<

<

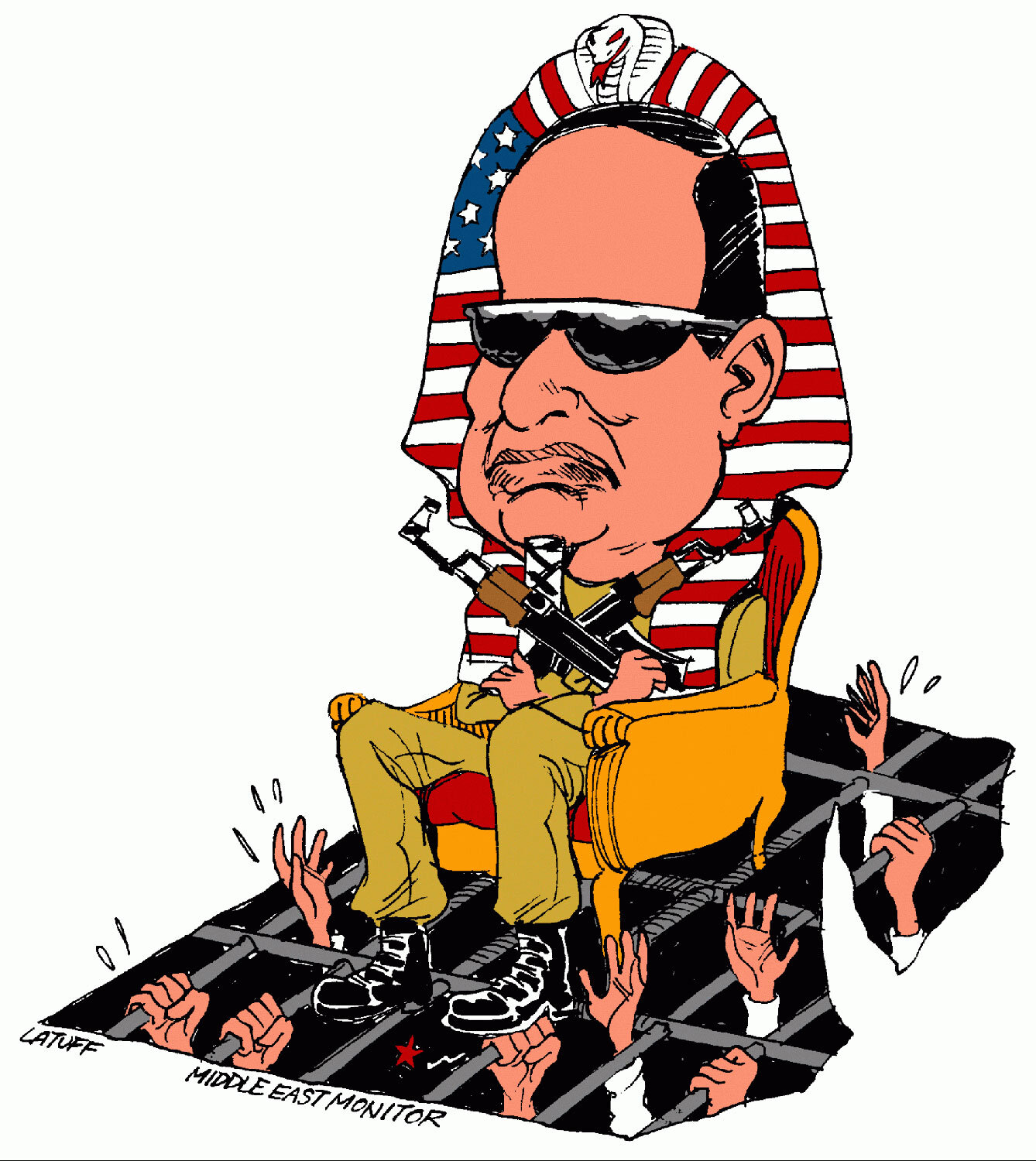

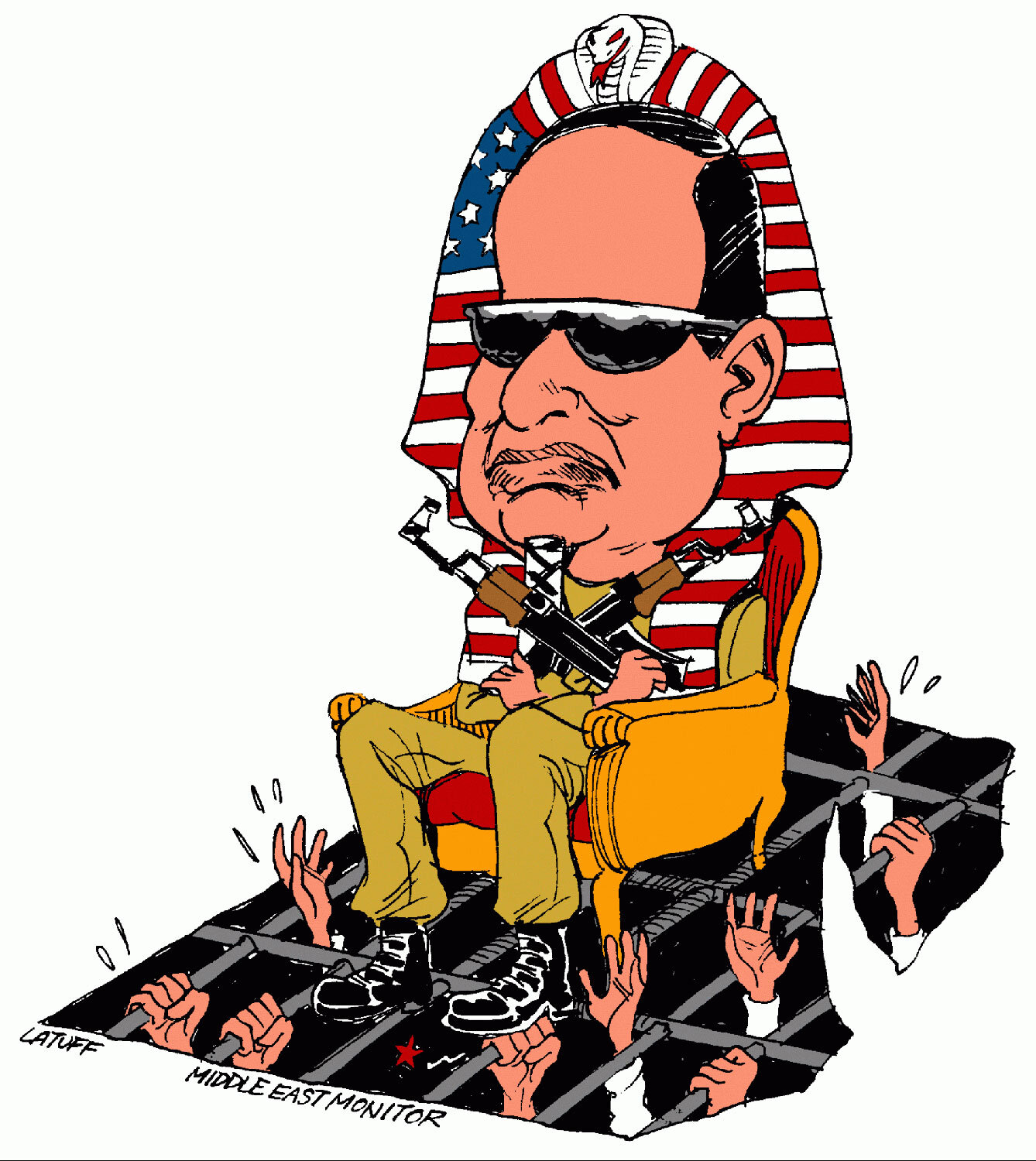

Latuff’s caricature of Egypt’s president, Abdelfattah el-Sisi.

Monique El-Faizy

It’s easy to dismiss Donald Trump’s anti-press rhetoric as simply more bloviating on his part, but when the putative leader of the free world employs the rhetoric of dictators against the institution whose mission it is to hold elected officials accountable, he is sending a clear message. If press freedom is not to be valued in the nation that holds itself up as an exemplar of democracy, why should it be in more oppressive quarters?

It certainly hasn’t been in Egypt. I remember the optimism with which the new constitution was greeted in January 2014, guaranteeing, as it did, a free press and other civil liberties. But those hopes were quickly dashed; the crackdown on dissent that began in the wake of the August 2013 coup that ousted President Mohamed Morsi, during which 16,000 people were thrown in prison, slowed briefly but was ultimately unhindered by the newly minted constitutional guarantees.

The same month the constitution was adopted, police detained an Egyptian filmmaker, Hossam al-Meneai, and his American translator, Jeremy Hodge. Hodge was quickly released, but al-Meneai was held for 18 days and tortured. That February, a Yemeni blogger was arrested after conducting interviews at the Cairo Book Fair. While journalists made up just one category on a long list of people getting caught up in dragnets at the time—supporters of Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood being at the top—it was clear that not touting the official line, which many in the press did with little prompting, put one in jeopardy.

The risks have but grown since then. According to Reporters Without Borders, nearly 90 journalists have been put in prison in Egypt since January 2014. That’s in addition to the growing number of people who have been jailed for offenses as minor as tweeting criticism of the government.

Anti-regime protests in September 2019 ushered in a new round of arrests, with more than 4,000 people being detained, including at least 20 journalists, according to Reporters Without Borders.

The Covid-19 crisis hasn’t done anything to slow the packing of Egyptian prisons, which have long had notoriously deplorable sanitary conditions. On the contrary: the pandemic has given the regime shade to launch yet another clampdown, using a weapon in its arsenal of press-silencing weapons that was minted in 2015 with the passage of a broad counterterrorism law. Journalists now are routinely charged with spreading false news, misusing social media, or engaging in terrorism.

Those charges were leveled against journalist Ahmad Allam, who was arrested at his home in April, as well as against journalist Haisam Hasan Mahgoub in May. In June, 65-year-old Mohamed Monir was arrested on similar charges after writing a column criticizing the government’s handling of the pandemic. He died the following month after contracting Covid-19 in detention. Also detained in June was filmmaker and writer Sanna Seif (b.1993) who according to PEN International was arrested “for investigation for offenses including ‘false news’ and ‘terrorism’. Her detention is related to her activism on behalf of her imprisoned brother, Alaa Abd El Fattah, and for other political prisoners.” And journalists Hany Greisha and El-Sayed Shehta were detained in August, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists; Shehta was Covid positive and after collapsing in the police station had to be taken to an intensive-care unit, where he was shackled to a hospital bed.

Clamping down on protest speech during the pandemic creates a potential for catastrophe. As Juan Cole noted in a column for Democracy in Exile on Oct.2, “Locking up and mistreating Alaa Abd-El Fattah, Mohammed el-Baqer, al Jazeera journalist Mahmoud Hussein, human rights defender Bahey El-Din Hassan, and tens of thousands of other independent voices of conscience in Egypt’s brutally mismanaged prison system during the coronavirus pandemic is a potential death sentence.”

“There have been so many waves of crackdowns on journalists in Egypt, but this one seems like the worst,” Sherif Mansour, Middle East and North Africa coordinator at the Committee to Protect Journalists, told the Washington Post in July. “The number of journalists in jail has been steadily rising. Since March, at least nine more journalists have been arrested. All of them specifically for their Covid coverage.”

The pace of detentions has continued. In mid-September, journalist Islam el-Kalhy was arrested and charged with disseminating fake news after reporting on the death of a man in police custody. And on October 3, freelance journalist Basma Mostafa was detained when she arrived in Luxor to report on the death of a young man there during a police raid. She, too, was given the standard array of charges of spreading false news, misusing social media and joining a terrorist organization, and remanded to jail. Mostafa was released a few days later after an international outcry.

Exiled comedian Bassem Youssef’s Revolution for Dummies.

Those who weren’t arrested have been forced into exile, including Tahrir Square rocker Ramy Essam, cardiologist and hit comedian Bassem Youssef, and a number of rights activists such as Bahey eldin Hassan, with whom we speak in this issue, and who, like others, was tried and convicted in absentia, making a return to their homeland all but impossible.

Manifestly, President Abdel Fatah el-Sisi needed no encouragement in his dictatorial tendencies, and from the get-go he showed that he felt no particular need to bow to democratic norms. (When Sisi was elected president in May 2014, he won an eyebrow-raising 96.91 percent of the vote. By way of comparison, when I was living in Moscow during the waning years of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev won that nation’s first and only presidential election—in which he ran unopposed—with a comparatively paltry 72.9 percent of the vote.)

Sisi’s brutal crackdown on dissent is one of the most severe in the world. “The press freedom situation is becoming more and more alarming in Egypt,” Reporters Without Borders, laments, ranking Egypt 166th out of 180 countries in 2020, a drop of three rungs from the previous year (Saudi Arabia is 170 and Iran is 173). The country is the third worst jailer of journalists, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

While Sisi didn’t need Trump’s permission to engage in such heavy-handed tactics, which began during the Obama administration, Trump has actively encouraged Sisi’s authoritarian approach. In April 2019, just a week before Egypt held a referendum to make changes to the constitution that extended Sisi’s term in office, increased the power the president has over the judiciary and further enshrined the role of the military in government, Trump hosted Sisi in the Oval Office and praised him as “a great president.” A few months later he referred to Sisi as his “favorite dictator.”

The two certainly seem to have found common ground in their treatment of the press. Of course, American journalists aren’t being jailed at the same rate they are in Egypt, but in cultural context, the assault on the profession in the US is no less shocking. The US Press Freedom Tracker counts at least 320 violations of press freedom since protests against police brutality broke out in late May; that number includes 210 attacks and 68 arrests. Many of the journalists were beaten by police and pepper sprayed.

“I believe that President Trump is engaged in the most direct sustained assault on freedom of the press in our history,” Fox News anchor Chris Wallace said at an event for the Society of Professional Journalists last December.

Trump’s record on civic rights has been poor as well. The Trump administration has eroded minority voting rights, weakened protections against employment discrimination and spousal abuse, turned back efforts to increase the number of minority students who to go college and has encouraged police violence.

All that sends a signal. So does Trump’s constant accusation of “fake news” and his declaring the press—which the founding fathers of the United States deemed essential to a functioning democracy—to be “an enemy of the state,” using a phrase more commonly emanating from the mouths of dictators. It lets leaders everywhere know that their oppression of the Fourth Estate is not only acceptable but, in Trump’s view, warranted.

In attacking the media, Trump has “effectively given foreign leaders permission to do the same with their countries’ journalists and even given them the vocabulary with which to do it,” New York Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger wrote in an op-ed last September. He said a Times investigation found that in recent years more than 50 government leaders had used the term “fake news” to justify anti-press activity, including Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, all of whom have been trampling roughshod over civil society in their respective countries. (Need we be reminded that Trump has effusely praised each of these strongmen?)

David Kaye, the outgoing UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, said in July that there had been a clear “Trump effect” on global press freedoms, which he characterized as “very negative.”

We must hope—and demand—that the next US President undo the damage done to press freedoms and call for global reform. Barring that, it is up to the dwindling number of countries who uphold civic liberties to step up and insist that these repressive regimes do better. If we have learned little else from the past four years it is that the words leaders use matter, and they resonate far beyond the borders of their own countries.

<

TMR contributing editor Monique El-Faizy is a journalist and author based in Paris.

<

<