For Palestinian artist Rana Samara, TMR's featured artist this month, intimacy is not just about love and sex, but is rather a mixture of connection, comfort and feeling at home, as her latest exhibition at Zawyeh Gallery in Dubai in 2022, Inner Sanctuary, aptly demonstrated.

As humans, we often look for intimacy in another being whom we elect as special. However, great art reminds us that a sense of intimacy is not found necessarily in one single person, but is all around us. It’s a way of looking at reality, of places and objects that are seemingly mundane but can actually comfort us and bring us solace and a sense of home.

This kind of intimacy is precisely the subject of exploration of Palestinian artist Rana Samara. For the artist, intimacy is not just about love and sex, but is rather a mixture of connection, comfort, and feeling at home. It can be found in the presence of another person, as well as in something simple as savoring food from one’s home country when abroad.

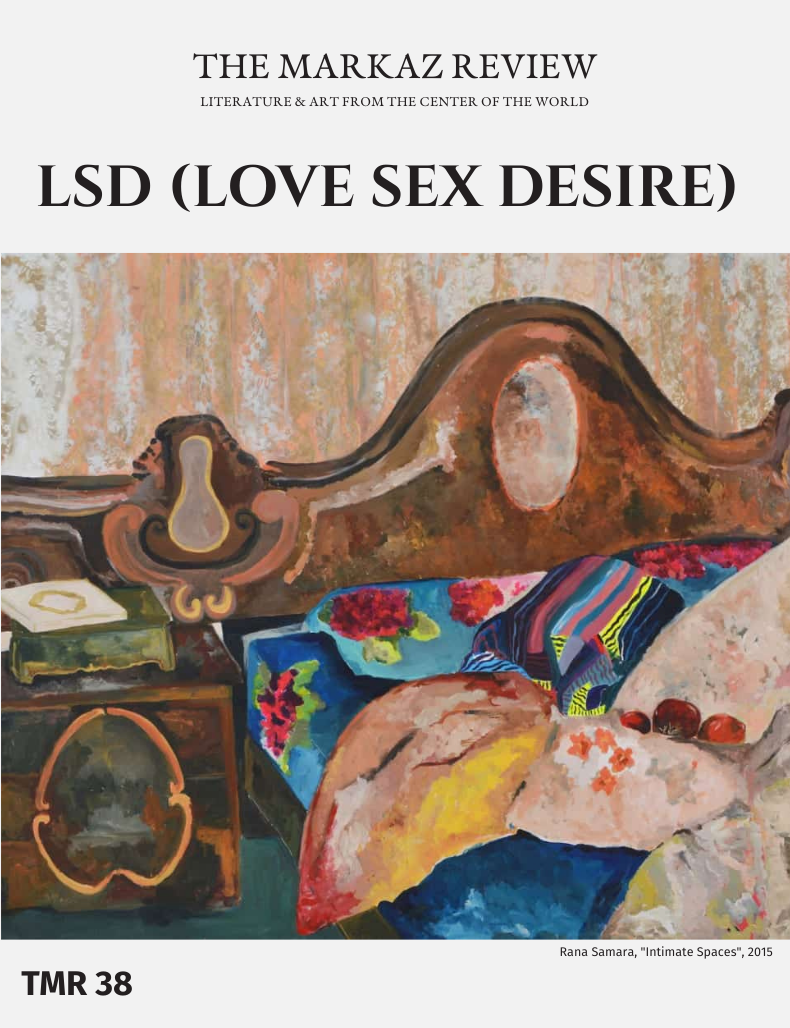

Her latest exhibition at Zawyeh Gallery in Dubai in 2022 was aptly called Inner Sanctuary. The show depicted her personal spaces, unveiling a layer of profound emotions associated with each location. From her favorite cafe to her studio, kitchen, bedroom, cafes, and even an abandoned swimming pool, Samara romanticized and sentimentally explored the settings that define her daily life.

In her painting, the artist employs bright colors and decorative motifs to convey contentment, calmness, anxiety, or frustration. Samara’s depictions range from warm and loving places of the heart to disquieting non-places, like hospital rooms, with one constant: the absence of human beings.

Inner Sanctuary emphasizes the records of human imprints found in various corners, portraying elements like a suit, a slipper, plates of food, and plants, highlighting the remnants people leave behind.

In a previous series, Samara investigated a feeling of intimacy in regard to the Palestinian experience, something that is often overlooked. She did ground research, spent months at a time at Al-Amari Refugee Camp, and had conversations with women about sensitive topics such as virginity, intimacy, sexual desire, and gender norms, revealing these women’s convictions about relationships and roles. This resulted in her 2016 show Intimate Space at Zawyeh Gallery.

Though Rana is a determined, strong-willed woman with clear views, in her conversations she showed up as a listener who holds no judgment, but simply a willingness to understand. These conversations form the cornerstone of Rana’s paintings, videos, installations, and embroidery.

“At Al-Amari Refugee Camp I began wondering about the private lives of couples living in such condensed spaces that afford them almost no privacy,” says the artist. “This privacy is especially difficult to achieve considering the large size of most Palestinian families and the cramped proximity in which neighbors and families live.”

In the fashion of many women artists, Rana Samara tackles the political through the personal, showing that the two dimensions are inevitably intermingled. In the series Intimate Spaces she depicts rooms with unmade beds, with clear signs of recent lovemaking. The colors are bright, and the sensations they convey are warmth and comfort.

The feeling they evoke is similar to the famous installation “My Bed” by Tracey Emin, which consists of her messy bed. Like the British artist, Rana Samara is seen as a bit of a rebel, but the challenges she had to face are quite different. A mother of three children and hailing from a conservative background, Rana pursued a bachelor’s degree at the International Art Academy, Ramallah, and a two-year MA in Fine Art at Northwestern University in Chicago.

“Since I was a child I have always been interested in colors and I was fascinated with everything that moved around me,” recounts Rana. “I always was drawing and always knew I wanted to be an artist but, had to figure out precisely what shape that would take. So my first degree was in graphic design and then I continued to study fine arts, but couldn’t find myself in either of the two. With contemporary art, I finally discovered my own environment.”

.

Naima Morelli: As a woman artist, do you think that you face difficulties in entering the art world?

Rana Samara: I believe that if women want something they will do it. There are no artists in my family, and my dad wanted me to study finance, but after one semester I dropped out of school to study art. I kept studying for eight years, which is a long time. Being a mom – I have three kids – it was hard. I was fighting with my family, with my ex-husband. They kept on questioning what I was doing, pointing out that I couldn’t make a living out of art and I was a woman. In Palestine in particular, the only way to make a living with art is to be a teacher. When Zawyeh Gallery came to me, I had just graduated from school. The gallerist came to my exhibition and was fascinated by my paintings. To my great surprise, he even bought them, which was really shocking for me at the time.

TMR: Why do you think you caught the gallery’s attention?

RS: Look, there are a lot of artists in Palestine. Many give up even though they are great. Here the established artists – who we love – are those who are prevalent in the gallery spaces. So any young artist who wants to emerge really needs to bring something new and special to the conversation, in terms of materials but especially in terms of topics. All the artists are talking about the political struggle in Palestine – and I’m doing that too, but through a different lens.

TMR: Another work that really fascinated me was your “Virginity Handkerchiefs” installation. Can you tell me a bit about how the idea for that work came about?

RS: This idea for the work came one day during the preparation for a wedding, hearing my mother and my aunt talking about these white handkerchiefs they bought. According to a Palestinian tradition, a bloodstained handkerchief is given to the mother of the groom, which proves that the bride was a virgin. My immediate reaction was: “What the fuck guys! What are you doing?” My mother told me to stay silent because I’d mess everything up. At that moment I felt an urge to make work about this. It took me six months to elaborate on how to represent this concept. I didn’t want to take sides necessarily. In my art, I want to step out and let other people talk about this topic. So I bought 200 pieces of this handkerchief and gave it to people and asked them to write on it what they thought about virginity. I got the handkerchiefs back and I basically curated them.

TMR: You often involve other people, creating collaborative projects. Sometimes this means having conversations with women and interrogating them on themes that are not openly spoken about in Palestinian society or are even seen as taboo. I was wondering about your approach to letting women open up.

RS: It’s a skill. And it improves with time. I lived in the refugee camp for seven months and I met women, we talked about food, cooking, kids, and only then I could ask my questions. That’s how you build trust. However, I have always been good at making people talk about personal subjects, I have been told I’m a good listener.

TMR: You pointed out you don’t want to convey your views in the work, but it seems that you still feel strongly about many of these subjects. How do you manage your own emotions while making art?

RS: I have mixed feelings about these topics, and I’m sure I will never forget these conversations. There are a lot of stories that broke my heart. Sometimes I’m happy because women can start talking and opening up about this part of their lives. I have always dreamed of creating social change in a way that inspires people. For many women I met it’s hard to improve their situation, but being a woman with kids myself, I think I inspire them in a way.

TMR: Why do you feel this need to separate yourself from the work?

RS: I think if I want to talk about myself it’s a different topic. It’s not the same concept. And of course, when I get to take pictures of the room of a woman I have spoken with, or if she sends me the pictures, I always look for some personal connection with it. For example, I had a friend who sent me a picture of his hotel room where he had sex. When I saw it was a hotel I cringed because it felt really cold. Really really cold. And observing my reaction, made me reflect on my artistic process. The room itself was interesting, but I felt something was missing. I couldn’t paint it.

TMR: Your latest exhibition was Inner Sanctuary. Do you feel this series was an evolution compared to the work you exhibited in Intimate Spaces?

RS: For this show, I continued the theme of intimate spaces as containers of stories. The name of the exhibition is related to the possibility of each element of reality becoming an inner sanctuary. It means that you can find a place that is meaningful to you, a comfort zone of sorts. For example, the coffee shop I drove to is my inner sanctuary, or even a hospital room can be someone’s inner sanctuary. From this idea came the name of the exhibition.

TMR: Why aren’t there any people in your paintings?

RS: For me, it’s not interesting to have paintings including people. It would be something that would direct my imagination in too much of a specific way. If I see a space, endless possibilities are happening, but when there are people, I feel I’m putting constraints on the viewers. There is only one painting that has one human, and it’s my daughter, but that’s part of a specific project.

TMR: Do you feel that objects and places convey the emotions of the people who inhabit them, or pass by?

RS: I definitely feel that objects contain feelings, and even store trauma sometimes. Mostly my paintings are based on stories of places. I take pictures of these places and then paint them according to my sensations about the space. Right now, I’m working on a new project based on landscapes, which will result in my next solo show some time next year. It would be, of course, an intimate look at landscapes.

TMR: What is intimacy for you?

RS: I’ll try to explain it with a story. The first month I was in Chicago I was going to a Middle Eastern restaurant to eat. In the beginning the city, the people, everything felt really cold. Only when I was eating at that restaurant I felt soothed. It was because of the music, the food, the table, the owner, and of course the food. I was eating by myself and I found myself thinking: this is really intimate. I realized intimacy is not only about sex. The act of eating is intimate. This might sound weird, but I was asking all the people who were eating alone if I could join them and eat together. Most of the time they said yes and we would start a conversation from there. This is why I say intimacy is not just about physical space, or about sex. It’s about something else I can’t even name. I guess this is why I’m making art about it.