Today in Egypt, for the sake of enabling 24/7 surveillance, the newest prisons make it impossible to ever turn off the lights.

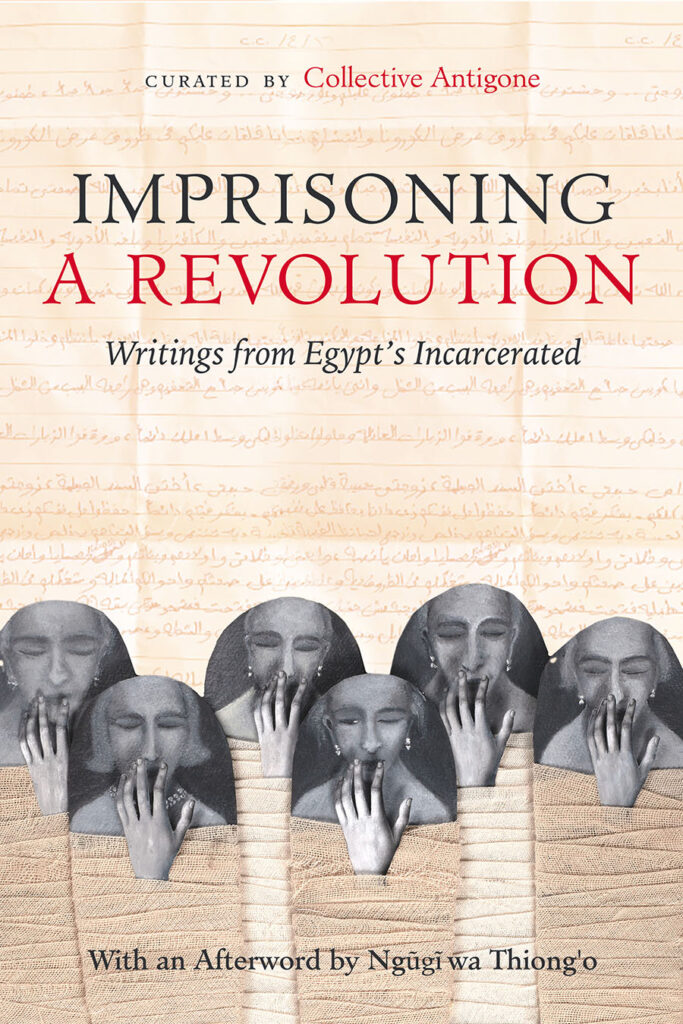

Imprisoning a Revolution: Writings from Egypt’s Incarcerated, editors Collective Antigone

University of California Press 2025

ISBN 9780520401372

Amid the hundreds of political prisoners whose stories of incarceration fill this book is an unnamed man, who is given the nickname “Marcel Proust” by Ahmed Naji, the novelist and fellow inmate who tells his story. This “Marcel Proust” of Egypt’s prisons is not a writer by profession. He became a writer by accident, when he found himself locked up, charged in pre-trial detention with a crime — corruption — that he did not commit.

As “Marcel Proust” awaits the outcome of his case, he begins writing his memoirs. He writes for his future self, in order not to forget “even one day of the injustice he had lived through while in prison.” During the four years of his imprisonment, he fills his notebooks with pedestrian content: when he awakes, what he eats, whom he speaks with. Just as they did for the original Proust, these minute details of daily life have sacred value for this Egyptian prisoner. Transcribing them becomes a means of retrieving lost time, of rescuing his suffering and forced confinement from oblivion.

After four years of waiting, “Marcel Proust” is finally acquitted. However, the prospect of freedom is bittersweet: everything he has written during the four years of his confinement must be destroyed. Writing in prison is forbidden, and the guards will not let him take his notebooks with him, to the world outside. He is given a choice: burn everything you wrote while in prison and go free or keep what you wrote and remain incarcerated. Even though he was declared innocent, he had broken the law by writing in prison, an act that would be used to legitimate further incarceration. “Marcel Proust” knows that, whenever he is released, he will have to destroy his prison writings anyway, so he succumbs to the inevitable. He watches his meticulous account of his prison years devoured by flames, tears streaming from his eyes. It is a high price to pay for freedom.

Writing as the Highest Form of Resistance

The story of the Egyptian “Marcel Proust” appears in the foreword to Imprisoning a Revolution (2025), a collection of prison writings from post-revolutionary Egypt. The foreword was penned by Naji, himself a former prisoner and writer who was incarcerated for 300 days following the publication of his novel, Using Life (2014). Upon his arrest, Naji became the first writer to be imprisoned in modern Egyptian history specifically for his literary work. He was charged with “violating public modesty,” due to the novel’s sexual and drug references. Given Naji’s status as a harbinger of oppressions to come, he is the perfect person to introduce this collection of writing from Egypt’s prisons from 2011 to 2023, curated by Collective Antigone.

Naji shares with the other contributors a vision of prison writing as “the highest form of resistance.” He speaks for all authors in this volume when he describes the act of writing from prison as “a declaration that their will has not been broken, and that they are capable of thinking, creating and innovating.” The relationship between writing and resistance reverberates throughout each of the book’s contributions. At the most basic level, writing creates a bond between the world inside the prison cell and the world outside. It keeps the prisoner’s incarcerated self alive.

The texts that constitute Imprisoning a Revolution originate in the suppressions that followed Egypt’s Arab Spring. Taken together, these writings expose a burgeoning literature that is also a carceral network. Comprising texts by 46 different authors — six of them anonymous — the collection includes letters, poems, essays, and even scriptural commentaries, as well as drawings and sketches created in prison. Each text was written from within Egypt’s vast carceral network, and many of their authors are still currently behind bars. These “artifacts of prison contraband” were smuggled out at significant risk to their authors, who were driven by “an irrepressible desire to tell one’s story, regardless of the cost.”

The editors decline to refer to themselves as such, preferring to be called curators instead. Their preference for curation over editorship as the organizing principle for this work makes sense, given that many of the texts were culled from external sources, in particular El-Nadeem, Center Against Violence and Torture, as well as from social media and private correspondence. With respect to its contents, the book is more like a selection of found art than an edited collection. And while the texts were not written with the intention of being published alongside one other, they work remarkably well together to shine a light on the Egyptian experience of incarceration. Themes and ideas recur. Different prisoners explain how they’ve been forced to come to terms with the way time flows in prison, how light shines differently behind bars, and how the self is transformed through prolonged confinement.

Imprisoning a Revolution presents a range of carceral experiences across the political and religious spectrum. The distinction between “political” and “criminal” prisoners is deeply entrenched in the existing discourse on prison literature, yet the book most fully comes to life precisely when the authors reject these binaries. For example, in his contribution, journalist Ahmed Gamal Zaida criticizes the “bogeyman myth” that attends the notion of a “criminal prisoner.” As Zaida points out, among the so-called “criminal prisoners” are “many innocents, and many who were imprisoned for trivialities like ‘stealing electricity current.’” The Egyptian “Marcel Proust” is one such case: an “average employee” who was not targeted as a dissident, but who became one as his freedom was stolen by an unjust system. He chose to peacefully resist prison’s constraints by writing. In a state that distributes justice unequally (as most states do), no distinction between criminal and political prisoner can ever be airtight. Any prison literature worth the name will take on board this volume’s deliberate blurring of these boundaries.

All the prisoner-authors included in this book were incarcerated for their resistance, in some way or form, to the Egyptian security state. The reasons, however, vary greatly. Some are secular activists. Others are members of the Muslim Brotherhood. Some were implicated in and accused of crimes that they did not commit, while others committed actions that they knew would result in their imprisonment. Well-known journalists, such as Alaa Abd El-Fattah and his sister Sanaa Seif, Yara Sallam, Sarah Hegazi (who tragically committed suicide soon after her release), and Maheinour el-Massry are included alongside scores of anonymous prisoners. Poets Ahmed Douma and Mohsen Mohamed appear alongside the short-lived Egyptian president Mohammed Morsi, who was imprisoned immediately following Sisi’s military coup and died from torture in a courtroom in 2019. The testimony included in this collection is Morsi’s final message to the people of Egypt, which was smuggled out of prison two weeks before he died and published on his Facebook page after his death. The fact that even a head of state died from the torture he received in prison attests to the ubiquity of Egypt’s carceral politics, and to the fact that no one is safe.

The structure of the collection makes visible the scars of recent history: the counterrevolution that followed the uprising of 2011, the repressions and massacres of protestors, and the neoliberal state of exception that has been in place in Egypt since 1968, with only a brief interlude between 1980 and 1981. The detailed introduction examines Egypt’s much longer history of using incarceration as an instrument of state repression; it is particularly valuable in exposing the continuities between colonial practices of imprisonment and contemporary modes of incarceration.

Few collections of prison literature so effectively document a specific moment in time, and thereby clarify why Egypt’s prison system has expanded so dramatically in recent decades. Neoliberalism has presided over the rise of increasingly invasive surveillance techniques, imposed on prisoners’ bodies in the name of efficiency. While the average size of prison cells has increased, the conditions under which prisoners are incarcerated have isolated them even further from the world outside. For the sake of enabling 24/7 surveillance, the newest prisons make it impossible to ever turn off the lights.

Writing in Prison to Survive

The conception of prison writing as resistance is also the core concern of the interview that concludes the book, with Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who reflects at length on his own experience of imprisonment in 1977. Just as the authors in this collection were targeted for their writing, Ngũgĩ was imprisoned after writing a play in his native Gikuyu language, I Will Marry When I Want (Ngaahika Ndeenda), that criticized the ruling elite and exposed the corruption of the Kenyan state. Written in Gikuyu at a time when vernacular African languages were heavily restricted in favor of English by postcolonial states such as Kenya, the play was performed for a wide audience by non-professional actors, including factory workers, farmers, and students. The popular performance of this play by a mobilized grassroots collective, combined with the vernacular language in which it was composed, was seen as a threat to the state, which decided to imprison the author and ban the play. Ngũgĩ recalls how he discovered himself as a writer while in prison. “Even if you’re not a writer at first,” he explains, “you start to write in prison in order to survive.”

In a story that resonates with contemporary Egyptian tales of imprisonment, Ngũgĩ tells of how he tricked the prison guards into allowing him to write the novel that became Devil on the Cross (1980) at a time when all forms of creative writing were forbidden to him. The guards tried to pressure him into writing a confession that repented of his “crime” of having written the play. Rather than admitting regret for using his native language to defy colonial strictures or for exposing the state’s corruption, Ngũgĩ instead used the pretense of writing a confession to extract paper from his guards. On this paper he began drafting the text that became the basis for his novel. When that strategy no longer worked, Ngugi continued to write the novel on toilet paper.

Once he was released, Ngũgĩ published the novel that he’d written in prison. In the decades since its publication, Devil on the Cross has become a landmark work of Gikuyu literature and a testimony to Ngũgĩ’s spirit of resistance from within his prison cell. Recalling this experience three decades later, the writer explains that his incarceration led him to discover “the power of my mother tongue” as a means of political mobilization and of aesthetic expression. Writing in prison was, in Ngũgĩ’s words, “a daily, almost hourly, assertion of my will to remain human and free despite the state’s program of animal degradation of political prisoners.”

The Egyptian political prisoners whose letters, poems, and essays are included in this collection wanted their words to be “read, circulated, and acted upon.” They were also constituting an archive and writing a vital new chapter for Middle Eastern prison literature, an archive that includes novels such as Wisam Rafeedie’s The Trinity of Fundamentals and Nasser Abu Srour’s The Tale of a Wall. As the curators remind us: “Each generation of prisoners has, in a way, bequeathed its writing as a warning, or invitation, to push future generations to continue the struggle no matter how slim the chance of victory.” Prison writing is oriented to the future in ways that other forms of writing are not: the vision of a better world that led the authors to sacrifice their freedom can only be achieved through generations of struggle.

Such is the fear that prison writing instils in the authorities that they turn it into contraband, even when its content is not overtly political. Words are dangerous, because they are vehicles of truth.

Anonymity and Erasure

Alongside its ideological diversity and historical awareness, this collection is unique because many of those involved in producing this work have chosen to remain anonymous. Hence, Collective Antigone. The collective was named for the Greek heroine Antigone, best known from Sophocles’ plays, who defied the king’s authority in order to bury her brother’s body. The curators point out in an interview that Antigone “has long served as inspiration for those seeking justice within authoritarian systems.”

While the power of Antigone’s struggle for justice is impossible to deny, it is distinct in significant ways from the struggle of political prisoners around the world today. Contemporary political prisoners have sacrificed their freedom in service to a revolutionary ideal. They aim to change the norms by which we live. By contrast, Antigone did not especially identify with the insurgency of her brother Polynices, who waged war on his brother Eteocles, the ruler of Thebes.

Antigone was determined to bury Polynices honorably, but this was because he was her brother rather than because she believed his cause was a righteous one. Antigone’s rebellion and her defiance of the king’s authority is fundamentally an act of fidelity to her brother. Egypt’s political prisoners, by contrast, participate in a collective struggle that looks beyond the horizons of the biological family, even as they draw courage from Antigone’s story.

One arguable downside of the methodology of anonymity is that it is sometimes extended to the translator. Many translators in the collection are named, but it also happens that the translated status of the text goes unmentioned. Perhaps we are expected to assume that every text is originally in Arabic. But some texts are written in an Arabic that foresees its eventual worldwide circulation, while other texts are internal monologues for which the writer does not expect an international reception. Some prison literature is written for the self, to resist the banality of prison life, as with the Egyptian “Marcel Proust.” Other prison literature is conceived from a desire to share a truth, and the intention is for it to be widely read even before it is written. These differences emerge most clearly in detailed examinations of the process of translation.

Sidestepping translation can have the effect of flattening differences in audience and intention, and of encouraging the reader to assume that all texts were equally destined for an English afterlife. When the Arabic originals are not discussed, it becomes more difficult to track the process through which the text’s intention was formed. My point here is not to suggest that there was a viable alternative to anonymity; the exigency of the political situation makes that the only responsible choice. Anonymity is a means of survival in this context; it is the necessary condition around which the rest of the text must be organized. Nonetheless, the text itself is always visible, and it should have been possible to account in more detail for how an interior reflection in Arabic becomes an English text.

Anonymity, however, also helps to shift attention away from the curators of this collection and onto the prisoners themselves. It also reminds us of the precarious circumstances faced by those who speak out from their prison cells and even within the Egyptian diaspora. In their conversation with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the curators explain how the Egyptian security services operate today: “[p]eople disappear for months, and no one knows where they are until the family gets a phone call from the police station, the office of a prosecutor, or even the morgue.”

Acts of forced disappearance have been a feature of Egypt’s carceral system for decades, but they accelerated in scale and brutality during the Gaza genocide. In July 2025, during a pro-Palestine protest which involved the storming of Ma’asara police station in southern Cairo’s Helwan district, 27-year-old Mohsen Mustafa and his 23-year-old cousin Ahmed Sherif Ahmed Abdul Wahab were forcibly disappeared. Nothing has been heard of them since.

The cases of Mustafa and Wahab remind us that, for every imprisoned writer whose words are included in this book, there are thousands of prisoners who never got the chance to share their voices with the world, or who had to destroy what they had written in prison before they could be released. Many of the testimonies in this collection attest to a peculiar circumstance of prison life: even when it is possible to clandestinely document prison experience, the price of freedom is the erasure of the circumstances of incarceration. Since prison literature is above all concerned with memorialization, the precarity of its material existence threatens to undermine the entire project of prison writing.

Shaping the World to Come

Such is the fear that prison writing instils in the authorities that they turn it into contraband, even when its content is not overtly political. Words are dangerous, because they are vehicles of truth. Prisoners’ words expose the state’s hypocrisy and its reliance on terror to extract obedience and compliance. They document torture, corruption, and double standards. They hold public officials to account, and impose a limit on their power.

States imprison dissidents in order to silence them. Yet sometimes incarceration has the opposite effect: it galvanizes a movement, mobilizes a people, and clarifies a political goal. Even when the protest is suppressed and the cause unrecognized, when the prisoner falls silent or dies while in prison, the tradition of prison literature ensures that their deaths are not in vain. The very intensity of the state’s efforts to silence and suppress those who write from prison demonstrates the necessity of resistance. Consider what the fascist Italy’s state prosecutor Michele Isgrò said at the trial of Italian Marxist philosopher and lifelong political prisoner Antonio Gramsci in 1928 as part of his campaign to silence him. “We must stop this brain from functioning for twenty years,” Isgrò declared to the court.

The prosecutor achieved his aim in the short term. Gramsci died in 1937, a few days after his release from prison. Over the longer term, however, it is not to Isgrò’s death sentence but to Gramsci’s vision that we turn when we seek out ways to forge a better world. A plaque erected in 1945 at the entrance to the prison in the town of Turin where Gramsci was incarcerated during the final decade of his life attests to the impact of his jottings from his cell on the world outside. The inscription reads: “Teacher, liberator, martyr, who announced to the foolish executioners their ruin, to a dying nation salvation, and to the working class victory.” The words on the plaque are a touchstone for the Collective Antigone’s project of curating Egyptian prison literature for the revolutionary vision imprisoned by the security state and for the sake of generations to come. The Egyptian prisoners whose words comprise this collection are Gramsci’s rightful heirs.

Gramsci may have been unable to alter his immediate circumstances from his prison cell, but he achieved something much more monumental: he changed our world and altered the shape of the world to come. So too with the incarcerated contributors to Imprisoning a Revolution. Some may die in prison, never having known the full impact of their words. Those who wrote anonymously may never have their individual achievements recognized. They teach us that the cause for which they struggle exceeds the importance of individual recognition.

In Egypt and across the Middle East, the act of writing from within prison and of smuggling prison literature outside is invariably a collective effort. This collective may be made up of members with radically different aims, but they share a willingness to sacrifice their personal happiness and satisfaction for the sake of a cause. By recording and contesting the conditions of their incarceration — and by resisting the state that put them behind bars due to their revolutionary activism — these writers participate in a tradition of prison writing that is at least a millennium old, and which has particular importance for Middle Eastern literatures from Iran to Syria to Palestine. The writers who create this tradition draw strength from the past while making possible a different future.