Select Other Languages French.

Veteran writer-director Annemarie Jacir’s Palestine 36 is a cinematic tour de force. With its narrative-shifting paradigm, it encourages viewers to embrace a broader understanding of the Palestinian experience.

Filmed during and in spite of post October 7th violence and the Iran-Israel conflict, Palestine 36 set at the time of the 1936 Palestinian uprising against British colonial rule. In his book, Palestine 1936, Israeli historian Oren Kessler observed that, “The Great Revolt was the crucible in which Palestinian identity coalesced. It united rival families, urban and rural, rich and poor, in a single struggle against a common foe: the Jewish national enterprise — Zionism — and its midwife, the British empire.”

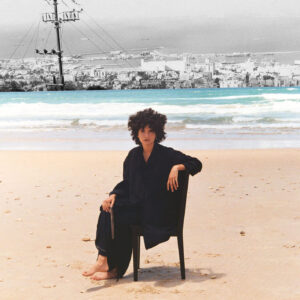

What makes Jacir’s powerful historical drama so effective are the very personal stories it follows of Palestinians swept up in the general strike and resistance against British colonialism. Yusuf (Karim Daoud Anaya), a farmer from a village near Jerusalem, works in the city but returns to his ancestral lands at night to defend its confiscation by Zionist settlers. Saleh Bakri plays a disenchanted Jaffa port dockworker who joins the rebel movement. Making her screen debut, Yafa Bakri stashes away an heirloom gun in hopes of defending her family from the British military’s raids. Shot on location in Palestine and Jordan, Palestine 36 includes rare archival footage and features Hiam Abbass (Succession), Jeremy Irons (Reversal of Fortune), and Liam Cunningham (Game of Thrones). This is Annemarie Jacir’s fourth feature, following Salt of This Sea, When I Saw You and Wajib; it is the Palestinian entry for Best International Feature at the Academy Awards. Jacir spoke to us by phone from her home in Haifa.

Hadani Ditmars: Your film — so full of passion and pathos and wonderful performances, is also incredibly timely, especially with this bizarre neocolonial proposal to have Tony Blair as the de facto “king” or viceroy of Gaza.

Annemarie Jacir: Yes, we are still in a colonial moment. We have never been out of the colonial moment, unfortunately. People always use this term “postcolonialism” and it mystifies me. I wish there was postcolonialism but no, we’re still in that moment.

TMR: What was your initial inspiration for making this film?

JACIR: I’m a history nerd and I’m just fascinated by the Palestinian uprising of 1936. I think it’s the critical moment in our history that is almost never talked about, because we always start with the Nakba for some reason. It’s really important that we talk about this moment more than a decade before 1948, because of course it sets the stage for everything that comes after; for the loss of Palestine. It’s amazing to me that the British were doing what the Israelis are doing now. Not just the obvious torture and waterboarding, but also collective punishment like blowing up people’s houses, sending people to detention camps, and even building a wall. The mastermind of the wall was a man named Charles Tegart, and so there’s a character in the film with the same name, played by Liam Cunningham, and a scene in which he is outlining the proposal for the wall — how long it is, how high, and how far it will reach. Its main function was to separate Palestine from Lebanon and Syria. There’s a lot of pride in the fact that we had arguably the longest and largest revolt and strike (from April to October) against British colonialism at that time. It was a general strike. Everybody was involved, from port workers to railroad workers to newspapers.

TMR: You were filming during some very trying times. How difficult was it to produce?

JACIR: We had to stop and start four times with everything that was going on, because it just got worse and worse. My producers needed to deliver the film, and we had financial obligations; they wanted me to shoot, and so I was getting proposals to film in other places, including Malta, Greece, Morocco, and Cyprus. I kept refusing, I was very stubborn about it. I just could not bear the fact that we had to shift so many scenes out of Palestine*. It was so devastating, because the film was so much about the land; I just couldn’t conceive of filming scenes set in Jerusalem or Jaffa somewhere else and pretending it was real. We lost a lot of money because of that, and we had to shrink the crew. Some actors were denied entry, or their agents wouldn’t let them come because they live abroad, they were like, “no way are we going to send our client to make a film in Palestine right now.”

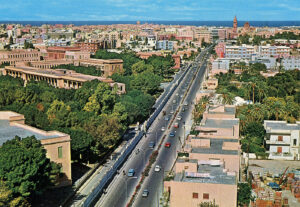

We filmed in Jordan and then we came back in November. But we would have to stop production when there were missiles or alarms, and we had to go running into the shelters. Getting insurance was a nightmare. But even when we had insurance it wasn’t safe. We restored a whole village near Nablus before shooting the main village scenes, but [then] we had to go elsewhere because the whole area was overrun by armed settlers. So a lot of the village scenes were filmed in the north of Jordan, where it’s very green and close to the Syrian, Lebanese, and Palestinian borders. They feel like very fake borders in fact because the land is the same land. The scenes that were shot in Palestine were the scenes in Jerusalem and Jaffa and we shot some interiors in Bethlehem. In fact, the exterior shots of the main characters’ house in Jerusalem were shot in Katamon (once a mixed Palestinian Christian, and Muslim area west of Jerusalem that was ethnically cleansed in 1948).

TMR: What was it like emotionally for you to make this film during a genocide? How did you get through it?

JACIR: I don’t know. It was devastating for everybody. The cast and crew, a lot of them have family in Gaza. We filmed in the West Bank where it’s total apartheid now, and you have the army coming in and arresting people. By the way, a number of our crew members are still in Jordan because they are young men, and they could be grabbed and detained at any minute for nothing. Emotionally it was really hard, and I think I’m still not able to process all of it because part of me just sort of had to put blinders on. I couldn’t look at social media or I wouldn’t have been able to get out of bed in the morning. The scene in the village — without spoiling the ending — with the British army, it was very real for the cast. The woman who played the young girl Afra’s mother, Yafa Bakri, it was her first acting role. But she was not acting. She was so emotionally plugged into what was happening around us, it was very hard for her, and she was really distraught and at one point she actually passed out on set.

TMR: On the other hand, was making this film part of your emotional survival?

JACIR: I love that you just asked me that. I think it was — it was and maybe that’s why I became so stubborn about coming back to Palestine and finishing the film in Palestine. All of us to just keep going because we felt so hopeless and making the film was something concrete we could do. It was a way of maintaining our presence — the fact that we are here and we do things with love, and we will not disappear. My father is in his 90s now and it’s like the same thing is still going on. I also think we’ve felt in these last two years more alone than we ever have. I can’t believe this is still going on after two years and getting worse. At the same time the other side of that is we’re seeing people speaking out. We’re seeing people on the streets all over the world protesting and it’s really heartening.

TMR: How much research did you do into the Arab revolt, and what were your main sources?

JACIR: In terms of academia, there were the works of a few people. Charles Anderson and Matthew Hughes both are British Palestinian historians. Johnny Mansour who lives in Haifa actually read the script and helped me. I also read work by Israeli historian Ilan Pappé. Also, Ghassan Kanafani was a little obsessed with the revolt of ‘36 — as I am — and wrote a lot about it. And then there were actual documents in the British archives. There’s a character in the film called Thomas who is the High Commissioner’s secretary. He’s based on a real person who left diaries of his time in Palestine. He was very upset by what happened. He came with good intentions thinking the project was one that was beneficial for the local population. As time went by, he started to realize that it was a failure, and he ended up quitting his post. The British archives were an incredible source of footage. They filmed everything! At first it was just part of my research but then I started cleaning up and colorizing the archival footage.

TMR: I wonder why so many historians — Palestinian, Israeli, and British — are obsessed with the 1936 revolt? Perhaps because it was before things went really wrong, when maybe there was still a chance that things could have gone differently?

JACIR: Yes, I totally agree with that. I think that’s what attracts me about the period, too, because there was a lot of possibility. Things could be really different today had it gone another way.

TMR: You started working in documentary film with Like Twenty Impossibles. Are you a documentarian at heart, do you think? There was an interesting mix of fact and fiction in this film.

JACIR: I love documentary film. I started there, it’s true, but I didn’t like making documentary films. Although I had wanted to be a documentarian, it wasn’t for me. I found myself going the other way. There’s something I really like about the freedom of fiction in feature filmmaking. I feel like with documentary I don’t have that freedom because you’re dealing with real people. When I try to make documentaries, I feel myself caught up in too many ethical questions like, for instance, “how can I take this person’s life story into an editing room and cut it up and choose what is important and what’s not?”

TMR: Was the village in the film based on Al-Bassa village (ethnically cleansed in 1936 by the British army)? Can you tell me about that?

JACIR: Yes, it was. There were many massacres in ‘48 all over Palestine, but there seems to be less awareness of what the British did before then. I was shocked to learn that something like this had happened 10 years before the Nakba. It didn’t start with the Israelis. There was something being set up. There was definitely a system of control that was set up here and the Al-Bassa massacre is very much part of it. So, the village in the film is definitely inspired very specifically by that story in Al-Bassa, but it also references Lifta village outside of Jerusalem because Al-Bassa is of course way in the north and I was interested in a village that was near Jerusalem — walking distance from Jerusalem, where women could walk to the market or you could take a bus. Where there was a sort of back and forth between the two places and there was a relationship between city and village. Lifta is also one of the few villages that’s still partly intact, architecturally. Most of the houses there are interesting because there are two-story houses and the Israelis now, they are starting luxury housing projects there. The village near Nablus that we restored before filming, that was shut down by settler violence, was one of the few villages still standing in the area. Some of the original villagers actually lived nearby and they became part of the project and were restoring it with us, and they knew the histories of the houses. We also planted in the village. We planted all the things that Palestinians used to plant while we were in preparation for the film. We planted cotton fields and tobacco and all these things that we know Palestinians are not allowed to plant anymore. In the end, we couldn’t use that village because of the settlers — it’s totally surrounded by settlements, and they’ve got their eye on it. But the thing that makes me feel good is that the villagers who were helping when we were restoring it continue to use it. They’re working there and they’re living there, and some of the crops have continued that we planted — so there is a silver lining.

TMR: It’s interesting that there is no contact between the Palestinians and the Jewish settlers — except for the violent confrontation when Yusuf’s father is shot — it’s all between the Palestinians and the British. And that key line by Captain Wingate (who says “The Zionists provide the key to preserving the empire”) underlines that idea that both peoples were tools of empire. Was that a deliberate choice in your screen play?

JACIR: I was really interested in the British-Palestinian story. It was important for me to show the Jewish refugees were coming here for safety as so many other communities had, like the Armenians and the Bosnians (in the 19th century). I wanted to point the finger at fascism in Europe — showing that Jews were fleeing from this awful thing and it had nothing to do with us.