"I left Damascus ten years ago, when I was 16 years old and never returned. I spent the majority of those ten years in Naarm (Melbourne, Australia) reconstructing what home is, building and demolishing, remembering and forgetting, looking in mirrors and recognizing new sets of eyes."

It has been 65 days since I left Damascus for the second time. I think about shaving my head every single day, and stare at random grocery bags in my kitchen while denying the looming panic attacks. I have been breaking down and bursting in tears since December 8, 2024. The tears might scar at some point, but nothing compares to crying in Damascus. Tears make sense in Damascus.

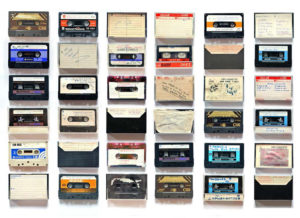

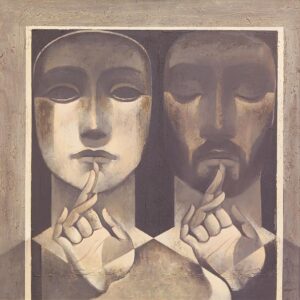

I bought a new visual diary that I have dedicated to “the return” at the beginning of January 2025 after the fall of the Assad regime and before booking a flight to Damascus. I left Damascus ten years ago, when I was 16 years old and never returned. I spent the majority of those ten years in Naarm (Melbourne, Australia) reconstructing what home is, building and demolishing, remembering and forgetting, looking in mirrors and recognizing new sets of eyes.

I was only able to identify that those eyes belonged to my different exiled selves when I started preparing for this return.

You don’t return as one. You return as many — tears, streets, slaps, scars, dreams, screams, and suitcases. I felt nauseated every time I thought of all the places I wanted to visit, and I wanted to disappear before even getting there. I was swallowed by enormous emotional doors, opening and closing so quickly in my head. I felt like I could almost smell the rain or the jasmine. But then — “I shut my eyes, and all the world drops dead,” — Sylvia Plath. I have forgotten how it feels to be in Damascus, as if I had never been there at all.

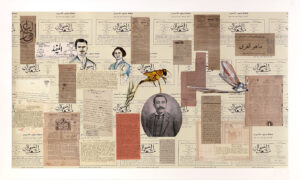

When I started working on my visual diary, I did some research on artists who returned to their home countries after a period of exile. I found an installation entitled Where We Come From, 2001-2003 by Emily Jacir. A Palestinian artist asked Palestinians in exile: “If I could do anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it be?” She gathered all the answers and went to Palestine and did everything they asked her to do and documented it through photography. I thought of all the Syrians wishing to return to Syria who are stuck in exile because of travel documents and other restrictions. I remembered friends who mentioned places or names of streets that I’ve never been to in Damascus or that I couldn’t recall.

I’ve carried an imaginary construction site in my head for the past ten years — constantly building and demolishing homes. The building was never complete, never polished. Just scattered bricks, always shifting, always unfinished.

John Locke wrote: “A person’s identity only reaches as far as their memory in the past.” Reading that made me feel like a distorted freak. There was always something missing or ambiguous in my memory of Damascus, which later made me feel like I had never really been there. I hadn’t been to Qudsaya* before — and yet “Qudsaya,” the song by Kulna Sawa, has always been one of my favorites. I related to friends who lived there through that song. Relating to other Syrians in exile felt so important to me, because I could see how we are deprived of completing our Syrian portraits — depending on when we left Syria and how old we were. I finally visited Qudsaya when I returned to Damascus, and now I can see it when I close my eyes. Like the way I see Mazbouta café and Dr. Oussama Ghanam sitting there with the biggest heart and warmest smile. I sewed part of the self-portrait.

Returning to Damascus was not simply returning home. I’ve carried an imaginary construction site in my head for the past ten years — constantly building and demolishing homes. The building was never complete, never polished. Just scattered bricks, always shifting, always unfinished. But the moment I landed in Damascus, the construction stopped. For the first time, I gave up on gathering those scattered bricks in my head. Damascus was an open space for grief, the imaginary one they tell you about in therapy. The safest and scariest space for grief. You grieve the time, the people, the leftovers of who you were, and no one could ever hold you as tightly as your exiled selves do. They recognize you and your pain, while no one ever could in Damascus. I don’t remember how many times I wept in the streets. Basically, every time I realized that I am in Damascus, I broke down.

Traumas embody Damascus. I couldn’t take in the city without this crushing sadness of what-ifs and seeing silhouettes of people I don’t know — people who were killed, kidnapped, tortured, and forcibly disappeared. The absence of the regime and its monsters in the city is captivating, almost unbelievable. Yet, the trauma lingers like street dust — rising, swirling, and settling upon you as you walk. Who said we can’t mourn and stand in sadness and grief for a while just to realize what has happened? Am I a killjoy? I might be. But I couldn’t help but think of all the scenarios that could have saved the people who are no longer with us, and the people who are still with us but in fragments. I carry their sorrow with me. I carry every single person whose story I’ve heard. I have been carrying and carrying for ten long years, playing Chavela Vargas’s Paloma Negra in my head and weeping like her. I remembered Vargas in Damascus, when I saw an old lady in Al Marja Square, sitting on a chair and holding a radio playing a religious hymn up to her ear, praying with her other hand to God. I wanted to mourn like Vargas next to that old lady. My exiled selves help me make sense of pain as they walk with me. One of them reminded me of Vargas, and another reminded me of Joan Mitchell’s paintings when I almost broke down five hours before my flight to Damascus. Picturing pain gives you the ability to grab it — and that is better than pain grabbing you by the throat. I guess.

Being a woman in Damascus makes you angry, makes you want to fight, scream, bleed with pain and anger. Pain and anger. And anger. Political, social and patriarchal violence against women is very visible in every aspect of women’s daily lives and everyone around them is complicit with this violence. I haven’t sat with a single woman in Damascus without feeling like I might explode from frustration after hearing their stories and the struggles they have faced before and after the fall of the Assad regime. Yet they remain the strongest of all. Their strength held me tightly every time we had coffee. Coffee in Damascus tasted salty all the time.

I have been thinking of death a lot since coming back from Damascus — my own death. As if Damascus has reminded me of the fact. Especially during the last two days of my visit, I was saying goodbye to people feeling that being abroad is not what is going to stop me from visiting or seeing them again — but death. I am traumatized by farewells. It started at a very young age, and I am well aware of it. About a year ago, I noticed that I had begun dissociating during goodbyes — maybe as a defense mechanism (one of my exiled selves?). Farewells feel like peeling my skin off — willingly. Every day since I left Damascus again, has felt like one long farewell that hasn’t ended yet. Like writing about Damascus now.

* Qudasaya was a rebel stronghold under Assad and underwent a four-year siege. After the fall of the regime, Israel bombed the town. [Ed]