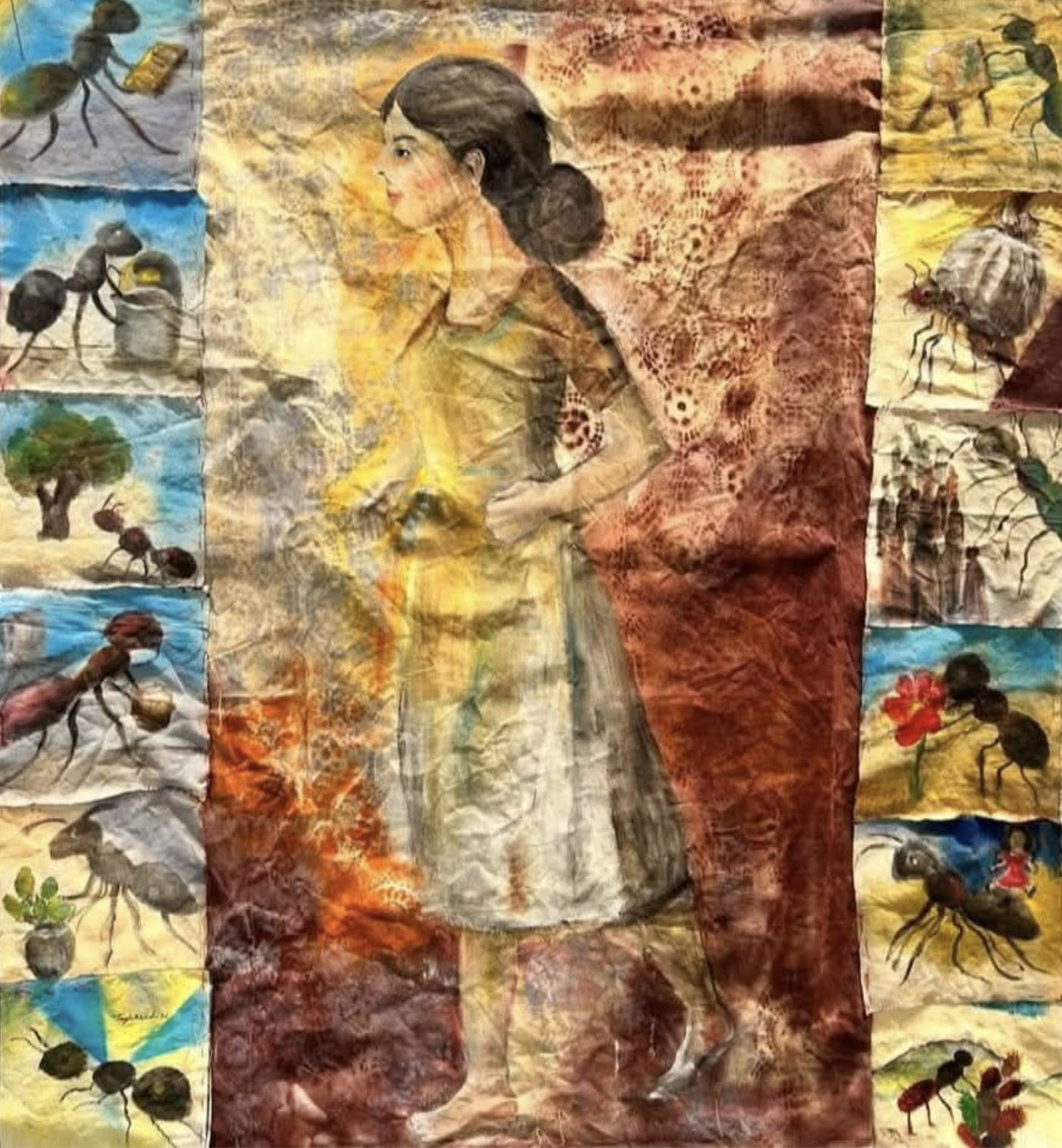

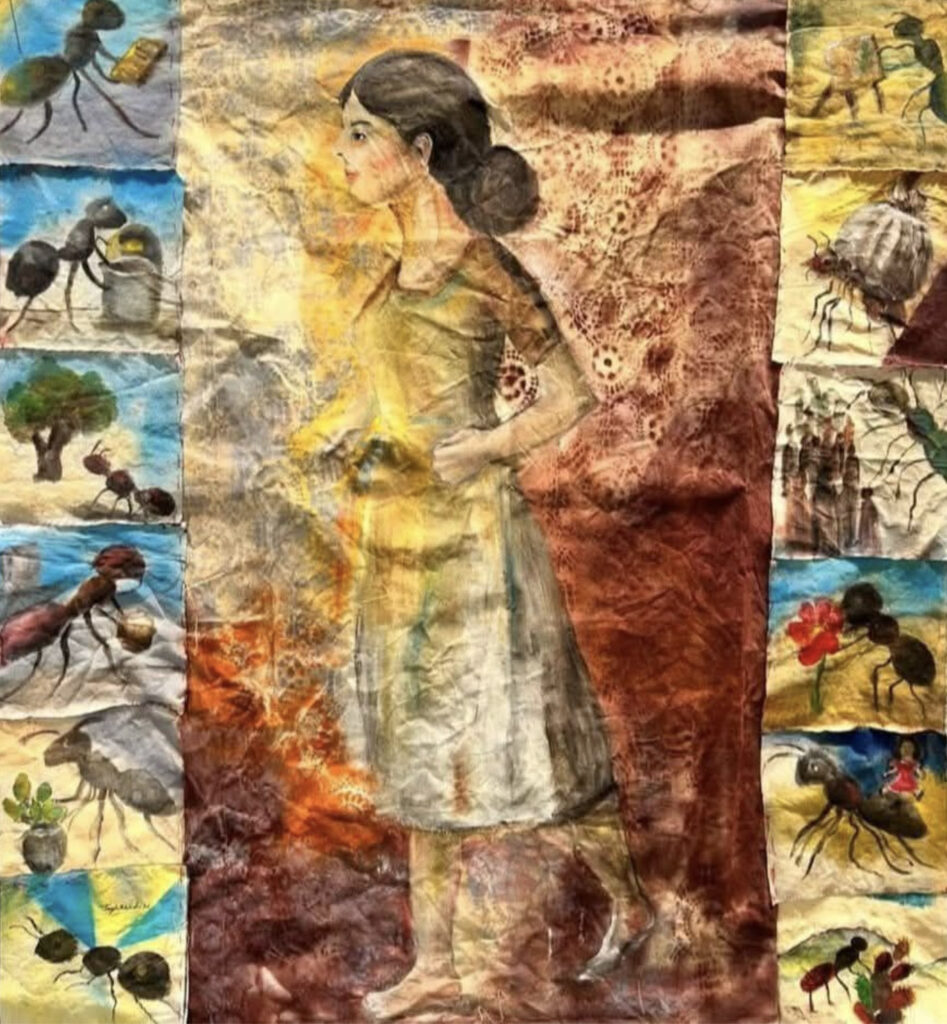

Neemah Ahamed explores what home means when one's life is upended and what once held cherished emotions disintegrates.

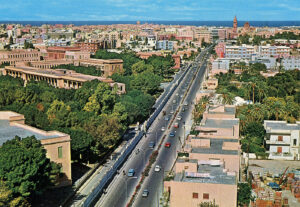

Growing up in Nairobi, as a third-generation Muslim Kenyan woman of Indian descent, I was accustomed to living amid political unrest, student riots, police violence, corruption, and burglaries. After a night out with friends, on the journey home, I would shift into a tightened, hyper vigilant state, checking my rearview mirror for headlights of a trailing car, fearful of being hijacked. At the same time, I needed to brace myself for the road ahead of me and look out for police roadblocks. Cast with shadows of uncertainty, the ride home was always restless.

In a podcast in October 2024, Adania Shibili describes how she experiences home “always as a state of restlessness.” The idea of home, she explains, “is not a question of safety. So it becomes somewhere else and something else.”

From my teenage years, home was a place where I was never quite still. I initially associated it with a space where I spent time with my mum, which never felt enough. When she was not helping my dad at work, she dedicated her hours to my sisters and me. She took on the task of saving me from myself. This included setting and marking math tests for me to sit on school nights so that I would not fail them abysmally the following day. When I saw her reach for her set of car keys, I would turn and ask her when she would be coming home. Ironically, that was the last question I murmured to her over the phone while she was in hospital, the night before her unexpected passing. That day, my restlessness was interwoven by the fear of abandonment and having to live without her. In her book, Recognizing the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative, Isabella Hamad refers to the late Javier Marías’ words. “I did not want to know but I have since come to know,” he wrote. “To recognize,” Hamad continues , “is something to perceive clearly what on some level you have known all along, but that perhaps you did not want to know.” Without understanding it at the time, confronting the truth about having to face life without my mother, was something I did not want to do.

In bell hooks’ essay, “Homeplace (a site of resistance),” the home embodies resistance, rejuvenation, and emotional and physical nourishment. It was a place where Black families could be recognized and feel safe within a wider nation that tried to erase their humanity. Does recognition mean being seen? And by whom? I spent the latter time of my teenage years and twenties looking after my father, who was shattered by my mother’s passing. The dynamic shaped by this loss was one where recognition was one-sided; because of his own emotional limitations, he lingered at the periphery of my internal world, unable to be fully present and stand in it with me, and I was never quite at ease. Not in the form of an epiphany, but in the way fractured pieces of memories get sewn together over time in one’s mind, I am learning that recognition is something that I unknowingly longed for as a daughter.

In 2013, not long after my dad departed, Westgate, a large shopping mall a few meters from my family home, was raided by four gunmen from the Islamist militant group, Al-Shabaab. What followed was a four-day siege in which shoppers were held hostage and killed. Survivors were trapped in storage rooms and under furniture, and barricaded in shops. At the time, I was living near Westgate with my husband and the gunshots and sound of the helicopters’ drone hovering over the mall casted a weight over our days. We both knew someone who had been in the mall and received calls from loved ones who had friends who had lost their lives in the unfathomable attack.

In its aftermath, while still in the midst of trying to make sense of the tragedy a few days later, I heard my neighbor Julie screaming. The scenes from newsreels of Westgate began to play in mind. I called my husband, who confirmed that he had received a disconcerting phone call from Julie saying that someone was trying to break into her flat. He told me to turn off the lights and lock myself in the bathroom. As I huddled in my pyjamas, under the sink, on the cold floor, I broke into a cold sweat. I could hear the gunshots outside. Beams of flashlights scoured the balcony. I wrestled with conflicting thoughts. I did not want to know but quickly understood that the robbers could break into my flat at any moment. Two hours later, against a barrage of gunshots, I heard the shootout between the robbers and the police, after which the noise subsided.

The following morning, I left the flat, and my marriage ended. I stayed with my sister’s family in a different neighborhood for a few days and then moved back to my family home. It made me alert in ways I never had been. I kept my mobile phone under my pillow at night before I slept and felt unease with the familiar murmurs of the old fridge that kept my home breathing at night. My home was filled with remnants of my parents. Without their presence, the frayed scaffolding of emotional safety was dismantled. Within a few months I moved to London and have made different places my home. As someone who is hesitant about change, I grapple with my resistance to relocation, and I continue to sit with this restlessness.

Despite the lingering fear that surfaces at the thought of being in Nairobi, I visit my sister and niece in the city once a year. On my most recent trip, as I was boarding my flight, I received a message from a friend. It said, “Promise me a thing, start thinking of how Nairobi can be your place again.”

Shortly thereafter, I sat in my sister’s garden letting the sunlight fall on me after a heavy downpour, trying to find a tangible way to connect to a place that used to be home for me. Can I feel a sense of connection because of the way the rain sounds when it falls? Or through the awakening smell of the fresh wet earth? Or how I am always surprised by the shade of blue sky? And since then, I have been waiting for a “recognizable” truth to emerge in relation to what home is for me now.

Deepa Bashtri, who translated Banu Mushtaq’s collection of short stories, Heart Lamp, said in a recent interview, “when one has another language, one has another way to be in the world. Goodness knows that women need their own rooms in the world.”

In the same way, one’s sense of being in the world changes if there is a space to call home other than the place where one grew up. I have been living in London for twelve years. Initially, wrestling with the phobia of having a break-in at night, during the day, I gave myself permission to step into the freedom London offered. I found my way around the city through swing dance classes. Dancing in flapper dresses, the music gave me the opportunity to step into a world different to the one I grew up in and provided me temporary respite from my restlessness.

Athens

Three years ago, however, after visiting a friend in Athens, I began to feel less enamored by London. I realized that I longed to visit Athens at every opportunity. I was charmed by it because it reminded me of threads that pull me to Nairobi. I found safety in the warmth of the people. The taste of the chilli prawns laced with lemon on the beach in Naxos reminded me of childhood holidays at the coast in Mombasa. What lingered in the aftertaste was the disquiet feeling of knowing the temporal state of resonance and that it would be overshadowed by restlessness when I returned to London. The last time I left Athens, my suitcase was filled with foods whose flavors stir parts of myself which I recognize and have been revived.

On weekends, I make Greek coffee in a briki, a narrow copper pot which allows the coffee to foam up slowly. I eat Greek chocolate tahini on toast. I buy Tsoureki from local Greek restaurant. The closest bread I can describe it to, but, not quite, is brioche. When I first asked for it, the owner of the restaurant asked me where I was from. I felt he was trying to place whether it was my Greek roots that brought me to a place that did not have this bread on their menu but that those same roots also drove me to believe that there may be a secret stash tucked away for Greek customers. (I have now been accepted as an “insider” for these purposes). My favorite chocolate is choco freta, made of wafer, that reminds my Athenian friends of their childhood.

I don’t speak or understand Greek, aside from a few words like signómi, polý oréa — hello and thank you. I listen to the music of Antonis Remos and Nikos Makropoulos. Their voices imbue a sense of longing and heartache. I began to listen to these artists when a friend staying with me was going through a breakup. She eventually recovered, but their music continued to have resonance. Although I cannot understand their words, they are emotionally legible. They carry the undertones of unspoken and unhealed abandonment, quiet grief, and the murmur of longing to be seen.

These are echoes from my past that follow me. And in the textured sound of the melody, tone, and voice, my restlessness is temporarily steadied. It gives me the comfort of feeling the presence of a close friend. The music serves as a gateway to becoming. It enables me to recognize something that I always knew but did not want to know — that closeness is different from presence.

In the way that Athens holds pieces of me, a few days ago, that same friend who asked me to find a connection to Nairobi, sent me a photo from her apartment in Paris, her sanctuary, from where she lives in Luxembourg. The accompanying note read, “I am home again.” In that week, I also received a text message from my former supervisor. She had just come back from a week in Cuba. Her message said, “My heart is still in Havana.” In both cases, being in another physical place kindled something within them. Maybe the awakening of this feeling is a step towards homecoming.

What is home when you feel upended and where what has held you emotionally frays and starts to dismantle? For the last month I have been volunteering at Palestine House, a cultural community hub in London, that brings together and holds meaning for people who want to think, create, read, share, and reflect on Gaza. Architecturally, it follows the design of a traditional Palestinian home, with its arched doorways, high ceilings, and tiles. The bricks and stones used to create the space have been brought from Palestine. The large keys hanging from the ceiling are a tangible reminder of the homes lost during the Nakba.

A few months ago, an exhibition named Memories Carried created by the Iraqi photographer, Yamam Nabeel, featuring the plight of the individuals displaced in 1948, was strung across the space. The keys and photos symbolized restlessness, displacement, longing, and loss. They stood in juxtaposition to the space which had been transformed into a Palestinian village in which the owner of Palestine House welcomed his customers, like guests at a wedding. Unlike a celebration, the mood was tinged with sorrow and restrained warmth. This once again made me interrogate what home means to me. Palestine House bears witness to truth and recognition; to restlessness and to grief; to fractured belonging and to displacement; to pain and resilience; and to the quiet longing to be seen and feel presence. I have come to understand that it is because it offers and mirrors these truths that I am drawn to and return to it. It enables me to continue to strip bare what the meaning of home is as it stands for me in its frayed, dismantled scaffolding.

Maybe the paradox is to recognize that home for me is not a place, but a state of “restlessness.”