Almost as soon as the Hirak mass protest movement erupted in 2019, the Algerian government began to methodically target activists, journalists, and artists, as well as citizens regarded as too outspoken. Six years later, an atmosphere of fear and silence still hangs heavy over the country.

On September 9, 2019, lawyer and human rights activist Salah Dabouz was walking down a poorly lit alley in the southern city of Ghardaïa when he was stabbed.

“I sensed someone walking behind me. I turned and saw a figure approaching. At first, I thought it was someone who needed information. I walked towards him then saw him take out a knife. I saw fire between my eyes when he stabbed me, I fell to the ground, screaming. He fled on a motorbike with someone else who was waiting. If it hadn’t been for the miraculous arrival of some young people emerging from a nearby mosque, I don’t think I would have survived that night,” he recalls.

From 2013 to 2018, Dabouz was the president of the Algerian League for the Defense of Human Rights (LADDH), the regime’s bête noire and one of the few impactful opposition organizations in the country. Dabouz, who vocally denounced the regime’s human rights violations and defended prisoners of conscience, progressively became a political target.

That pressure only increased once he displayed his open support for the Hirak pro-democracy movement, which, beginning on February 22, 2019, rather astonishingly drew tens of thousands of Algerians to the streets in numerous cities to demand the resignation of President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. Despite the president’s eventual resignation, in April, protesters continued to call for regime change. While there had already been social movements in Algeria, often in the form of riots or demonstrations specific to certain professions (or conversely, the unemployed), this sudden vocal increase in public political engagement and, more importantly, its peaceful expression, sent shock waves through the nation’s political and military establishment and even more so, Algerian society. This time, protesters weren’t merely responding to a specific political or social crisis. They were demanding that all the country’s leaders step down — even daring to openly address military leaders in their slogans — and thereby threatening the decades-long accepted political order.

In the midst of this public movement, in the course of 2019, Dabouz was placed under judicial control on two occasions, which entailed three check-ins per week at a court in Ghardaïa, 600 kilometers from his office in Algiers. Of course, this obligation made it impossible for him to do his job.

“I tried to adapt to and resist this harassment. It started in 2012 then increased in 2019. The most serious incident was when I received a threat on June 27, 2019 as I left the Ghardaïa court, just after signing in for my judicial control. A person I do not know threatened physical violence if I didn’t stop making statements against ‘certain officials.’ This prompted me to immediately file a complaint at the Ghardaïa court. But there was never any follow-up,” he explains.

Only a few months later, Dabouz was stabbed in that alleyway. One week later, he left the country. He told me, “I realized that not only was my freedom at risk, so was my life.” He has since been living in exile in Belgium, where he is now the director of L’Observatoire des droits et libertés pour l’Afrique du Nord (The Observatory of Rights and Freedoms for North Africa). Dabouz says that he doesn’t plan on returning to his home country anytime soon.

Algeria during and after Hirak

The repression of the Hirak movement, which has been unique in terms of both intensity and duration, was almost immediate — intimidation efforts and cursory arrests accompanied the first sit-ins and demonstrations. The government crackdown gradually intensified following President Bouteflika’s resignation in April 2019, in an attempt to restore institutional stability. Demonstrations persisted, however, until the Covid pandemic forced a year-long lull. Then, in February 2021, they abruptly resumed, albeit in smaller numbers. The government crackdown resumed as well, and was particularly efficient this time. A few months later, the movement had ceased entirely. Protests stopped and remaining dissidents as well as citizens critical of the regime found refuge on the Internet. By June 2021, the protesters had disappeared from the streets. And yet, over four years later, government repression is even worse now, as journalist Mustapha Bendjama notes:

“[Before] there was noise, there was the international press, NGOs applying pressure. But four years after the Hirak [when I was jailed], people had lost interest in what was happening in Algeria and in this crackdown. And the authorities began to have their hands a little freer and to repress more easily.”

Since 2019, Bendjama has been detained on so many occasions that he admits he has lost count. At first, he believed that his various summons and arrests, which he estimates at over 40, were mere formalities, that is until his incarceration in February 2023.

“I was among the first people targeted from the very beginning of the repression. I was arrested often, almost each Friday [the day of the weekly national demonstrations]. I’d find myself at the police station for the entire day, unable to cover the important events happening in front of me,” he says.

“Afterwards, I endured judicial harassment. I spent more time in police stations and courtrooms than in a newsroom or in the field. We [journalists] are unable to do quality work when we spend most of our time in police stations and courts. Not to mention the fact that mentally we are less focused on work and more on our [legal and judicial] problems, which we must resolve, [given] the repercussions on our personal and professional lives, which doesn’t leave much room for the concentration, resources or energy required to do the work of a journalist properly.”

According to human rights activist and former detainee Zaki Hannache, who has closely documented the repression within the country and now from his exile in Canada, at least 1,350 people have been jailed for politically related motives since the Hirak began (including 51 this year).

After fourteen months in jail, Bendjama, now labeled as both a dissident and a former detainee, encountered a new difficulty: finding employment within a media sphere deeply restricted by the crackdown. He is also still arbitrarily banned from leaving the country and has been detained on several occasions upon attempting to cross the border to Tunisia.

Bendjama’s story is sadly emblematic. State repression has affected journalists, members of political parties, civil society activists, university students, professors, artists, and lawyers, even Algerians involved in the Hirak in the diaspora, some of whom have been sentenced in absentia or had their families subjected to regime pressure. Across the country, arrests — and releases — are so frequent that it has proven impossible to keep precise count. In the lead-up to the presidential elections of September 2024, one of the few reliable sources of information on political detentions, the Facebook page of The National Committee for the Liberation of Detainees (CNLD), created in 2019, was closed by one of its authors without any official explanation.

According to human rights activist and former detainee Zaki Hannache, who has closely documented the repression within the country and now from his exile in Canada, at least 1,350 people have been jailed for politically related motives since the Hirak began (including 51 this year). That number is likely larger, however. Dozens of activists and protesters have been repeatedly detained and judicially harassed, with many charged in multiple cases, and trials of activists, protesters and journalists have become commonplace. Hannache also reports that there are currently 238 prisoners of conscience. As more and more activists are silenced, lawyers have emerged as the primary if not sole outspoken defenders of political detainees. They have essentially replaced the local media, taking over the daily online announcements of detentions.

A climate of silence and fear

Though open debate flourished in the wake of the Hirak, Algerian citizens appear to have since shelved, or perhaps merely closeted, that unprecedented engagement in political affairs. According to local activists, public debates and more generally, political expression have ceased entirely. In many aspects, free speech is more restricted than it was during the Black Decade of the 1990s, whose spectacular toll — an estimated 200,000 deaths and the disappearance of tens of thousands — still didn’t prevent heated public debates and crowded rallies.

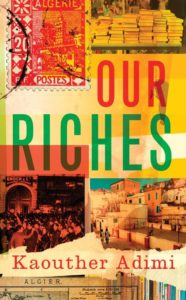

The same dampening has impacted the country’s cultural scene, especially vibrant during the Hirak, with painters, cartoonists, and musicians supporting the demonstrations. They too were targeted by the ensuing crackdown, which shut down venues of free expression, notably cultural organizations, and stifled literary production. In April 2023, for example, in Aokas, a town in Kabylie, a renowned literary café that had hosted debates with artists and intellectual figures for years, was closed by court decision. That same year, and again in 2024, Koukou Editions was banned from the Salon International du livre (SILA), an annual book fair. Also in 2024, literary repression expanded further afield; this time, the target was long-established French publishing house, Gallimard Editions, which was banned from attending the SILA, after publishing Houris, a controversial novel about the Black Decade – a topic that remains taboo in Algeria — by journalist and author Kamel Daoud.

Post-Hirak, the independent press in Algeria has also withered. Since 2019, at least 70 journalists and other media workers have been arrested. Based on my own numbers, drawing on reports of in-country detentions, 25 of them have been jailed, including Adelwakil Blamm and French journalist Christophe Gleize, currently incarcerated. Several prominent newspapers, including previously outspoken El Watan, as well as news sites such as Tout sur l’Algérie (TSA), have adopted a pro-regime editorial line. The final nail in the coffin was the shutdown in December 2023 of Radio M, one of the few remaining independent outlets which gave a voice to critical and opposition figures, along with the incarceration of its editor Ihsane El Kadi.

In Kabylie, a region known for its tense relations with Algiers, local activists and reporters have been especially targeted, even in instances of seemingly non-political issues. In Amizour and Tala Hamza, two villages in the Bejaia region where authorities decided to exploit lead and zinc in 2023 despite public opposition, locals I interviewed — most off the record — describe an “atmosphere of terror,” namely intimidation and threats made to those who organized meetings and signed petitions to protect their land and agricultural resources.

Censorship is widespread, and largely online. Even a seemingly innocuous online campaign calling for political reform, in December 2024 — #مانيش_راضي [#I am not satisfied] — drew the ire of the regime. According to Detenus d’Opinion, a Facebook group and one of the few remaining spaces to give some visibility about ongoing detentions, 28 people were arrested in the wake of the campaign, and 21 incarcerated, including activist Mohamed Tadjadit, known as the “poet of the Casbah.”

Perhaps the most damaging consequence of the post-Hirak crackdown is the resulting self-censorship. Several of my sources admitted as much in interviews, noting that self-censorship is a major obstacle to the fulfillment of their professional commitments as well as to simply being able to make a living.

“We are much more careful in the exercise of our profession. If we believe that information must be disclosed, we encounter many obstacles in doing so: the lack of official communication, of sources. News sources are becoming more and more afraid. No one wants to talk to journalists anymore for fear of being accused or prosecuted for fake news,” says Bendjama.

Bendjama’s story is sadly emblematic. State repression has affected journalists, members of political parties, civil society activists, university students, professors, artists, and lawyers, even Algerians involved in the Hirak in the diaspora, some of whom have been sentenced in absentia or had their families subjected to regime pressure. Across the country, arrests — and releases — are so frequent that it has proven impossible to keep precise count.

Nowadays even dissidents who are not facing charges prefer not to take the risk of entering Algeria for fear of being detained. Several, including writer Boualem Sensal, who is currently in detention, have been arrested after returning for holidays or to spend time with their loved ones, without being informed of potential or pending charges. In many cases, their families in Algeria have been subjected to intimidation efforts.

In order to follow the political situation, ordinary Algerians critical of the regime have turned to online news networks such as Al Magharibia, or YouTube channels created by regime critics outside of Algeria, including Hicham Aboud and Abdou Semmar, who have endured intense intimidation.

Rabah Moulla, a member of the Social Workers’ Party (PST) in his youth, participated in solidarity Hirak protests in Quebec, where he’s been living since 2006. In 2020, he and a group of friends launched the YouTube channel AlternaTV, one of the rare spaces in which the opposition has been able to exchange. In an interview, he told me he has been targeted online by government agents in attempts to discredit him.

“Alternatv was created by progressives and democrats. The government therefore can’t raise the specter of the Islamist menace. [The channel] is also an inconvenience [to the regime] because of the [range] of its programs and guests: Intellectuals, journalists, trade unionists, political and cultural figures, feminists, sociologists. The authorities activated their networks to attack AlternaTV and myself. The regime’s YouTuber agents dedicated some ten videos to us [to discredit us] as well as numerous articles on sites reputed to be close to the intelligence services,” he says.

Back in Algeria, public gatherings and political meetings have become increasingly difficult to organize; there are currently no organized demonstrations or sit-ins in the country, not even in support of the Palestinian cause. Opposition parties and human rights and cultural organizations have been banned by obedient courts controlled by the regime. For the few organizations which continue to exist, administrative pressures have been relentless, preventing their members from organizing public conferences, holding committee meetings at their headquarters, or inviting speakers. In a video posted online, Abdelkrim Zeghileche, a former member of the Union for Change and Progress party (UCP) who has been repeatedly jailed, recounted the difficulties he was facing when trying to set up events for the party. He claimed a local official had told him that a public room would be unavailable “Ila al abad” — forever.

Legislation has been weaponized as well, beginning with the adoption of new laws during the pandemic, and the amendment of Article 87 bis, which narrowed the definition of terrorism and enabled the jailing of hundreds of people.

Clearly, even in the absence of demonstrations and organized political opposition, the government in Algeria continues to stifle the slightest expression of dissent. Although the regime hasn’t resorted to violence as it did in previous mobilizations such as the 1988 uprisings or the Black Spring in 2001, it has effectively extinguished the nascent democratic culture and political engagement kindled by the Hirak. Dissidents are still being arrested, and free speech — be it artistic, literary, journalistic, or political — is quashed. The danger is that what could have been perceived, at least in the beginning, as a transient crackdown on a specific movement is looking more like an enduring attack on freedom of expression.