When it comes to nationality, we are richer for the diversity of our identities, and poorer for our divisions.

Uganda-born Zohran Mamdani is the mayor-elect of New York City. He’s married to Rama Duwaji, a Syrian American artist. He’s Muslim, he’s an immigrant, his parents are immigrants; under the Trump regime, immigrants have been hunted down and sent to prisons abroad; the immigrant is the Other, he has been criminalized. Mamdani’s election has inexorably altered perceptions, or at least changed the tenor of the conversation about immigrants and national identity.

We remember that immigrants made the Americas, from Canada to the tip of Argentina. Immigrants have made many countries; certainly have changed the way the country conceives of itself. Just think, Arabs occupied Sicily for two hundred years; Sicily has been occupied by Greeks, Romans, Vandals, and Vikings. How does the contemporary Sicilian conceive of her identity?

The Moors, of course, famously occupied the Iberian Peninsula, Spain and Portugal, for 800 years, during the reign of Al-Andalus. Imagine how that has inflected contemporary Spanish identity (Spaniards say “ojalá,” meaning I hope so, a dozen times a day, without remembering that it came from the Arabic and Islamic expression “inshallah”—if God wills it).

When it comes to thinking about nationality, we can’t help but think about language. Remember, many of us have been colonized, and have learned to speak the colonizer’s language. Over a thousand years ago, the Arabs colonized the indigenous peoples of North Africa, the Bedawi, and the Amazigh; over 500 years ago, Europeans colonized the Americas. Hence we can say that Arabic, as well as English, Spanish, and French, are colonizing languages, and that they are responsible for the oppression of indigenous languages, which in some cases are nearly extinct, and in others, experiencing a revival, as Catalan is in northeastern Spain. But the colonized also benefit from mastering the colonizer’s language — the conversation goes in both directions.

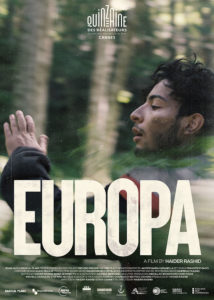

Who belongs and who doesn’t? Nationality is a red-hot issue. The masked men and women of ICE in the US cast their net wide, from Hispanic Americans and undocumented Venezuelan migrants to Irish tourists who overstay their visas, and send them to decrepit detention centers in America’s MAGA-loving south. In Europe, too, nationality is a defining issue. The small boats filled with Kurds, Sudanese, Afghans, and others arrive along the UK coast during a summer of far-right riots in front of asylum seekers’ hotels. Where people come from and their nationalities has become a defining matter of a world in crisis, where people on the move refuse to stop fleeing conflict, civil war, drought, and poverty.

When it comes to securing equal rights for all the people in a land, nationalism is an abject failure, as a poem by Mahmoud Darwish suggests. In “Passport” he writes:

All the hearts of the people are my identity

So take away my passport!

More than half the Palestinians in the world remain stateless, and the Palestinians citizens of Israel do not enjoy the same rights as their Jewish counterparts. Their nationalism means inbuilt discrimination and lower life expectancies.

According to the Merriam Webster dictionary, the five aspects of nationalism include national character, loyalty, and devotion to a nation; national status and membership to a particular nation; political independence or existence as a separate nation; and people with a common origin, tradition, and language and capable of forming or actually constituting a nation-state or an ethnic group, an element in a larger unit. However, the synonyms for nationality widen and enrich the word’s possibilities: ethnicity, race, family, clan, and kindred, to name a few. In the age of social media, nationality no longer strictly refers to a country, it could mean religion, identity, or pure and simple guilt by association, as seen by rightwing conspiracy theorist Laura Loomer’s successful campaign to stop badly wounded and starving Gazan children from receiving medical treatment in the US.

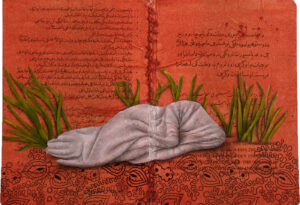

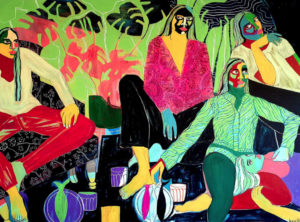

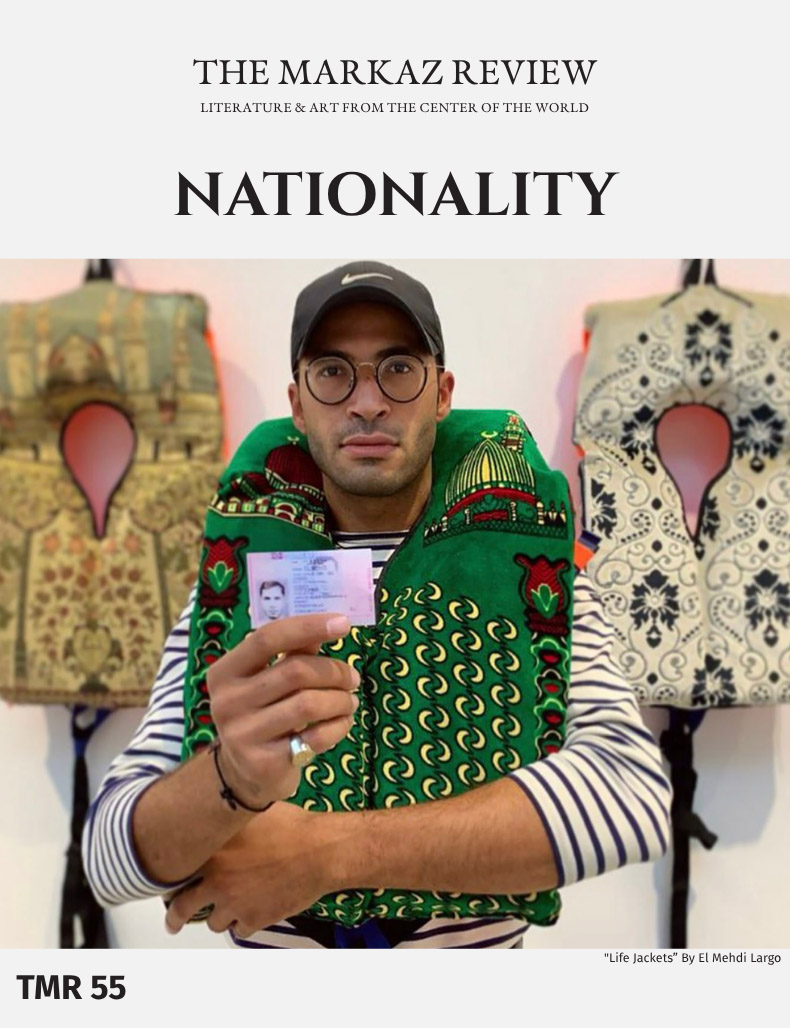

In TMR 55 • NATIONALITY, our centerpiece essay by Adam Makary, “The Grammar of Power,” investigates the hypocrisy and double standards of western liberalism when it comes to the lives of Palestinians. In “We the Wanderers,” our featured artist El Mehdi Largo muses on how he went from being a Moroccan to an Italian, but then in France discovered that he was an Arab after all. Largo insists that “we — immigrants, wanderers — following the setting sun into exile, we are the ultimate seekers of meaning.”

In “The Absent Homeland,” Mayssa Alajjan comes to grips with the fact that although she was born and raised in Lebanon, the country refuses to grant her nationality, because her father was Syrian. In “Home, a State of Restlessness,” a third-generation Muslim Kenyan woman of Indian descent living in London, Neemah Ahamed, longs for life in Athens, as she empathizes with Palestinians in Gaza and diaspora. She writes, “Maybe the paradox is to recognize that home for me is not a place, but a state of ‘restlessness.’” In the short story “Paranoia,” by Parand, contemporary Afghan society is depicted from opposing perspectives — women who are losing all semblance of their freedom, versus the Taliban who have their own rigid ideas about what it means to be Afghan. And in the short story “Sultana to the Rescue,” Lebanese writer MK Harb welcomes a poor woman into his home, unwittingly realizing that it is she who is saving him.

All of our contributors this month, including Amy Omar writing on Turkish wanderer and fiction writer Ayşegül Savaş; Nohshin Bokth exploring the work of British-Iraqi writer Dalia Al-Dujaili; Gaar Adams reviewing two books exploring Gulf identity; and TMR’s 2025-2026 editorial fellow Lara Vergnaud interviewing French-Palestinian and Lebanese novelist Jadd Hilal, work to excavate what it means to be of a people, a culture, a nationality, or even a tribe. At the end of the day, we are richer for the diversity of our identities, and poorer for our divisions.