The October 2025 issue of The Markaz Review examines the multifaceted nature of friendship — intimate or communal, joyful or bittersweet.

Friendship has always held a special place in Arab culture as crucial lifeline and safe haven. Shaped by cultural values, social structures, and historical contexts, Arab narratives about friendship often underscore the way we gather, the value we place on loyalty, and the comfort we get from shared laughter around the dinner table. And yet, our connections also mirror the impact of broader forces, including war, patriarchy, social class, displacement, and sometimes deep-seated loss. In this issue, we examine the multifaceted nature of friendship — whether intimate or communal, joyful or bittersweet. While some pieces celebrate this bond, others explore its idiosyncrasies and betrayals. All cement its power.

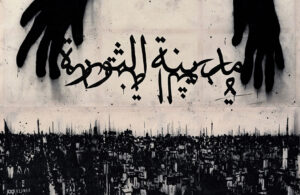

In the shadow of ongoing violence and genocide, dedicating an entire issue to friendship might seem trivial, an escape from what is happening, but we think it’s crucial. In fact, it is a quiet act of resistance — a way to honor the relationships that nourish art, empathy, and memory in a world that tries to erase them. Especially now, more than ever, friendship is survival. Friendship in Arab/Middle Eastern life, in our literature, and across our histories, has never been separate from struggle. When we experience grief, we share it collectively; it’s how we keep each other alive and push and prod one another to envision a future still capable of holding space for joy, for trust, and for love.

As we observe the Freedom Flotilla being branded as terrorists by the Israeli government for undertaking an act of extending friendship and humanitarian aid to those in need, we can’t help but reflect on the decline of genuine human connection and the spirit of solidarity. This situation raises profound questions about the values we hold dear and the extent to which society is willing to embrace compassion. In an era where the lines between allyship and hostility seem increasingly blurred, it is disheartening to see those who dare to reach out and help being met with suspicion and hostility. What has happened to the fundamental principles of empathy and understanding that once united us in our shared humanity?

In Lament for My Dear Cousin and Friend in Tulkarm, Palestinian writer Thoth (pseudonym for the writer’s safety) reflects on the loss of a cousin and childhood companion amid the Israeli military’s invasion of Tulkarm in the West Bank. A friend was taken while the world looked on, as hashtags trended, and yet, nothing changed. This piece captures a grief that is both immense and profound, intertwined with a deep, irreplaceable love. It portrays the harrowing reality of having to mourn a loved one while the violence that claimed them continues unabated. So, what does friendship even mean in this context? It means bearing witness, even if it breaks you. It is in naming the friend who is gone. Remembering their presence and their absence. It is in recognizing that friendship does not end with death, distance, or borders. It lives — and thrives —in the stories we carry about one another.

Our senior reviewer, Katie Logan, discusses two recent reissues reflecting on Palestinian resistance and solidarity, in Revolutionary Reissues: Enemy Of The Sun and Leila and the Wolves.

Palestinian Emirati, Lebanese-born multidisciplinary artist Noura Ali-Ramahi grieves as she witnesses the heartbreaking starvation in Gaza from Abu Dhabi. In her essay “Blue, The Arabian Red Fox”, she records the bond between herself and an Arabian red fox she befriends in a dilapidated golf course; two beings, so different in nature, finding comfort and understanding in each other. A friendship that asks for nothing yet gives everything in return. She writes, “Blue … represents everything that is still honest and pure and real and free in the world. When I sit with her while she delicately pierces a hole in an egg so she can suck the white and yolk through the shell without spilling a drop, I am filled with awe. For a few seconds, I forget an image that is always with me, of starving children in Gaza picking over spilled flour from the street as they cry in hunger and despair … and I share a story on Instagram. It might show a fox, but the photograph is about Palestine. It is my small attempt to crack the mighty algorithm and resist, from the shadows.”

All around us, friendships that have lasted for years are fading away across borders, through screens, and even in classrooms. Silences feel louder than ever. As narratives on genocide, war, and displacement become polarized and politicized, people are paying a hefty price for choosing to embrace a compassionate stance towards those suffering. Christina Adranly’s essay, “You Want Your Friends to See Who You Really Are,” powerfully explores her experiences as a Christian American Palestinian in a wealthy, predominantly white town. She navigates the painful divide between superficial acceptance and genuine solidarity, detailing the cost of fitting into unwelcoming spaces. A betrayal by a close friend deepens her disillusionment. Ultimately, she realizes she’s not only the first in her family to achieve the American Dream but also the first to understand the duality of a system that advances and constrains at the same time. In a moment of clarity, she fully understands what it means to be spoken for — and what happens when she speaks for herself.

An exploration of this concept can be found in the insightful book review by Natasha Tynes, who discusses Sara Hamdan’s debut novel, What Will People Think?, in which the author writes about taboo topics such as premarital sex, virginity, asexuality, and intercultural marriage with both sensitivity and humor. In her critique, Tynes argues that the book “encapsulates how Arab Americans must constantly navigate linguistic landmines, turning potential misunderstandings into sources of humor rather than of shame.”

As we approach the two-year mark of a devastating genocide, as Gazans continue to starve, as we continue to rage, as cities are flattened, and as names turn to numbers, it’s only natural for the world to demand we focus solely on stories of survival or resistance. As such, while the fiction in this issue may seem apolitical at first glance, it reveals a deeper truth: each narrative actively resists erasure and marginalization. These stories are a testament to the resilience of voices that strive to be heard in a world that seeks to overlook them.

We present a coming-of-age excerpt from French-Algerian author Fatima Daas’s latest novel Play the Game, expertly translated for TMR by Fellow Lara Vergnaud, a story that captures the nuances of growing up queer and Muslim in France. In addition, Vergnaud has interviewed the author, in Fatima Daas on Playing the Game. Complementing this is Youssef Manessa’s story, Somewhere Other Than Here, which makes sense of the complexities of a hierarchical, class-obsessed Lebanese bourgeois society when two childhood acquaintances reconnect. As old grudges resurface, they must first navigate their friendship before exploring the possibility of love.

In a digital age dominated by screens and virtual interactions, one must ponder: where does true friendship reside? As we navigate a landscape filled with social media connections and instant messaging, the essence of genuine companionship often feels elusive. Are the bonds we forge online as meaningful as those formed in person? How do we cultivate trust, empathy, and understanding in a world where our interactions are mediated by technology? In the excerpt from Ahmed El-Fakharany’s novel, All You Need to Know About X, translated from Arabic by Nada Faris, we see how the glow of screens and the flow of online exchanges can create an illusion of deep connections. Virtual friendships barely skim the surface of true intimacy, fostering relationships that reflect more of ourselves than the realities of others. This begs the question: are we genuinely connected, or are we simply sheltered from loneliness by a facade? In the short story A Day in Damascus, the Jordanian writer Sanad Tabbaa offers a more playful perspective on the topic. His narrative follows an arthouse film that sweeps through the Syrian capital, captivating audiences. Accompanied by a special console that comes with the movie, viewers can see characters from different films cross paths, intertwining their storylines and forging surprising friendships along the way.

In the short story Come See the Peacock, Finnish Iraqi writer Aya Chalabee brings to life a spectral friendship remembered in exile, and a profound sense of longing. Conversations with the ghosts of the past are wrapped in nostalgia for the homeland where Chalabee’s protagonist walks familiar streets only in dreams, speaks old names, and feels the aches of places that no longer exist as she knew them. In missing home, she befriends its echoes.

Arabic literary works, particularly in modern or postcolonial contexts, often portray male friendship as a vital form of social and political solidarity, rooted in shared struggles and a collective identity. In Elias Khoury’s Little Mountain, set during the Lebanese Civil War, friendships among fighters reveal a mix of intimacy and emotional distance, reflecting shared trauma and distrust. Similarly, Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North presents a fractured friendship that symbolizes a loss of innocence and personal guilt, influenced by societal norms of masculinity. Contemporary Arab women novelists often employ the theme of friendship to explore personal lives, challenge patriarchal norms, tackle taboo topics, and maneuver through restrictive societal expectations. In works like Hanan al-Shaykh’s Women of Sand and Myrrh and Radwa Ashour’s The Woman from Tantoura, which focus on themes of political violence and memory, it is the bonds of female friendship that help sustain the protagonists through exile and personal hardship. When these bonds of sisterhood weaken, the fallout means the breakdown of the community that once provided comfort and support. As such, we’ve compiled a booklist featuring 10 novels that explore the multifaceted nature of friendship: tender, tumultuous, redemptive, and complex. Together, these books offer a unique perspective on the power of connection.

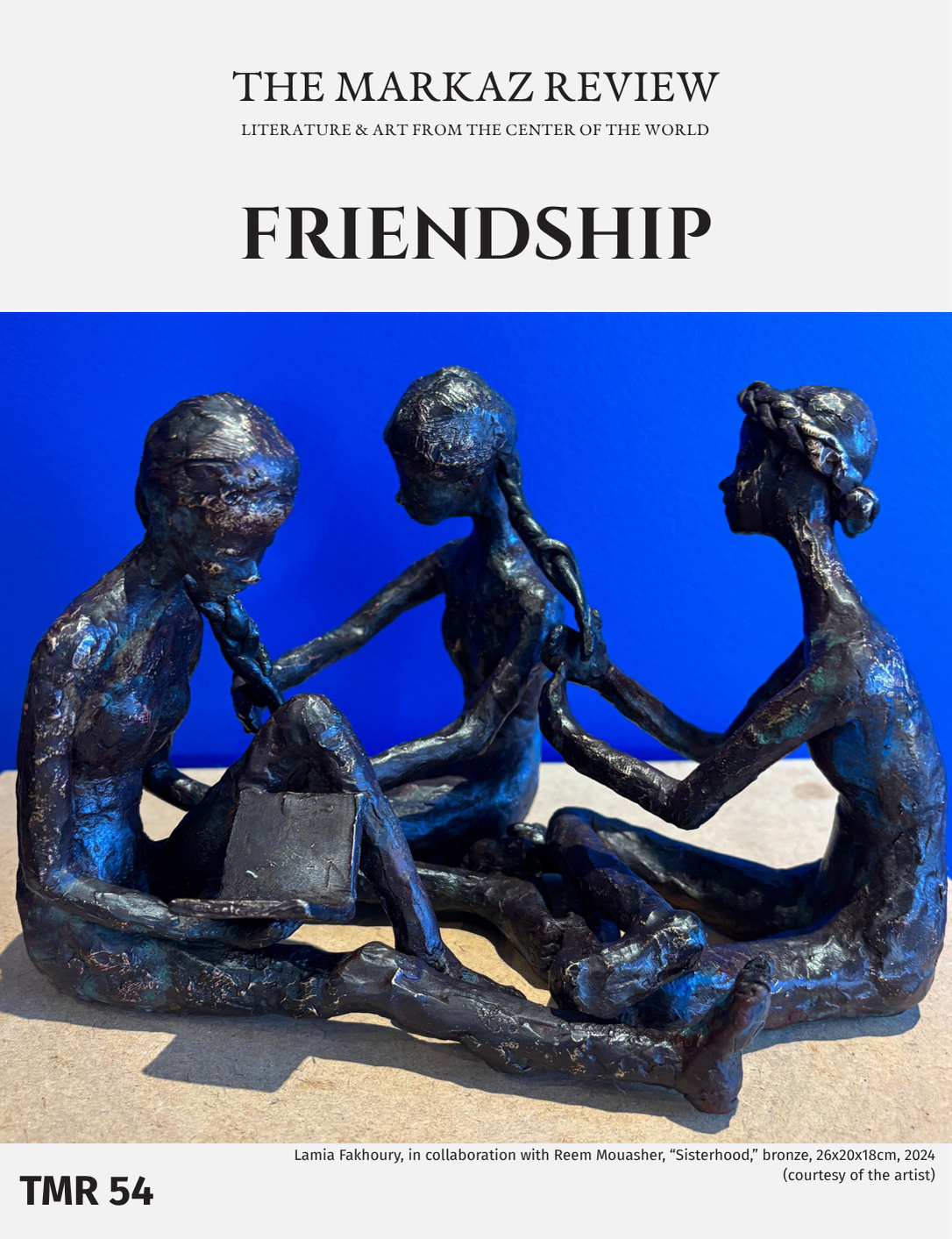

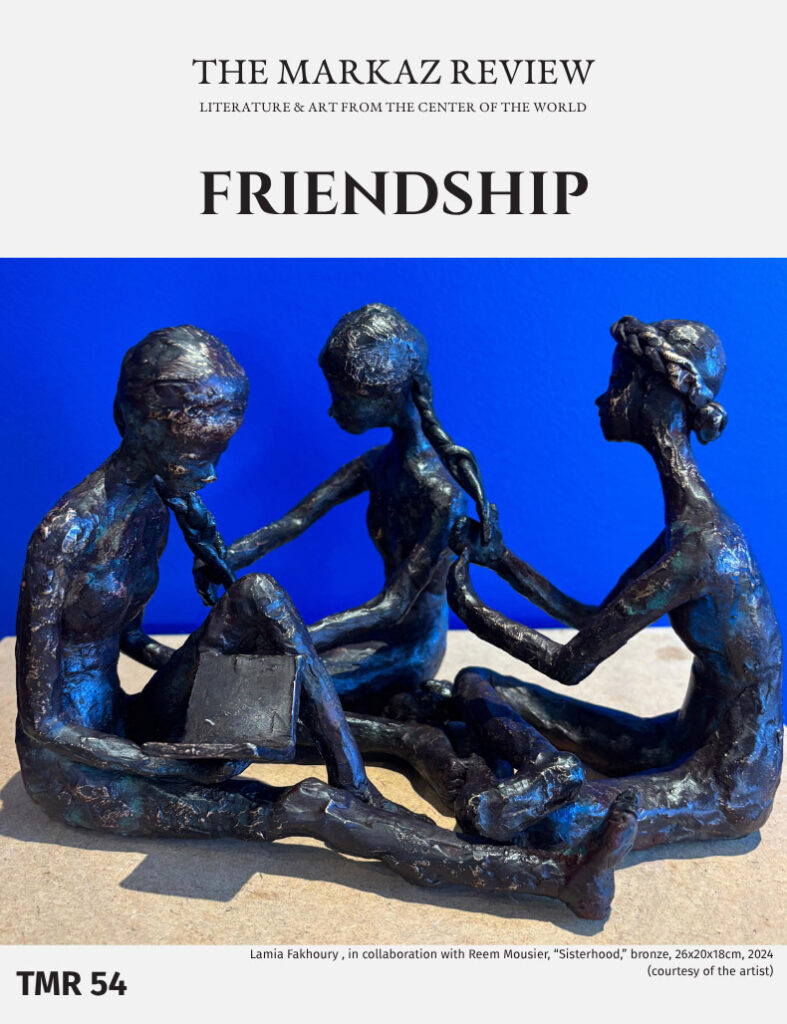

They say it’s never too late to make new friends, and I’ve recently discovered just how true that is. Our featured artist, Jordanian sculptor Lamia Fakhoury featured in Lamia Fakhoury: Holding Space and Working Together , is a newfound kindred spirit who turned out to be a childhood schoolmate of my husband. Knowing her now is proof that friendships wait patiently in the wings of old stories.

Unlike any other relationship, friendship is chosen, sustained not by obligation but by shared moments, mutual care, and trust. This issue is a celebration of that choice and of the texts that speak to each other like old friends. In a world that often feels fast, fragmented, and fiercely individual, we wanted to slow things down and turn our attention to something quietly powerful: friendship. The bond that reminds us that even in the most brutal circumstances, we remain capable of sustaining and building connections, even if it also means letting some go their own way. This resilience, too, is an essential part of our cultural legacy.

—Rana Asfour, Managing Editor of TMR