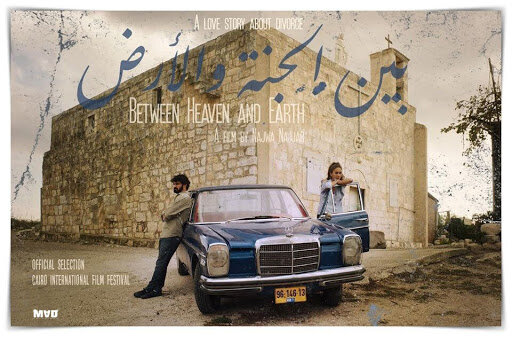

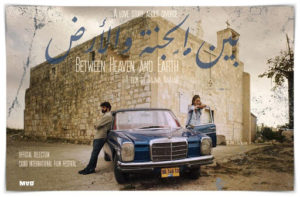

Contributing Editor Ammiel Alcalay reviews writer/director Najwa Najjar’s third feature film (after Pomegranates and Myrrh and Eyes of a Thief) recently screened during the Arab Film and Media Institute‘s Arab Film Fest Collab. Congratulations are in order!

Ammiel Alcalay

Films emerging from very particular and complex historical, political, and cultural circumstances often streamline and sometimes even dumb down in order to travel to audiences outside the realm of the cognoscenti. Directors too seldom forge an engaging enough plot, charismatic characters, and settings poetic enough to carry all the particulars forward to viewers who simply may not have the tools to grasp what might be at stake.

But Palestinian director and writer Najwa Najjar brilliantly manages to thread this needle in her third feature, Between Heaven and Earth, now on the festival circuit after having, quite rightfully, won the Naguib Mahfouz Best Screenplay Award while premiering at the 2019 Cairo International Film Festival. Ostensibly the story of an estranged but quite inextricably bound Palestinian couple trying to file for divorce, Between Heaven and Earth proves to be a finely layered and profound meditation on some of the most intractable and moving elements that have gone into what one might simply call the Palestinian existential condition. Part road movie, part mystery, part thriller, the film uses generic situations to burrow more deeply into various ways that untenable conditions can be resisted and not become yet more fodder to explode from within the possibilities of remaining human.

Shadowing the whole narrative is the fact that the couple—because Tamer was born in Beirut—have been living together in the occupied West Bank, unable to travel freely to and from Salma’s family home in Nazareth. It is only when they decide to file for divorce that Tamer is finally given permission to enter Israel, and it is this journey on which the film’s narrative hinges. What makes the film stand out, in addition to superb acting, crisp dialogue, and the consistently engaging visual narrative, is Najjar’s willingness to push the limits of plot and subplot, to at least begin the attempt of delineating the basic complexities involved in the situation, even at the risk of occasionally falling back on a stereotype or two here and there.

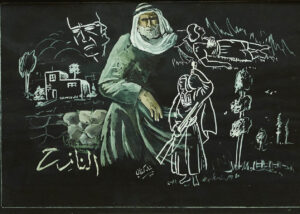

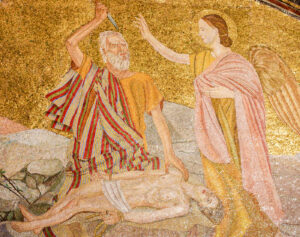

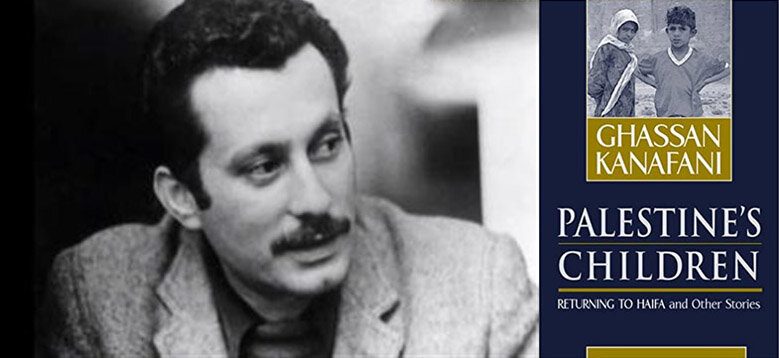

Salma, beautifully played by Mouna Hawa, is a Palestinian with Israeli citizenship, daughter of a Communist activist who errs on the side of his daughter’s freedom while Salma’s mother would rather see her daughter settled, bringing up a family. Salma’s husband Tamer, played to a slow burn by Firas Nasser, is the son of a Palestinian cultural icon and activist assassinated in Beirut, during one of many Israeli led purges of Palestinian intellectuals. By naming Tamer’s father Ghassan, Najjar obviously hints at Ghassan Kanafani, the great Palestinian writer and revolutionary assassinated in Beirut in 1972 and whose novella Return to Haifa, resonates throughout the film in various ways.

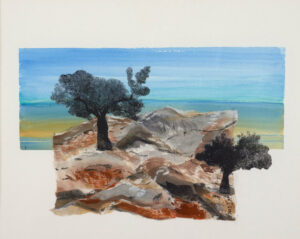

As Tamer finds out that his father had a relationship with a somewhat mysterious Iraqi Jewish woman who had another son named Tamir, Najjar opens up two themes that are far too seldom depicted anywhere: that of the “missing” children, Arab Jewish babies reported deceased to their parents but actually kidnapped and given by the Israeli state for adoption to childless European Jews, and the activism of Arab Jews, particularly from Iraq, in the Israeli Communist Party. These themes resonate throughout the film as the couple find parts of their identity sequentially constructed and deconstructed, to the point when they finally reach the destroyed village of Iqrit, the remains of which are still guarded over by young Palestinians. There Tamer sees a memorial to his father, heretofore unknown to him.

Filmed over the course of 24 days, with four arrests of crew-members, the narrative also works because the journey is clearly one of discovery for the director as well. As Najjar noted in an interview: “It’s a journey for me, it’s a discovery. I have been denied to know Palestine and to know the Arab world the way that I want to so each movie that I make is really an exploration, I’m trying to understand something, and I hope that I’m able to communicate that to audiences.” By allowing herself to write through a script depicting this process of discovery, Najjar is able to significantly up the ante on the kind of detail an audience might be able to assimilate. We eagerly look forward to her next directorial project, Kiss of a Stranger, a musical that she wrote during lockdown, set during the golden age of Egyptian cinema in the 1930s.