Melissa Chemam

In the light of recent tragic events in France, in which young Muslims from Chechnia and Tunisia committed mortal knife attacks on a teacher from Conflans-Sainte-Honorine near Paris and three parishioners in a church in Nice, stereotyping discourses about Muslims and Arabic speakers are only adding fuel to the fire.

#Separatisme : le renforcement de l’apprentissage de l’arabe à l’école divisehttps://t.co/qE21a91IgM

— CNEWS (@CNEWS) October 7, 2020

It would seem obvious, however, that if more French people learned and spoke Arabic, intercultural exchanges and dialogue between France and the Arab world would be greatly facilitated, although it’s difficult to say whether this would mean a social sea change that could deter radicalized Islamists.

The subject of Arabic instruction in the schools has been fiercely debated in French media over the past few weeks, with far-right commentators describing Arabic as a threat to France. On television channels like CNews and on the mainstream radio France Inter or again in the daily local newspaper Le Parisien, xenophobic pundits are pushing back against the Arabic language.

Why so much resistance to a language?

Nada Ghosn is a French-born translator from Arabic into French. Her parents came to France from Lebanon in the early 1980s but her father didn’t teach her Arabic. She learned some conversational shami with her mother but mainly gained fluency at university, inspired by a French friend who had no connection to the Arab world. Ghosn later spent a year in Syria to improve her skills. “It’s a very difficult mission to learn Arabic in France,” she avows. “Schools only teach it in certain neighborhoods, the best students are advised to learn other languages. And it’s even more difficult to become an Arabic teacher: there are only three to four positions per year for hundreds of applicants. But also, the language was never made attractive at school; we were told it’s of no use, while there are 200 million speakers in the world. To me, it comes from an old colonial belief that Arabic cultures are beneath Western cultures.”

We cannot produce statistics about ethnic origins in France because a national census based on race or nationality is forbidden and described as discriminatory, so one can only find unscientific information about the country’s population makeup. According to these estimations, there may be more than six million French citizens of Arab heritage, who would thus form the second largest ethnic group in the country, after French people of “French origins” (often mixed with Spanish, Italian and Portuguese heritage).

As the population originating from Arabic-speaking countries is so large, it would only be reasonable for first- and second-generation children to be able to learn their family language properly and, if they learn it at home, to use their skills at school. And for years, some parents, scholars and teachers have been asking for more classes of Arabic in primary and middle schools in France.

Yet, the best places to learn the language in France are in fact at cultural institutions, like the Institut du Monde Arabe and the Institut des Cultures d’Islam, and at some of the best universities, such as INALCO and Sciences Po in Paris, Aix and Strasbourg, and at the University of Montpellier. While France has spent decades creating economic relationships with the Middle East and North Africa, it is deplorable that the country currently has very few experts in the field, and too few Arabic speakers.

Because Arabic is associated with Islam in France, too many think it shouldn’t be promoted let alone taught in schools, as that would only foster terrorism. Yet a 2018 report from the Montaigne Institute entitled The Factory of Islamism urged the Ministry of National Education to relaunch learning of the Arabic language.

According to the report’s author, Hakim El Karoui, an academic at the University of Lyon, “It is essential to mobilize the Ministry of National Education to train managers and teachers in secularism that they do not always know. Teach them to interpret signs of religious extremism too. Understand what is admissible in the name of freedom of belief and what is not because it violates this same freedom of belief…Relaunching the learning of the Arabic language is essential as Arabic courses in mosques have become the best way for Islamists to attract young people to their mosques and schools.”

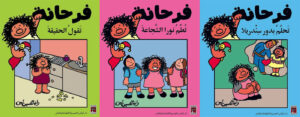

berrakkarakas · Learning arabic

French national Sophie Claudet is an international journalist, trilingual in French, English and Arabic, a rarity in France. She has been based in Palestine, travelled to Iraq and Egypt among many other Arab countries. Yet she learned Arabic because she spent a lot of time in Morocco as a child, mainly listening to people speaking local dialectal Arabic, or Darija. “French high schools do not teach Arabic well,” she says. “Languages in general are not valued in France; they are very poorly taught. The French system does not help you maintain another culture. It only works if you’re a son or daughter of diplomats. But Arabic isn’t taught because of latent racism,” she added.

Sophie went on to learn classical and written Arabic not in France, but in the US, where she moved to study after high school. She reckons that while the US and the UK tend to value workers with a multicultural background, France does not, because of a fear of separatism. “In France, Arabic is automatically associated with Islam, not to a very diverse culture or literature,” she reckons, “and Islam is viewed as a threat to Western values.”

To her point, most politicians in the right-wing parties estimate that a possible strengthening of Arabic in school would fuel separatism of the Franco-Arab population, in a country already considered one of the most Islamophobic in the world.

A number of French education ministers and media personalities, from both right and left parties, have described Arabic as the language of one religion, Islam, as if Latin was only the religion of Christianity and not of a long and eventful historical vehicle for knowledge. They also say that Islam doesn’t belong in France and therefore shouldn’t be promoted.

“But Arabic is simply a beautiful language,” Sophie says, “and a cultural asset in a global world, as well as a language very useful for business. France often thinks it doesn’t need foreign cultures.”

Nada Ghosn shares the same views. “It’s almost impossible to be accepted in France if you have a double culture; it’s considered a betrayal of Republican values. And Arab cultures are more stigmatised than any others. But to me, this is a fascist idea, and goes against values of tolerance and openness. It comes from a superior colonial belief.” She says for instance that her own nieces don’t want to learn Arabic and are often asked at school if they are Muslims, to which they feel safer saying no.

I grew up in a suburb of Paris in the 1990s, at a time when almost no school offered Arabic lessons. Now, in Paris, its suburbs and in big cities like Lyon, Marseille, Montpellier and Aix, more schools have put Arabic on offer, especially since 2003, when then-President Jacques Chirac launched a commission on laïcité and how Arabic and religion were taught in private classes. International high schools like the Lycée Balzac in Paris have taught Arabic for more than two decades. Currently about 400 middle and high schools in Metropolitan France as well as overseas territories offer Arabic as a first, second or third language—10 of them in Paris and 14 in Marseille. There are nearly 15,000 students of Arabic nationwide this year.

Yet only 0.1% of French pupils learn Arabic, while 96.4% are taught English. The most favoured second languages remain Spanish, German, Italian and Russian. The paradox is that Arabic is increasingly becoming an elitist language in some prestigious universities. In fact Arabic is trending, like Mandarin, among French and international students, who most often have no connection with the Arab world.

The United Nations recognizes six official languages which are used in its diplomacy and operations, at UN meetings, and for official documents. These are Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish. The first session of the United Nations General Assembly designated the first five of its official languages in 1946. Arabic was not among them. The Arabic language gained recognition as an official UN language more than 25 years later on December 18, 1973. Then in 2010, the UN Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) established December 18 as Arabic Language Day in order to “celebrate multilingualism and cultural diversity as well as to promote equal use of all six official languages throughout the organization.”

At Sciences Po Paris, about 1,000 students learn Arabic every year, while some 300 devote themselves to the study of Middle Eastern cultures at the university in Menton. “Over the past five years or so, we have seen a steady increase in the number of students who register in Arabic at all levels offered in that language,” according Ruth Grosrichard, Arabic teacher and former head of the Arabic department at Sciences Po. Nowadays, Sciences Po is the French university program with the most students studying Arabic, just behind INALCO, which specializes in Asian and Eastern languages, far ahead of all other higher education institutions.

In a recent interview with France Info, Nada Yafi, director of the Arab Language and Civilization Center at the Institut du Monde Arabe, said that “at university, Arabic is a field of excellence while at primary and secondary school, this language arouses fear.”

So how to explain this discrepancy? According to Nada Yafi, it is a specifically French problem as “in other European countries, the language is not the subject of debate and does not generate tension.” Two years prior, she had penned in the review Orient XXI that “behind the debate of ideas, we see hidden passions resurface, old wounds: that of an unassimilated war in Algeria; that of national pride inconsolable at the loss of a vast empire.”

The French Minister of National Education, Jean-Michel Blanquer, and the Interior Minister, Gérald Darmarin, recently announced that they want to see more children learn Arabic in schools, instead of mosques for instance. They haven’t detailed a concrete plan yet to train more Arabic teachers. But specialists in Arabic language and cultures insist that Arabic should not be seen as a counter-actor against extreme religious beliefs. The language existed prior to Islam, wrote Francoise Lorcerie, researcher at the French scientific center CNRS, and it is used beyond the purpose of spirituality.

In the meantime, let’s hope that other educators manage to keep on teaching tolerance, along with an interest in foreign cultures and languages.