On July 5, 2022, Algeria celebrated the 60th anniversary of its independence from France. When it comes to Algeria, author and Nobel Prize laureate Albert Camus remains a problematic figure who today is both claimed and rejected by Algerian intellectuals and artists.

Oliver Gloag

Camus was always ambivalent about colonialism in Algeria and this ambivalence greatly affected him. In 1943, he wrote in his diary: “Algeria. I do not know if I make myself understood well. But I have the same feeling when returning to Algeria that one does looking at the face of a child. And despite this, I know that all is not pure.”

For Camus, Algerian nationalism could not be allowed to express itself formally at the expense of France; Algerian independence was out of the question.

In the late 1930s Camus had advocated the passage of the Blum-Viollette bill, which would have granted French citizenship to a very small minority of Arab men (a few thousand). All efforts to pass the bill had failed in the 1930s, but the Second World War changed everything. During the German occupation, French resistance leaders, desperate for Arab support, accepted a proposal — The Manifesto of the Algerian People — from Arab nationalist leaders — including Messali Hadj representing the Algerian People’s Party (PPA), Sheikh Bachir al-Ibrahimi for the Muslim religious scholars, and Ferhat Abbas for those in favor of autonomy. The goal of the Manifesto was the establishment of an autonomous Algerian state.

Although in March 1943 the governor of French Algeria accepted the Manifesto as a basis for forthcoming negotiations, he later withdrew his support. The original granting of the Manifesto had raised the hopes of Algerian nationalists. This withdrawal, combined with the desperation of the Algerian people, gravely suffering from wartime food restrictions, created an explosive situation.

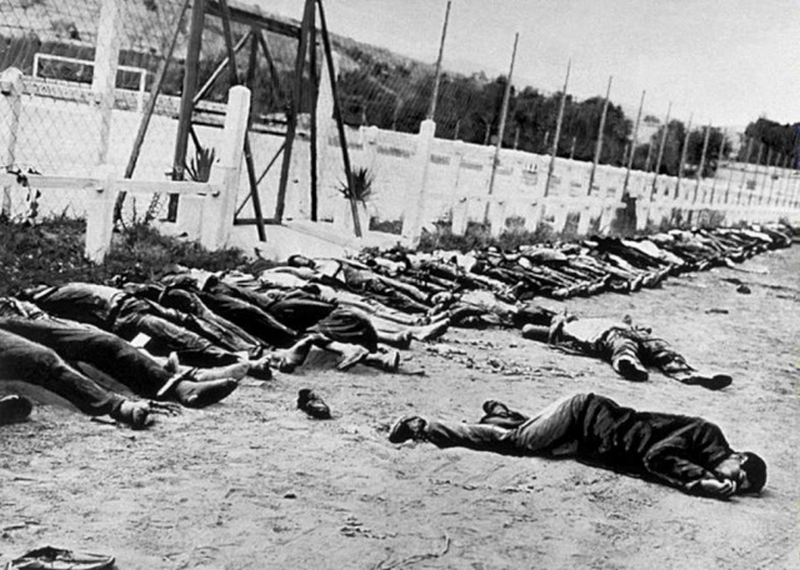

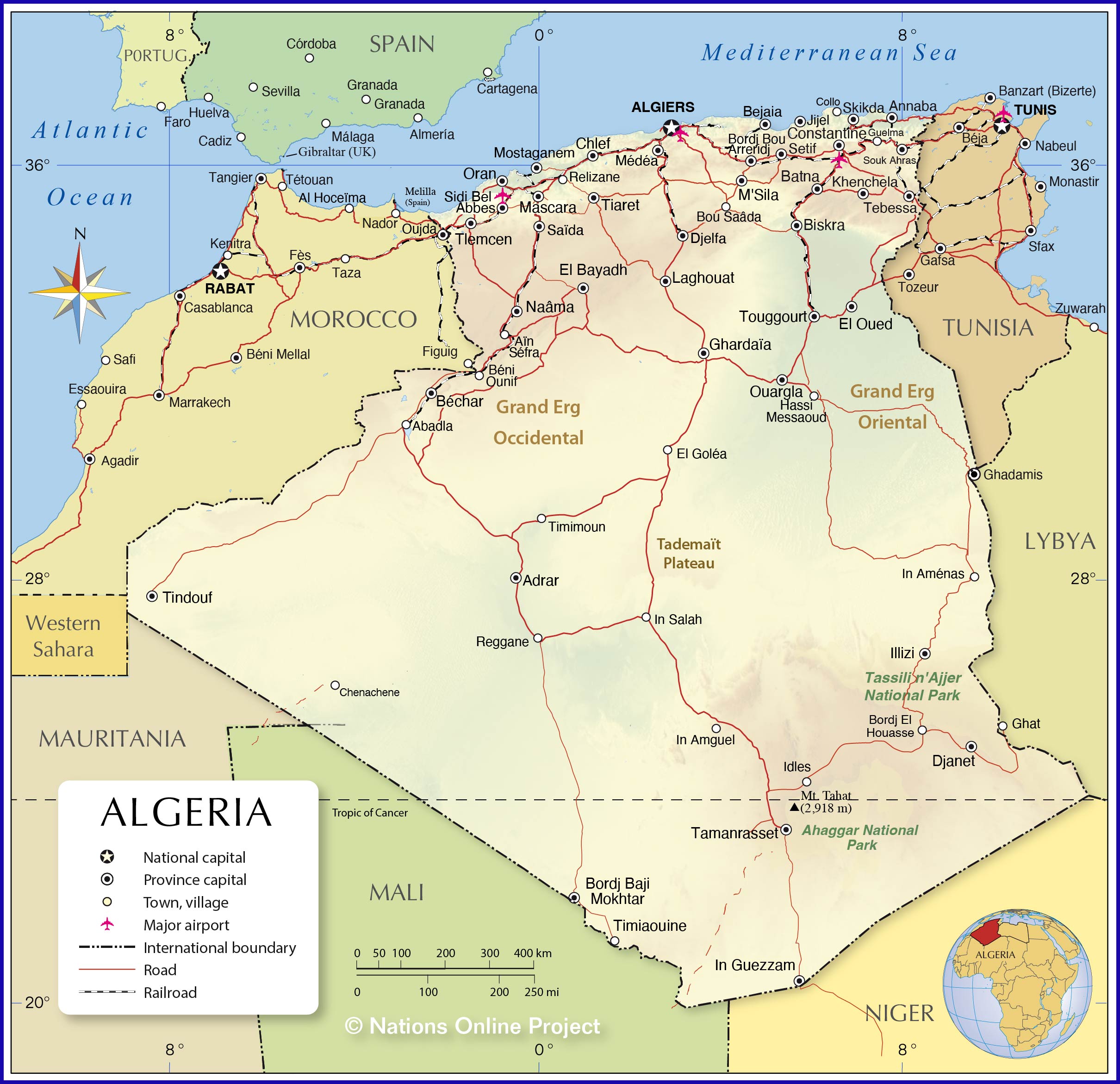

In early 1944, Charles de Gaulle, now head of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, the interim government of France, offered to pass the Blum-Viollette bill into law. However, sensing weakness, the Algerian nationalist leaders refused. The French authorities continued to blow hot and cold: on 7 March 1944, de Gaulle unilaterally revoked the indigenous code (though there were still no equal voting rights), but on 25 April 1945, he had Messali Hadj, the most charismatic, radical, and courageous Algerian nationalist leader, deported to Brazzaville in the Congo. This was the context for the riots of VE Day that ended with the massacres in Sétif and Guelma.

An Algerian population which had suffered the wartime restrictions more than the metropolitan French, a nationalist leadership which had believed that independence was at hand, a people who had contributed thousands of its young men to the first French victories on the Italian front — were now unable to wave their own flag in celebration of VE Day. The French and pieds-noirs’ reaction was a veritable massacre which lasted for weeks; thousands of Algerians were slaughtered. It set back for ten years the movement for Algerian independence, but it also ensured that upon its re-emergence the actors would be more determined than ever. The context for the month-long repression was a weakened French state, desperate to hold on to a colonial empire by any means.

Though he never discussed in detail the massacres of Sétif and Guelma, Camus was enthusiastic about the abolition of the indigenous code and the de facto passing of the Blum-Viollette bill, although the bloody massacres showed that it was too little, too late. Camus pushed for more rights to be granted to Algerians after the war. He wanted more Algerians to have access to education and all graduates from primary school to obtain French citizenship, yet he stopped short of asking for voting rights for all. Camus was to be the advocate of peace and compromise, with one objective in mind: for Algeria to remain French. He appealed mainly to the metropolitan authorities, writing in the press that the effort to retain Algeria as a part of France demanded a “second conquest”; in other words, Algerian hearts and minds had to be won over.

However, the situation demanded greater concessions, a fact of which Camus was acutely aware. In the aftermath of the Second World War, it was no longer possible to ignore the demands of colonized people for their rights; these demands surfaced at every level: political, cultural, and on the streets. During this period, the long-repressed colonial reality began slowly to emerge in Camus’s fiction, until it eventually took center stage.

The Exile and the Kingdom

The last of Camus’ s fiction published in his lifetime, The Exile and the Kingdom is a collection of short stories, many of which are steeped in the North African context. Some of these stories echo Camus’s anger at Sartre and the aftermath of their quarrel. But in others his growing concern with the rise of nationalism in Algeria is omnipresent, though never discussed directly until “The Host.”

The first short story, “The Adulterous Woman,” is the story of Janine, the wife of a pied-noir cloth salesman. They travel into the desert — 200 miles south of Algiers — so that he can sell his wares to the local population. Camus tells the story from her point of view — her impressions as they go deeper into what increasingly seems a foreign land. At first, Janine describes Arabs as an indistinct group. She feels they are feigning sleep; she does not like their silence and indifference. Throughout the story, she feels estranged by Arabs and comments on their language, which she heard all her life but does not understand. She hates the “stupid arrogance” of an Arab who is looking at her, to which her husband adds, “they think they can do anything now.” These remarks highlight that the abolition of the indigenous code in 1944 is a source of the pieds-noirs’ fear. There is also fear of coming unrest. The entire time, the wife feels that all the Arabs are surrounding her, as though they are an oppressive force.

In the final scene, Janine wakes up in the middle of the night, goes onto the balcony, stares at the horizon, and is enthralled by the forces of nature — a quintessential Camusian moment of bonheur, a “perfect” moment when “time stops.” Simultaneously, the sounds from the Arab town stop. (In Camus’s words: “A knot that habit, boredom, years had tied, was coming undone, slowly.”) Symbolically, the Arabs are gone. In an intense communion with nature, Janine transcends the cold, the weight of others, the anguish of living and dying. Finally, upon returning and facing her husband in their small hotel room she is overcome with tears. She has experienced a cathartic moment.

For Camus, these symbolic moments of merging with nature represent a powerful rejection of human history. It is the fantasy of an atemporal Algeria void of most of its indigenous inhabitants, an inchoate fantasy which is the sole source of true, intense bliss — or bonheur — for the character, and indeed for Camus himself.

“The Host” is arguably the most powerful story in the collection. The hero is Daru, a pied-noir teacher. He lives in the mountains of Algeria in a home which doubles as the school. Daru is greeted one cold winter morning with the arrival on a donkey of Balducci, a tough local policeman with a heart of gold — Camus’s version of the salt of the earth pied-noir who appears frequently in his fiction. With Balducci, on foot and tied to the donkey with a rope, is a local Arab man accused of killing a relative. (As in The Stranger, the Arab is never named.) Daru is summarily charged with bringing the man to the authorities, something he is loath to do. But Balducci makes it a matter of loyalty and honor to try and force Daru’s hand, to put him on the spot. Camus felt the same way during the Algerian War of Independence, stuck between two warring parties with no way to express his own perspective. Thus, the hero Daru can be seen as a stand-in for Camus.

Though Daru accepts Balducci’s account of the Arab man’s guilt at face value, he does not want to deliver him to the authorities. Neither does he want to upset the old man. To put pressure on Daru, Balducci says that war is brewing, Arabs may rise up, and then “we will all be involved.” Daru does not want to be involved, but historical events catch up with him. Daru and Balducci argue and finally, reluctantly, Daru agrees to sign a note confirming that he has received the prisoner, but he does not promise to deliver him. This creates a rift between the two men. Once Balducci leaves, Daru feels guilty that he let Balducci down. Daru, like Camus, is caught between the desire to avoid conflict and his allegiance and closeness to the pied-noir community.

Furious at the Arab for committing a murder and upset at Balducci for ordering him to deliver the prisoner to the authorities, Daru is caught between two conflicting allegiances. So, in the end Daru compromises. He brings the Arab halfway toward the city and the prison and tells him that east is prison and south are nomads who would take him as one of their own. After hesitating, the Arab goes east, and Daru returns home.

Camus portrays Daru as a man caught between two factions, but a kind man who tries to be fair. We are meant to feel empathy for him, which deliberately does not prepare us for the shock of the final paragraph. Upon returning to his classroom, Daru finds written on the blackboard the followings words of menace: “you have delivered our brother. You will pay.” Kind, fair, but misunderstood by all, alone, pressured by his own, threatened by Arabs — this is how Camus saw himself in the midst of the struggle for Algerian independence.

Commentators are split on the interpretation of the end of the story: the focus is on either Daru as a genuinely noble figure (after all, he refuses to send the Arab man to prison), or on how odd it is for a narrative set in colonial times to have a settler portrayed as a victim and sole sympathetic character.

A civil truce

The war in Algeria, which began on All Saints’ Day in 1954, was affecting Camus not only as a writer, a French citizen, and a pied-noir, but also as a public figure. Two years after the start of the war, Camus travelled to Algiers to give a talk, an impassioned plea for peace. This is known as his “Call for a Civil Truce in Algeria.”

He was under no illusion about stopping the war; his goal was an agreement between the two warring parties to end the killing of innocents. The atmosphere surrounding Camus’s intervention was one of hostility from unexpected quarters: the pied-noir mayor of Algiers had refused to host the conference, and when a venue was found — thanks to moderate Algerian organizations, who also organized security — he could hear hostile cries from the street of the pieds-noirs crowd: “death to Camus! Death to Mendès-France (premier of France, 1954–5, who had been in favor of ending colonial wars)! Long live French Algeria!” Ultimately, the conference was shortened for fear of violence from the pieds-noirs groups.

Camus opened his speech by immediately condemning the protesters who wished to silence him. It was a moving retelling of his motivation and his plight: “for 20 years I have done what I could to help concord between our two people.” It was also an admission of failure: you can heckle me, you can even laugh at me, Camus implied, but at this stage the emergency is to prevent undue suffering.

He attempted to separate the Algerians’ fight for justice from their fight for independence, which he described as “foreign ambitions” which would definitively ruin France. Was this a reference to the Soviet Union? In the Cold War context, the specter of the Soviet Union taking over was a classic argument which supporters of colonial powers made for continued control over a colony. At the heart of the speech was this: for Camus, Algerian nationalism could not be allowed to express itself formally at the expense of France; Algerian independence was out of the question. Keep at it, and there will be perpetual war, Camus said to his largely Algerian audience. His message of peace also included an indirect warning: if you don’t negotiate, the fighting will continue ad infinitum.

Camus concluded by praising the members of the Muslim community for organizing the conference and told the mixed audience that what moved them was humanism, not politics. Camus here displayed an almost endearing naivety; in fact, the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) was the force behind the conference. Amar Ouzegane, a friend of Camus and a fellow member of the Communist Party in the 1930s, was one of the organizers of the conference. He was also, unbeknownst to Camus, a member of the FLN. The objective was to claim Camus, to convince him that the revolution was justified.

Many years later Ouzegane would explain, “the civil truce was a way for us [the FLN] to help honest folks, enemies of injustice but hostile to violence, to open their eyes and to progressively realize that the FLN was right.” Did the FLN have a chance to convince Camus? This was very unlikely, but certainly that Camus gave his speech for peace surrounded by hundreds of pieds-noirs baying for his death was a step in the right direction as far as the FLN was concerned; for them, it was a public relations coup.

This moment is emblematic of Camus’s ambiguous position arising from the combination of his sincere desire for peace and his inability to perceive the scope of the injustice suffered by Algerians throughout the French occupation. Camus oscillates between nationalism and humanism, desperately attempting the impossible combination of the two.

In a letter to a close friend after the conference, Camus writes, “I returned from Algeria quite depressed. What is happening is strengthening my conviction. It is all for me a ‘malheur personnel.’” As malheur in French is the opposite of bonheur, for Camus this was a tragedy, and a personal disaster.

Throughout his life, Camus repressed his modest pied-noir origins in various ways: by the style of his dress starting as a teenager, by the style and subject matter of his first three major works (universal themes), even by his focus on Spain, the country which outwardly most concerned him from a political perspective (rather than Algeria), and which served as an idealized space where he could combine his Spanish roots with a progressive cause. But, in the late 1950s, with the very existence of French Algeria at stake, Camus had no choice but to address his roots and takes sides in the ongoing conflict, as he would in his posthumous novel, The First Man. It is perhaps for that reason the best introduction to his work, for it makes clear what is at the root of his refusal of history and what motivates his veneration of nature.

What emerges in his fiction but was until then always implicit or hidden is an unvarnished emotional defence of French settlers, of French Algeria — it is a coming out, a mask that falls: nothing is more important to Camus than France’s presence in Algeria. This is the story of the hidden genesis behind his works, his commitments, his worldview, even his love of nature. His last book, The First Man, is the sincere cry of a man who feels he has nothing to lose, nothing to hide anymore. It is the key to all his works.

This unfinished novel takes place mostly during the war. There is a clear sense that Algerians are going to reclaim their country, and pervasive feelings of anxiety, fear, and anger on the part of the settlers at the center of the story. Camus tries to justify the French presence in Algeria: he is facing the colonial situation from an unprecedented position, from a place of weakness. The war is Camus’s worst fear come true. The novel itself is highly autobiographical; it is the story of a pied-noir named Jacques Cormery, who now lives in France. (In the manuscript he occasionally is named Albert and Cormery was Camus’s paternal grandmother’s last name.) A first-person narrative from Jacques alternates with dialogues between settlers and Jacques’s childhood memories. When Jacques, who lives in Paris, returns to his native land, he is confronted with the settlers’ anger, fear, and resentment towards the rise of Arab nationalism. The novel features lengthy dialogues between an aggrieved settler and a less intransigently anti-Arab one alongside a narrator who attempts to make us understand the settlers’ anger.

One such dialogue occurs when Levesque, a friend of Jacques’s father, reminisces about their 1905 service in the French army fighting Moroccans. Upon finding the mutilated body of a French soldier — which is described at length — Jacques’s father says about Moroccan combatants:

“A man stops himself. That’s what a man does, if not…” And then he calmed down. …And suddenly he shouted: “Filthy race, what a race, all of them, all…”

This passage is in keeping with many others in the novel, where most of the dialogue denies the humanity of Arabs. The actions of Arabs against the French invaders are described in detail, while the crimes of Europeans are only suggested. The end of this passage is also emblematic, for it concludes with a definitive judgement about race emanating from the father figure, who is idealized throughout the novel. His racist cry is presented to the reader as the “understandable” reaction of a victim. Camus also includes attempts to explain what the narrator calls the xenophobia of the settlers:

Unemployment … was the most feared ill [by the pieds-noirs]. This explained that the workers, who in daily life were always the most tolerant of men, were always xenophobes when it came to work, accusing in succession Italians, Spaniards, Jews, Arabs and finally the whole world of stealing their work — a disconcerting attitude certainly for intellectuals who theorize on the working class, but yet quite human and very excusable.

Camus does not challenge the racism of pieds-noirs in French Algeria but instead justifies it. He uses class concerns (unemployment) as an explanation for the xenophobic reaction of the settlers. Through the narrator, racism occurs here as part of human nature, as an understandable reaction from ultimately likeable characters. Here Camus also uses his modest origins like a weapon, at times inferring that these origins give him an awareness and an authenticity lacking in some of his other interlocutors with more privileged backgrounds. This is yet another allusion to Sartre.

Perhaps oddly, the main adversary in this defence of French Algeria is not the Arab rebel, but the French anti-colonial left. In another telling passage, a settler who owns a vineyard is uprooting the vines in his property to ensure that Arabs will not be able to profit from them once they take back their land. When asked what he is doing by Cormery, the settler responds with what is meant to be bitter irony: “young man, since what we have done is a crime, we should erase it.”

Camus depicts the landowner as a tragic figure: an admirable hard-working man, an old pied-noir, one of those who “are being insulted in Paris.” Yet this destruction of the vineyards harks back to one of the most somber hours of the French conquest of Algeria: in 1840 when Alexis de Tocqueville’s friends, General de La Moricière and future governor-general of Algeria Bugeaud, agreed to make the systematic destruction of Arab crops a policy to “prevent the Arabs from enjoying the fruits of their fields.” This uprooting of olive trees and the destruction or confiscation of fields were a crucial moment in France’s conquest of Algeria. Forced to leave that conquered territory, the French once again destroy cultivated land, but this time Camus describes them as being victims of an injustice.

This final unfinished novel, The First Man, becomes a platform for the expression of the white settlers’ resentment. In particular, resentment against the metropole (the central Parisian authority but also mainland France in general) is present throughout, for example, in this exchange between the main character — Camus’s alter ego, Cormery — and a pied-noir farmer who tells him: “I have sent my family to Algiers [for safety] and I will die here. They don’t understand that in Paris.” The farmer’s hatred of the metropole is such that he expresses more respect for the Arabs who violently oppose his rule. The farm owner advises his Arab workers to join the Algerian resistance because “there are no men in France”—that is, the pieds-noirs will lose because of the weakness of the metropolitan French. This is the despair of the white settler; he feels abandoned by Paris and as a consequence, resigned to the rise of the Algerian resistance.

Another leitmotif in this work is the idealization of a time period that pre-dates human existence. For Camus sees himself, through Cormery, as torn between two universes, Europe and Algeria, separated by the Mediterranean:

The Mediterranean delineated two universes with me, one where in measured spaces memories and names were preserved, and the other where the wind and the sand erased the traces of men over great spaces.

That is, Algeria is the place with no memories, no traces of men. Here Camus equates once more the notion of anonymity with Algeria (and therefore with Algerians) but also on a moral scale equates it with a place where human history is insignificant — which allows the negation not only of the past of indigenous people, but also of the recent past of colonialism.

The book’s title is also an appeal to a past of a different kind. The biblical connotations are evident, and it is interesting that Camus thought about naming the first character Adam. This is part of a pieds-noirs or colonialist fantasy that is unexpressed but present: the notion that no man was present on this land before him — much like Adam and Eve,. This is a world vision that places European settlers and European myth respectively at the center of all things. For example, Camus describes the main character as being born “on a land with no ancestors and no memory … where old age found none of the succor from melancholy which it receives in civilized countries …”

In quintessential Camusian fashion, Cormery conceives of himself as being part of nature in a long stream of consciousness which was to be the end of the manuscript:

Like a solitary wave, always moving whose destiny is to break once and forever, a pure passion to live facing total death, [he] felt for life, youth, beings escape him without being able to do anything for them and abandoned only to this blind hope that this obscure force which for so many years had lifted him above days, nourished him immeasurably, equal to the direst of circumstances, would furnish him as well, and from the same tireless generosity from which she had given him his reasons to live, some reasons to age and die with revolt.

This “obscure force” is Camus’s thought — with all its strengths and limitations; the force is at once a refusal of intelligence and a regression towards nature: he is part of a greater whole, a wave in the sea. This unity with nature had previously helped Camus to transcend and escape the colonial realities. This is no longer possible; we are left with Camus’s moving plea that this force come to the rescue, even in defeat. His realization is that the dream of a return to “the good old days” is illusory; his colonial fantasy of the French as “indigenous to Algeria” is dismantled. Camus’s dismay is overwhelming.

The dream of a world ruled by nature rather than by society was shattered as well in his very first published novel. Returning to The Stranger we can see that the Arab was killed not only because he occupied the privileged space of Meursault’s communion with the sea and the sun, but because he announced the inevitability of the rise of the Arab “other.” The First Man reflects both an inchoate desire to negate this new reality (the coming of Algerian independence) and a long mourning of the old colonial order.

Throughout this final work, Camus was torn between his reformist, socially conscious leanings and his contradictory desire for Algeria to remain forever tethered to France. The text accordingly tries to legitimize France’s colonization of Algeria in the most interesting of ways. Instead of attempting to speak to France’s civilizing mission (a classic argument employed by France for centuries), or the need for colonization to maintain France’s status as a great power (a more naked Realpolitik perspective which Camus employed at times), Camus describes the pied-noir settlers as revolutionaries. This new argument, which he developed in The First Man, was going to be the final attempt to resolve this contradiction for him.

Camus writes that the early settlers of Algeria had been a part of the French revolution of 1848, specifically he states they had been victims of the anti-revolutionary repression that took place in June of that year and left for Algeria as a result. However, historians challenge the notion that there was a revolutionary French working class in Algeria. According to the leading authority on the matter, historian Charles-André Julien (1891–1991), the French workers who left France for Algeria in the aftermath of the repression of June 1848 became oppressors themselves: “the workers and artisans who had survived the days of June 48 … were those who were the most ruthless against Arabs.”

Camus tried here to claim the revolutionary struggles of 1848 to legitimize the presence of French settlers in Algeria. This view is unusual for Camus, who typically rejects human history as a frame of reference. However, for the cause of the pieds-noirs, Camus was ready to undo everything, even his own beliefs and ahistorical principles.

The First Man is an ode and a defence to the pieds-noirs. It is a tragic work where Camus for the first time faces his contradiction and resolutely chooses the side of French Algeria, as he wrote in his diary in May 1958:

My job is to write my books and to fight when the freedom of mine and my people is threatened. Nothing else.

The emblematic expression of Camus’s choice of his roots over justice was also his cri du cœur during a press conference in Stockholm, on the occasion of his winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. When attacked by a militant of the FLN for espousing the cause of Eastern Europeans but not Algerians, he retorted: “I believe in Justice, but I will defend my mother before Justice.” It was an odd response, because it implicitly recognized that the French colonial system was unjust. Put another way, Camus’s response was a defence of his mother but also the admission that the cause of the FLN was just. Camus was broken on a personal level by the events in Algeria, as he wrote in his diary: “… Algeria obsesses me. Too late, too late … My land lost, I will be worth nothing.”

Camus could not conceive of Algerian independence, nor could he conceive of himself as separate from French Algeria. It was his “red line in the sand,” the boundary which should not be crossed, the ultimate taboo. Algeria was the jewel in France’s colonial empire, so important that the French authorities considered it a region of France. It was not just a military conquest; it was an administrative one as well. Camus was defined and defined himself by colonial Algeria and could not live without it. Yet the paradox is that for many observers and readers, what remains is the sense that Camus persuasively uses the rhetoric of humanism while supporting French sovereignty over Algeria. This contradiction tore Camus apart while he was alive, but the illusion that he had resolved it remains.

Yet on some level Camus did resolve it. In 1956, with Algerian independence now a very real possibility, he put forth a more ambitious proposal for compromise. He wanted to give Algerians quasi-complete autonomy with a bicameral system. There would be two parliaments, one for Algerians, one for French settlers, and power would be shared equally except for two domains — the military and economic, which would remain the purview of the French. The result would have delegated day-to-day administration to the Algerians.

Although Camus underestimated the balance of power between the French and Algerian sides, what he proposed for Algeria was a compromise similar in many ways to the current situation of many former French African colonies, which, though sovereign, share a currency controlled by Paris, and that they should be the locus for substantial French economic interests as well as French military bases. This parallel between Camus’s proposition for Algeria and what has emerged in most French-speaking African countries today explains in part why he has become the intellectual legitimization for today’s neo-colonial reality, and why so many present-day Western political and cultural figures claim him as one of their own.

Muy buen artículo: veraz, informado, aclaratorio. Todo lo que ahora vamos a necesitar para pensar sobre África.

A very interesting text. It looks like his Eurocentric part of him pretended to be disguised into a universalism.