Rebecca Ruth Gould interviews award-winning Palestinian writer Nasser Abu Srour, finally free after 32 years in Israeli prisons.

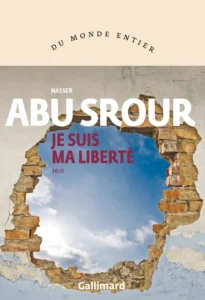

In October 2025, after thirty-two years of incarceration in Israeli prisons, Palestinian prisoner Nasser Abu Srour was released as part of the Hamas-Israeli ceasefire agreement. Along with 154 other freed prisoners, he was immediately placed on a bus to Egypt. A year earlier, Abu Srour’s 2022 book, The Tale of a Wall: Reflections on the Meaning of Hope and Freedom (Other Press), had been published to wide acclaim in English, and translated into French as Je Suis Ma Liberté by Stéphanie Dujols (Gallimard). Like all his writing, this book was composed entirely from prison, where Abu Srour was serving a life sentence. Accused of being an accomplice to the murder of an Israeli intelligence officer, he was convicted following a confession extracted through torture. He wrote in the knowledge that he might never be released. Je Suis Ma Liberté was awarded the 2025 Prix de la littérature arabe by the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris.

Two months following his release, in December 2025, I had the honor of spending a long evening over Zoom with Nasser Abu Srour, who is based in Cairo while awaiting a decision about his future. Joining us was his niece Shatha Abu Srour, a disability rights activist based in Palestine. Our conversation took place in English and Arabic, with Shatha translating for Nasser, who occasionally interjected English into his answers.

This conversation is not a verbatim transcript of our multilingual conversation; certain sections have been edited for clarity and to make up for technical faults. Nasser reported that our interview was the first conversation he had ever had over Zoom, since the technology had not been invented at the time he entered prison. Even iPhones were new inventions for him, and he was still adjusting to owning one. He spoke of sensory overload and of the extreme disorientation he had been experiencing following his release from prison.

REBECCA RUTH GOULD for TMR: Let’s talk about your book The Tale of a Wall, the process of writing it, and why you wrote it. This book belongs to a tradition of prison writing and will be read for many decades to come. Let’s give some context for how you came to write this work. Did you grow up with a sense of yourself as a writer? How and when did you discover yourself as a writer?

NASSER ABU SROUR: I was 13 years old when I first wrote something of substance, a poem about women. At the time, I thought it was a naive and juvenile work. Then I found it again some years later. The poem was complex, not naïve. Also, it showed that I was angry with women. I don’t recall the circumstances precisely, but it seems that I had said something nice to a girl who refused or rejected me, which is why I was angry. I can’t remember exactly what happened. My attitude, luckily, had changed towards women. This passion to write was born in me from that time, when I was 13 or 14 years old.

TMR: I wanted to also speak about your mother Hajjeh Mazyouneh Abu Srour, how she shaped your writing and your view of the world. Among supporters of Palestine, she’s quite famous. There are many videos of her speaking about you and calling for your release. You write about her in your book and were still in prison when she passed away. Can you introduce her as a person?

NAS: My mother used to live in a village right near the refugee camp where I was born, where she later got married. She married when she was probably 14 years old, and she didn’t even know how to fry an egg. She learned to cook from my father while she was living with him in the camp. She was still a child when she first gave birth. A child who gave birth to a child. Just like all of us, she was subject to Israel’s policies and practices against Palestinian refugees. She was the most beautiful feminine presence in my life.

Then suddenly, my father became unable to take care of the household, of our financial needs. My mother took over the responsibilities of the house. She went to work and started taking care of all the details: school, pocket money, food, clothes, furniture. She carried everything related to the house, financially and otherwise. In this way, we transitioned from patriarchy to matriarchy. In letting go of so many of his responsibilities, my father also let go of his voice in making decisions for our family.

My mother raised us and took an entrepreneurial role in the family. She gave us space and freedom. She didn’t interfere in my life, my decisions, my behaviors, or my actions. Unlike my peers and their mothers, she provided me with a space of freedom.

When the First Intifada (1987-1993) started, she allowed me to participate in it. There were fathers and mothers who would not allow their children to participate. My mother was concerned and scared for me, but she didn’t forbid me. Then she turned into a mother who would go from one prison to another looking for me. She made every visit to the prison she could. Unless she was abroad, or she wasn’t allowed to visit because the Israelis once claimed that she presented a security threat. I saw her every two weeks. Once, she came to visit in a wheelchair.

I used to ask my mother not to die, to wait for me. She vowed to keep this promise. I told her to hold on to life. And she did all that she could. She put my father’s sword right by her bed, believing that she was using it to fight what we call the angel of death. And she succeeded in manipulating death, even though she suffered several strokes, one that almost took her sight. Then, all of a sudden, her body couldn’t continue this pattern. Couldn’t keep waiting.

This happened during the war. Only 70 days before my release, she decided to die. I tried to understand why she did that. Maybe she didn’t want to be an ordinary mother or an ordinary woman. She used to go to protests, participate in conferences, talk about her battle, about me. Maybe she liked this role. Maybe she wanted to be a legend who doesn’t live by normal rules. I had no choice but to accept this decision, forgive her, and remain alone without this feminine presence in my life. Just like in epics, my mother wanted to die as a tragic hero. Such heroes don’t die a normal death. They choose to die differently.

TMR: How many siblings do you have?

NAS: Yes, yes, I have two other brothers and five sisters.

TMR: And you are the eldest?

NAS: No, I’m in the middle.

TMR: In school, were there any teachers or other people in your life, who shaped the person you became?

NAS: Most of the teachers were refugees. Some were from villages, some the cities, but the majority were refugees. I talked about my experience with teachers in my second book On the Bed of Writing. They were exposed to all forms of violence. Some were beaten while coming to school. Others had lost their loved ones or had their houses attacked. They would come to our school in a rage and would pour their rage out on us. Their brutal beatings traumatized us. The relationship between students and teachers was built on fear. One of the teachers was from Jerusalem, and from the first time he saw us, he decided to call us cows. Why did he see us as animals, we wondered. Not all teachers were like that. Another teacher would bring banned poems for us to read. He would hide them and read them to us. He wanted us to learn about our land. I was shaped by both the positives and negatives of my school experience.

TMR: Now let’s talk about your time in prison. I was fascinated by how you discuss the passage of time in The Tale of a Wall. Can you compare the experience of time before you were imprisoned with the experience of time while you were in prison, and with now? What’s it like from a day-to-day perspective?

NAS: Time is connected to movement. In the camp, there is no movement. There’s just stillness, as if life doesn’t move. In the camp where we were raised, we grew up, but it didn’t feel like there was movement. Time is frozen, and isolated from the geographies surrounding it. In the camp we hear the same stories from our fathers and from our grandfathers: the Nakba, forced displacement, killing, ethnic cleansing, genocide. It was as if time stopped in 1948. I had a theory about my time and my experience with time in prison. I used to experience time as if it was accumulative. I could feel and touch it. And it had weight, and it was heavy. The more years pass, the heavier they become. I feel like I’m carrying the years on my back. Maybe this is why I started experiencing backache.

My relationship with time isn’t like Shakespeare’s. He says that time is eternal for those in love. It is fast for those who are happy, slow for those who are in pain. I did not have the luxury to experience time like Shakespeare did. In the camp, time was frozen, and in prison, it accumulated like a mess.

TMR: How do you experience time now? Is it a continuation of the prison time, or do you experience it differently?

NAS: I’m helpless to explain or clarify my relationship with time. I used to be isolated, and I used to like isolation. And I’ve been raised in isolation, so I experienced chaos when I was released. I’m still experiencing this helplessness because now I’m unable to explain or interpret my relationship with time. And this is annoying my loved ones and my siblings. I am drowning in all the gifts they brought. I’m not used to those things. I didn’t have them, especially during the last two years in prison.

On the first day of my release, I was given an iPhone, an iPhone 17 Pro Max. There are so many details in the room itself, so many details in this room. I’ve never been in a hotel. I don’t know what time means when I’m on the phone. I need to know my relationship also with everything around me. When I leave this room, I have to go back to it, sometimes making five trips to the room, because I always forget something. Now I’m living outside Palestine, in Egypt. I’m living in a geography with which I’m unable to define my relationship. If I were in China, I would feel the same as I feel now in Egypt. I feel like I’m exhausted by geography, because I’m out of Palestine. My relationship with geography is vague and undefined. And this has probably confused my relationship with time. Place and time are connected.

TMR: Can you talk about your second book, On the Bed of Writing, which is only available in Arabic? I don’t think many readers will know about it. Could you introduce it? Are there plans for it to be translated into English?

NAS: I finished On the Bed of Writing while I was in prison, before the genocide. I didn’t want to publish it while the war was still ongoing, out of respect for what the readers were dealing with. It seemed like a bad time to exhaust people with this book while they were trying to survive. This book talks about writing as a kind of therapy. And this is how it was. In addition to me trying to explain what writing is to me, I also went back to stations in my life that I needed to revisit. I needed to be frank about those stations or stages in my life, to embrace them.

In this book, I was direct. I was naked and clear. Some may protest my nakedness. But I don’t care. I write as I believe. I must write exactly as I am. I’m part of this universe. But the universe does not agree. There is a universal identity that we want to talk to, that we want to be part of. We want to also contribute, to be able to shape and reshape and belong to, to affect and be affected by, but this wish is not reciprocated. Maybe people in the West will find something that speaks to their thoughts and their feelings. And they will find something interesting in it, and something that may speak to their own problems. We also are affected by the West, by its vocabulary and its reflections on us.

For almost five hundred years, since the Ottoman occupation, we have been isolated. And this has also affected our development. Our culture and our heritage have been stolen and put in western museums and in western universities, in Paris, in London, in the U.S. I don’t want to be separated from this, from this universe. I want to be part of it, and this is why I want for my writings to be translated.

TMR: When your Arabic publisher Dar al-Adab published The Tale of a Wall, they classified it as a novel (roman). However, in English and other languages this book has been presented to readers as a memoir. How do you see the book in terms of genre?

NAS: When Dar al-Adab classified Tale of a Wall as a novel, I was angry. I don’t write novels. I don’t even read them. I used to, but about 10 years ago I stopped. In our age, in our world, we need writers who write from a sense of commitment, not fantasy literature. Dar al-Adab classified this book as a novel because they had no other classification they could use.

Writers in my view are obliged to reflect the reality around them, the reality in which they live. We must write directly. In ancient Arabic literature, writers like Ibn al-Muqaffa used allegory in works like Kalila and Dimna. He has animals speak truths that humans could not say. Such writers did not write directly because they were afraid of their rulers. Writers today must reject this art of indirection. We don’t need symbolism or allegory. We need writing that conveys reality.

We have enough problems — enough suffering, enough poverty — that we don’t need writers to invent additional sufferings as a means of distracting the audience. This is particularly true in the Middle East. Perhaps writers in the West have that luxury, but not here. Here, writers must attend to what is actually happening in their world. Only this will create the conditions for change. They also must be willing to pay the price for telling the truth about what they see.

TMR: So you’re more in agreement with the English publisher’s presentation of your book, The Tale of a Wall, as a memoir. Were you able to work at all with the translator Luke Leafgren when it was being rendered into English?

NAS: With The Tale of a Wall, I didn’t have a chance to be part of the translation process. Luke made a good effort. I’m satisfied with it. I believe I would have been able to help with the translation if I could have. Sometimes one word in Arabic needs four words in English to explain it. Some words lose their soul, their spirit, when they are translated. This is a problem of translation in general. If the second book will be translated, and there’s a chance it will be, I will make an effort to be involved and to help with the process.

TMR: Your work has been translated into English and French. Are there any other languages into which it has been translated?

NAS: Italian, Chinese, Romanian, Spanish, and Greek.

TMR: Let’s turn to your life now, after having been released. Are you able to write, or are you taking a break? Do you see yourself writing another book soon?

NAS: Before the war started, I had begun a new book. I wrote almost half of it, and I do want to continue the other half. But I’m still suffering the same problem with time. I can’t find time to find time. I’m unable to identify my relationship with time and my relationship with geography is still confused, which makes writing difficult. I’m also afraid that I lost my language. I want to find the moment when I’m stable enough to write. I want to write about the moment of my liberation and my trip to Egypt. I’m trying to establish my relationship with the geography. I’m making an effort to regain the ability to write. I’m trying to talk to the problems or the chaos I’m experiencing with myself. And in the future, I may need therapists or psychiatric help. If so, I’ll ask for it. I’m optimistic. I’m making some small attempts here and there. I might start with short passages, short things.

TMR: In other interviews, you mentioned that you’ve received invitations to relocate to other countries, so you might not stay in Egypt. Will you decide to go somewhere else?

NAS: The available options are very few: Qatar, Turkey, and Malaysia. Spain was on the list and it was cancelled. Until now, I haven’t decided where I’ll go. This isn’t only up to me, it’s a decision that also belongs to my family and my fiancée. My future wife also has the right to decide where her life will be. I can’t be selfish. And so this thorny issue still hasn’t been settled. But I want a place that is hurt and that hurts. I am made of exhaustion, and I need an exhausted place to be able to write. I can’t write in a place that isn’t exhausted. I want a place that is like me. I am a hurt person, an exhausted person. This is who I was and who I am still. I want a place where I can shape, or I can feel like we both can shape this solidarity between us, me and place.

The reason we have difficulty finding a place is that each regime and each people see us as a security issue, as a thorn in the throat, or in the ass. Europe didn’t open its doors to us. And the Arab region also has many problems, and doesn’t want to deal with us.

TMR: By “us,” do you mean the prisoners who were exchanged, who were recently released?

NAS: Yes.

TMR: Is there any hope for Palestinian freedom in the near future? Is there anything that you’d like the world to understand better about this struggle? Or is there anything that gives you hope about the Palestinian struggle?

NAS: Where there is a will, there is a hope. As Mahmoud Darwish once said, Palestinians can’t stop hoping. We can’t give up. To stop hoping means to stop altogether. We want to keep moving. And in this movement, there is hope. So we need to get unstuck. Hope exists in each and every Palestinian, and each and every Palestinian is responsible for seeding and planting this hope. This is our work now.

What I want to say is that the Nakba is ongoing. It started in 1948 and we’re still living it today. Before they were using donkeys to transfer Palestinians after uprooting them from their villages and cities. Now they are using airplanes, as when they transferred Salah al-Hamouri from Palestine to France. The only difference between 1947 and 2025 are in the means and colors. The colors of the Nakba when it began were in black and white. Yet, the ongoing Nakba is in all the colors. This is an invitation to the world; it is an issue that must be solved. It is an international responsibility carried by the whole world. International law entails that people who are oppressed or occupied have the right to fight, including through violent resistance.

Although we didn’t write this law, we believed it. We believe this discourse and we did what we did because we believed. Then why, when we act within the framework of this law, are we considered terrorists? Why are you silent while the Palestinian people are being killed? Do we have different blood? We have the same blood. We feel pain, we feel scared, we feel hungry when we are starved. Why doesn’t the world want to see? Why do they ignore the massacres? Almost 70,000 people have been killed in two years. The United Nations said that no city in the world has been exposed to all the bombs that have been dropped on Gaza.

We are exhausted. We feel like we are alone. We want to be part of this world and want to be liberated. Yet, we continue. The Palestinian people are still resisting, and they will not leave, and will not stop. We will do everything we can to liberate our people. If anyone thinks we will stop before liberation is achieved, they are mistaken. They are delusional. We will not stop.

TMR: As you said, it’s been happening for almost a century. Well, I have now four hours of recordings to turn into an interview. Thank you so much. Also, I should have said congratulations at the beginning. None of us knew that you would ever be free. When I read your book, I never could have guessed that I would soon be speaking with you in freedom, and you didn’t know either. This is a victory, regardless of all the terror that’s happening, and that an important achievement.