This India is a place saturated with preemptive surveillance driven by artificial intelligence. Old-fashioned journalism, in such a context, is almost passé, and its practitioners, like those of any of the traditional arts requiring human empathy and empowerment, are having a tough time of it.

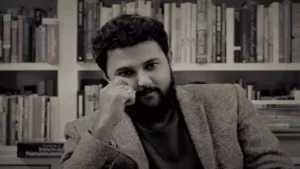

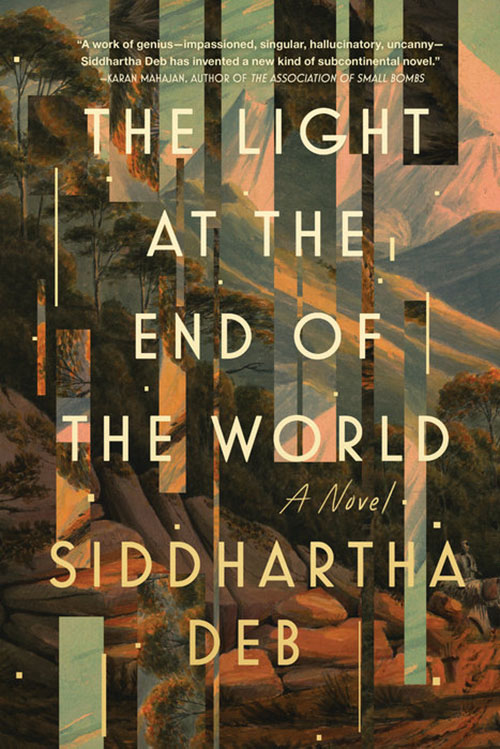

The Light at the End of the World, a novel by Siddhartha Deb

Soho Press 2023

ISBN 9781641294669

Anis Shivani

The Light at the End of the World, by Siddhartha Deb, is a brave novel that demands brave readers. It poses great difficulties in terms of expectations and rewards, in the vein of the tough high modernist novels. Eighteen years have gone by since Deb’s most recent novel, An Outline of the Republic — and it shows, both in the texture of Light, which is very dense and self-involved, and in the all-encompassing emotional sweep, with both the advantages and disadvantages this brings. Its style throws doubt on the novel’s capacity to deal with the mess of contradictions that is modern India. The centrifugal tendency almost brings the novel to a halt during its middle portion, which consists of historical interludes, and the connections are not entirely clear until the end. The novel works best when read as a loose compendium of episodes illustrating the Indian psyche at different points in history, rather than as a linear narrative with tight causal connections between episodes.

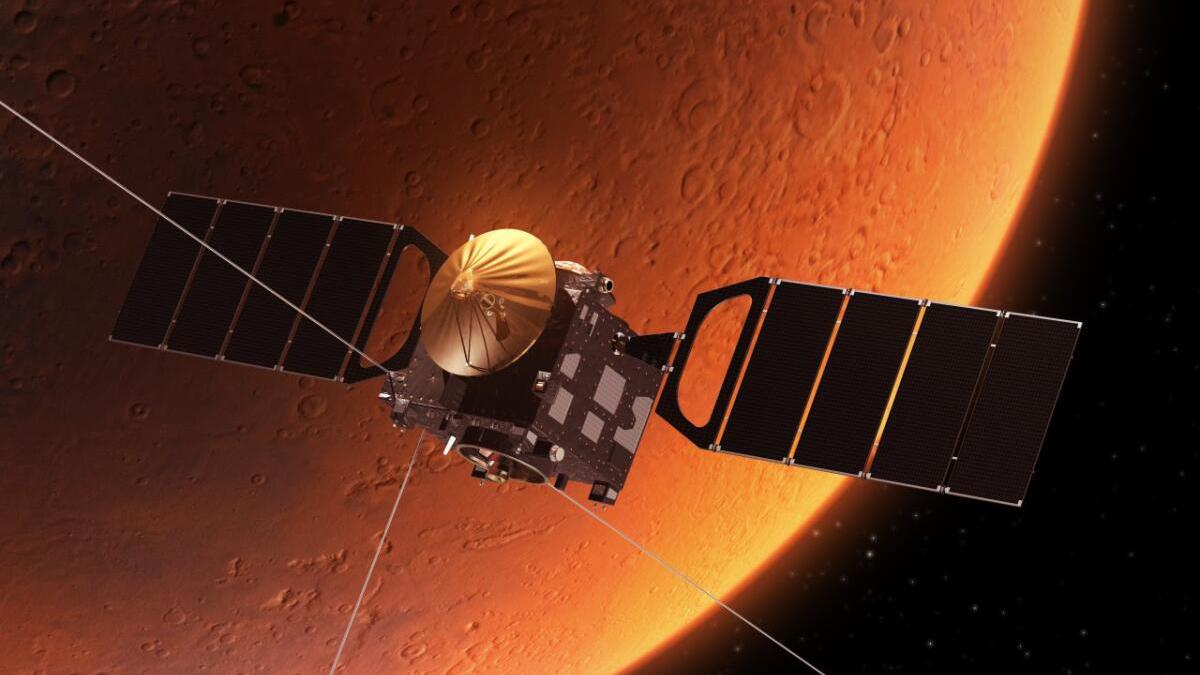

At the start of Light, we meet protagonist Bibi, an ex-journalist whose investigative reports once threatened the apparent invincibility of the state, and who is now distanced from her former connections in the journalistic world. Bibi operates in a perpetual fugue as a staffer at Amidala, one of those powerful image management enterprises so typical of the neoliberal economy. This opening section is set in a New Delhi where rampant neoliberalism is destroying everything virtuous about Indian culture. Here are social media influencers, business tycoons, deep state figures, and censors and spies of all stripes — in short, all the manipulators we have become accustomed to in the 21st century political economy — playing out their schemes for personal glorification, which often merge with nationalism, without the least bit of shame. Extreme poverty, the image of India that persists in the popular imaginary, coexists with extreme wealth. The economy is becoming cashless (in real life, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has in fact implemented the highly controversial policy of demonetization), India has piloted a Mars Mission (evocative of contemporary Indian space pretensions), artificial intelligence is often the subtext of elite conversations, and the fictional Ombani defense labs are developing a superweapon called Brahmastra.

This India is a place saturated with preemptive surveillance driven by artificial intelligence. Old-fashioned journalism, in such a context, is almost passé, and its practitioners, like those of any of the traditional arts requiring human empathy and empowerment, are having a tough time of it. Bibi was once closely linked with a journalist named Sanjit, whose insistence on exposing government and corporate corruption put him “on a trajectory that led ever downward.” We can assume that Bibi, utilizing similar abilities, wrote herself out of a job.

What should we make of Bibi’s character? There is nothing recognizably Indian about her, despite her modest origins. Having delegated the caretaking of her ailing mother in Calcutta to a sister while Bibi pays for the expenses, she has the prototypical millennial’s resigned attitude toward the state of the world, interested as she is mostly in quiet survival. Bibi is also free of any ideological commitment. As the omniscient narrator tells us:

[S]he makes her way through her days like someone picking a path through ruins after a war […] for years now, her evenings have been hollowed out by loneliness, her only companion a derisive voice in her head, lacerating, embittered, a voice that doesn’t want to shut up and that can only be silenced by Bibi’s promises to quit, to give it all up.

Bibi’s newfound apathy is emphasized all the more by contrast with her past relationship, full of courage and authenticity, with the aforementioned heroic reporter, Sanjit. Sanjit enters the narrative through Bibi’s flashbacks, which are occasioned by a request from her boss at Amidala, S.S., that she track him down to defuse the threat to Vimana Energy Enterprises, one of Amidala’s clients, and a leading proponent of India’s technological promise. Vimana’s offices were recently broken into by a man who disappeared without a trace except for the recollections of eyewitnesses that a monkey had fled the scene. The intruder left behind a jump drive containing Bib’s greatest hits — from back when she was an investigative reporter. They include her “story on the detention center [in northeast India], the one on the abandoned Union Carbide factory, [and] that piece on the odd antiquities uncovered by geologists prospecting for minerals in the mountains.” Vimana can easily tell that Bibi was linked with Sanjit, who pursued similar journalistic exposés; corporate leadership wants to get to the bottom of the threat, if there is any, refusing to believe that it is mere coincidence that she happens to be in the employ of their consulting firm.

Bibi has not been in touch with Sanjit for years, but suspects that he may have reappeared from hiding as a blogger named Muktibodh, periodically issuing condemnatory statements such as: “India now is like the United States of a nineteen nineties television series called the X-Files, with aliens and experiments and conspiracies of the deep state.” It wouldn’t be unfair to draw a parallel between Muktibodh, the anonymous blogger, and Deb’s own current standing as an outsider whose harsh opinions would probably no longer be welcome by the Indian state.

Bibi has trouble updating her Aadhar identity card (it exists in reality), and worries about showing up in the national registry as a “D,” or doubtful person. This would also be true of Sanjit and other “anti-nationals,” a term of art currently in fashion with the Modi government. Deb’s emphasis on the pervasiveness of technology is an aesthetic choice that goes well with his extreme emphasis on the corpse-like decay of every street and structure and personality Bibi encounters in her peregrinations throughout the city, particularly the Munirka district. This sentence is typical: “The sour tang of milk hits her when she passes the Wenger’s counter, succeeded by the drift of incense, engine oil, and the stomach-churning smell of piss as she cuts through the back alleys.”

There are hundreds of such passages throughout the novel. Alongside the degradation there is the dreamlike mutability of all things; nothing is as it seems, and everything is likely to abruptly transform into something else. The whole book feels like a continuous dream. One might be tempted to think of Pynchon, Borges, Eco, Bolaño, Ellison, Bowles, or Mann as inspirations, but Deb pointedly refuses to find pockets of illumination. His outright denial of human agency sets him apart from even the most dire modernists. The excessive attention to constantly shifting images of decrepitude and the overemphasis on the powers of technology are of a piece with the way in which manifestations of charisma become crushed by the overbearing reality of the Indian state.

Throughout the novel, Deb discounts the possibility of a knowable future neatly connected to the past. He does this, for example, by speculating rather wildly about the origins of New Delhi Monkey Man: “What if New Delhi Monkey Man was a mutant creature produced by the toxic gas cloud of Bhopal in 1984? What if New Delhi Monkey Man was an extra-terrestrial creature, an alien accidentally marooned on this planet? […] What if New Delhi Monkey Man had time traveled from the past, coming at us from the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857 or from the killing fields of Partition in 1947? What if, while traveling through time, New Delhi Monkey Man came to the new millennium not from the past but from our future?”

New Delhi Monkey Man is a present reality, too frequently witnessed to be discounted as mere gossip, which cannot be understood as a link between past, present, and future. His disjointed presence can only give rise to useless conjecture, making a mockery of both Indian mythology as well as the promised future of technological control.

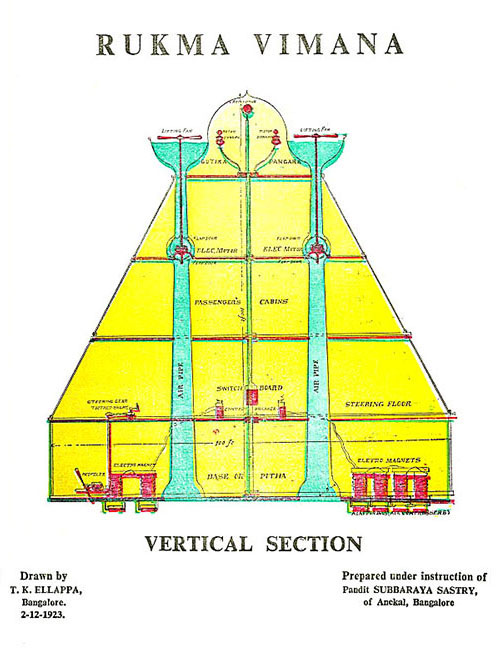

As for the author’s stylistic choices, they are an interesting departure from recent waves of Indian fiction. Rushdie’s magic realism has recently been exploited by American and British-based writers of Indian origin in the familiar multigenerational family secrets saga intertwined with pseudo-colonial history (this is also increasingly true of African writers finding a home in the U.S. and U.K.). Here, magic realism often provides little more than entertainment value, or is offered because this is what is expected of postcolonial writers operating within the West’s publishing ecosphere. Deb’s incorporation of such elements as New Delhi Monkey Man, the frequent appearance of Hanuman the monkey god in various guises, and the Vimana flying craft (which is the central motif in the Partition-era section) is not magic realism as we have understood it via Rushdie, Grass, and Márquez. Nor is it the perfunctory magic realism of today’s young postcolonial writers. Rather, it is a disturbing element of fantasy assimilated into the decay of Indian culture. It works because there is no explanation of decay, the unreal elements of the narrative pointing us in all sorts of futile directions.

It makes sense, then, that it becomes much harder to follow the narrative in the three historical sections that follow, set in 1984, 1947, and 1859, respectively. The prose style in these historical interludes is pervaded by intentional fogginess, and the characters (and their objectives) remain at a distance. Although some reappear in different time periods, such as Bibi in the 19th century section, we are not meant to see them as the same characters as in other occurrences, even if they share a name and certain traits. The blurring of fantasy, reality, dream, image, fact, and myth, amounting to phantasmagoria, stems from Deb’s sharp refusal to provide history with explanatory prowess, as is true of his attitude toward extrapolating the future.

In “Claustropolis: 1984,” set in the socialist, secular, Nehruvian Indian republic that lasted until the 1980s, a professional assassin has been charged by a shadowy boss to kill the whistleblower who wants to reveal the dangerous practices at Union Carbide, an American chemical factory in Bhopal. The assassin is himself pursued, and remains in perpetual fear of being killed, but in the end it is the deadly chemical cloud — the accidental release of poison gas by Union Carbide in December 1984 was the world’s worst industrial disaster to date — that takes his life. There is no escape for him, just as there isn’t for anyone in this novel.

The section set in the aftermath of the so-called Sepoy Mutiny, “The Line of Faith: 1859,” when the British came perilously close to losing India, involves a British military detachment pursuing a mutineer named Magadh Rai in the Himalayan mountains. The prose in this oldest of the historical episodes is the most elusive in the novel, evoking Flann O’Brien’s quirkiness in At Swim-Two-Birds. The element of pursuing while being pursued remains a constant, conjuring a disorienting fantasy of the psychological tortures that some of the characters who appointed themselves masters of the Indian realm might have suffered.

“Paranoir: 1947,” perhaps the most fascinating section, is about Das, a Calcutta veterinarian-in-training who shoots a horse that has just thrown off and possibly killed its British trainer, Walker, around the time of Indian independence. Colonialism has ended in a way that promises more rupture and dissension, as Das observes the likely fate of minorities and the new emphasis on particularistic identities, although he tries to save himself by believing that he is serving a do-gooder named Miss Srinivasan, and that a hidden entity called “the Committee” has assigned him to take charge of the Vimana, the superweapon promised in the Vedic scriptures. Depicting such nationalist delusion amid the exuberance that accompanied independence enables Deb to probe the shattered psyche of postcolonials taking control of their own history for the first time in centuries, but is also a commentary on today’s collective fantasies.

All three historical episodes can be interpreted as glosses on what Bibi might have reported. We can read Bibi as the novel’s very loose connecting thread — appearing with her own name in a historical episode she is said to have looked into — or more reasonably, as an afterthought, a personification of an India that cannot possibly care about any ideas, secular or socialist or even capitalist, and that has unraveled into a republic of chaos and darkness.

In the final section, when Bibi at last summons the courage to connect the dots and ends up locating Sanjit in the Andaman Islands — something of an internal colony within once colonized India — we are back to contemporary reality. Superficial comparisons might arise with such novels as David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, but Deb’s novel is more about the failure of modernity than anything else. In the veterinarian Das’s words:

He had left behind village life to become modern man, turning away from the contained, miniature world of his illiterate father and mother. Dark interiors, open vistas of farmland and water, rules and rites and festivals, two or three pieces of cloth to be worn interchangeably, a brood of siblings growing behind and around him. But modern man turned out to be about extermination, while the peasants he left behind came into the city to die in their millions. Those that remained alive were channeled by their modern brethren to attack and pillage and rape.

Das’s musings capture Bibi’s ultimately disappointing migration to the metropolis in search of a similar immersion in modernity, but also presumably the author’s ambiguity about his own self-modernizing project, which has taken him from the path of a provincial moving to the capital to report on Indian corruption and learning to decode the convolutions of Indian bureaucracy and management to his current role as an outsider novelist established in New York City and reporting on himself in the guise of reporting on India in the age of hyper-nationalism. As he tells us in the introduction to The Beautiful and the Damned, his 2011 nonfiction book on India, he was a journalist in New Delhi in the 1990s and lived in the Munirka district — which, as we have seen, figures prominently in the opening section of Light. Another example is his own investigation of the Union Carbide/Bhopal disaster in the 2000s, the subject of “Claustropolis: 1984” in this novel. The unusual length of time that has passed between novels, Deb’s eschewal of a sympathetic participant-observer role in favor of adopting that of an outsider who is a relentless critic, and the mining of his own early life after a substantial lapse of time are consistent with Light’s insistence on a peculiar density of prose that is rare in Indian fiction.

More than anything else, Light is a chronicle of the 21st century intellectual defeated by the forces of modernity, which have been twisted beyond recognition by a capitalism that has shut off all avenues of escape. Bibi, Sanjit, S.S., Das, and other characters are all manifestations of the same stultified capitalism once given to telling satisfying stories about growth and development, and now mired in pure surface and elusiveness. In The Light at the End of the World, Deb has constructed a monumental prose effort, but one that, in its fatalism, robs humans of their ability to effect change. All that the writer can do, to quote Bibi’s perception of the futility she sees around herself, is to chronicle “[t]he ruins of the Third World,” which was a ruin to begin with, and sever the past from the future. To read this book is not for the faint of heart.