M.F. Husain, one of India's most prolific — and polemical — artists spent his later years in self-imposed exile in Qatar.

DOHA — M.F. Husain’s Qatari passport sits in a display case near the entrance of Lawh Wa Qalam, the museum that opened November 28 in Education City, and the first in the world dedicated to his work. The museum was built under patronage of the state that gave him citizenship when his own country forced him into exile. Ironically, one of India’s most famous modern painters died outside India — Husain died a citizen of Qatar.

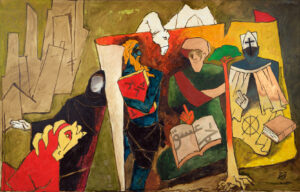

M.F. Husain (1915-2011) was one of few artists in South Asia to work at such a scale or draw such sustained reaction. He arrived in Bombay with little formal training and earned money painting cinema hoardings, massive film posters on wooden boards. In 1947, Francis Newton Souza brought him into the Progressive Artists’ Group, the collective that helped define Indian modernism after independence. By the 1970s, he was a household name.

I remain an Indian painter whether I am painting in Paris, London, New York, or Qatar.

He painted constantly, prolifically. On canvas, on wood, on paper, in series. He worked in public, finishing sketches in restaurants and hotel lobbies. The total output includes original paintings, cinema posters, prints, serigraphs, lithographs, drawings. “Across India there are more than 30,000-40,000 of my works,” he told NDTV late in life. “That is the most important thing I have given to my beloved country.”

Then the paintings became legal cases.

In 1996, rightwing Hindu groups vandalized Husain’s work in Ahmedabad due to a 1976 painting of the goddess Saraswati depicted nude. Two years later, his house in Mumbai was attacked over his depiction of Hanuman carrying an unclothed Sita. The complaints multiplied. He had painted an unclothed figure mapped onto Bharat Mata, Mother India herself. Prosecutors filed criminal cases across multiple Indian states. Each carried potential jail time; each required Husain’s physical presence in court.

The legal pressure accumulated over a decade. By 2006, Husain was in his nineties, facing summons from courts across India, traveling between Dubai and London. He stopped returning.

He refused the framing. “I am a free citizen; I haven’t committed any crime,” he said. “This is about a few people who have not understood the language of modern art. Art is always ahead of time. Tomorrow, they will understand it.”

Exile stopped being metaphorical. “Nothing is stopping me; I can return tomorrow,” he said publicly. But he didn’t return. He acknowledged new citizenship. “I am a Qatari now,” he said. But identity stayed fixed elsewhere. “I remain an Indian painter whether I am painting in Paris, London, New York or Qatar.”

He died in London in 2011, a Qatari.

•

Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, Chairperson of the Qatar Foundation, commissioned Husain to paint a series on Arab civilization during his final years. He completed over 35 works for this series before his death. She also commissioned “Seeroo Fi Al Ardh” (Journey on Earth), a kinetic installation he conceived in 2009 but never finished. The Qatar Foundation had it completed posthumously and unveiled the work in 2019, six years before opening this museum.

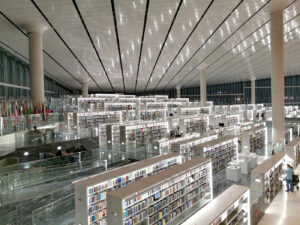

The Qatar Foundation, established in 1995, builds cultural institutions the way it builds universities. The foundation brought branches of Georgetown, Northwestern, and Carnegie Mellon to Education City. It operates museums, research institutes, arts programs. Sheikha Moza chairs the board.

Qatar opened its Museum of Islamic Art in 2008, designed by I.M. Pei. Mathaf, the Arab Museum of Modern Art, followed in 2010. The National Museum of Qatar, designed by Jean Nouvel, opened in 2019. The Husain museum is the latest. The pattern holds: acquire the artist, complete the work, build the museum, integrate it into the educational infrastructure.

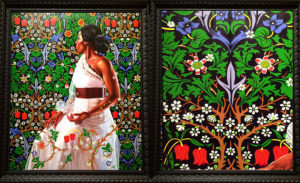

The Husain commission was personal and institutional at once. Sheikha Moza traveled with the artist to Yemen. She appears in one of his late paintings, a triptych on the Abrahamic religions, her robed figure anchoring the Islamic panel. The relationship produced work and eventually a building to house it.

From a cultural perspective, an artist’s existence is marked by a rare duality: one life is confined to the finite time they spend on earth, and another is lived as a creator whose vision endures through their legacy. In this sense, legendary artists do not experience a cultural death; rather, they continue to survive in the collective memory of humanity. This is the beauty of their craft; vivid in their presence, and eternal in their absence.

Maqbool Fida Husain was one such legendary artist — a true master whose artistic works transcend borders and connect cultures, histories, and identities. –HH Sheikha Moza

Critics who observed the late paintings had mixed reactions. Kishore Singh, writing for Business Standard, remembered a time when Husain was dismissed as “too gimmicky or too market-driven,” a judgment that resurfaced as the scope of his Arab civilization commissions became more prominent. These works present a question about the nature of patronage: does it liberate artists to work on their own terms, or does it redirect their focus to fulfill the desires of the patron? The paintings in Lawh Wa Qalam museum embody this tension, existing as both the product of Husain’s vision and the result of the Qatari cultural context that supported it.

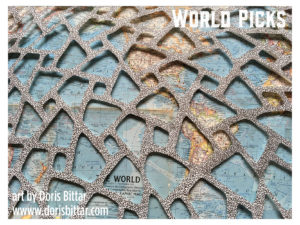

The building design for the Husain museum came from a 2008 sketch by the artist himself — “Lawḥ Wa Qalam” (Tablet and Pen) — which was executed by Delhi-based architect Martand Khosla after Husain’s death. The museum sits on a corner of Education City, its blue-tiled exterior catching late afternoon sun. Twenty feet away stands the cylindrical glass structure housing “Seeroo Fi Al Ardh.”

Khosla had met Husain, briefly, once at a family friend’s home in London when Khosla was studying architecture, and a second time at Husain’s studio, which happened to be in the same Mumbai building where Khosla’s parents lived. Husain wrote a letter about it that the university mounted at the entrance. The connections run through families, through chance meetings, through a small world of Indian artists and architects who knew each other across decades and cities.

Husain, Indian by birth, Yemeni by ancestry, Qatari by citizenship, fit the framework.

Another meeting came through his grandfather. “He had a studio briefly in an apartment two floors below where my parents had an apartment. So I met him there in the studio.” Years later, Khosla’s firm designed the M.F. Husain gallery at Jamia University. “He wrote a lovely letter, and they put it at the entrance to the gallery.

•

Working from Husain’s sketch meant interpreting rather than transcribing. According to Khosla, a blueprint in some sense is a very precise set of instructions, therefore the inference would be that the room for interpretation in the blueprint is limited. Whereas the room for interpretation within a sketch is much more. A sketch has inherently built into it; there is intent but also a certain tentativeness.

The sketch accounts for about a third of the building. “Two thirds of it is derived from language developed from the sketch,” Khosla told The Markaz Review. The blue tiles reference Central Asian architecture; the positioning responds to Doha’s climate and to the existing cylindrical structure.

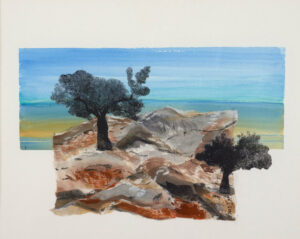

His thinking tracked regional rather than national lines. “If we look at sort of post-colonial divisions and national identities, that’s one way. I’m in South Asia. The museum is in West Asia. If I really go back some years, these are regions that have been connected for centuries. Influenced each other’s language, food, clothes. There are trade routes that started on the west coast of India and go to Yemen, trading all the way to Europe via Alexandria.”

“I would really hope the museum becomes more of a regional connector, a contemporary bridge between regions. I would really hope the museum plays a part in bringing together a greater Asian identity. South and West.”

The architect’s vision aligned with the patron’s. The Qatar Foundation’s cultural programming emphasizes cross-regional dialogue; Education City brings Western universities to the Gulf. The museum collection spans geographies. Husain, Indian by birth, Yemeni by ancestry, Qatari by citizenship, fit the framework.

The entrance opens through a golden arched doorway into a room anchored by personal objects. The passport sits in its case. Nearby, a photograph of Husain barefoot. Brushes. A palette. A kurta splattered with paint.

“When you walk into this first room,” Kholoud Al-Ali said during my visit, “it’s really like entering his home. He’s welcoming you with fragments of his life: the passport, the codes from his different disciplines.”

Al-Ali is Executive Director of Community Engagement and Programming at the Qatar Foundation. “It became a philosophy,” she said of the barefoot photograph. “Becoming a citizen near the end of his life meant something profound to him.”

“It’s better to let this room breathe for a few minutes. To let people feel who he was before we start explaining him.”

•

Noof Mohammed, the museum’s curator, designed the exhibition across three main galleries arranged thematically. “Whether following the story step by step or exploring freely, everyone can engage with his work as creativity intends. With openness and curiosity.”

The next gallery is immersive. Husain’s horses gallop across LED floors in looped animation. Petals drift. A dancer dissolves into brushstroke. “This is how we ease people into his visual language,” Al-Ali said. “You’re stepping inside the canvases.”

Early paintings appear alongside documentation of his years painting cinema hoardings. “He worked in so many mediums. Tapestry, photography, printmaking. He was truly a polymath.” One work, “Doll’s Wedding,” connects to his childhood. “Painting on doors, playing with dolls, absorbing the textures of Indian life.”

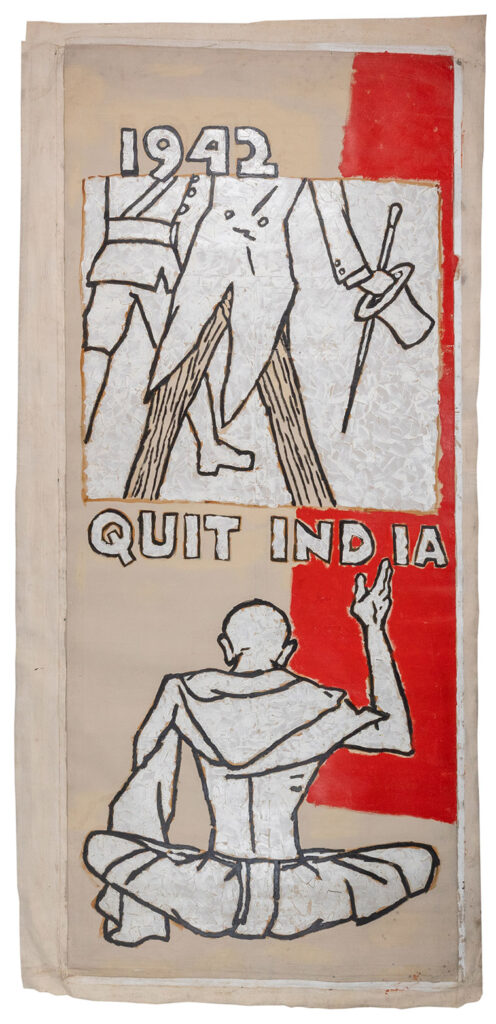

“Quit India Movement” (1985) takes up wall space in a later gallery. The painting centers on 1942, when Gandhi called for mass civil disobedience. Husain put the date at the top. Faceless colonial figures stride across the upper canvas in stark outline. Below them, a seated ascetic raises his hand. Gandhi’s image layers with the slogan “Quit India.” “He believed in Indian nationalism deeply, and yet later he was pushed out,” Al-Ali said. She gestured to Gandhi’s “Do or Die” painted beside Husain’s dates and life markers. “That contradiction sits inside this canvas. He didn’t leave by choice. He was forced into exile. So when you see this, it’s a conversation between personal history and national history.”

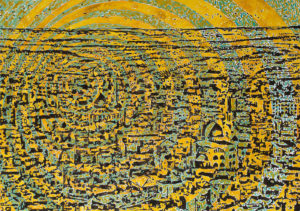

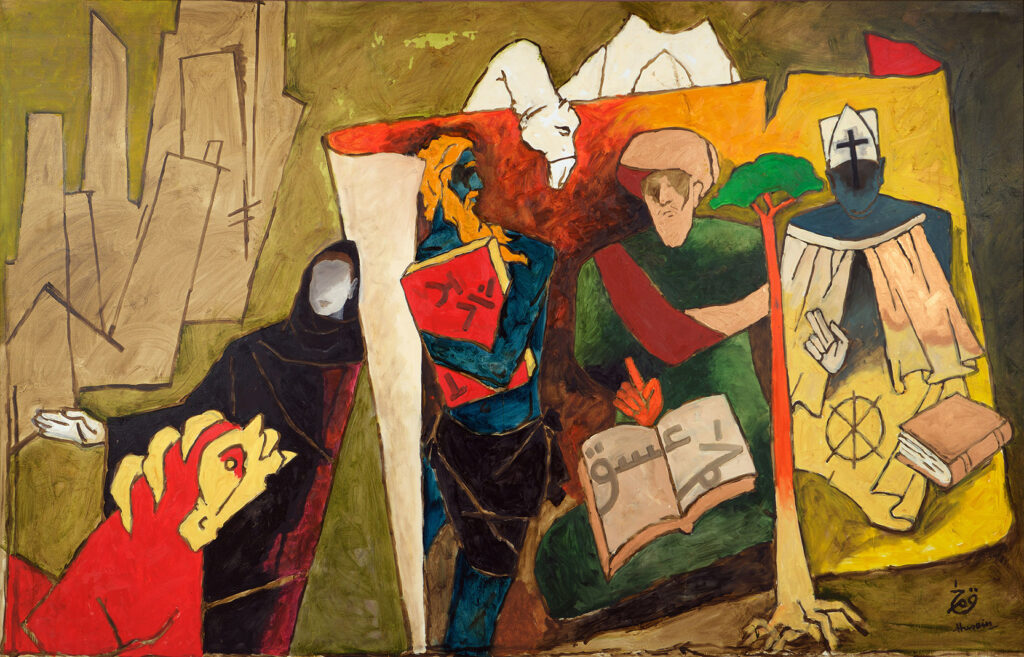

A later gallery shows interfaith work. “He believed deeply that different faiths speak to one another. That spirituality is a shared human pursuit, not a boundary,” said Jowaher Al Marri, Manager of Communications Outreach at the Qatar Foundation.

The triptych on the Abrahamic religions shows Sheikha Moza in the Islamic panel. “This work is about cross-cultural dialogue. Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Her Highness standing among them. Her posture is protective. She’s holding the space for the dialogue to happen.”

At the museum’s opening, Sheikha Moza cast Husain’s late work through the lens of dual belonging rather than displacement. “Though undeniably an Indian citizen, we recognize that he was equally an Arab Muslim: two identities that enriched his understanding of the human condition,” she said in her remarks. The framing emphasizes cultural bridge-building over the legal persecution that made his Qatari citizenship a necessity rather than a choice.

Faceless women appear throughout the religious works. “He lost his mother early in life. It became a visual language for grief and tenderness,” explains Al Marri.

Another work celebrates Barack Obama’s 2008 election by linking it to Bilal ibn Rabah, the first muezzin and a freed slave. “He saw a connection between these two moments. Both symbolized a new possibility for dignity and leadership,” Al Marri said. At 93, Husain stayed up through the night in Doha listening to Obama’s 2008 election victory; too elated to sleep, he began painting, connecting Obama with Bilal ibn Rabah.

The curator emphasized continuity over rupture. “I have always resisted presenting Husain’s Qatar years as simply an ending or something separate,” curator Noof Mohammed said. “Instead, I see them as the natural culmination of a lifetime spent searching, experimenting, and pushing boundaries.”

The final galleries show work from his Doha period. “Zuljanah Horse” (2007), “Battle of Badr” (2008), “Call of the Desert” (2010). Large canvases render motion through multiplication and blur. Calligraphy layers into landscape, Arabic script becoming visual texture rather than legible text. Husain’s Yemeni roots anchor the interpretation. “He traveled with Her Highness to Yemen, and those works show how naturally he blended Arab and South Asian cultural worlds,” Mohammed said.

The museum sits among the university branches. “The museum isn’t isolated,” Al-Ali said. “Students use it, researchers use it. Even engineering groups come to study the mechanical systems. Across Education City, we place art where people move. We don’t hide it. Art should challenge you, spark curiosity, disrupt your routine just enough to make you think differently. Art here is not decoration. It’s part of the educational experience.”

The Qatar Foundation’s model integrates cultural production with knowledge production. The museum functions as campus infrastructure. Students cross between the library and the galleries. Faculty assign visits. Artists in residence work alongside computer science labs.

“When we opened, it wasn’t only to honor a great artist,” Mohammed said. “It was to acknowledge the life he lived here, the work he left here, and how deeply he shaped people in Qatar. This museum is our way of sharing that tribute openly.”

The museum’s name, Lawh Wa Qalam — the Tablet and the Pen — references Surah 68 of the Quran. “It reflects the sacred roots of creativity in our tradition and mirrors Husain’s belief in art as a transformative force,” Mohammed said. “This title situates his work within a broader narrative of knowledge, imagination, and cultural exchange.”

The framing connects Husain’s Bollywood billboards to Islamic artistic tradition through his Yemeni ancestry and late religious work. Whether that connection holds depends on how you read the paintings themselves, and whether patronage shaped them or simply made them possible.

Among Husain’s thousands of works across India are original paintings, prints, lithographs, serigraphs, drawings, and reproductions.

M.F. Husain never returned to India. The museum is in Doha. The passport in the display case says Qatar.