On Sunday, Oct. 29 at 1pm Eastern/19:00 CET, The Markaz Book Group will be discussing the late Khaled Khalifa’s novel No One Prayed Over Their Graves, a sweeping tale of Aleppine society at the turn of the twentieth century from provincial villages to the burgeoning modernity of the city, where Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived and worked together.

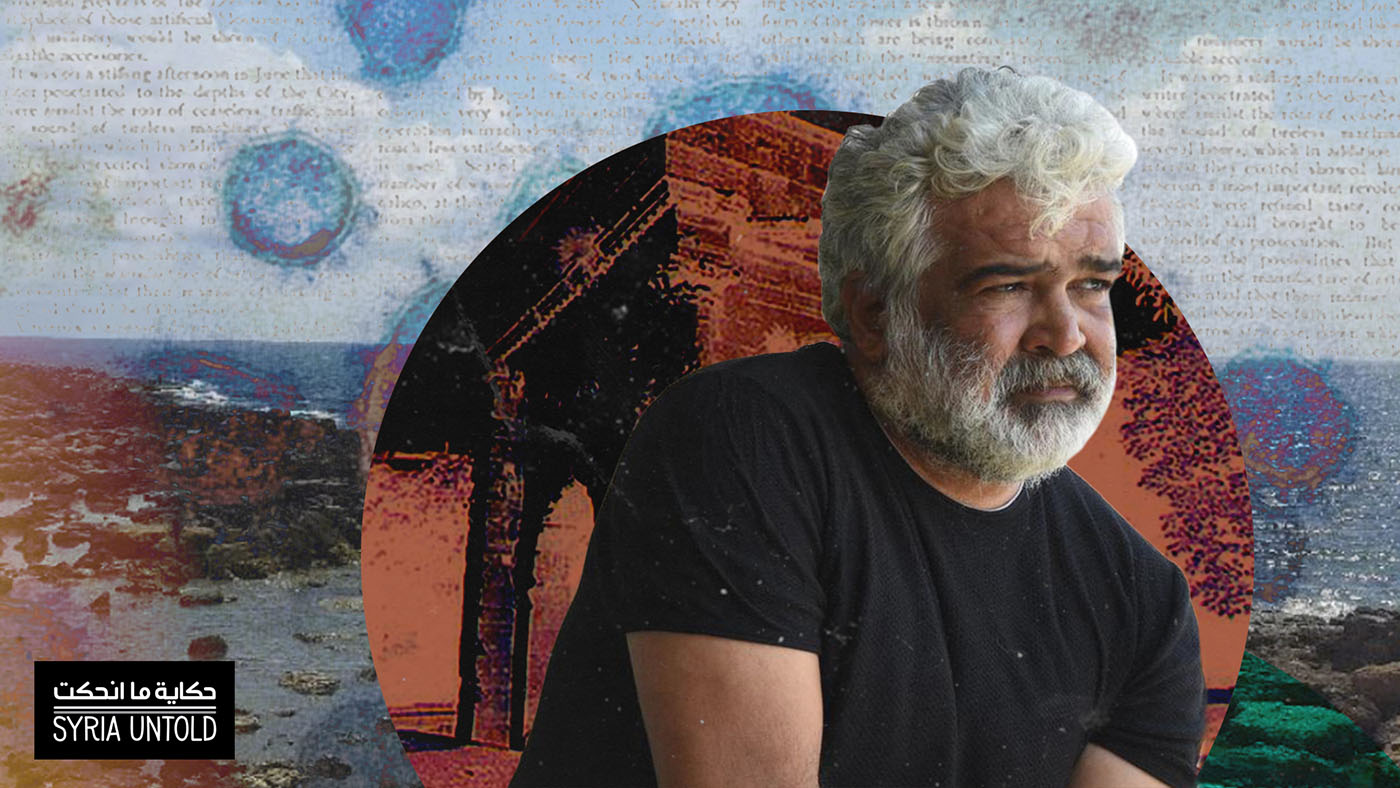

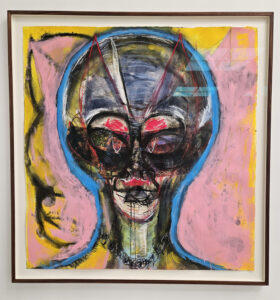

I remember Khaled in a beer garden in Bristol. He was sitting at a table performing the English language: “So so so,” he sang. “And and and, but and but! and so… but! so… but!” Khaled inhabiting his stocky body, his warm, brimming smile, his big head of fluffy white hair.

Of course he knew far more words than those. He somehow managed to communicate very well in English without speaking it very fluently. In Arabic he talked and talked, like the tide. Sometimes he broke into song. His writing was brilliant, the kind that will last for many generations. A poet, screenwriter, novelist — he was endlessly playful with words. And he was gentle with life, and with people. He took them very seriously.

I was with him at the BBC one evening in June 2013. ISIS had captured Mosul, and using the money looted from the city’s banks, and the American weapons captured from the fleeing Iraqi army, the organization had rapidly seized vast swathes of eastern Syria — areas which had been previously liberated from the Assad regime. The radio presenter asked Khaled what he thought of it all. His answer — “It’s important to pay attention to the role of Iran” — may have confused non-experts at the time, but was absolutely apt.

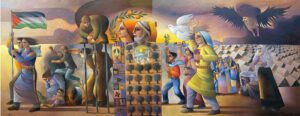

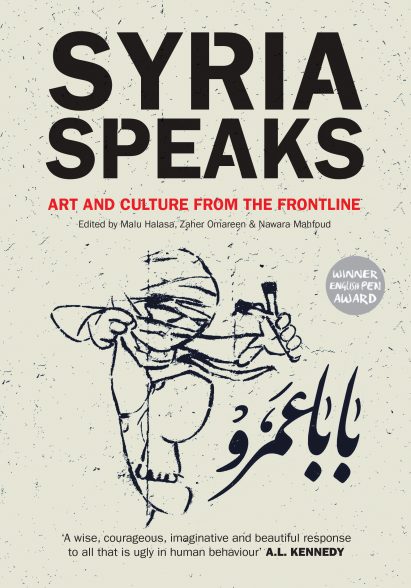

He was politically acute, although he wasn’t primarily a political person. He was a humanist, an artist, and a Syrian who cared deeply about Syrians. Once, as we toured England to introduce the Syria Speaks anthology, Khaled met refugees from villages near his own in the Aleppo countryside. “They asked me about the olive trees and the seasons,” he grinned afterwards. “I love these people.”

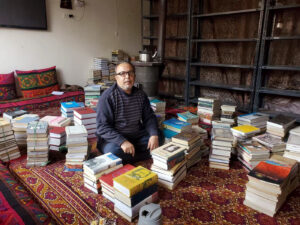

To read is to defy the Syrian regime — Khaled Khalifa

He liked the concrete, material detail of life, and was aware of the dense social webs connecting people. This comes through in his writing, in its sensuousness and physicality as well as in its careful intricacies of plot and character. His novels are beautiful and rewarding, but not necessarily easy reading. The stories proceed in narrative swirls and mosaics rather than in linear fashion. This form manifests a kind of realism, because in real human life everywhere, not only in Syria, characters are woven from stories, and stories link to further stories …

Khaled loved the endless diversity of humanity in general and of Syrian society in particular. He saw Syria as heir to many civilizations, and rejected as absurd the notion that it might fit into a single rubber-stamped identity. He opposed all forms of authoritarianism. He grieved that the world’s powers had opposed the Syrian revolution, and was angered that international extremists had been allowed to travel so easily to Syria. He rejected the imposed binary of religious tyranny or secular dictatorship, and hoped instead for democracy, which he called “the future.”

He saw Syrians as plural, and understood their diversity as a strength. But he lived under a regime which considered diversity a weakness to be exploited, or a weapon to wield.

His books were banned in his own country, but still they were widely read there. He used to tell the following story: He was returning to Syria from Lebanon, and at the border post a guard squinted at him through the car window. “Are you Khaled Khalifa?” he asked. “Wait there.” So Khaled waited, wondering what was coming next. A few minutes later the guard returned with a copy of one of the novels. “Please sign it,” he said. “It’s for my wife.”

Khaled called the novel “the most effective art form for dismantling the narrative of tyranny and oppression.” His life was lived on this frontline. When I first met him, in 2012 in Beirut, his arm was still in a sling after being broken by regime goons during the funeral of murdered musician Rabee Ghazzy.

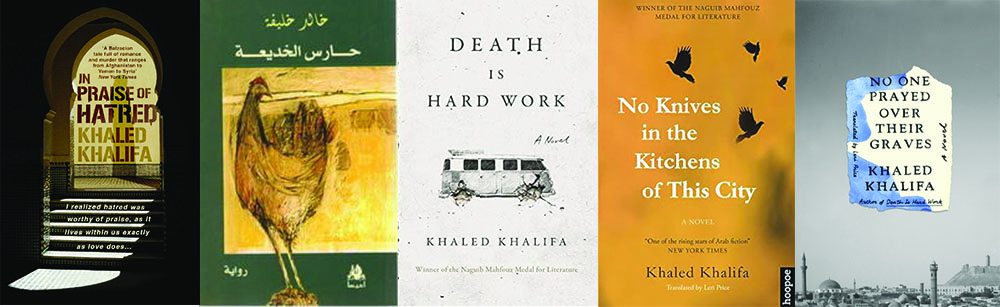

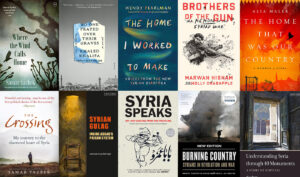

That was shortly before his third novel, In Praise of Hatred — winner of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction — was translated into English by Leri Price, bringing him international as well as regional fame. (I was honored to write the introduction to the English version.)

The book prefigures the current social breakdown by returning to Aleppo in the 1980s, when the violence of the Baathist regime clashed with the intolerance of the Muslim Brotherhood. It takes on sectarianism and misogyny, and recommends tolerance. The novel after that, No Knives in the Kitchens of this City — winner of the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature — ranges over three generations from World War I to the invasion of Iraq. It paints a picture of multicultural Aleppo and its open possibilities, on the one hand, and the dictatorship, and shame, and the rage to conform, closing them down, on the other. “It is the duty of writing,” said Khaled, “to help break down taboos and clash with fixed and backward concepts.” And in No Knives he created a gay character (the narrator’s Uncle Nizar) which he treated with sympathetic sensitivity.

An open-hearted tolerance may have been Khaled’s defining characteristic as a man as much as a writer. He was a remarkably social man, very highly valued by his friends. I didn’t spend much time with him, but I certainly felt he was my friend. I suspect countless other people felt the same. He was entirely without conceit or pretense. Even after his fame, he preserved his absolute humility.

His fiction was always set in Aleppo, the city and its countryside, and that was where he was rooted. But he moved to Damascus, and all through the war he remained in his flat in the suburb of Barzeh, on the mountainside, with a view of the active destruction. He endured years of bombing. Sometimes planes hovered above his building to fire missiles south into the Qaboon neighborhood. At first, he stayed because he thrived in the social context of the capital, but that faded as people left and the streets became clogged with checkpoints. “Cities die just like people,” he wrote in No Knives.

In Beirut in 2012 he’d told me that he found it easier psychologically to be in Syria than outside, despite the violence and repression, that he worried more for his friends inside Syria when he wasn’t with them. But by the following year, he’d changed his reasoning. “Every time I leave the house I look at my things for the last time,” he said. “But what can I do? It’s my country, my revolution. My situation is no different to any other Syrian’s. As a writer, it’s important to stay and to reflect the reality of what is happening.”

In Lina Sinjab’s short film Exiled at Home (2019) he talks of his solitude. By then, most of his friends had left. He too sometimes left for a few months at a time, to do residences abroad, but he always chose to return to Syria.

In the end, though, war is war, and it wouldn’t be over easily or quickly. It carried its stench with it wherever it reached, wafting over everyone, leaving nothing as it had been. It altered souls, thoughts, dreams; it tested everyone’s capacity for endurance. —from Death is Hard Work

“This is my country,” he says in the film. “My home is here, my family’s here, my mother is buried here. So it’s my country. I don’t have anywhere else.”

And nowhere else had Khaled. Syria and Syrians are immensely proud of him. It was important to Syrians that in this time of infamy they could boast such a consistent producer of world-class culture as Khaled, such a crafter of jeweled beauty, word to word, sentence to sentence.

And it is important that Khaled chronicled the current collapse, for our present and future consideration.

His novel No One Prayed Over Their Graves, which was published in Arabic in 2019, opens with two friends returning home after a night of drinking to find that their whole village, their families and friends, have been wiped away by a flood. As a metaphor, it works very well for the last Syrian decade.

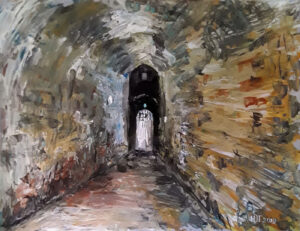

Death Is Hard Work, in English also from 2019, addresses the war directly. This novel recounts the journey of two brothers and a sister bearing their father’s corpse from southern to northern Syria for burial. The journey by road should take a few hours. It lasts three days through endless checkpoints. The corpse degenerates as does the relationship between the siblings. In many of his novels, Khaled was a keen observer of the Arab family fracturing under the stresses of war, politics or social mores.

The idea for the Death Is Hard Work was sparked in 2013, when Khaled was lying in hospital after an earlier heart attack. He lay there and wondered, if he died, how his family would be able to take his body home in these war conditions.

He was buried in Damascus. He wasn’t taken home.