arrived slowly. In Turkey, nearly every teenager plunges into poetry, both as reader and as writer. I failed rather definitively at both. My own reading life was unremarkable. I knew Nazım Hikmet, of course — some of his popular lines had lodged in my memory. Ahmet Arif, like Nazım, was beloved and familiar. And I had heard of Pablo Neruda. These well-known poets brushed against me in passing, but I never read any of them — Nazım included — with a steady, deliberate attention, nor in a complete way.

And yet, one day, poetry itself knocked at my door with a faith like no other and drew me back to earth — from that world of words and longing and defiance, that realm born of openness and clarity. Perhaps it would be truer to say: poetry blessed me.

In the Beginning

In the beginning, I sat down to look at the sky

The leaves were falling and the day was humid

Someone came and took away the words in my mind

Someone came and built a fire out of hay

Darkness is the quality of the night —I became

worthy of darkness

I drew a face onto the day with the chains of reality made out of light

the cloud was astonished

I reached out for the morning with the solitude’s pomegranate in the garden

I perspired once again and the horizon expanded

Each direction I looked deepened

The meaning marched into my eyes.

I settled inside the lines by reading again and again

My mind was familiar with the sounds of leaves, the candid

body of letters

All of a sudden, I looked for peace. There was a plethora of meaning

I denied the falling of snow, the waves of the sea,

the proliferation of life

They took me away from my own words, the tension of the bow,

the intense solitude of the sycamore, and my thirst

the moment when i reached the water.

I was poisoned by the reason.

Translated by Öykü Tekten

I have no poems committed to memory — not my own, nor those of the poets I most admire. I have always resisted memorization. For me, when a poem or a song is fixed in memory, it loses something of its mystery, that shimmer which should never be fully revealed. I want to preserve poetry in its essence, with its hidden depths and unreachable beauty.

On my desk rest the collected works of İlhan Berk, Turgut Uyar, Edip Cansever, Cemal Süreyya, and Ehmed Huseynî. From the earliest days of my poetic journey, these voices have accompanied me, and I believe they have guided me.

Even in prison, I found my way to Ted Hughes, Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, and E. E. Cummings. And beyond them, countless poets writing in Turkish and Kurdish cast their light into the darkness of confinement and offered me their hand.

I should also name Rênas Jiyan, who carried a vast breath into Kurdish poetry; the luminous Arjen Ari; and Kawa Nemir, who pairs his work as a translator with poetry of remarkable precision.

Now that I am free, I have both the joy and the privilege of discovering the books of a new generation of poets — and of coming to know them, one by one.

TMR: You write in both Kurdish and Turkish — two languages that differ profoundly. How does this duality shape you and your poetry? Should we think of it as the voice of one poet, or as two distinct selves? I ask as someone who also lives through more than one language, knowing how each can reshape the voice, the imagination, even the very ground of the self.

ÇOMAK: Kurdish and Turkish are very different languages, both in structure and origin. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly how this difference shapes my poetry. Yet I can say with certainty that I live in a space where their interplay is overwhelmingly positive — where the two languages nourish one another, offer greater flexibility of expression, sometimes weave together in fluid syntax, and yet insist on remaining distinct poetic realms.

Bond

There is an agony in my voice that women know

I am angry. My throat is parched.

I am carving myself out to fit into the day

This is my job! This is life! And I come down to the

the street with a freezing darkness

The needles knit my paleness, the shadow goes

towards the sea

The tuning of the night rust silently

A jaded pulse everywhere

And yet I have my bond with life.

Thunder in the sky, the leave changes colors

The chirps gather on the curtain of a hushed dawn

My face twitches with the depiction of astonishment

There is something on the wall, hard and unfit

for the desert

Maybe there is rain that doesn’t blend with water nearby

maybe on the rocks

The stone I turn to over and over again

suffocates me with its heavy consciousness, my arms are exhausted

My sentence expands with the uncertainty of the mist

And yet I have a strong bond with life

so strong!

Translated by Öykü Tekten

In a demanding art like poetry, this duality enriches imagery and associations, giving me a stronger footing in the act of invention. Turkish, as a cultivated and widely taught language, carries with it a certain swagger — or even a roughness, a privilege that shapes its presence in me. Kurdish, by contrast, persists defiantly, despite decades of denial and enforced forgetting. As a member of the Indo-European family, Kurdish possesses a complex structure that folds over the past to protect memory and identity — a fragile, emotional, unprocessed language that refuses compromise. It rehearses the future, cherishes childhood with certainty, and presumes a self that is inherently generous and communal.

In this multilingual context, it is possible, to some degree, to speak of two poets, two poetries. Yet within the world that language creates, the boundary between them cannot be fully defined. Almost everything that nourishes my poetry comes from my childhood. The world into which I was born through Kurdish is embedded in the foundations of both my Kurdish and Turkish poetry. It would not be wrong to say that the Turkish ‘me’ borrows from the Kurdish ‘me.’ This act of borrowing is not only tolerated — it is welcomed. The identities shaped by Kurdish and Turkish, and the voices they produce, do not stand in opposition.

I come from a Kurdish and Alevi world, shaped by its cultural codes. I never received formal education in Kurdish, due to state policies of discrimination and erasure. I began writing in Turkish, but even then, much of what emerged reflected the world I knew through Kurdish. Both languages have always been present in my writing, and I believe this has added depth and resonance to my poetry.

Once I attained a certain sensibility in Turkish, I carried that awareness — the value poetry instilled in me — into my Kurdish writing. In that sense, the world I inhabited through Kurdish nourished my Turkish poetry. Over time, recalling its debt to Kurdish, Turkish poetry refined what it had borrowed and returned it, I hope, in a richer form. No debt should remain one-sided. But if there is a debt to speak of, it is fair to say that Turkish still owes something to Kurdish.

TMR: I know, as one of your translators, your poems have been translated into English — could you tell us about translations into other languages?

ÇOMAK: Beyond English, my poems have found their way into German, French, Italian, Norwegian, Greek, Welsh, Hindi, Russian. In short, as far as I know, they have been translated into more than fifteen languages, each carrying its own echo of the originals.

TMR: Writing poetry in prison — and sharing it with readers — how was such a thing possible under the weight of so many restrictions and prohibitions?

ÇOMAK: Being a poet in prison — finding a way for the poems I wrote to reach the world, to break through gates and walls — required a level of difficulty I can hardly measure, and a stubborn perseverance in equal measure.

From the beginning, I had to confront the reality that my energy could not be devoted solely to the act of writing. The challenge was never merely to write good poems, or to recite them from a deeper, more refined place. Prison’s constrictive structure — the narrowness of its space, the slow, grinding passage of time — demanded that I draw upon a persistent and tireless love for poetry. I worked with discipline, devoting every day to poetry, to creating the possibility of illuminating the dark world around me with a single new line.

Yet creation alone was not enough. Getting my poems out, multiplying them, and sending them beyond the prison walls was another struggle entirely. Every word I wrote was under the surveillance and control of the administration. After weeks of delay, it could reach the outside only by letter. And always, there was the psychological strain: at any moment, a sudden raid could confiscate everything I had written. For years, I didn’t even have a desk of my own. Everything, in every way, seemed stacked against poetry.

Intellectual sustenance was another challenge. Reading is essential for a prisoner-poet, yet I was rarely able to access the books I needed. Requests were often denied, and I was allowed only seven books from outside every two months — like depriving a plant of sunlight and water. Perhaps the heaviest weight, however, was the impossibility of knowing how my poetry resonated in the outside world. There was no one beside me to read critically, to assess, to engage fully. That distance made the act of creation all the more difficult.

I must also correct a common misconception: that poetry merely requires free time, that it arises in moments of leisure. In prison, time itself is controlled, dominated by the system, and this is utterly antagonistic to poetry. Writing poetry in such conditions means stealing time from authority, carving space from hierarchy. It is one of the greatest challenges of the creative process. Time and space, in collaboration with the administration, become instruments of depletion, stealing from the human spirit, stealing from beauty. From the outset, I had to resist all of this, holding my ground with unwavering belief and passion for life and poetry.

Of course, my poems could not have reached readers through my efforts alone. This was a collective labor. For many years, my sister Suna acted as my contact on the outside; more recently, İpek, who became my legal guardian, took on this role in Turkey and abroad. My editors, though they had no direct access to me, worked with care and dedication. Poets, publishers, and human rights organizations — especially PEN — also played a crucial role in bringing my poetry beyond prison, allowing it to resonate across the world. I must always acknowledge the vital part played by all these individuals and institutions.

TMR: You spent thirty years, three months, and eight days in prison. I am deeply curious — what did it feel like on the day you were finally released?

ÇOMAK: The day I was released, I was shaken by a kind of anxious joy. I was anxious because — just as I hadn’t been released on August 21 — I feared I might once again be kept incarcerated on some arbitrary grounds. I couldn’t surrender myself to the freshness and lightness that the reality of being free might bring. So, I waited for the moment of decision with cautious hope, but a hope that left no room for despair.

When I finally heard, though late, that I would indeed be released, there was at first a wave of intoxicated emotion in me — an urge to cry out, a shout I barely restrained, and tears I held back with difficulty. I almost burst into tears. Truly, I almost did.

That state lasted only for a moment. Then, I withdrew once more into my own voice — the voice that had carried me through all these years, growing ever stronger — and into the space of selfhood shaped by those feelings and thoughts. I suppose that’s what we call being realistic, or mature. Because the decision could still be reversed at any moment. My release could still be prevented.

I had to wait until evening. And so, I waited.

When I returned to the ward after receiving word from my lawyer — that the prison administration had given a positive opinion regarding my release, but that the final decision would rest with the enforcement court — I saw that my friends were waiting, full of curiosity, eager to hear what I had learned. When I said, “I’m going to be released,” the cheers, the whistles, and the tears that rose up from the ward echoed off the walls, announcing to me, over and over, that freedom had become a very real possibility.

You would have thought the horses galloping through my blood had leapt into the eyes and veins of all 31 of my cellmates.

Later that evening, at 8:30 p.m., I was released — carrying with me not only my own feelings but also the sorrow of the friends I was leaving behind. I was physically tired, but the silent strength of freedom cutting through the darkness gave me resilience. It wasn’t until the soldiers put me in a van and dropped me outside the prison walls — into the night, into the unknown — that I finally began to believe I was free.

At first, I was somewhat numb. Maybe I couldn’t quite believe it yet. Maybe I was still emotionally distant because my feelings hadn’t caught up with the reality. I was a little removed from myself. But the moment I embraced my loved ones — when I held them tight in my arms — that was the moment I believed. I believed in my freedom, in myself, and in them. It was a dark day, and the night became our light.

TMR: During our first phone call, you were walking down İstiklal Street. There was a joy and wonder in your voice, like that of a child seeing snow for the first time, or catching sight of the sea. I’d like to return to that moment and, from there, move a little into your life before prison. Can we begin with Bingöl, and then talk about your student years?

ÇOMAK: Since gaining my freedom, almost every day feels like stepping from one world into another entirely.

Of course, I have not forgotten the past — life from thirty years ago. Yet one truth is undeniable: I have entered a new life, a new time. People have changed. Places have changed. Relationships have changed. Nothing remains untouched.

I have no fixed standard of comparison, no reference point for this transformation. It feels truer to say I have entered a brand-new world — one I must learn, memorize, and absorb from scratch.

Loved ones await whose graves I have not yet visited. Cousins I remembered as children now greet me with their own children — children the same age they were when I last saw them. All my nieces and nephews were born while I was imprisoned. My grandmothers passed away. Homes I once knew with closed eyes now require guidance to find.

Again and again, I say: everything has changed. And yet one thing remains unaltered — the sparkle in the eyes of those I love. Their embrace carries the same tenderness, longing, and unconditional acceptance as ever. This umbrella of love has been essential, allowing me to navigate this vast, altered world without stumbling. I am profoundly grateful for it — truly, what a blessing.

Bingöl, the city in which I was born, remains a country I have yet to visit. It is more accurate to call it a hidden world, one that gave me a sense of being. I have spoken so often of Bingöl — of the relentless love I feel for it, of the foundation it laid in me, of my childhood, my student years, my early youth, which inevitably shaped my poetry — that I fear speaking more might wear it thin, dulling its memory. Yet childhood never truly leaves us.

I will say this: the foundation for being a good child, a good person, a good poet, was laid in the Bingöl of my youth. The values instilled there have carried me to this day — and made this conversation possible.

Yes, we first spoke while I was walking down İstiklal Street. That freshness, that childlike wonder you heard in my voice, is still alive, dear Öykü. My hunger for life is passionate, for this world is new to me, brimming with things yet to unfold, things I am yet to grow into. Beauty overwhelms me.

Sometimes I watch the people and objects around me — the waves of the sea, the hum of the crowd, the blare of horns, the fierce insistence of seagulls, the gentle brush of cats against my legs, the vast ferries, and freighters. And suddenly, I rise — rising like a bird, detached from myself, joining this beautiful, unfamiliar world, anchoring my existence within it.

In that moment, I am overcome, as if hearing a deeply stirring folk song.

It is something like poetry, you see.

TMR: As our conversation draws to a close, it is clear that poetry, memory, and resilience are inseparable in your life. From the hidden worlds of childhood to the constricted spaces of imprisonment, and finally into the expanse of freedom, your voice has remained unwavering, luminous, and profoundly human. Your words carry me through time and space, illuminating the weight and wonder of what it means to be both witness and participant in (your) life’s transformations. I am grateful for your honesty, for the way you allow us to feel the unfolding of a world reborn through your eyes. The tenderness you describe, the childlike wonder, the grounding power of love — these are not only the scaffolding of your poetry, they are also the threads that bind all who read it to your experience. Thank you for sharing this journey, for letting us glimpse the depths of memory and the heights of discovery, for reminding us that poetry is a vessel that carries the human spirit, even across the longest winters.

ÇOMAK: Thank you — for listening, for holding space, and for letting poetry speak between us.

This interview has been edited for length. Translated from Turkish by Sevda Akyüz.

* PEN International’s campaign for imprisoned writers runs from November 15 to Dec 10, 2025.