Staff Report

The National Museum of Qatar (NMoQ) is considered one of the great wonders in the world of museums. When it opened in 2019, architecture journals praised the $434 million, 430,000-square-foot structure designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Jean Nouvel. Curved discs, dramatic intersections, and cantilevered angles — described by David Belcher in the New York Times “as if the teacups on the Mad Tea Party ride at Disneyland had spun out of control” — were inspired by the desert rose. These flower-like crystalized minerals, sculpted by wind, salt, water, and sand, take thousands of years to emerge from the shallow salt basins beneath Qatar’s soil.

The iconic museum building is composed of interlocking disks of different diameters and curvatures that surround the carefully restored historic palace of Sheikh Abdullah bin Jassim Al Thani (1880-1957), son of the founder of modern Qatar.

The NMoQ houses 11 permanent galleries, which have been arranged chronologically, beginning with the period before humans inhabited the Arabian Peninsula and leading up to the present day. The story of the kingdom’s evolution and development is told on a grand scale, through exhibits that include archaeological and heritage objects, jewelry and other treasures, as well as manuscripts and documents. Specially commissioned artwork is exhibited alongside bespoke models fashioned by artisans and craftspeople, of boats, buildings and archaeological sites, of animals and creatures of the sea.

Sweeping video and films, on curved walls and surfaces, are accompanied by immersive soundscapes provided by multichannel sound systems, digital audio platforms, and hidden smart loudspeakers. Some galleries use distinctive aromas to enhance the stories of the exhibitions.

In the gallery devoted to “The Formation of Qatar,” the film The Beginnings (2018), by Christophe Cheysson, presents museumgoers with a reimagining of Qatar’s geological formations and early life-forms, such as the Qataraspis deprofundis, a species of armored fish. Also on display in the gallery are ancient fossils and plants from seven time periods.

Another of the permanent galleries in NMoQ is “Qatar’s Natural Environments,” which features models and exhibits about indigenous plants and animals, from the Arabian oryx and the sand cat to the deathstalker scorpion and the nine-meter-long whale shark. In the kaleidoscopic film Land and Sea (2017), Cheysson, co-directing with legendary filmmaker Jacques Perrin, shows a 50-meter-wide flock of birds filling the sky, as schools of fish swim through the deep blue seas.

On the wall of the gallery devoted to the kingdom’s archaeology, ancient rock carvings from Al Jassassiya and Al Kassar have been reconstructed. The film Archaeology (2017), by the Iraqi-British artist Jananne Al-Ani, combines aerial views with intricate close-up images of objects from pre-historic times to the Bronze Age and beyond.

The NMoQ’s collection deftly shifts from the country to the people. “Life in Al Barr (Desert)” gallery, for instance, includes a bait al-sha‘r (tent of goat-hair), displays of sadu weaving, and clusters of cooking utensils. In this gallery’s immersive soundscape, poetry being recited can be heard. The pungent aroma of brewing qahwa (coffee), lingers in the air. The Mauritanian-born Malian film director Abderrahmane Sissako made the film Life in Al Barr (2017) to reveal the daily cycle of desert life. Another of his films, Al Zubarah (2017), has been included in the gallery devoted to life on the country’s northwestern coast, which features a large-scale model of the archaeological site of Al Zubarah, Qatar’s first UNESCO World Heritage site.

In the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the walled port of Al Zubarah, founded by Kuwait merchants, served as the gateway to the rest of the Arabian Peninsula and points farther afield, such as India, Western Asia, and East Africa. The port flourished through trade and pearl-diving, activities that were key to the formation and development of small independent principalities along the peninsula. These had sprung up outside the Ottoman, European, and Persian empires, and eventually led to the emergence of the modern-day Gulf States.

In the “Life on the Coast” gallery, the 2014 film Nafas (Breath) by the Indian-American filmmaker Mira Nair, explores the hardships of pearl fishing. Another gallery, “Pearls and Celebrations,” features one of Qatar’s national treasures, the Pearl Carpet of Baroda. Commissioned in 1865 by the Maharaja of Baroda Khande Rao Gaekwad, the Pearl Carpet of Baroda glows with the luster of more than 1.5 million Gulf pearls, emeralds, diamonds, and sapphires.

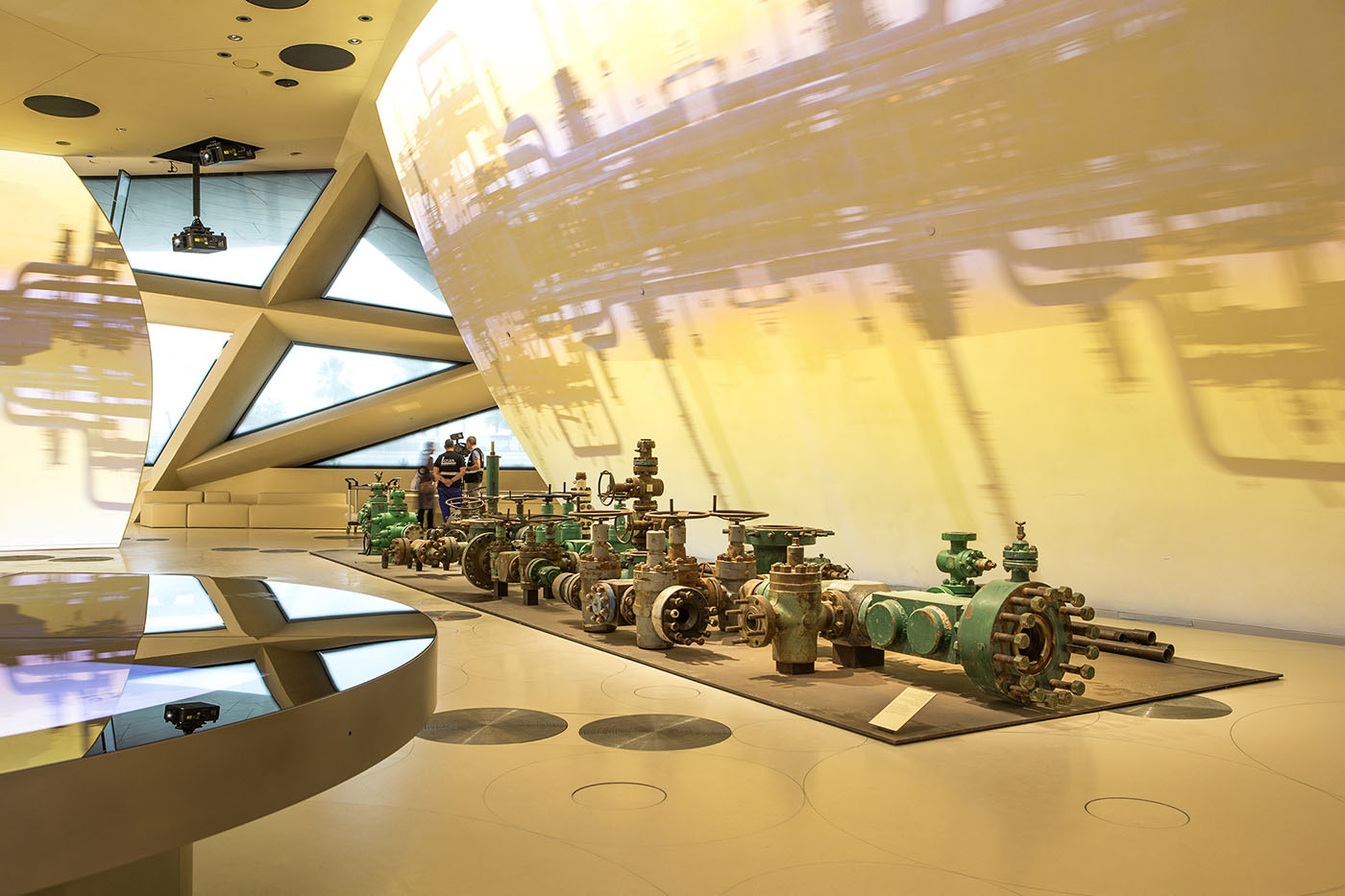

Since the 20th century, oil has come to be as precious to the kingdom as pearls. After its discovery in 1939 in Jebel Durkan on Qatar’s southwestern coast, a sparsely populated desert country became a magnet for a workforce from around the world. This vivid transformation is captured by The Coming of Oil (2017), by video artist Doug Aitken, an impressionistic 360-degree installation film.

Another gallery is devoted to the construction and development of Qatar’s capital city, Doha, from 1972 to 2013, under the reign of Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, followed by that of his son, Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani. A 5-meter-diameter wooden model of Doha with a multi-user interactive wall enables museum visitors to explore archival images related to the country’s development over a forty-year period. It shows how revenues from oil and LNG (liquefied natural gas) made dramatic urban development in Doha possible.

The gallery also features an oral history film about the Father Emir made by Moroccan-Iraqi-British director Tala Hadid, Qatari filmmaker, art director Rawdha Al Thani, and Amal Al Thani, alongside a video art installation about LNG. Alchemy, 2019, the permanent installation by John Sanborn, is displayed on 30 high-resolution monitors.

The tour of the museum interior concludes with the gallery “Qatar Today,” which highlights the achievements of the current Emir and the challenges the country faced during the blockade imposed on Qatar in 2017.

Outside, on the NMoQ extensive grounds, are the public artworks commissioned by Sheikha Al Mayassa bint Hamad Al Thani. These include: Flag of Glory, a group of hands united in holding Qatar’s flag, by Iraqi artist Ahmed Al-Bahrani; On Their Way, four nomadic camels by French artist Roch Vandromme; and Gates of the Sea, inspired by petroglyphs, ancient rock art, found at Al Jassasiya.

Peace Bench, in the museum’s outdoor Baraha souk, is made from 100 percent recyclable aluminum, and was commissioned to mark the 50th year of industrial collaboration between Qatar and Norway, in 2019. Norwegian architect and design group Snøhetta and Vestre designed and manufactured the bench, which was given to NMoQ by the Nobel Peace Center and Norwegian company Hydro. The first edition of the bench can be found outside the UN headquarters, in New York City.

The National Museum of Qatar is a repository of history, art, technology, and culture. It not only challenges perceptions of visitors to Qatar, but gives people living in the kingdom a greater understanding of the world around them, and the inspirational collaboration between humans and nature over many millennia.

1 comment