Ahmed Farouk

Twenty years ago, I would have never come up with the idea to translate a text by Walter Benjamin, for I would have doubted my ability to reproduce the intensity of his language in Arabic. At the time, I had already read, in German, both Benjamin’s famous essay, “The Artwork in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility,” and his study of Goethe’s Elective Affinities in German. However, no direct Arabic translations of Walter Benjamin had yet been published. The Egyptian translator Ahmed Hassan had undertaken this difficult task and translated the main essays of Benjamin in two volumes (2004/2007) — not from German, however, but from English and French. Eventually, he approached me for a collaborative translation of Einbahnstraße (One Way Street, 1928) and Berliner Kindheit um 1900 (Berlin Childhood Around 1900, published posthumously in 1950). These two volumes are considered to be Benjamin’s main prose works. Both are fragmentary in nature. They contain quite different reflections about Berlin and modern life.

I admit that at first, it was hard to figure out what Benjamin was up to with Berlin Childhood Around 1900*. When Hassan was still in the process of translating One Way Street, I was tempted to translate small fragments of Berlin Childhood, but I remained undecided. Hassan‘s translation finally appeared in 2008 in Amman. I meanwhile worked on the Berlin Childhood chapter “The Socks” as a sample. It was not the most beautiful text in the book, but I was delighted with the lesson it gave me in form and content. Then, in 2010, I received an offer to publish the translation of the book as part of the “Kalima” translation project in Abu Dhabi.

In terms of size, Berlin Childhood was the shortest book I had ever translated. But the process took over a year. After the first six months, there was a draft translation with which I was not satisfied, a skeleton, without flesh and soul. Additionally, I was not sure that I had understood certain parts correctly. Then a long process of reshaping began, which took another six months.

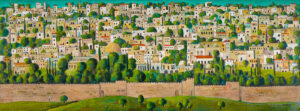

It was clear to me that Berlin Childhood was neither an autobiography nor a turn-of-the-century Berlin book, but rather a kind of documentation of a childhood in a city abandoned once and for all by the writer. It took the form of stand-alone essays born of different stages of Benjamin’s flight from Nazi Germany, when he first went to Paris in 1933 and later attempted an escape over the Pyrenees into Spain in 1940, the failure of which caused him to commit suicide.

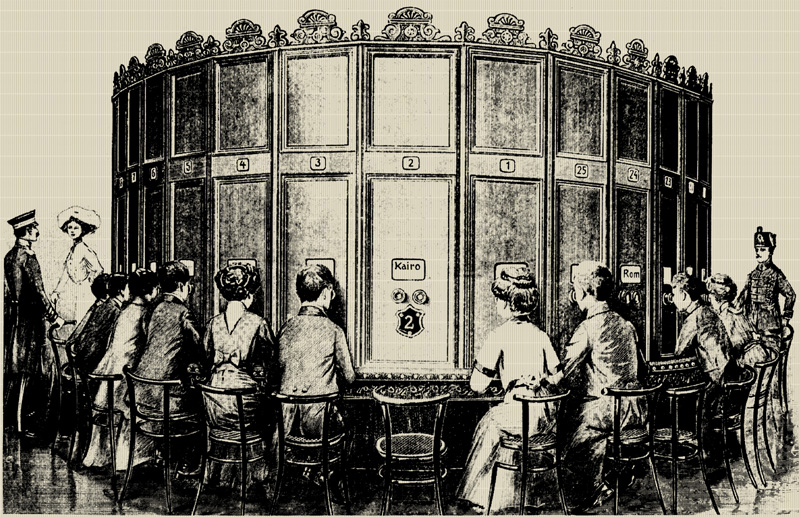

At first, I tried to breathe the air of the original text, which is composed of thirty short chapters totally independent of any timeline, each focusing on one or two items or events from the author’s childhood in the city. Some chapters clearly reflect the spirit of the time, such as “Kaiserpanorama,” “The Telephone,” “Pfaueninsel” and “Glienicke.” In this last one, you can see how sport became important to the Berlin bourgeoisie at the turn of the century and how people tended to make a spectacle with their sport uniforms. Another glimpse of a particular time and place comes through in “The Telephone,” which shows how the introduction of the device to private homes changed the life rhythm of the people in Berlin, and how unfamiliar its ringing sounded. In the beginning, it was left totally neglected in the corridor, but then it took its royal place in the center of the living room and became an essential object in life.

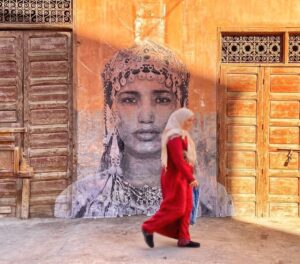

As it happens, the Kaiserpanorama can now be seen in the Humboldt Forum, a huge round construction that included seats and a mechanically operated camera-obscura slide show. It was popular at the turn of the century, before the advent of cinema, as it allowed you to look through two lenses and watch a variety of spectacular, exotic or touristic images from faraway countries.

Most of the chapters are emblematic in nature; even though they do not deal with people, but rather with objects, they create a sort of memory room, such as “Being Too Late,” “Lads’ Books,” “Two Riddle Images” and so on. The ensuing fragmentary character is even more reinforced by the associative and essayistic character of the prose itself. Some chapters reflect peculiar fantasies, like “Crooked Street” or “Company and Cupboards.” In fact, the images of a happy middle-class childhood, which Benjamin missed in his adult life, a time when he was actually unable to fulfill his basic economic needs, shine through in “The Fever,” “Butterfly Hunt” and “Christmas Angels.” All in all, we have a diverse range of memories exploring the city, where the child encounters poverty, sex and secrets the city keeps from him, among other things.

Translation Issues

Certainly, the text, through the intensity of its language and its high ability to represent memories that mix reality, dream, and children’s fantasy, is very well suited for “survival” (Überleben) in a translation. But because of the peculiarity of Benjamin’s sentence structures, which often demand to be reread, their reproduction in Arabic needed a long process of refinement. It was interesting, though, that paraphrasing or providing additional explanations in the translation was not necessary. Nevertheless, I had to use footnotes to explain names and historical backgrounds and so on. Footnotes also helped me to elucidate names of specific locations associated with allusions, such as the Markthalle (lit. market hall), or Hallesches Tor, which I had to translate literally.

Eventually, I found a key to incorporating the original offered to me by Benjamin himself, in a small text “Digging and Remembering” (Ausgraben und Erinnern) from the “Walter Benjamin Archive. Bilder, Texte (2006)”:

Anyone who seeks to approach his own spilled past must behave like a man digging. Above all, he must not be afraid to come back to the one and the same thing over and over again — to scatter him as one scatters earth, to reroute it, how to rake soil … and certainly it is useful to proceed according to plans when digging. But just as indispensable is the cautious, tentative ground-breaking in the dark soil. And he deceives himself for the best, who only makes inventory of the finds and cannot designate the place where he keeps the old in today’s soil.

It seemed to me that this was the deliberate technique that Benjamin used in compiling the book when he had already turned his back on his hometown. And so I realized why the book begins with the uninhabitable “loggias” and ends with the “Little Hunchback.” The tension between remembering and forgetting lends the work its poetic quality.

And so I must confess that in translating I had the increasing feeling that I was closest to Paul de Man’s term, “the intangible rest.” Although I believe that my translation of some pieces, such as “The Telephone,” “Winter Mornings,” “Two Enigmas,” “Misfortunes and Crimes” at least “do not hide the light from the original“ (dem Original nicht im Licht steht), there are passages that contain an undiminishable ambiguity, as in “Butterfly Hunt”:

“It (The Word) has preserved the unfathomable, with which the names of childhood face the adult.”

Es (Das Wort) hat das unergründliche bewahrt, womit die Namen der Kindheit dem Erwachsenen entgegentreten

“لقد حفظت هذه الكلمة ما لا يمكن سبر غوره، وما تواجه به أسماء الطفولة الشخص البالغ.”

Or with a poetic note in departure and return:

Mancher Blick hat sie vielleicht gestreift, wie in den Höfen. Fenster, die in schadhaften Mauern stecken und hinter denen eine Lampe brennt.

“Many a gaze perhaps touched on them, as if those windows which look out of dilapidated walls in courtyards and in which a lamp is burning.”

“رب نظرة قد تجوب هذه الجدران مثلما تجوب الأفنية. نوافذ محشورة في جدران مهدمة يشتعل مصباح خلفها.”

Even in “Beggars and Whores” I am fascinated by the final sentence:

Wenn ich dann manchesmal schon gegen Morgen in einer Torfahrt inne hielt, hatte ich mich in die asphaltenen Bänder der Straße hoffnungslos verstrickt, und die saubersten Hände waren es nicht, die mich freimachten.

“When I finally came to a halt beneath an entrance way, sometimes practically at, I was hopelessly snared in the asphalt meshes of the street, and it was not the cleanest hands that disentangled me.”

“وعندما كنت أحيانا أتوقف قرب الصبح عند مدخل أحد البيوت، أكون قد وقعت بلا أمل في حبائل أربطة الشارع الإسفلتية، ولم تكن أنظف الأيادي هي التي حررتني منها.”

The idea of asphalt meshes seemed vague but beautiful to me. This ambiguity also has another form, and this fantasy, which brings details and objects to life as in society:

“In Wahrheit hatte sie (die Gesellschaft) sich nur in die entfernten Räume zurückgezogen, um dort im Brodeln und Bodensatz der vielen Schritte und Gespräche zu verschwinden, wie ein Ungeheuer, das, kaum hat es die Brandung angespült, im feuchten Schlamm der Küste Zuflucht sucht.

“In reality, it (the society) had merely withdrawn into the distant rooms, in order there, in the bubbling and sedimentation of many footsteps and conversation, like a monster which has just washed up on the tide and seeking refuge in the damp mud of the shore.”

“وفي الحقيقة فإنهم قد انسحبوا للغرف البعيدة لكي يختفوا هناك وسط الغطغطة ورواسب الخطى الكثيرة والأحاديث، مثل وحش لم تكد الأمواج تقذفه إلى الشاطئ حتى هرع ليجد ملجئا في طينه الرطب.”

When I finally finished the translation, I hoped that it came close to Benjamin’s own ideas, as he considered that translation “touches the original lightly and only at the infinitely small point of the sense, thereupon pursuing its own course according to the laws of fidelity in the freedom of linguistic flux” (Walter Benjamin, from “Task of the Translator,” translated by Harry Zohn). However, today, when I reread the original text, I can’t help but wonder how I managed to translate Walter Benjamin at all, and if there has not remained a hint of the untranslatable.

*The English quotations of Berlin Childhood around 1900 are translated by Howard Eiland.