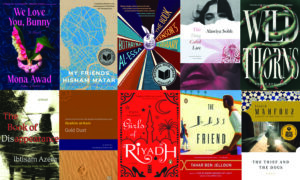

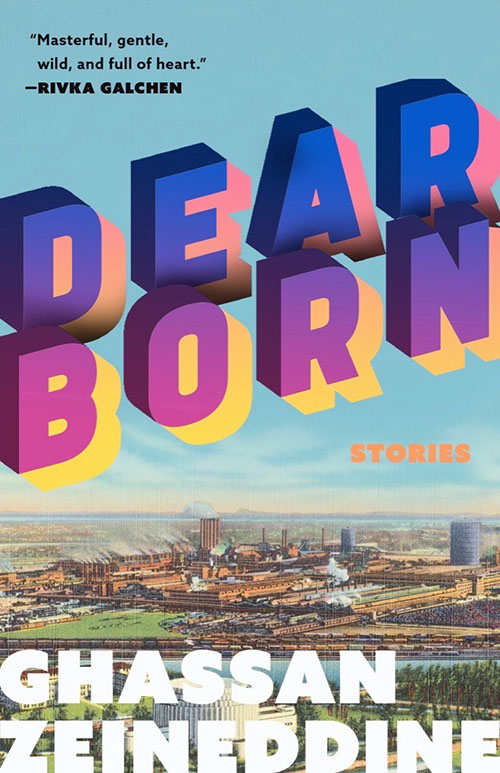

Dearborn, stories by Ghassan Zeineddine

Tin House 2023

ISBN 9781959030294

Youssef Rakha

I interrogated Ghassan Zeineddine’s Dearborn harshly before I embraced it. I had to. In these fictional accounts of Arab American experience, the characters’ identity can come across as almost generic: not just hookahs and hijabs, but war-torn homelands, oppressed women, closet queers, and far too many tribally minded exiles lurking in the background.

This is not something the ten short stories making up the book state so much as imply, but most first-generation immigrants here — and these are foundational figures even if they are not the protagonists — are religious, materialistic, and resistant to change. They live in perpetual tension with almost every aspect of their adopted society: law and order, personal rights, non-Muslim and secular traditions. They may have been forced out of their home countries — the reason most frequently given is the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982 — but, even when they can safely return to those countries, they seem desperate to stay and accumulate money while remaining clammed up in their small, blinkered community, living more conservatively than they would if they had never crossed the ocean in the first place.

The protagonists themselves are mostly second-generation, better adjusted to Western society and the contemporary world, but they are burdened enough by their parents’ legacies that the sense of insularity is pervasive.

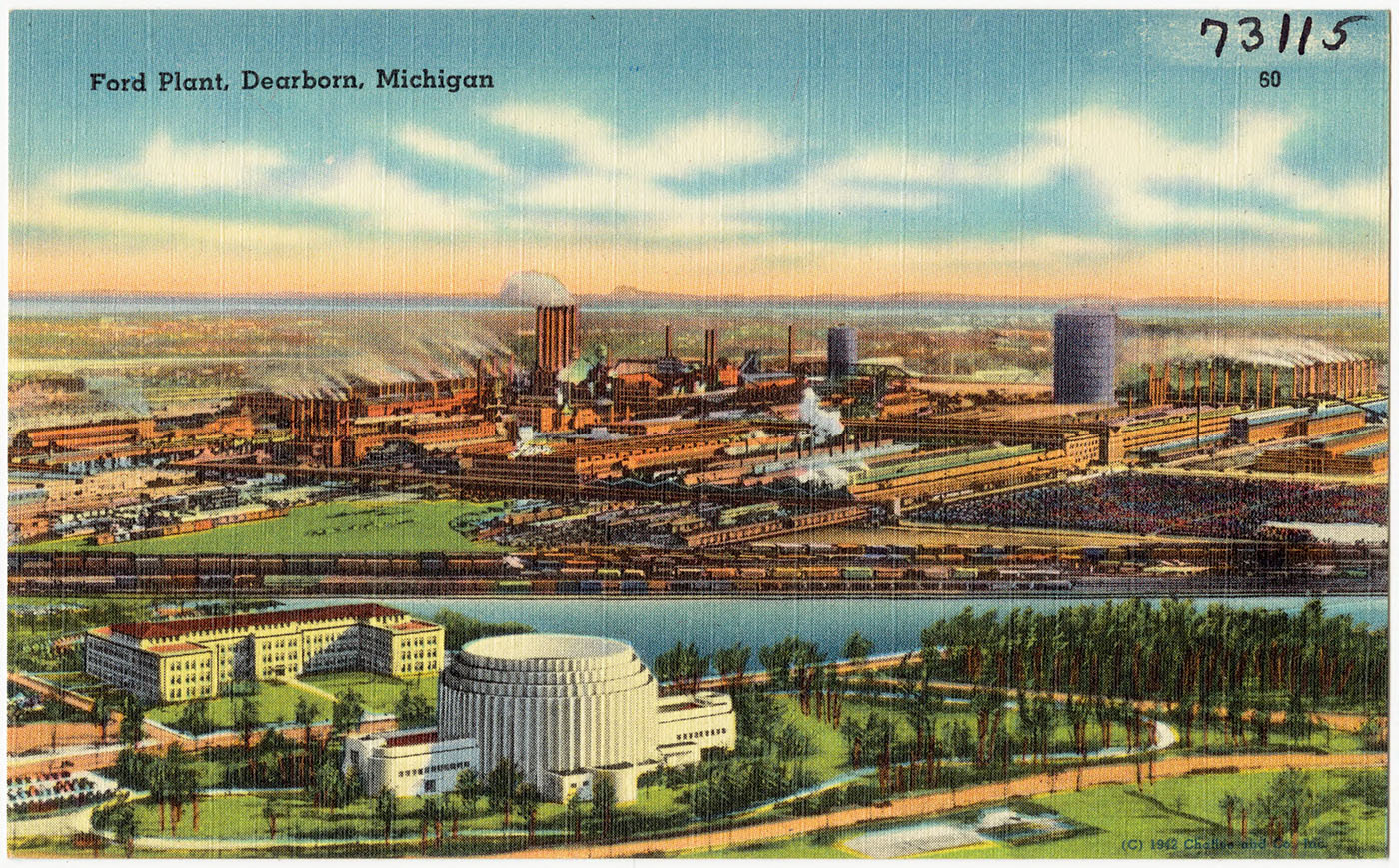

This is hardly Zeineddine’s problem, of course. Dearborn, Michigan — the collection’s setting and, emblematically, its theme — has the US’s largest per capita Muslim population, and it’s probably even more claustrophobic in real life. My concern is that the worldview which informs these narratives and gives them meaning (while clearly not “white”) still feels oppressively American. Then again, I happen to be more interested in what it means to be a contemporary Arab-Muslim independently of the West than in how to make the Arab component of American society more visible or agreeable to the mainstream, which is partly what Zeineddine seems to be attempting.

Just underneath the demitasses of Turkish coffee and the bowls of pumpkin seeds, I could see that his presuppositions about love, faith, and the good life owe more to consumer capitalism and liberal, “woke” morality than anything “Arab” or traditional. People’s lives are articulated in narrative and dramatic — not just linguistic — idioms that the average American can effortlessly understand.

In the American view, whether true or not, practically all Muslims are practicing believers, for example. And so there is only one character in the book who says he is an unbeliever, Zizou in “Zizou’s Voice.” In America, success means making money by providing the largest possible number of people with a commodity they desire — something you achieve by developing your product, finding your target market and showing pragmatic rather than principled initiative. And so Zizou finds fulfillment not as a fantasy writer — his true passion — but as a voice actor. Why? Because a former friend of his who has been a reborn believer recruits him to recite the Quran — in English, though he has to put on an Arab accent — for a best-selling album he produces.

Zeineddine’s prose is eminently engaging. Yet I confess that, in making my way through Dearborn, I found myself longing for the immigrants in Hanif Kureishi’s work. Kureishi’s characters too are Muslims in an English-speaking environment, but their identity fuels transgression rather than conformity. They rebel against both their ancestral traditions and the lowest common denominator of their immediate surroundings. Even when they decide to embrace their heritage, they end up demonstrating how impossible that is by turning into full-blown radicals. Not so the Dearbornites.

In the opening story, “The Actors of Dearborn” — in fact a version of this happens in “Money Chickens” too — Arabs who have been in America for decades and never once thought of signaling their belonging suddenly start changing the way they dress or talk, in order to appear as all-American as possible. They do this because 9/11 has left them terrified of being deported or persecuted. Their desperation is touching, but the way they flaunt an obviously fake patriotism is risible, as Zeineddine no doubt intends it to be, and the result is both compelling and outrageous.

All through the book, Zeineddine walks a fine line between pathos and hilarity, balancing laugh-out-loud one-liners with moments of heart-rending melancholy. But since the stories don’t get into the psychological complexity of his characters, what they do feels more like opportunism and hypocrisy than anything. This makes them not so much unsympathetic as unremarkable representatives of Arabness, and while it may be intended to humanize and demystify a potentially problematic identity, it also raises a question I’ve long considered: how should South immigrants live once they have reached the North? And, assuming there is any element of choice, from the viewpoint of the oppressed — not that of the anti immigration oppressor — why should they really be there in the first place?

There seem to be two models of equality at stake. One involves being integrated into a more or less homogeneous society of which you have the right to be a seamless part. The other consists of being cooped up in enclaves within a kind of federation of “cultures” where your prejudices can remain intact. Never mind that your outdated attitudes about women’s premarital virginity or mental health, say, are contested even in your country of origin — equality means that they be “respected” by the liberal West.

Again, this is not the author’s fault. Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia came out in 1990 — two years after Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, eleven before 9/11 — and in the last 30 years history has undoubtedly pushed the Muslim immigrant experience further and further away from the first model into the second. Without the conservative, taboo-laden atmosphere that suffuses these lives, Zeineddine’s stories would probably feel implausible.

No work of fiction can fully capture Arab identity in the US anyway. And whatever my reservations about the way identity comes through in Dearborn, it is also true that a topic and a subject are not the same thing. The Arab American community is Zeineddine’s stated topic. His subject, compellingly pursued in the grand tradition of Maupassant via O. Henry et al, is the state of humanity after the digital revolution. In this sense, no matter what you think of the Zeitgeist his work reflects, Zeineddine transcends it. Arab, not, or not really, here are true individuals seeking ways to express their identity against and across resistant geographic and cultural reference points.

In “Hiyam, LLC,” a Lebanese divorcée joins her immigrant son in Dearborn and ends up marrying a white man — she has him convert to Islam even though she knows he will neither believe nor practice the religion — and starts her own real estate business in defiance of the local Lebanese real estate tycoon.

In “Yusra,” a middle-aged butcher has lived his whole life as a violent alpha male when, with the help of the Internet — and unknown to anyone in the small patriarchal realm he has established in Dearborn — he finds a way to express his buried transgender identity.

In “Marseille,” a Druze survivor of the Titanic — and one of the earliest Arab immigrants to settle in Dearborn — tells the story of the 20-old husband she lost when the ship sank in 1912, 86 years earlier.

In “Rabbit Stew,” a mysterious uncle who arrives in Dearborn in 1991, soon after the end of the Lebanese Civil War, claims to have been a ruthless sniper in a militia, but it turns out he recoils at the sight of a rabbit bleeding.

Zeineddine casts as wide a net as he can, taking a broad and diverse perspective on his topic, and he subtly interlinks the stories, turning Dearborn in some sense into a collective mode of existence. But it is his eye for unusual, often surreal detail that enables him to construct unique narratives despite the overarching sense of an easily identifiable group with clear and predictable traits: a man hiding his cash savings inside frozen chickens (“Money Chicken”), a dead and possibly imaginary lover commemorated by the cooking of rabbit stew (“Rabbit Stew”), a girl who starts smoking at the age of seven to overcome her nosebleeds (“Marseille”). The plot lines are taut, but the stories remain open-ended, and regardless of how much time has elapsed — sometimes it is a few days, other times it is nearly a century — by the last line the protagonist will be in a different place.

“In Memoriam” is the story of Farah (whose name means “joy”), a young Lebanese American woman and practicing Muslim who dresses only in black, is interested only in death, and works as an obituary writer and copy editor at the local newspaper.

Farah has never been to Lebanon, her parents’ country, but nothing interests her more than the gatherings they organize in their basement or garage, where at some point each time fellow immigrants will start recounting tragic stories from “the old country.” When she tries to tell her own tragic stories about younger Dearbornites who have killed themselves or died of an overdose, Farah is no longer welcome at these gatherings. The older generation will only accept the lies that they tell each other to cover up what they perceive to be taboos. But Farah manages to find her way back into the fold by starting to make YouTube videos commemorating their and other Lebanese people’s dead loved ones.

In the end, however, Farah’s failure to make a life for herself, whether with the white American she falls in love with or anyone else, leaves her lonely and in despair. Her subtle journey from belonging to being cast out to finding a new way to belong — only to end up even more clueless than when she started — struck me as a brilliant metaphor not only for the Arab American experience but for the human condition itself. Tragedy lurks wherever we are, but Zeineddine reminds us that we can still marvel at it — and laugh.