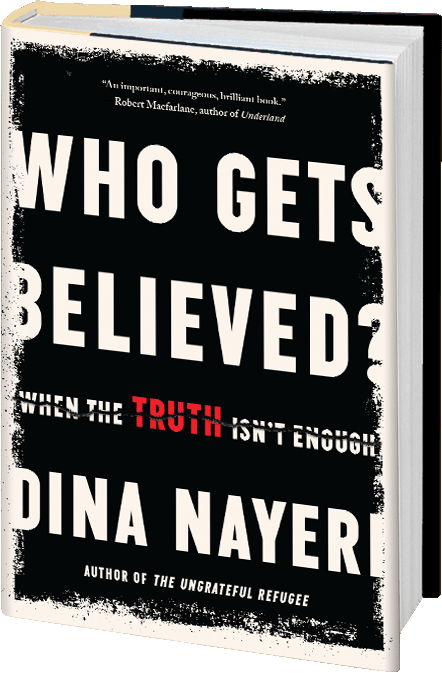

Mischa Geracoulis reviews the new book from Dina Nayeri on refugees and asylum seekers who must be believed to get through the system.

Who Gets Believed? When the Truth Isn’t Enough by Dina Nayeri

Catapult Books 2023

ISBN 9781646220724

Mischa Geracoulis

In this 21st century cancel culture rife with fake news, revisionist histories, competing agendas, and heightened polarization, truth and facts are on shifting ground. As of January 2023 in the United States, for instance, there were 227 bills in 40 state legislatures designed to limit or ban honest discussions about race and the country’s history of racism. Limiting academics’ freedom to tell the truth about race is not new, but the ramifications for American education are chilling.

Once upon a time, what was true was the opposite of what was false. With facts established, truth was durable, solid, and tough enough to stand on its own. Now, though, facts are displaced not by substantiated new evidence, such as that provided by a scientific breakthrough or forensic investigation, but by anyone able to align a convincing narrative with a personal, political, or corporate preference. The sheer volume of propaganda, lies, conspiracy theories, and public fighting over known facts makes for an atmosphere teeming with mistrust, intolerance, and hostility.

In 2016, “post-truth” was Oxford Dictionaries’ word of the year, marking the advent of a phenomenon that accelerated from fringe to mainstream, whereby “objective facts are less influential.” Against this backdrop, Dina Nayeri, an author and professor of creative writing at the University of St. Andrews, has undertaken an ambitious exploration of truth.

Threaded throughout the book and across a spectrum of circumstances is the inborn human desire not just to be believed, but to be accepted and to belong.

Partly a recounting of interviews and reports, partly confessional, Who Gets Believed? When the Truth Isn’t Enough is an investigation into what constitutes “truth,” and by what means and by whom truth is determined. Presumably propelled by her own trajectory as an asylum seeker from Iran who became a naturalized United States citizen, Nayeri relays several stories by refugees and asylees who have pleaded their cases far from home, often to those with little or no understanding of their culture or language. Other “true” stories are told from the standpoint of legal, psychological, and medical authorities, and serve to expose the fact that truth is speculative.

Interspersed among these stories are excerpts from the author’s life, darting from past to present and back again, comparing and contrasting experiences of being subject to the scrutiny of others and oneself. On the latter point, some of Nayeri’s personal revelations are decidedly cringe-worthy and superfluously intimate. The intricacies of her post-partum, “most taxing bowel movement” are a case in point. Other over-shares are of the emotional processing variety — guilt, it may be inferred, for not believing that her partner’s brother suffered with mental illness, and for not partaking in her mother’s belief in an evangelical Jesus.

Other depictions in these pages give examples — both mundane and exceptional — of the ways and means by which truth receives its stamp of approval. Whether the truth quotient is ascertained by a family member, romantic partner, religious adherent, medical examiner, police officer, judge, or border control official, it distills down to the believability of the person under scrutiny. A Kenyan woman seeking asylum in the U.K. in order to escape female genital mutilation (FGM) gets denied because asylum officers — unfamiliar with women in such circumstances — see “reasonable doubt” in her story. “Who is to say what cuts on upper thighs mean? Those who’ve worked in Kenya [would] know that [this] woman…very likely got those cuts in an FGM struggle. Are we to punish her because she didn’t let them finish the job?” Truth, Nayeri shows us, is sketchy and almost always under suspicion.

Every culture, she writes, has its own measure for what “real truth” is. Usually displayed by acceptable words, sounds, and appearances, conveying truth, like the act of storytelling, is shaped by culture and society. And just as there are myriad ways in which human beings tell their stories, truth is revealed through any number of avenues. Iranians, she cites, need time to tell their truth, rarely answering a question with a clipped yes or no. The heart of a matter is gotten to in roundabout fashion, insinuating seemingly unimportant details into a narration, until eventually arriving at the point of fact, or at least a tolerable truth.

Turning to the work of Blaise Pascal, Nayeri quotes the philosopher’s instructions. “Kneel down, move your lips in prayer, and you will believe” encapsulates Nayeri’s conviction that religious truths are conferred through repetition of rituals. Or, as exemplified by the Fox News model, political campaigns, cult leaders, conspiracy theorists, and sales adverts repeat something often enough and loudly enough, and it becomes accepted as true. Repetitious pronouncements serve multiple ends, irrespective of truth.

For Harvard Business School (HBS) graduates, confidence equates to an achievement of airtight believability. Statements made with conviction — no matter the factual validity, historical evidence, scientific data, or basic reasoning — are the stuff of negotiation, capitalism, and politics. For all the to-do about leadership and changing the world, HBS essentially teaches believability. More specifically, students learn to present themselves in such a manner that others would want to believe them. HBS instills in their students a belief system; it cultivates credible voices, and teaches them to be self-assured in knowing that they’ve got something others want. Nayeri wonders what it might be like if a refugee or asylum seeker exuded that attitude: “I don’t need them (asylum granters); they need me!”

Refugees and asylum seekers, of course, rarely have the luxury of such training. Dr. Katy Robjant, Freedom from Torture’s director of national clinical services and Trauma Treatment International’s co-founder and advisor, explains to Nayeri the body’s fight-flight-freeze mechanisms, and how trauma is processed in the brain and body. The amygdala and hippocampus parts of the brain, for instance, each have significant roles in the ways that humans record action, emotion, sensory input, and other detail, but through different pathways and to different results. Consequently, says Robjant, if an asylum officer or judge comes to a verdict without any knowledge of how the brain processes contextual versus sensory information, an unfair decision to discredit an asylum seeker’s story may result. Moreover, according to Dr. Juliet Cohen at Freedom from Torture, the asylum interview experience can be traumatic in and of itself, especially because interviewers use questioning tactics meant to screen for inconsistencies and any sign of deceit.

Amygdala and hippocampus aside, logistical discrepancies in an asylum seeker’s story can be mistaken as lying gone awry. Nayeri gives the example of something as ostensibly straightforward as one’s birthdate. Due to differences between the Persian and Gregorian calendars, one might come up with more than one answer to the birthdate question. If the asylum seeker is “a functionally illiterate Iranian villager from another era, with undiagnosed autism, [or] a head full of superstition” who marks dates not by a calendar but by the heavens, then accurate dates are all the trickier to establish. Throw hired translators into the mix, and depending on the translator’s word choice, opinion — expert or novice — and personal biases, truth can be further waylaid.

Although the Refugee Convention has a fixed definition of “refugee,” national administrations do not always abide by it. Apparently, asylum officers have rejection quotas to meet, for which they are often rewarded. “Even a minor functionary,” as Nayeri puts it, has the power to dismiss an asylum seeker’s case by claiming to detect lies in the petitioner’s story.

The American Psychological Association asserts that lie detection is mere chance. Seconding that assertion is the former FBI agent whom Nayeri interviewed for the book. The agent comparably maintains that while there are the rare few agents who are adept at detecting lies, it’s mostly a game of chance. The accuracy rate even for interrogators trained in micro expressions is only 60%, despite, for example, the convincing popularity of the TV series Lie To Me (2009-2011), starring Tim Roth, whose lie detection skills never fall short. Dr. Paul Ekman, upon whose life work the TV show was loosely based, has argued that while deception detection skills can be learned, there really is no perfect lie detector.

Threaded throughout the book and across a spectrum of circumstances is the inborn human desire not just to be believed, but to be accepted and to belong. Sometimes believability follows Occam’s razor; more often, truth fails to walk a straight and narrow path. Who Gets Believed? is a testament to the power of words and their ability to decide the fate of a life, or many lives. For anyone who stands trial, has been falsely convicted, has gained or been denied asylum, the judge and/or jury are arbiters of destiny — at least on earthly planes of existence. Nayeri turns frequently to matters of faith and religion, particularly her own doubts, and summarizes wisdom borrowed from French Christian mystic Simone Weil (1909 – 1943). “False things give the impression of truth, and true things seem false,” maintained Weil, making the point that any affirmation of truth really does come down to who gets believed.