Select Other Languages French.

The 18th Istanbul Biennial tries to find its footing amid accelerated urban and political change.

Istanbul is known as a city of cats. This makes The Three-Legged Cat a relatable title for the 18th Istanbul Biennial. The title refers to the Biennial’s three phases but also points to the fact that a three-legged cat is a hurt animal. The project unfolds with the 2025 exhibition and public program (the first leg), an Academy and series of public programs in 2026 (the second leg), and concludes in 2027 with an exhibition and public program (the third leg). Its first iteration, however, cannot fully find its footing yet.

Perhaps this is to be expected from a three-legged cat, a fitting metaphor for the state of the world, which tenaciously limps along, maimed and unstable, and yet, at its best, is still full of life and fight.

Curated by Beirut-based Christine Tohmé, the Biennial resonates with the disquiet in Istanbul and the world at large. Tohmé is a doyenne of the Lebanese art scene and no stranger to producing art projects and developing artistic infrastructure against the odds (wars, financial collapse, and a failed state). Turkey, with its flailing economy and President Erdoğan’s repression of freedom of speech and opposition, mirrors the authoritarian bend of global politics. In fact, he had Istanbul’s popular mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, of the center-left CHP opposition party, arrested in March 2025; the mayor remains in prison as of this writing, where he faces up to 2,340 years, according to Le Monde.

Christine Tohmé was only appointed in October 2024, following a particularly restive period for IKSV, the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts that oversees the Biennial. This might explain the more compact nature of the Biennial (47 artists), dearth of new commissions, and low participation from Turkish artists in the exhibition. Originally, the international advisory board had selected Turkish curator Defne Ayas to spearhead the 18th edition in 2024. IKSV, however, rejected the recommendation in favor of former Whitechapel Gallery director Iwona Blazwick, herself a longstanding member of the Biennial’s advisory board. In 2015, Ayas faced controversy for including a text in the booklet of the Turkish Pavilion for the 72nd Venice Biennale, featuring Turkish-Armenian artist Sarkis, because it contained the term “Armenian Genocide.” Besides the Istanbul Biennial, IKSV is also responsible for the Turkish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The Pavilion’s booklets were never distributed but this episode illustrates the complex balancing act an independent organization like IKSV must perform in relation to national and nationalist politics.

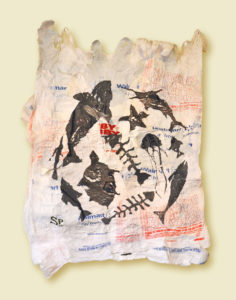

In addition, IKSV has to contend with — but inevitably also plays a part in — the rapid gentrification of the Karaköy district, home to the main Biennial venues. The development of Galataport, a heavily policed open air shopping mall on the waterfront, and the Karaköy entertainment hub, has meant the demolition of many historic buildings. Some have been kept, restored, and turned into polyvalent event spaces. So too the Galata Greek School, a mainstay of the Biennial. In its refurbished state it allows for crisp and museum-quality exhibitions, yet part of its historic and urban biography has been forever lost in the process. The artworks in the Greek School focused predominantly on extractivism and eco-critical issues, such as South African artist Lungiswa Gqunta’s landscape installation “Assemble the Disappearing” (2024-25); Saudi artist Ayman Zedani’s salt and sound work “Between Desert Seas” (2021), which looks at endangered Arabian Sea humpback whales and ocean salinity; and Mexican artist Naomi Rincón-Gallardo’s hilarious and festive anti-mining video “Opossum Resilience” (2019) of dancing opossums, water guardians, and fertility goddesses. There is a fine line to walk between capital extraction of natural resources and that of real estate. The Biennial’s media campaign foregrounded the venues rather than the artists. On the one hand, this calls attention to an urban heritage under threat of erasure, or, in the Biennial’s case, venues being preserved (garden of the former French orphanage), renovated (Galata Greek School, Zihni Han, Muradiye Han), or “activated” (Meclis-i- Mebusan 35, Elhamra Han, the cone factory). On the other hand, Richard Florida’s thesis that the creative classes rejuvenate urban centers while simultaneously marginalizing working- and middle-class residents lingers uneasily over these sites. Conceptually, the Biennial engages only minimally with these topics. There is a paucity of site-specific works and of projects that are more embedded within the fabric of the city and speak to these urban challenges and dangers. This paradoxically makes for a biennial that feels divorced from its surroundings, rather than informed by it.

There are notable exceptions. Chilean artist Pilar Quinteros’ brilliant new commission “Working Class” (2025) is based on Turkish sculptor Muzaffer Ertoran’s the “Worker’s Monument,” which since its installment in 1973 at Tophane Park was repeatedly vandalized. The socialist-style statue, a laborer with a sledgehammer, was originally commissioned by the CHP party as a tribute to the almost million Turkish migrant workers who had left Turkey for Germany since the 1960s. Now only the torso is left. Quinteros hones in on the damage rather than on repair and loosely strings together multiple cardboard copies of the statue’s missing limbs, head, and hammer. Placed above a mirror, they are a floating composition of repetitive dismemberment. A mockumentary accompanying the installation shows an actor playing a neurotic Ertoran in his workshop, endlessly directing his team of young women to produce ever more cardboard body parts. Quinteros smartly brings together issues of artistic and other labor in the face of political and urban change. A few steps away, the slick new Istanbul Modern building and commodified bling of Galataport loom large over what is left of Ertoran’s monument to the working classes.

At the garden of the former French orphanage, Palestinian artist Khalil Rabah presents the only outdoor work and makes a poignant comment about the endurance of life amid ruin and exile. For his site-specific installation “Red Navigapparate” (2025), the artist planted a hundred olive, fruit, and nut trees in red oil barrels that are each placed on red wooden pallets. A water channel with a red pipe runs parallel to the trees and a red pallet jack mounted on a marble pedestal accompany this makeshift orchard. These trees are not rooted in the soil of a homeland, rather they have become moveable entities; the pallet jack at the ready to displace them once again. It is impossible to uncouple this installation from Israel’s obliteration of all arable land in Gaza, settlers routinely destroying olive and fruit groves in the West Bank, and the multiple erasures and displacements of the Palestinian people, historical and current. The dilapidated orphanage exudes loss, but its blooming garden preserves a sensibility of refuge. Rabah’s trees can still thrive and bear fruit here. At Galleri 77, Egyptian artist Mona Marzouk addresses the topic of flourishing differently. Her room-size mural “The Cannibal Paradox” (2025) explores the tensions between human and nonhuman shelter in a fantastical way. In deep hues of red and pink, Marzouk’s drawings meld avian anatomy with Islamicate architecture. Beaks, claws, and wings protrude from domes and arches. These bird-buildings are monstrous, enthralling, and unmistakably alive.

The above-mentioned works resonate strongly with Tohmé’s curatorial framework, which emphasizes themes of futurity and survival. However, with the whole world on fire and trudging through serial crises, this premise might be too broad to leave an impactful mark. Are we not all trying to survive and forge a path into the future? It feels as if this first iteration is only beginning to lay the groundwork for what might follow in 2026 and 2027.

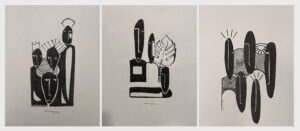

Still, for a relatively small edition there are many strong works. The Biennial convinces most when it becomes specific and sifts through the rubble of the 21st and 20th centuries to find a horizon. This will always be an imperfect endeavor, because like with the three-legged cat, the injury remains. The most powerful artworks acknowledge the wound and advocate play (Marwan Rechmaoui), bodily movement (Jasleen Kaur; Rafik Greiss; Haig Aivazian; Karimah Ashadu), growth (Stéphanie Saadé), and bearing witness (Sohail Salem; Abdullah Al Saadi; Ola Hassanain).

In addition, modest gestures of defiance go a long way. Under Erdoğan’s authoritarian nationalist and conservative agenda, LGBTQI+ communities have increasingly come under attack and are portrayed as a threat to family values. Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari’s series of small acrylic paintings Olive Green (2020) depict male wrestlers engaged in oil wrestling, an ancient sport popular in Turkey, the Balkans, and Iran. Made during the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown, when bodily proximity of all kinds was curbed, the series celebrate male intimacy. Given Zaatari’s queer-coded early videos and his archival work on masculinity and sexuality, these delicate paintings sit lovingly between the homosocial and the homoerotic. With their suggestive poses and scantily clad entangled bodies, there is enough libidinal desire invested in these paintings to make a prude blush and a bigot object. In these moments The Three-Legged Cat leaps over its constraints and shows its teeth. A promise, one would hope, for what is to come.