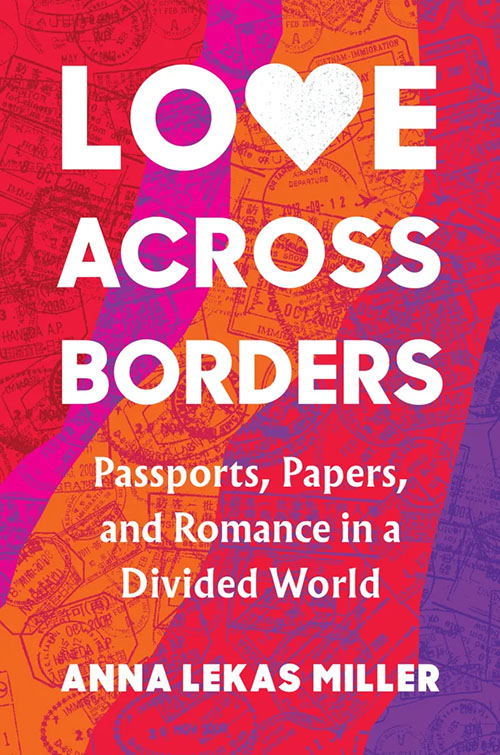

Lina Mounzer reviews the new book by Anna Lekas Miller that gathers stories of love- and border-challenged couples.

Love Across Borders: Passports, Papers and Romance in a Divided World by Anna Lekas-Miller

Algonquin/Hachette 2023

ISBN 9781643755229

Out of all the couples I’ve watched come together over these many years of my life, I can think of hardly any marriage — including my own — that wasn’t fundamentally entered into for the sake of papers.

This is not to say that these were loveless, passionless unions, or that the couples weren’t seriously committed to building a life together in all the ways that marriage implies. In fact, it was the seriousness of that commitment motivating the clear-eyed practicality of the decision. Because when you come from the Global South, or when you or your partner carry a passport that barely allows you to actually pass through any port (or airport), you are acutely aware of borders and how being unable to cross them together might affect your relationship. And you are also aware of the ways that passports and civil status might allow one person to “extend the accidental privileges and real protections of citizenship to the person that they love.”

This is the subject of Anna Lekas Miller’s book Love Across Borders — the way that global political forces can intervene into one’s most personal relationships, and how borders can inscribe themselves in the most intimate spaces of a person’s life. The book provides a wide overview of the history of passports and borders, the laws that govern them and how those laws came to be. But the information is built on the scaffolding of what is essentially a series of love stories, the principle one being that between Lekas Miller herself and her now-husband Salem Rizk, who first meet and fall in love on equal footing as fellow journalists in Istanbul, before a deportation order for Rizk upends their unfolding romance. Suddenly, they are forced to contend with all the heretofore invisible structural inequalities between them, which are, as Lekas Miller reminds us, “neither sexy nor romantic.” And so the American-born Lekas Miller and the Syrian Rizk go to Erbil, seemingly the only place on earth they can physically be together, frantically researching the bureaucratic possibilities in various countries in the hopes of finding a place where they can build a comfortable life.

“We are told,” writes Lekas Miller, “that love conquers all. What happens if you do not have the right kind of passport?” The book illustrates various answers to this question by taking us into the stories of a number of other couples, all struggling to reunite or be together in a world crisscrossed by merciless borders and mediated by ever-more merciless anti-immigration laws. Some of the stories are harrowing, involving actual life-and-death situations. In the story of Wala’a and Ahmed for example, Wala’a, a Syrian refugee seeking to leave Lebanon to be with her fiancé in Greece, is left with no choice but to board a dinghy bound for the European coast. The boat, as so many tragically have, capsizes on the way. Miraculously, Wala’a is the only survivor, rescued by the coast guard.

Then there are Oscar and Darwin, a young queer couple running from serious persecution in their native Honduras. They flee northward to seek asylum in the US, only to be apprehended and jailed in separate detention centers with no way of knowing one another’s whereabouts.

Wala’a felt doors closing. Ahmed sensed an opening.

“If I asked you to be my wife, would you come to Greece?”

And that is how she found herself making her way to the rickety fishing boat as it bobbed in the dark sea, wondering what it would be like to marry a man she was in love with but had never met. As she put one foot in front of the other, she realized she was stepping into the unknown in so many ways. Be brave, she told herself, slipping the life jacket over her head.

It would only take one wave to end her journey, but if she didn’t face that possibility, she would never discover the life that could be waiting for her on the other side. If she didn’t push through her fear, she might never learn the meaning of true courage—or for that matter, true love. If she didn’t challenge the borders meant to keep her in one place, she might never know what it feels like to break free.

The boat lurched forward as she stepped on board. There was no turning back.

Even as far back as medieval times, Lekas Miller tells us, the ancestor of the modern passport sought to control “the internal movement of poor people” rather than “the international movement of foreigners.” Over the years, laws came to enshrine — and compound — these attitudes further, with travel restrictions acting as a kind of “punishment” for Global South countries which sought independence from their former colonizers, who responded “by sealing their borders to their former subjects, requiring visas for them to work, immigrate, and in some cases even visit.” While Nigerians, for example, could once “freely travel to work or study in the United Kingdom” while their country was still “a British protectorate,” today the opportunity is reserved only for “those who are rich enough to be approved for visas.”

Thus, some people are forced to take cruel risks to seek different life circumstances, and, provided they make it safely to another country, they must then navigate endless red tape and bureaucracy to stay. And the situation is made even more complicated, and more risky, when trying to stay together as a couple or family.

While seemingly opposites, bureaucracy and love have long been entangled with, and are inseparable from, one another. Marriage has always been an extension (and tool) of the state, which benevolently allows the legal union of those it deems desirable and useful to the national project and conversely conspires to keep the wrong kinds of couples apart. But it can also be a way for those “wrong kinds of couples” to unite against the state, using conformity to the rules as a way of, not outright dismantling them (master’s tools; master’s house) but at least expanding who they might include. Thus, to take the example of the United States, mixed-race couples fought anti-miscegenation laws by the mere fact of their togetherness until the laws were abolished following the Supreme Court’s decision in Loving vs. Virginia; gay couples fought for marriage equality rights and (in some states) received them. In my own country, Lebanon, couples of mixed religion seek to confound sectarian civil status laws by exploiting certain (very narrow and difficult) loopholes.

But as the West puts its best face forward, crowing about its respect for individual freedoms, its other, truer face is that of increasingly draconian anti-immigration laws. Today, these have come to function as another way of enforcing a kind of anti-miscegenation, with family separation becoming common punishment, in the US, Europe, and Australia, for daring to migrate-while-poor-or-brown.

And so, while all the stories in Lekas Miller’s book have happy endings, in that the couples eventually find ways to be with one another, it is sometimes at great cost. Ava, an American who moves to rural Mexico with her young son to be with her deported husband José, finds eventually that they can’t afford their lives there unless she leaves every year for six months to work in the US. Cecilia, whose husband Hugo is also deported from the US — over an expired vehicle registration — must raise their five kids as a single parent, going alone periodically to Tijuana to visit with “the love of [her] life.” Other couples continue to live under the imminent threat of separation. Lekas Miller and her own husband remain unsure about their fates until Rizk is finally granted asylum in the UK, and she must ironically marry him to obtain the papers that will allow her to remain in the country.

Fundamentally, what makes Love Across Borders so compelling is how lovingly it is written. It is a book essentially about inequality that nevertheless reads like a romance novel in the best way. The love stories are rendered with such tenderness, with such kind attention to the small details of love — not just for the lover, but for family, for culture and country — that this alone serves to drive home the deeply unjust nature of the borders that separate our world.

Along the way, Lekas Miller asks us to contemplate a different kind of world. Not so much one without borders, but a world where the effort is instead focused on real “reparative justice […] the redistribution of resources, particularly given that so much migration is prompted by global inequality,” as Dr. Gurminder Bhambra, a professor of Postcolonial and Decolonial Studies at the University of Sussex tells Lekas Miller. The world described is somehow even more utopian than one where Fortress Europe and the rest of the Western enclaves open their doors to anyone and everyone wishing to enter. The real key, says Dr. Bhambra, “would be to make places more livable so that people didn’t feel like they had to move to live more fulfilling lives.”

Anyone who has been forced to leave their country — or even to contemplate leaving — for “a better life abroad” knows the agony of such a choice, of having to say wrenching goodbyes to the people and places one loves. Which only serves to further the humiliation of how difficult Western countries — often the same countries that colonized and exploited yours — make it to go abroad.

And so what is at stake here is even bigger than the desire for freedom of movement, the ability to adventure the world unencumbered by borders and those who enforce them. It is rather the ability to live a dignified life wherever one chooses, especially that people’s first choice, as the book makes clear, would often be not to have to leave home. This is a truth I know well. Had this region been more stable, for example, my own parents would not have left Lebanon in the 1980s; we wouldn’t have had, or needed, to attain a second, better passport; I wouldn’t be currently weighing the costs (such costs, emotional and material both) and benefits of being forced to leave my country again now, and worrying over how to take my undesirable-passported husband with me.

Like all the most immersive romance stories allow you to do, by the end, Love Across Borders had me sighing over deliciously agonizing what-ifs and if-onlys. Imagining a utopia blessed by the open acceptance of love. But here the utopia is a place where you are free not just to love who you want with dignity and pride, but where you want. In a world currently cast in the lurid light of the genocide on Gaza, such dreams seem farther than ever. But what is love if not the fundamental uniting force in a divided world?