Select Other Languages French.

Agri Ismaïl's novel is a tour de force that captures how modern cities transform immigrants into economic vectors.

Hyper, a novel by Agri Ismaïl

Coffee House Press 2026

ISBN 9781566897471

After a sweltering seven-hour drive through the West Virginia rainforest in my three-door Corolla, I finally reach the Swedish consulate in Washington, D.C. to renew my passport. The woman at the counter asks if I’ve lived anywhere for more than five years. I answer Abu Dhabi. She tells me that I must prove that I haven’t retained any other citizenships to avoid losing my Swedish one as my ties to the country are “weak.” She asks if I am a UAE citizen. I tell her that practically nobody is, not even those who were born there. She’s unconvinced and demands proof of my non-citizenship. I ask if such a document could even exist. She thinks I’m being a smartass and questions how she’d know if I were hiding an Emirati passport. I burst out laughing (which doesn’t help my case) and ask her to Google it. After deliberating with her colleagues for an eternity, she tells me that my passport can’t be processed at this time. I try pushing back, stating that my work visa would be violated, that I’ve never had an issue renewing my passport, that I love IKEA’s 75¢ veggie dogs, that I’d be forced to leave with nowhere to go (almost pithily announcing not wanting to succumb to the stateless Kurd trope). Dejected, I enter a nearby McDonald’s in a fugue state and pay $7.29 for one of the shittiest sandwiches I’ve ever had.1

Agri Ismaïl’s debut novel Hyper came at a time when I was convinced that such an experience couldn’t be captured on the page. For the uninitiated, the UAE is a revolving door of sorts, following the worryingly global trend of characterizing people as economic variables. It gatekeeps the (forbidding) requirements for citizenship, controlling people’s rights and their ability to mobilize, so that it can reserve the right to expel anyone who becomes even a minuscule burden on its boundless resources. This has been the prevailing Gulf narrative in stories and novels, and rightfully so.

But, as Hemingway would have wanted you to know, literature is not journalism. There is a universality in this experience, especially among those who come from volatile regions (which make up the vast majority of the population), that’s missing from the hit-piece headlines.

It’s an experience I and many others encounter time and again as we shift from continent to continent, sampling countries that ostensibly profess their pro-immigrant stance but treat us completely otherwise. Which is why I nearly deflated when I read that Noor Naga had given up after spending five years trying to write what would have been her first novel. Set in Dubai, she struggled to “find language to describe basic things” since it hadn’t been done before. 2 In sum, Agri Ismaïl’s accomplishment is nothing short of a literary miracle.

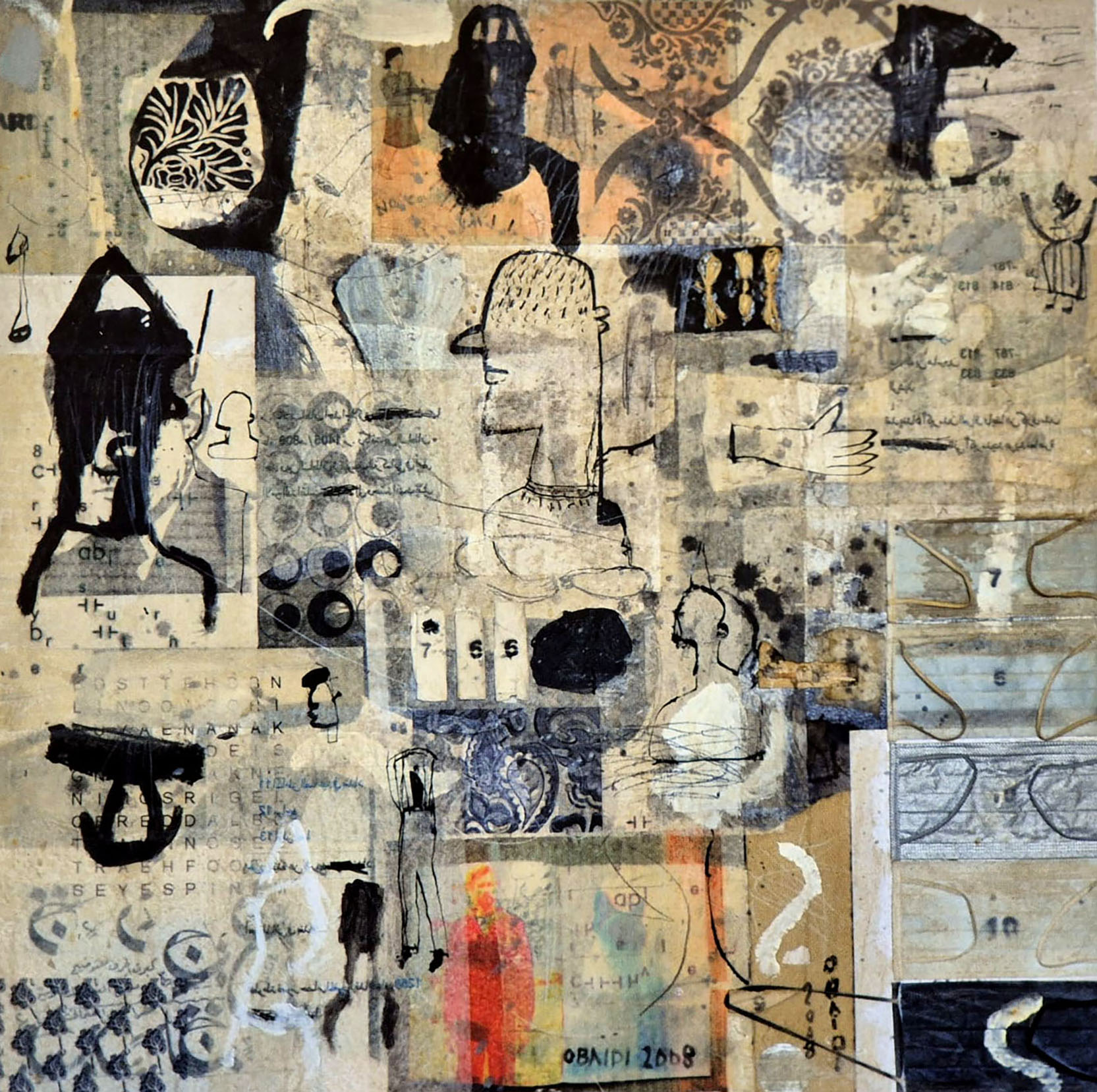

The kaleidoscopic novel follows three siblings — Siver, Mohammad, and Laika — chasing their fortunes in Dubai, London, and New York City after the 2008 financial crisis. We watch as their aspirations are progressively eroded in their respective cities until they’re spat out as an unrecognizable, formless mush. Their father (founder of the Communist Party of Kurdistan) Rafiq Hardi Kermanj, a depressed out-of-work physician who fell into poverty after fleeing his homeland, lives on welfare in England. The irony is almost too heavy, and yet the novel’s messaging is handled with such nuance and care that reducing it to any singular iconography would be an enormous disservice.

At its core, much of immigrant literature grapples with economic survivability, defining success and failure in terms of establishing a worthwhile career. Yes, money is at the forefront of all the protagonists’ identities and failures in Hyper (cripplingly so). But the novel cleverly deploys a dual assault on the reader’s expectations, lampooning both the common pitfalls of the melodramatic immigrant tragicomic autobiography and the indecipherable hypermodern footnote-ridden, non-linear multi-perspective doorstop. I wouldn’t blame anyone for digging up the famous photo of DFW, Zadie Smith, and Jonathan Franzen chatting at the 2006 Le Conversazioni to see whether Ismaïl was lurking in the background with a Hemingway Daiquiri and Moleskine.

Take the opening of Hyper, where we meet its (arguable) protagonist, Siver. We’re immediately drawn to her, as her husband (and eventually ex-husband) Karim casually announces his intention to take on a second wife, a teenager of 18 or 19 who works in his office. She laughs at first, assuming he’s joking, only to realize he’s serious. “She did not recall whether she actually entertained the notion of sharing her husband with another woman, but her leaving was not immediate,” Ismaïl writes. It’s one of the many strikingly insightful lines in the book, here neatly revealing the disconnect between Siver’s rational self and the emotions she has trouble accessing. In the flashback sequences that detail Siver’s first encounter with Karim while studying at SOAS, we learn of her reluctance to disclose her impoverished London suburb to her classmates, and her decision to identify as Iraqi rather than Kurdish.

Each moment shows her negotiating how to present her identity and reveals how Siver’s sense of otherness predates and persists throughout her (failed) assimilation in Dubai. This isn’t to say, however, that her crises aren’t exacerbated by the city. Far from it. We see Siver tackling her six-year-old daughter’s eye-watering annual school tuition of $20,000, swallowing her pride to ask her ex-husband for money in order to avoid subjecting her daughter “to any disadvantage due to her sodding pride.” As she grows more disillusioned with the city, an entropic meta-narrative subtly assumes control (à la The Yellow Wallpaper). Siver resorts to selling scarves that cost $24 to produce for $699 in the Mall of Emirates and has a series of encounters with men who flirt with her by announcing what they do for a living “unprompted and uninvited.” There are passages on Fendi’s history alongside long musings about Sex and the City; penguins shitting at the indoor Ski Dubai; undercover happiness police harassing her with vouchers (part of Dubai’s initiative to rank among the world’s happiest); gold digger academies where people pay a thousand a week to learn how to find and keep outrageously wealthy men. The full effects of living without the socialist scaffolding take effect. She has a panic attack while listening to her meditation app:

Was this anxiety temporary? She didn’t think so. Dubai, after all, was a transient city. This was not somewhere you were encouraged to stay. If you were let go from a job, you had thirty days to find a new one or you had to leave the country.

And it goes on and on, all while her alienation from the world, and especially her daughter, remains and deepens, making her question whether she’s fulfilling her maternal duties as contractual obligation rather than instinct. The city is utterly claustrophobic: “She couldn’t have a future in Dubai, it was impossible.”

It posits an interesting conundrum: Whether the insanity is brought on by the artificiality of the city, the Gulf, the government, a government, capitalism, communism, sex, gender, being a woman, being a mother, being an immigrant, being a Kurd, being a person, or simply being. It forces you to abandon your immigrant fiction lens in the face of the sheer onslaught of information — especially during the successive chapters from Mohammad’s and Laika’s perspectives, where pages-long diatribes on international banking and stock market manipulation come into full swing. Whole chapters are devoted to selling carbon credits to oil companies. You’ll find yourself emotionally stepping back initially, attempting to distill patterns and construct some internal thesis from the system’s moving parts. But unlike the abstractions in other financially-focused postmodern novels, such as William Gaddis’s JR, the characters in Hyper are well developed enough that they immediately ground the narrative in an emotional reality, providing painfully honest portrayals of issues that, as an immigrant, feel unsettlingly familiar: social isolation while living in exile, double digit bank balances, eroding relationships with friends and family back home. The novel tugs at your heartstrings and makes you feel monstrous for trying to reduce the characters in service of your own intellectual curiosity.

Hyper, like all great postmodernist texts, refuses to be read simply. There is no all-encompassing interpretation, tidy summation, or take-home message. There’s something frightening about fiction written this candidly; it makes our morbid fascination with dissecting tragedies impossible to ignore, even as we recognize that immigrants, and Kurds especially, have been mangled into literary specimens, byproducts of statelessness serving as convenient political and economic vectors.

Ismaïl, let me do you a favor and lay out the premise for Hyper II so you don’t spend another decade writing it (no need to thank me in the acknowledgments but you can name a chihuahua after me, fictional or not): Siver, Mohammad, and Laika (the space dog this time, not their sibling) reunite, learn the errors of their ways, and open a Marxist–Leninist themed kebab house called Rafiq’s in Dubai’s Global Village with the goal of worldwide franchising to end capitalism and reclaim Kurdistan once and for all. Rafiq’s very own Café Riche.

Trust me3, it’s what Rafiq himself would’ve wanted.

Sources & References

The citation style used by Agri Ismaïl in his novel Hyper felt like the correct format for this review:

1 Much of this passage is self-plagiarized from my thrice rejected essay, On Why a McCrispy from the Capital Costs $7.29 and Other Grievances from a Miserly Kurd (soon to be resubmitted to The Atlantic).

2 Quoted from her interview with The Common. Also, If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English and Washes, Prays are excellent. Please read them.

3 Don’t.