The meta narrative behind Frank Herbert’s legendary sci-fi trilogy Dune foresees the modern-day disaster of never-ending colonialism and a planet destroyed by oil.

I grew up reading science fiction — in Arabic — from an early age, eventually becoming a science fiction writer myself. However, it wasn’t until I migrated to the U.S. six years ago that I was introduced to Frank Herbert. Although most of the science fiction classics of his time were translated into Arabic, Herbert’s works didn’t make it into Arabic until six years ago. Could this delay have been due to the controversial nature of his intertwining Islamic mythology with Arabic terms? Or was it the high cost of acquiring translation rights for a bestselling novel?

Dune as Sunnie’s sword

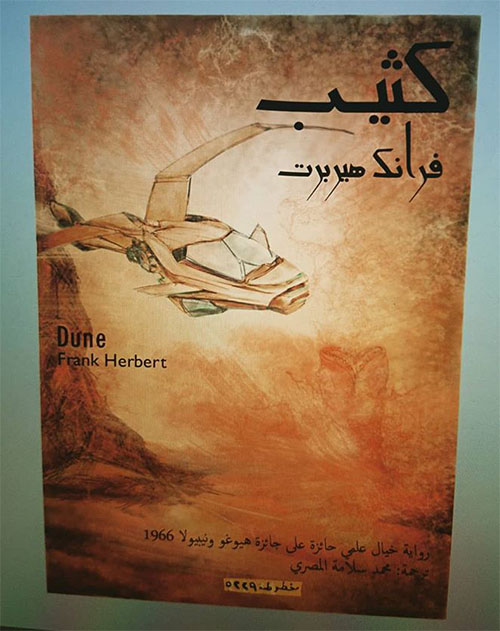

I recently read the first three books of Dune in English and watched the film adaptations. When I looked for the Arabic translations, I found two versions released in recent years. One is a paperback with the same cover as the English edition, translated by Nader Osama and published in 2021 by Kalemat Publishing. The other is available only online, translated by Mohamed Salama El-Masry and published by Makhatot in 2018. This version is accessible on Amazon Kindle and for free through the Internet Archive and several other online forums.

Intrigued, I downloaded this Arabic translation. The translator’s introduction examines Frank Herbert’s legacy, highlighting how his style and writing differ from American authors such as Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury, who were introduced to Arabic readers decades ago. El-Masry also discusses the technical choices he had to make, particularly regarding Herbert’s use of Arabic and quasi-Arabic terms. The introduction concludes with the translator’s heartfelt note of gratitude to his mother, who cared for him for four months and endured his discussions about the translation’s editorial details while he worked on rendering the novel’s 501 pages into Arabic.

I searched the internet for this translator but couldn’t find much. I asked friends, translators, and publishers if they knew him or had contact with him but received no answer. Finally, I stumbled upon a rabbit hole on Reddit where he was answering questions from Dune fans, especially Americans who were excited about an Arabic translation of Dune. His profile on Reddit showed a little activity, though I found several old posts where he expressed concerns about the other Dune translations, accusing them of using terms borrowed from his translation without mentioning him. I contacted Salama through Reddit, asking him all my questions. To my surprise, he began our conversation by saying, “A quick glance at our comments reveals that we have very different worldviews 🙂 I’m practically a Salafist, with ‘reactionary,’ conservative, and anti-progressive attitudes/opinions, while you are obviously too liberal (& too political) for my taste.”

Later in the conversation, when I asked him why he chose to translate Dune, he explained that he had been reading about Shia history in North Africa, specifically how they employed deception to conquer and colonize Egypt. He found striking similarities between their methods and the techniques of the Bene Gesserit in Herbert’s novel. In his translation, he emphasizes this point, offering the Arabic reader his Salafist interpretation of Dune, explaining that in the novel, the Bene Gesserit are witches who conspire against everyone in their pursuit to fulfill a prophecy of bringing forth the Messiah.

This was a lot to digest. It was the first time I encountered someone describing the Fatimid rule of Egypt — they were the ones who built Cairo in 969 — as colonization. His choice of words revealed a perspective deeply rooted in Salafi, ultra-Sunni ideology, with a pronounced opposition to Shia beliefs. It seemed as though his translation was part of a broader endeavor to combat Shia doctrines, aiming to expose their purportedly dubious techniques and heretical teachings.

Salama explained that the concept of the Mahdi, essential in Dune, is fundamentally a Shia concept. In the novel, the Mahdi (Paul Atreides) leads the Fremen to defeat the Harkonnens and the Empire but ultimately becomes a dictator, causing universal suffering. Salama’s translation, freely available on Internet Archive, includes a lengthy introduction, several annexes, and numerous comments. For instance, he adds a footnote suggesting that a dialogue between two characters was inspired by a specific line in the Quran.

In our Reddit exchanges, Salama told me he was paid for his translation by Makhtot Publishing House, which bought the digital rights from Herbert’s estate. For years, it was sold on Amazon Kindle for $2. However, he wasn’t satisfied with the publisher’s decision to cut some of his footnotes and annexes. Consequently, he published a full, uncut edition online for free, followed by an annex detailing how other translations had copied his work.

Many articles and literary studies have been published about Dune, analyzing it through the lens of Orientalism and post-colonial theory. Most of these studies were written by Western scholars and writers, who often view Shia and Sunni as a single entity representing the “Orient.” Their interpretations are captivated by the dramatic narrative of colonization and resistance, oppression and the oppressed, reflecting the American empire’s post-WWII view of the Gulf region. However, works of art have multiple lives and faces, and some might not recognize each other. How would a subaltern from the world of “desert” interpret the novel? And how would a work like Dune be influenced by the new Arab Gulf identity that is shaping the current Arab world?

The Trilogy’s Resurrection in 2024

Dune is not just a novel trilogy; it’s a franchise, an imaginary world first created by Frank Herbert and then continued by his son, who inherited and expanded the series. This American literary trend — where a writer’s legacy is carried on by his sons is in stark contrast to the Arabic literary tradition, where even if a writer’s son becomes a writer, he will strive to distinguish himself from his father’s work. What is considered shameless in one literary tradition is the norm in another.

This capitalist franchise nature of Dune is also what has given it its longevity. As it became a business, it was first adapted into cinema by David Lynch in 1984. While I enjoyed watching it, it’s the only Lynch film I don’t recommend. The Dune franchise was reborn with the recent two-film adaptation directed by Canadian director Denis Villeneuve.

The latest installment, Dune: Part Two, captivated global audiences due to its interaction with present-day geopolitics. In the film, we see scenes of the colonizing force, led by Baron Harkonnen, dispatching spacecraft bristling with weaponry to wipe out the homes and mountain retreats of the Fremen. The imagery is bleak — children drenched in blood, a woman mourning her family lost beneath the debris. These scenes eerily mirror the current images coming from Gaza, where colonial powers continue their genocide and exploitation as part of their regular business.

The film is full of such junctions; The Harkonnens calling the Fremen “rats” echoes the real-world rhetoric where the Israeli Defense Minister calls the Palestinians “human animals,” and then we see in the French publication Libération, a cartoon mocking starving Palestinian kids, depicting them haunting rats as food for Ramadan. Is art inspired by reality, or is reality shaped by art? The answer may be buried in the history.

The Seven Pillars of Wisdom

Approximately 100 years ago, a young agent by the name of T.E. Lawrence was deployed in Egypt as part of the British intelligence unit. He was disguised as an archaeologist, digging for antiques while also drawing maps for the British army in their preparation for war against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War.

In an orchestrated maneuver that would forever alter the fabric of Middle Eastern geopolitics, T.E. Lawrence was dispatched to Mecca. His mission was to persuade Sharif Hussein to rally the Arab tribes in Hijaz against the Ottoman Empire. In exchange, Sharif Hussein sought sovereignty over the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Syria, and Iraq — territories he envisioned unified under the banner of an Arab Kingdom, a forlorn dream that would be the seed of what is now known as Arab nationalism. With a mix of persuasion and deceptive promises, Lawrence ignited the flames of an Arab revolution. This vision of a consolidated Arab state catalyzed a seismic rebellion against the collapsed Ottoman Empire. Under the leadership of Faisal, son of Sharif Hussein, with Lawrence at his side, a formidable campaign unfolded, marking a pivotal chapter in the quest for Arab self-determination.

In the aftermath of World War I, Faisal found himself amidst the political machinations of the Paris Peace Conference. It was there, in the grand halls of diplomacy, that he confronted a harsh betrayal: British promises dissolved before his eyes as the British announced their plan to give Palestine to the Zionists and Syria to France. Faisal refused to “affix his name to a document assigning Palestine to the Zionists and Syria to foreigners.” The British shifted their support to Abdulaziz Ibn Saud, spurring him to challenge the Hashemite rule. What ensued was a series of fierce conflicts across the Arabian Peninsula, battles that raged for years. These confrontations culminated in the unification of the region, heralding the birth of what is today known as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Dune is not a straightforward champion of anti-colonial sentiment but is a complex exploration of the interplay between colonial power dynamics, indigenous resistance, and the quest for autonomy.

Meanwhile, Lawrence went back to London, and wrote his book The Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926) — a memoir that would become a bestseller and later inspire the epic film Lawrence of Arabia in 1962. This movie, with its sweeping desert vistas and intricate political drama, will appear as a ghost in the background of Dune’s books and recent films. For example, in the film, we see Lawrence trying to become an Arab by following all their traditions, yet ends up killing his friend Gasim, who committed a fatal mistake. Paul Atrides in Dune also will kill James to be accepted by the Freman. Many writers and even Herbart himself mentioned the shadow of Lawrence over the Dune world.

Dune is Lawrence’s dream, tracing his journey through an alternate narrative where the Arabian revolution might have thrived under a white man’s leadership. Frank Herbert amplifies Lawrence’s stereotype, infusing it with notions of Islamic theology and desert traditions. Paul Atreides, the protagonist of Dune, emerges from Lawrence’s aspirations and illusions, blending Western materialism with Eastern spirituality. In this imagined realm, the colonizer transcends his role, evolving into Emperor Paul Atreides.

Dune is not a straightforward champion of anti-colonial sentiment but is a complex exploration of the interplay between colonial power dynamics, indigenous resistance, and the quest for autonomy. It’s a narrative that compels readers to question the cost of progress and the ethics of dominion, encouraging a deeper reflection on our understanding of cultural homogeneity, resistance, and the right to self-determination in the face of universal exploitation.

In the golden days of yore, British colonialism often portrayed itself as a gentle force in contrast to other European powers. It critiqued practices like Belgium’s brutal regime in the Congo and Germany’s violent exploits in Africa, branding them as malevolent forms of colonialism. At the same time, they project their colonization as a scarification, a white man’s burden to lead other nations on the golden path toward the light; and that would be when the young independent nations often found themselves ensnared in a new form of dependency — this time, economic, woven into the fabric of a global trade network presided over by their former colonizers. Being a good colonizer, as the British or the Atreides house in the novel, does not mean you are anti-colonial, and we should not mix niceness with goodness.

Duke Leto Atreides receives the desert planet of Arrakis, also known as Dune, from the emperor. Seeing an opportunity to forge a strong alliance, he reaches out to the Fremen, the planet’s indigenous people, telling them they share a common enemy in the Harkonnens.

During World War II, the dynamics between the Allied and Axis powers influenced relationships worldwide. King Abd Aziz Saud’s alliance led to an attack from the Italian fascists that targeted American-operated oil refineries in Saudia and Bahrain. King Abdulaziz’s decision to align with the Allied powers, particularly the U.S. and the UK, was a strategic move that underscored the importance of Saudi oil/Melange /Spice in the war effort and beyond (Melange or “the spice,” a metaphor for Saudi oil, is the fictional psychedelic drug central to the Dune series).

In the web of Dune‘s power struggles, the Harkonnens and their imperial allies orchestrate the downfall of House Atreides, seizing control of the desert planet. Amid this betrayal, Paul Atreides, heir to House Atreides, survives but loses his father and kingdom, and flees into the desert with his mother. After a series of mystical experiences, he becomes Muad’Dib, adopts Freman name and gains an extraordinary foresight. Paul unites the Fremen under his leadership, igniting a jihad to reclaim his birthright and reshape the future. But unlike Lawrence, whose efforts were entwined with the complex politics of his time, Paul’s revolution triumphs. He confronts the emperor, compelling him to submit all power to him and marry his daughter.

On February 14, 1945, President Franklin D. Roosevelt met with King Abdulaziz ibn Al Saud aboard the USS Quincy, a heavy cruiser stationed in the Great Bitter Lake along the Suez Canal, Egypt. During this pivotal meeting, a historic agreement was forged between the U.S. and the Saudi Royal House. The Americans promise to provide security and protection for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, securing the stability of the Saudi ruling family. In return, Saudi Arabia agreed to supply the oil that America desperately needed to boost its post-war economy and to fuel the military fleets that would project American power across the globe’s oceans and skies. The Empire is addicted to Melange, and he who controls the spice controls the universe, said Frank Herbert.

The only disagreement that arose in this meeting was when Roosevelt proposed the establishment of an exclusive state for European Jews in Palestine. King Abdulaziz responded with unwavering firmness, stating, “The Jews should return to live in the lands from which they were expelled.” He added that the German oppressors should pay for the atrocities they committed and suggested the Rhineland as a suitable destination for European Jews.

In Dune Messiah, the series’ second book, Paul Atreides evolves into Muad’Dib, becoming the emperor of the universe. He is also known as Lisan al-Gaib and Mahdi. Paul’s Fremen warriors carried out a galactic Jihad, spreading his influence across countless worlds; more than 60 billion souls perished because of his Jihad war — in the recent movie they deliberately did not use jihad as it was presented in the novel. Muad’Dib canceled the government public services and established an authoritarian regime, relying on loyal administrators and military leaders, all this because he pursues a vision to guide humanity onto the Golden Path in the novel, and towards paradise in the films.

Dune was written in the 1960s, an era when hesitation grew around the liberation movement in Africa and other parts of the world. Postcolonial nations were struggling in civil wars, and dictators sometimes thought of themselves as leading humanity to the golden path. These pessimistic vibes run through the novel’s layers, creating a world where the right to liberation and dignity leads to an inevitable path of colonization and a jihad-ruled world.

Welcome to the Desert of the Real

In Dune, characters serve as symbols, chess pieces in a grand game of hegemony that Herbert maneuvers to reinforce his message repeatedly. The narrative suggests: No better future arises from revolt, jihad, or altering the stable power structure. No world can exist beyond the capitalist, algorithmic engineering realm.

For that, Dune characters speak primarily from their military or official roles, rarely expressing themselves as ordinary humans. Desire, dreams, and love — while present — are engines driving the characters toward one goal: power. That is why, in the novel, descriptions of technology and political gambits occupy significant portions of the narrative. The novels are incorporated with quotations from fictional history books and documents or passages from what is portrayed as the bible of Muad’Dib. These elements underscore the grand scale of Herbert’s universe, where personal feelings are often absorbed under the weight of broader themes like power dynamics, governance, and the march of history.

This design casts a heavy shadow over the novel’s prose and the story’s arc and pace. Reading a history book can be a pleasure, but infusing the narrative with this style turns the reading process into an experience of crossing a desert — except you arrive thirsty into a mirage. Every step, every page turned, brings you closer to an oasis that flashes with the promise of enlightenment — yet always seems just beyond reach.

From Dune to Neom

Growing up in Egypt, I witnessed how films that either misused Islamic motifs or stereotypically portrayed Arabs were often banned or edited to remove such content. However, times have evolved, and so has the cultural landscape. The latest Dune movie made its way into the cinemas in many Arab countries, including Saudi Arabia — a nation that had banned movie theaters altogether until a few years ago. This shift is symbolic of broader changes in the region. Situated near the Jordanian desert — a stone’s throw from where Dune was filmed — Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler, MBS, is leading the country toward his 2030 Vision that centered around building the new futuristic city of Neom. The city’s blueprint, as outlined on its website and through its promotions, reads like a page from a sci-fi novel: a genomic bank to monitor residents’ health, transportation facilitated by flying taxis, a society where robots replace human labor, the greening of the desert with skiing.

Yesterday’s Fremen did not merely adopt the colonizer’s model; they internalized it, letting it shape their dreams and ambitions. Paul Atreides, a futuristic figure inspired by T.E. Lawrence, is reborn, his legacy sparking a flame in the hearts of numerous Arab rulers. They do not dream anymore of one Arabian state or nation like the old Freman at Lawerence’s time, instead each one is indulged in a personal futuristic vision inspired from colonial science fiction work like Dune.

In Dune, Paul Atreides vows to the Fremen that he will transform their desert planet into a paradise, lush with towering trees and skies generous with rain. However, this grand promise stems from Paul’s own vision rather than the Fremen’s inherent aspirations. More critically, neither under Paul’s imperial reign nor in the envisioned future of Neom do the Fremen reclaim sovereignty over their oil/spice. Likewise, the wider universe remains shackled by its addiction to oil/spice, a dependency steering our planet toward global warming, destruction, and the grim prospect of transforming it into desert.

This narrative thread in Dune prompts a reflection on our world, where the pursuit of energy resources continues to fuel geopolitical clashes and environmental degradation, The novel’s premise is that it happened before and will happen again, so no need to resist or revolt. And this is what colonialization inevitably aspires to achieve: to crush even the idea that a better world exists, although a different path is possible — one that harmonizes with both the planet’s well-being and the genuine dreams of its inhabitants.

The most recent translation of the Dune into Arabic is Frank Herbert’s third novel, Children of Dune, by the translator Mohammed Naguib, published by Kalemat in 2024. Naguib has plans to translate the fourth novel God Emperor of Dune.

Anyone care to guess why the movie dropped the word “jihad” and glossed over the millions of deaths that followed the religious warriors? Too close to our actual future, as the events of October 7th proved, perhaps?

I believe we all know the answers to your questions. I want to point out that until the ’90s, the term “jihad” in English had a positive connotation, as it was then translated as “freedom fighter.” They were considered friends of America and were fighting the evil of red communism. In my opinion, the difficult question is not why they cut it from the film, but rather why Herbert used it in the novels, and how this reflects his typical patriotic American imperialistic mentality.

I read your article/analysis with great interest. Thank you, especially for your insight into Neom. One thing you didn’t mention. In addition to the Spice Melange being petroleum, the worm Shai Halud is all (giant) oil tanker ships which make it possible to fold space and travel vast distances so quickly. Was Herbert recommending hijacking oil tankers as a strategy?

It is remarkable to me that Dune had no Arabic translations until recently. I can only conclude that this was a multi-governmental decision recommended by numerous intelligence agencies. Was Dune really so dangerous?

That is a great note. Your interpretation of Shai Hulud is a smart way to identify it. Thank you for sharing it with us.

I don’t think “Dune” was dangerous. I believe it was translated late because its copyright is expensive, and Herbert and his son are greedy. In the end, “Dune” is their oil field that they control.

I think you’ve confused one thing — what ties all of Dune together is its refutation of the White Saviour. Paul is viewed as coopting the Fremen wish for freedom from oppression as a vehicle for his own schemes. It is not saying that seeking liberation is bad, but that liberation delivered by a colonizer is no liberation whatsoever. Paul is a colonizer embedding himself within Fremen culture. His “liberation” is merely reforming House Atriedes with a new powerbase, not the formation of a Fremen nation or identity.

You just describe the post-colonial states that exist now in most of Gulf States, which is the point of my article, thank you

Great article, thank you for this.

If it has not already been done, can I draw your attention to the ‘Sabres of Paradise’ Leslie Blanches book of the Russian invasion of the Caucasus in the 1850’s.

Herbert lifted huge amounts from it – Chakobsa, a Caucasian hunting language, becomes the language of a galactic diaspora in Herbert’s universe. Kanly, from a word for blood feud among the Islamic tribes of the Caucasus, signifies a vendetta between Dune’s great spacefaring dynasties. Kindjal, the personal weapon of the region’s Islamic warriors, becomes a knife favoured by Herbert’s techno-aristocrats.

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/the-secret-history-of-dune/