Sheana Ochoa

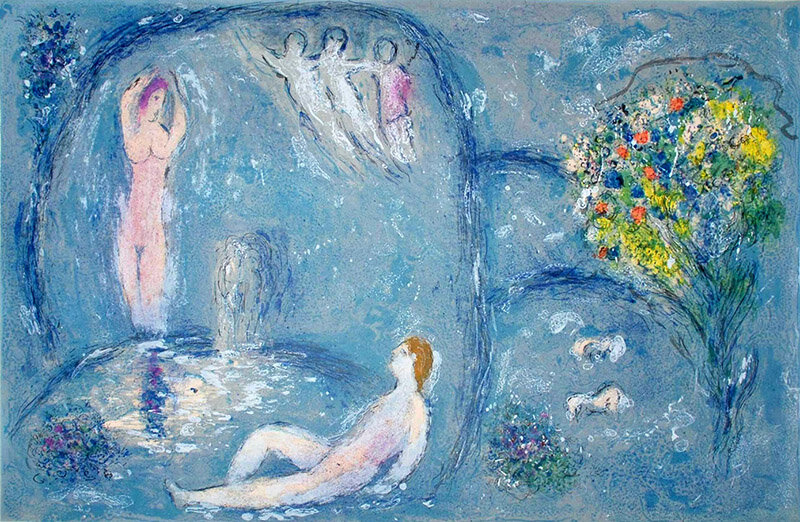

I met Adam at my regular meeting of Alcoholics Anonymous in West Los Angeles. That morning I had taken my usual route from the La Cienega onramp to Pico Boulevard and turned west toward the Pacific. The jacarandas were in bloom. Their dark branches all but disappeared behind ponds of periwinkle. From the mesa that is the 10 freeway, they sprawled across the city like an Impressionist painting — entire jacaranda-lined streets of pastel purple ablur. I turned down a side street to find the cars parked beneath the trees covered with the tubular shaped flowers — the asphalt itself a blanket of blossoms. As I drove, I could hear the pop pop pop of the flowers expiring beneath my tires like bubble wrap. I felt as if I had desecrated spring itself.

I arrived at the Unurban Café and found a seat in the windowless back room, part theatre, part gallery. Plastic flowers hung in vines from the ceiling in pink and yellow, their rubbery green leaves gleaming in the feeble light — the management rotated local artists’ work on the walls with no apparent schedule. I would show up once a week after getting my son off to daycare. I rarely stayed to socialize after the meeting. I just needed the weekly dose of recovery I found in a room of ex-drunks.

A wiry, elderly man sat amidst the rows of threadbare theatre seats across from me. He wore a black yarmulke, which was an unusual sight even in the motley rooms of Los Angeles AA. When the meeting opened for sharing, he raised his hand and said his name was Adam.

My introduction to and subsequent fixation on Jews began when I was five years old. Sundays we returned from church with an elbow-deep pot of menudo boiling on the stove, oregano and onion wafting through the house. After breakfast, my dad would sit in his overstuffed chair and open one of his secondhand hardbacks. One Sunday I climbed onto his lap, trying not to interrupt his reading. He licked his thumb to turn the page, and I saw the images for the first time: skeletal people with large, imploring eyes. Oversized, striped costumes draped from their bodies. My dad explained who they were, which I couldn’t entirely square with my limited scope of the world. I would return to the black and white photos in my mind. Soon they became a memory of terror and helplessness, and at some point — around the age of seven when my mother let my alcoholic father take me away to live with him, when Sunday church and menudo transformed into an itinerant life of home and food insecurity and I had no context for my feelings of abandonment — I would think of the Jews in the Holocaust. A sense of responsibility to save my brokenhearted father somehow conflated with the people in the photographs, who I thought were still waiting somewhere for me to rescue them.

In junior high I read The Diary of Anne Frank. I marvelled at Anne’s capacity to ignite the imagination through books and writing, and express the stirrings of first love amidst the threat of annihilation. Her capacious zest for life transfigured the Secret Annex, her hideaway from the SS, into a wonderland. I wanted to learn how to use the alchemy of language to transform worlds, to transmute trauma. It wouldn’t come as a surprise when I later learned that my first name — chosen by my mom who had a coworker named Shayna — was of Yiddish origin, Yiddish itself a composite language spoken by Eastern European Jews. It made me feel chosen when I realized that I would become a writer, like Anne.

Soon after noticing Adam at my AA meeting, I spotted him on the street in my neighborhood, shoeless, standing outside the Pico-Robertson Jewish Community Center. I circled the block, looking for a parking place. I felt compelled to stop and talk to him, not that I was consciously making any decisions; it was more visceral and instinctive, like lunging for a falling object.

Adam was carrying a box of new white shoes the community center had given him. Two plastic grocery bags hung loosely from his wrist. His thinning gray hair and scraggly beard outlined a drawn, chiseled face. His eyes matched the electric blue sky swept clean by the Santa Ana winds. I approached his diminutive frame, realizing he had no idea who I was, nor cared. I’d never actually talked to him before or noticed what was evident outside the community center where we were standing: Adam was living on the street. He sat on the sidewalk to try on his new shoes.

—Hey, Adam. I’m Sheana. I see you at the meetings.

“As soon as I entered the bathroom, I realized my mistake. I assumed Adam had closed the bathtub’s sliding glass partition, but it was wide open, his ropy body submerged under the suds. Puddles reflected off the white tile floor like a jury of mirrors.”

He rose in his socked feet. —Sheana, he repeated, recognizing the word as much as the name, the reaction most Ashkenazi Jews have when they hear my name. Usually they ask if I know what it means. They incant shayna punim or shayna maidel and silently recall their bubbe, or their first sweetheart: pretty.

—Do you want a sandwich? There’s a deli next door.

He nodded and walked with me toward the Persian kosher deli.

—These shoes hurt, Adam announced plainly, which is when I suggested he sit at an outside table while I ordered. As soon as he sat down the deli owner ran out of the store, yelling at Adam to leave.

—I’m buying food! I yelled back indignantly.

—This has nothing to do with you, the owner said. —He comes in here and runs my customers away, shouting and cursing. He can’t stay!

I packed Adam into my front seat with his shoebox and plastic bags, heading for home where I could feed him and find him a shelter. He smelled of days’ old sweat and beer. He looked at me askance, smiling at his good fortune.

At home, Adam shuffled behind me, walking gingerly in his tight, new shoes. Then he sat down to remove them. His once white socks were gray as ash, but intact. I glanced as he peeled off a sock. His foot swelled with festering sores. They needed a good soak.

—I’m going to run a bath so you can soak those feet, I said, darting into the bathroom where I turned on the water, squeezed the bath gel into the stream to create suds, and then to the linen closet for a towel. It was all muscle memory. I’d been doing this for my son for almost three years. Run bath, make bubbles, get towel. I felt confident, capable, and that Adam understood he was in my care. Adam stood in the hall looking at my guitar sitting on the couch. I dug out an old pair of sweats and a tee-shirt from the bottom of a drawer and placed them atop the toilet tank.

—Go ahead, I said, gesturing him into the bathroom and shut the door behind him.

After making several calls, I learned the shelters were full for the day and one had to arrive first thing in the morning to get a bed. In Alcoholics Anonymous it’s not uncommon to let a member stay on the couch for a night or two, but I wasn’t comfortable with that in this case. I had taken out bread and meat for sandwiches when I remembered I had ibuprofen in my purse. It would help with the inflammation in his feet. I tapped on the bathroom door not thinking about the reality of a naked stranger. In my mind, his immediate needs took precedence over any notion of privacy. My concerns were practical: food, medicine, shelter. As soon as I entered the bathroom, I realized my mistake. I assumed Adam had closed the bathtub’s sliding glass partition, but it was wide open, his ropy body submerged under the suds. Puddles reflected off the white tile floor like a jury of mirrors. I handed him a pill with a glass of water and stood there so he could return the glass. When our eyes met, Adam looked coy, which I mistook for gratitude.

I heard Adam emerge from the tub as I made sandwiches, staring out past the wooden deck through the kitchen window. Below I could see the lemons, the ones I couldn’t reach, mocking me brightly atop the yard’s lone tree. The backyard butted against a row of detached tenant garages. They led out to the alleyway. Coming home, I would drive through the alley directly into my garage and enter my apartment through the backyard. I didn’t know how single parents who only had street parking managed. Did they leave the kids in the car while they unloaded the groceries or unpack the car after taking the kids inside? Sometimes Noah fell asleep on the drive home and I’d leave him in his baby seat until I put the groceries away. I had lived in Los Angeles almost twenty years and felt safe, but it was different now with a kid. I needed my garage. Adam cleared his throat, pulling me from my thoughts.

—Are you hungry? I asked him as he entered the kitchen. He didn’t answer, but when he saw me carrying our plates out to the deck, he grabbed one of his plastic bags. A gentle breeze blew the sheets on the clothesline. An ice cream truck ambled down the street. Adam barely nibbled at his sandwich. Sitting there I could see his clean, raw feet close up. They were a mess. No wonder he couldn’t wear shoes. I found my white terrycloth slip-ons — topped with pink bows — and offered them to him. They fit fine.

—There are no available beds at the shelters, I said.

—You’ll never see me in one of those places, Adam scowled. —I’d rather live on the street.

A burning sensation rose to my shoulders as I realized he wasn’t interested in what was on offer downtown, that my phone calls had been in vain. He shook his head as if disgusted with my suggestion of a shelter. From his bag he removed his Torah as well as an empty forty-ounce beer bottle and some tangerines. He placed these items next to his sandwich and offered me a tangerine. I peeled it. The skin came off entirely in one piece. Dried, white molt encased the colorless fruit beneath.

After lunch I moved my car out to the street so Adam could spend the night in my garage. The sideboards and rafters, redolent of an old country barn, would almost be homey if the place had windows and you put in a clean floor. The late afternoon sun shone through cracks in the wood. I brought down a sleeping bag and some candles. Adam pulled my cooler from a corner of the garage to use as a table. He spread out the sleeping bag next to the cooler. When he seemed settled, I turned to go, feeling relieved he didn’t expect me to entertain him.

—I have work to do, I said, but I’ll bring some dinner later.

—And your guitar, he queried, revealing yellow, rotting teeth as he smiled for the first time. The smile shattered an unacknowledged impression I had of him. It said, “I know what I’m doing.”

—It has a broken string, I said.

—I can still play it, he assured me.

Later that afternoon I picked my son up from daycare. We went out for Mexican. I ordered a burrito for Adam. The sunset poured from the horizon like a violet Rorschach and bled into the thinning clouds.

—Noah, look at the sky!

—It’s purple like the jacaranda, Mommy.

He pronounced the “j” like an “h” the way I taught him, the way you say it in Spanish.

At home I put in a Baby Einstein video while I ran down to the garage. Adam had the garage door open so he could see by moonlight, but I didn’t feel safe having the backyard accessible to the alley.

—Don’t keep that open, I said, handing him the burrito.

Back upstairs Noah asked, —Where did you go, Mommy?

—I was just checking on the garage, I said.

I scrubbed the ring of grime from the tub with Comet before running Noah’s bath. Later that night, after I put Noah to bed, I found Adam reading from his Torah by candlelight. He had taken down several things I kept stored in the rafters. In the flickering light an artificial Christmas tree stood lopsided on the cement floor. A five-gallon paint bucket made a good chair. Old artwork I hadn’t gotten around to throwing out lined a wall. A close-up photograph of a ballerina on tiptoe, her light salmon slippers antiquated from use. A tapestry of flamenco dancers my father had glued onto plywood and given me.

I handed Adam my guitar and asked if there was anything else he needed. He answered by asking if my son got to bed all right. It was innocent, but I didn’t want Noah involved in any capacity with Adam. He needed to be protected from the trauma I had never named or dealt with, the conflation between the aftermath of my parents’ divorce and the collective horror of the Holocaust. The end of my childhood dovetailed between these two realities along with an overwhelming sense of being somehow at fault.

When Adam opened his book, I saw that it was in Hebrew. He said he had gone to rabbinical school. I thought, I’m practically harboring a rabbi in my garage.

—You’re interested in learning Hebrew? he asked.

I nodded. I had often thought about what it would be like to convert to Judaism, but it was one of those half-hearted desires trumped by the more immediate ones of finishing my first book and raising a kid I’d elected to have as a single mother, the sole parent responsible for keeping the family and my son’s childhood intact.

—I could give you lessons for the garage.

I didn’t know what to say. The idea of Adam living in my garage took up enough room in my head to be dismissed the way you’d sentimentally want to adopt a street kid on your travels until you thought it through. I mentioned the shelter again. He said he had stayed in shelters and he was not going back. That’s when I realized I had to take him to the AA meeting in the morning and leave him there. I leaned over to try to straighten the Christmas tree, but its base was damaged. The nerve of him, I thought, going through my things without asking.

Adam picked up my guitar and strummed a familiar melody.

—There’s something else I’d like, he said, coming back to my question. A radio. I brought one down, and then sat at the edge of the sleeping bag. Adam tuned the radio to a jazz station.

The moon was on the rise. The fluttering candlelight cast pointed shadows along the disjointed sideboards. I didn’t ask if he had family and he didn’t ask if my son had a father. We could have been anyone anywhere. Miners on break. A boy and girl discovering an abandoned shack. Travelers seeking shelter. Mahalia Jackson’s “Come Sunday” animated the walls with something like breath. We listened together, two parishioners at Sunday church, our wooden chapel expanding and collapsing with hearty, gospel verse.

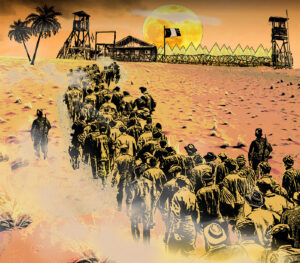

Over half a century after Anne Frank was killed in Auschwitz, I traveled there by train. I was nineteen. The town of Birkenau is less than two miles away from the camp. I was appalled by a community of orange tiled-roof houses dotting the road. It felt unholy to have a home in sight of the camp. How does one say I live in Birkenau? I imagine it’s no different nowadays than when it was a killing factory: by immunity. The site becomes as banal, as quotidian as the local grocery. When you live amidst something day in and day out, it becomes invisible, and yet everything that exists eventually becomes embodied.

I walk through the entrance to the camp. Steel cut lettering spells out Arbeit Macht Frei in capitals overhead, but I am not transported. My field of vision extends a mere three feet in front of my face as if I am wearing side-blinders. This keeps me from integrating my senses in any cohesive way. My mind folds in on itself, leaving an inextricable numbness of presence. I have no map, no tour guide. I aimlessly enter a building where I pass the windowed rooms with mounds of shoes, prosthetics, spectacles and valises. I look for something that hasn’t already been interpreted for me by photographers, filmmakers and historians. Something that I have to reckon with by myself.

I follow the train tracks to the arrival platform at Birkenau, or Auschwitz II. It’s so familiar it feels cliché. I walk into the barracks and look down one of the cement holes of the communal latrines. I imagine hiding below there in the shit-sludge. I know this too is not an original thought; it is a scene in a story I’ve read or a film I’ve seen. I return to Auschwitz I, where I wander around the yard. I can’t seem to connect the dots. I look up. I am standing beneath a wooden structure built for public hangings, directly where a body, many bodies, had been hanged. I remain where I am to see if I can feel anything. There could be a haunting. Or am I trying too hard? I step away because I can’t bear to take up that space on the planet. I have not returned to my body, not because I have been placed at the scene of the crime, but because the crime is too immense to inhabit.

I walk into Cell Block Eleven, still without a sense of grounding or narrative by which to stitch the experience. And then in a narrow yard, between this and another brick building, there it is: the Death Wall. It stands storm-cloud gray and porous as if made of lava rock. The wall is at least eight feet tall and shaped like a proscenium arch, the better to contain the prisoners executed by gunfire against it. Blinders off, I play out the scene: men and women are made to undress in Cell Block Eleven. They queue up to be marched before the wall, which absorbs each day’s pistol-slung blood. I don’t want the reality in front of me. I want a Secret Annex of discovery, romance, and hope.

I touch the dry pumice. The contact of flesh and stone transports me elsewhere. A trick of the mind. What I learned from Anne Frank. It serves to protect. And so, I envision not a wall, but a partition. Yes, a bathing partition of the Art Nouveau tradition you find in bathhouses in Budapest. The partition separates the men’s from the women’s baths, its surface covered in gold-specked cerulean blue tiles. You can smell the loamy healing waters. And the brick building that in some alternate universe is referred to as Cell Block Eleven transforms into a changing room for the bath’s patrons. They undress leisurely from their constricting street clothes into swimwear. They enter the courtyard wearing candy-striped, high-waisted suits and rubber swimming caps. Two girls are giggling. A grande dame snaps open her parasol, sparking an irreverent whistle from the lips of a young man in belted trunks, leaning against the bathing partition. With a dismissive flutter of her eyelashes she forges a detour away from the River Styx.

The morning after Adam’s stay in my garage, he was blaring the radio — Beethoven’s Ninth. I hurried to get my son ready for daycare. We hustled out the front of the apartment and down the stairs to my car. I drove around to the alley to find the garage door open again, and Adam performing his ablutions from the paint bucket he had filled with water.

—Mommy, who is that? My son’s eyes widened at the man in our garage.

—Just a minute, mijo. I’ll be right back, I said, parking against my neighbor’s garage door.

—It’s too loud, I told Adam as I walked over to the radio and turned it off. —I’ll be back in five minutes and we’ll go to the meeting.

Realizing my son was in the backseat of the car, Adam walked up to the window, waving hello. My son scanned the gangly figure and looked back at me. Adam told me he didn’t want to go to a meeting. I drove off, weighing my options.

—Mommy, why did that man have your slippers on?

At the meeting I explained that I needed to get Adam out of my garage. My friend Bill offered to help. When we got back to my apartment, we found Adam on my deck drinking a bottle of beer, his feet propped up, playing my guitar.

—Hey Adam, I hear you don’t want to stay at a shelter? Bill said.

—Who are you?

—You know me, Bill, from the meeting. Hey guy, you can’t stay here. Someone lives here.

—I know that! Adam snapped, rising. He looked at me, confused. He sat back down and picked up the guitar. —If Sheana has something to tell me she can say it herself.

—You can’t stay in my garage, Adam, I said, recalling how Adam had tried to barter Hebrew lessons for the garage. Had I made it clear that that was not an option?

—You heard her. You don’t want to get her evicted.

Adam put down the guitar and headed toward me. Bill stepped between us.

—I want to talk to Sheana, Adam said.

—Get your things, Bill said, reaching for Adam’s plastic bags. Adam snatched them away. Bill tugged Adam’s shirt in an effort to remove him from the deck.

—Get your hands off me! Adam said, swatting at Bill.

I thought Bill was going to take a swing. —Please, Adam, can you just leave? I asked.

Adam froze, staring at me. —I will! I’ll leave now that you said something, Sheana! He started down the stairs. Bill followed him and saw him out through the alley.

Later that afternoon Adam was back at my front door as if paying me a visit. He handed me a clean plastic bag. Inside was a toddler-size hoodie for my son, striped yellow and brown. Guilt made me take it. Sentiment made me wash it and dress Noah in it the next day. I presumed it was some sort of parting gift. The day after, Adam was at my door again.

—Adam, I don’t feel comfortable with you hanging out around here.

—You shouldn’t have looked at me that way then, Sheana.

I raised my eyebrows.

—You know what I’m talking about, he continued. —I was naked in your bathtub and you stood there looking at me longingly. I saw a light in your eyes. You shouldn’t have smiled at me that way.

I flashed back to handing Adam the ibuprofen, being surprised that he hadn’t closed the glass partition.

After Adam left, I called the police. Two men in uniform showed up, telling me I should be more careful. That I can’t go around bringing people off the streets to my home.

—He will keep coming, the cop told me, —because you’re the most important person in his life right now.

Several days went by without word. I went to the AA meeting half expecting him to show up. Late one night, after my son was asleep, the doorbell rang. I looked through the peephole at Adam’s distorted face. I kept quiet.

—I thought we had a deal, he said through the door.

And we had, hadn’t we? Sitting by candlelight, listening to Mahalia Jackson. By giving him refuge, I was trying to create my own. Two refugees, that’s what we had been. It was as if by saving him I could alleviate the guilt I’d been carrying around since childhood, since first seeing the Holocaust pictures and thinking I could save them, since taking my mom’s place emotionally for my dad, for failing at both. Irrational, I know, but trauma is compounded this way, illogical and messy, leading you into a shadowland of shame. After several minutes standing there, I crept back to my bedroom like a child up after bedtime, trying not to get caught.

The next day I came home and found a white peony on my doorstep. When I picked it up half the petals fell off. Its filaments disintegrated as I carried it to the trash, tawny remnants falling on my hardwood floor. Later that night, he rang again. I didn’t go to the door this time. He left a bag of lemons on the stairs. I thought about calling the police again, but realized they couldn’t do anything. Eventually, he stopped coming.

A year later, I was leaving an AA meeting on Vine Street in Hollywood when I saw Adam again. He was standing outside, disheveled, rocking from one foot to the other on the curb. I finished exchanging numbers with a woman I had met, hoping the crowd wouldn’t thin out and leave me exposed. I heard a couple AAs say hello to Adam. The three of them walked up the street in the direction of where my car was parked. The trio parted at the intersection where Adam leaned against a waist-high concrete wall outlining a strip mall. This is silly, I thought. I can’t wait him out. I began walking toward my car. As I approached Adam, his eyes didn’t seem to register me or anything else. I took out my cell phone and pretended to be engrossed with it. I waited at the crosswalk, Adam now only a few feet behind me. He was unaware of me, faded as he was from the world of color. I got in my car and headed home.

The jacarandas were in bloom. I took Vine south and made my way onto June Street. Petals blanketed the curb-side cars, their windshields frosted in purple snow. An untouched carpet lay ahead of me along the asphalt and I could already hear the pop pop pop of their expiration beneath my tires. I pressed on the brakes and turned around. The flowers had fallen, but their tubular forms were still puffed out and present. I left them that way on the street. Their integrity still in tact.