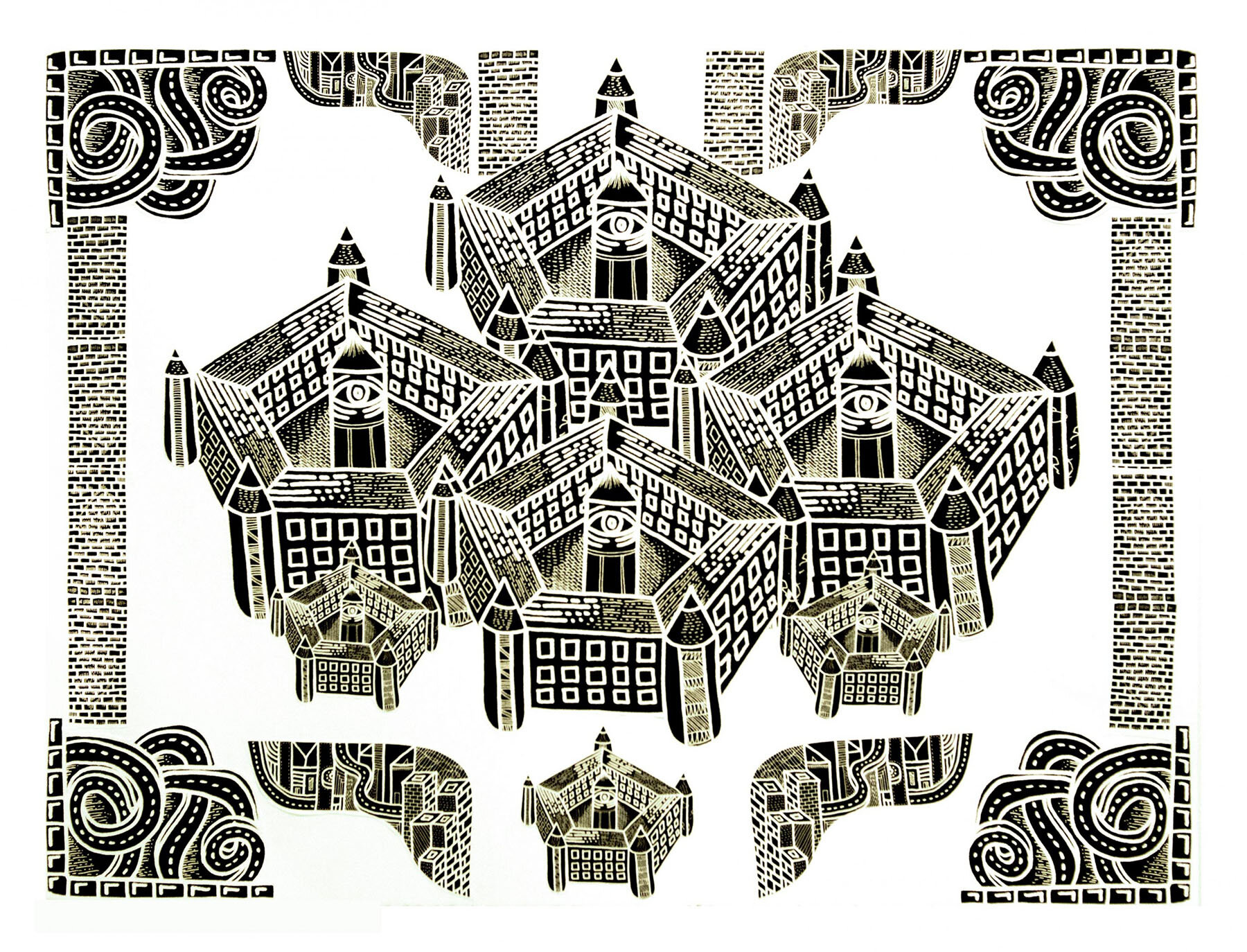

Panopticons by Jay Crum (courtesy Celeste).

Ifat Gazia

The first dream I remember is almost 24 years ago, when I was four, and I still remember it vividly. I saw myself with my father in front of a beautiful house — something I had never seen before in real life. There was a huge tree with multicolored jewels hanging from its branches. Unlike the norm in Kashmir to have fences and huge brick walls around the houses, this house in my dream had none. My father was happy and so was I. Suddenly a flock of animals passed down the street, accompanied by huge crowds of men. These men were different, they were outsiders and looked violent. In no time they killed my father in front of my eyes. I woke up, shivering and crying. I told myself, no matter how beautiful a house, there should be a wall surrounding it.

This was a violent dream, as violent as the reality around me. This was the time when we had barely recovered from months of homelessness and violence, after our entire town was burnt down by the Indian army and we were uprooted, displaced and forced to live like homeless people on the outskirts of the same town. It was an “internal exile”. There was an invisible wall of oppression and authority between the town and the rest of Kashmir. No one was allowed to come into the town, nor were we allowed to leave. For months those of us who were not able to escape the borders of our town either lived in camps or shared houses left behind by those who were able flee in haste. To this day I fail to understand why we were not allowed to leave, although we decided to do so later.

Leaving behind one’s home and belongings is a hardship. It’s all you know and all you belong to. I wonder why we were forced to not only live that life of scarcity, fear and deprivation but also witness the spectacle of destruction, when the centuries old Sufi shrine in our town alongside thousands of houses turned to ashes in front of our eyes.

I remember watching it with hundreds of other people from a hill. I remember the black burnt pages of books flying in the air. I remember people crying and wailing. In that very moment, people of my town lost not just everything in terms of material possessions, but also the relationship they had with that space and its people. A closely-knit network of houses and inhabitants was now scattered across the boundaries of the town that was mostly otherwise covered with agricultural land. I am reminded of the lines from an essay by Njabulo S Ndebele, called “Home for Intimacy”:

“Time was not distance and speed, but the intensity of anxiety. The longer the distance the more intense was the anxiety. Nothing else existed between A and B but mental and emotional trauma.”

When we returned home after the fire, our house was still standing there, possibly because it had a lot of free land around it which created a gap between the fire and our house. But the walls of our house were barely standing. They were bullet-ridden walls. They had become porous and one could see inside out. There was no sense of privacy left anymore. The armed men had vandalized our belongings, our furniture, our clothes and even our photographs, our only window to our past. The walls of that house were a testimony to our pain and agony. Between those walls, my father taught me how to lie flat on my stomach so as to not get hit by a bullet during cross firing, which was a common occurrence, before we were asked to evacuate. When we returned, those walls nevertheless provided a sense of security to not just my family but four other families, related to my grandparents, who had completely lost their homes to fire. Within those four walls, these five families created their own boundaries and called it home. There were five households dwelling inside my tiny home. The boundaries were flexible and expandable, almost as if my home was pregnant. There might not have been privacy, but there was a sense of security.

My town took years to rebuild. Some people are still rebuilding, while others will never be able to return. For many — for my parents certainly — it was as Ndebele describes, “Returning home, I did not find any home, but then again, I have returned home.” Their generation was displaced forever. The only thing that added respite to their changed lives was to talk about their old dwelling places and the sense of belonging they had with those spaces in that particular time. I imagine my father and others saying something similar to Ndebele:

“I dream that my children can build homes of the kind that eluded me; homes that can never be demolished by the state in order to make memories impossible.”

But unfortunately, it only got worse for us from then on. In recent years, hundreds of homes have been demolished to the ground by Indian security forces, as a form of collective punishment for sheltering local rebels. Indian soldiers can also force a family out of their property, calling it a strategic site. There is no fighting back.

Political map of the Kashmir region as of November 2019, showing the Pir Panjal range and the Kashmir Valley or Vale of Kashmir, and Azad (Free) Kashmir.

Kashmir is a disputed territory, two thirds occupied by India called Jammu and Kashmir and one third with Pakistan called ‘Azad’ Kashmir. A small chunk of Kashmir is a cold desert and is not inhabitable, though it is occupied by China. It is called Aksai Chin. Azad in Urdu means free and it is a word that I have heard often from childhood. One of my earliest memories is of an all-women protest after the fire in our town. Women were wailing, crying and chanting slogans. I was there with my mother, holding on to her leg, so that I wasn’t separated from her. I kept looking up at her face, full of sweat. The May sun was shining bright on her head. I wasn’t able to look at her properly. Her scarf was tied behind her ears and she chanted, Hum kya chahte, Aazadi — “What do we want? Freedom!”

In Kashmir there are all kinds of walls, metaphorical and physical. Throughout my school life in Kashmir, there was just one wall, a barbed wire wall, that separated my high school from the military camp. My school was on a hill but towards the bottom. The military camp was atop the rest of the town, keeping a watch on everything and everyone. Military camps in Kashmir are omnipresent. Every morning we would trek for at least half an hour to get into the premises of my school. What was between my home and the school was a hospital and a graveyard with no end in sight. Some of my family members are also buried there. In fact, our school did not have a playground, so we would actually eat our food and play hide and seek within the graveyard premises. There was no visible boundary between the school and the graveyard, between life and death.

My school was relocated to this hill after the original building was also lost to the town fire of May 1995. It was my first school. My first education came from that single story building made of mud walls, with hardly four classrooms and two makeshift toilets. It was hardly 50 feet away from the shrine and located within a busy town market. During my initial days at this school, I overcame the fear of being caught by a teacher and decided to run away back to my mother. I remember it like yesterday. The wooden door of the surrounding mud wall was open, I held my bag to my chest, and started running, running down the stairs, crossing the roads and only stopping when I was home, almost a mile away from the school.

During higher secondary school, there was a tall brick wall, covered with concertina wires and broken glass. It was the kind that has watching pickets on top. The feeling of being watched all the time makes you question your very existence. Am I not human enough? The Indian military creates its own walls between themselves and the people, the walls the establishment creates between people of different areas in Kashmir, turning Kashmir into a panopticon. They can see everyone while Kashmiri people cannot see each other. There are barriers of roads, of curfews, of violence, shootings and even barriers of language. I have always tried to understand the meaning and problem behind these walls and never really succeeded. And to top it all, a wall of miseducation and disinformation has always covered Kashmir, keeping it hidden from the foreign imagination. Whatever happens there, mostly stays there.

Kashmir is the largest militarized land on earth. It has been under Indian occupation since 1947. In spite of being one of the oldest unresolved conflicts on the face of earth, where human rights violations like torture, enforced disappearances, rapes, arrests etc. have become countless, the world barely knows about it. A plebiscite was promised to the people of Kashmir when it acceded to India and Kashmir was allowed to retain some form of autonomy. The plebiscite never happened and the autonomy was revoked on August 5th, 2019.

On that day, the meaning of everything around us had changed. Kashmir was cut off from the world with all means of communication completely blocked and a physical curfew imposed to restrict any kind of movement. On Sunday night, August 4th, 2019, a doctor friend of mine called me saying we should buy any essentials, as she heard rumors that there might be a curfew starting Monday. Curfews in Kashmir were not unusual, but what made this one particularly frightening was that thousands of military men were further flown into an already heavily militarized region, while Indian tourists, pilgrims or students were asked to either leave Kashmir or were evacuated. On Monday morning I woke up to a pin-drop silence at my in-laws home. Nothing was moving on the roads and our mobile phones could no longer find a cellular network. It felt like life had completely stopped. We were lost, as if we didn’t exist on the map of earth anymore.

You can’t imagine what it feels like to live with absolute lack of any form of communication. Our TV only showed selected news channels that peddled only an Indian narrative. Ten days later, I made a tedious journey to the airport without seeing my parents. The airport did not look like a Kashmiri airport anymore. There were hardly any Kashmiris but only military personnel being flown in. I remember my husband whispering in my ear, “We will never return back to the same Kashmir again.” For months to come there was an invisible wall between me and my family. There was a silence between me and my home, the silence that operated as distance. Our existence had been muted with oppression and the silence was instrumental to the interpretation of refuge, dwelling and belonging.

During the day I would scroll down my Twitter homepage for any news coming out of Kashmir and prayed I didn’t see an acquaintance or relatives named among the thousands of people arbitrarily arrested or even killed. At night I saw dreams projecting the political reality of Kashmir, I saw houses on fire, I saw people running in fields, trampling each other, I saw military trucks chasing me. In these dreams my family didn’t exist anymore, and I dreamt of endless conversations with my mother, in which I would share everything that I would normally do in a phone conversation. I dreamt of pain, agony, yearning and loss. As Edward Said described it, there was an “unhealable rift” between us.

I landed in the US and for seven months to come, I communicated with my family through third parties. Some landlines were restored in Kashmir later in August, but I was not able to call them from the US. Ironically, after mobile phones were introduced in Kashmir in late 2000s, people cancelled their landline subscriptions. There are barely any families that still have a landline. I would call a Kashmiri friend in another part of India, they would call that landline number and if I got lucky, one of my family members would be around and I could leave a message for a minute or two. It was in February 2020 when 2G internet was restored in Kashmir and I saw my parents on a hazy 2G video call. In all those months, my resolve to fight to overcome the injustices Kashmir has suffered only grew stronger.

I have not been able to go back home since August 2019. I am thousands of miles away, yet there are no barriers between me and my home in my dreams. Every dream takes me to Kashmir, to the people I knew there. I hardly see myself in America. Sometimes, I see dreams within dreams. Recently I dreamt I was Kashmir but when I woke up, I was in America, then realized waking up in America was a dream and I w

as actually in Kashmir. But eventually I opened my eyes here, in America. It reminds me of what my professor Stephen Clingman once said, that one had “never really left, never really arrived, somewhere in the middle.” I never thought how much yearning I had for my home and I would have never been able to imagine it until I was forced to live here without an immediate prospect of going back.

Although I have a country I call my own, I do not have papers to prove that Kashmir is a country anymore.