Select Other Languages French.

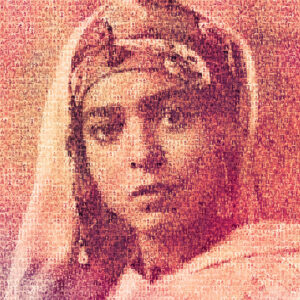

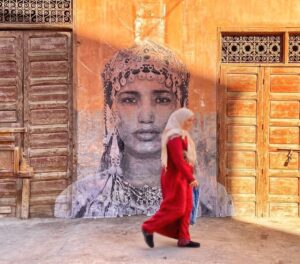

A groundbreaking Arab writer who died 10 years ago this month, Fatima Mernissi insisted that feminism is not a western idea but deeply rooted in Arab and Muslim society.

There is a touch of France in downtown Rabat. Cafés line the parks, couples sit on park benches, and bookstores stock new releases from Paris. Kalila wa Dimna, Morocco’s oldest bookstore, is a central attraction, especially following the start of the school year. Cultural life in Morocco is still very French-influenced. “We also have Fatima Mernissi’s books in Arabic,” says Souad Belafraj, one of the owners of Kalila wa Dimna. Of course, she knew Mernissi, one of Morocco’s most celebrated authors, who often presented her works at readings in the bookstore.

Like all bookstores worldwide, Kalila wa Dimna is struggling with the fact that people read less today than they did during Mernissi’s heyday. And Mernissi’s memory also vies with the fact that the Moroccan middle class currently has very different problems: the cost of living is rising; young people can’t find work; education and hospitals are in bad shape, while at the same time stadiums are being built for the 2030 World Cup. The country has been shaken recently by youth protests against corruption and nepotism. Still, “Mernissi must not be forgotten,” says Belafraj. “And she should be more revered; she deserves it.”

Says Mouna Anajjar, editor-in-chief of the cultural magazine I Came for Cous Cous, “Fatima Mernissi emphasized the richness of knowledge passed down orally by women in Morocco — stories, songs, weaving, and embroidery — and the fact that it often remained invisible to the academic world. She showed how this living memory is, in reality, a true source of thought and creativity.”

No events are planned to mark the 10th anniversary of her death, on November 30. However, a Fatima Mernissi Chair has been established at Mohammed V University in Rabat; the well-known author Driss Ksikes has written a play about her life; and in 2022, the film Fatema, la Sultane Inoubliable was released in cinemas. Beyond Morocco, Mernissi is known as one of the first female postcolonial voices from the Global South.

Fatima Mernissi’s themes have to do with gender roles in the Arab world and the search for a distinct Arab feminism. Her criticism not only of Moroccan patriarchal society, but also of Western colonial stereotypes about Arab women, inspired renowned women of her generation, among them activist Aicha Chenna, founder of Association Solidarite Feminine, scholar Fatima Sadiq at Fes University, and publisher Layla Chaouni of Le Fennec.

Born in Fez in 1940, Mernissi belonged to the first generation of women after Morocco’s independence in 1956 who had opportunities for higher education and university attendance. Her bourgeois family gave her the self-confidence of a Fassi: Fez is home to what is probably the world’s first university, founded by a woman in the 9th century, and its inhabitants enjoy special prestige in Morocco.

Mernissi began her studies at Mohammed V University in Rabat. In 1966, she received a scholarship to study sociology in Paris and then, from 1970, at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. Her doctoral thesis, published in 1975 under the title Beyond the Veil: Male-Female Dynamics in Modern Muslim Society, established her reputation as an independent thinker. It was groundbreaking in its examination of European stereotypes about Arab women.

In 1974, she returned to Rabat and was appointed to the chair of sociology at the university where she had begun her studies. During her years of teaching, she became a central intellectual figure in Morocco, well connected and open to non-academic spheres of life. “Ten years after her death, we can better appreciate how central her role was,” says poet and former president of the Association of Moroccan Writers, Hassan Najmi. “It is above all her independence that made Fatima Mernissi an icon of intellectual thought in Morocco.” Mernissi never accepted a state award, and during the “years of lead” under Hassan II, she invited colleagues who had been removed by the regime from their posts at the university to conferences. She was neither tempted by money from the Gulf states nor discouraged by the temporary banning of one of her books — Le harem politique: Le Prophète et les femmes (translated in English as The Veil and the Male Elite: A Feminist Interpretation of Women’s Rights in Islam) was banned in Morocco and other Arab states for more than a decade after its publication in 1987. She wrote:

Is there a nascent female liberation movement similar to those appearing in Western countries? This kind of question has for decades blocked and distorted analysis of the Muslim woman’s situation, keeping it at the level of senseless comparisons and unfounded conclusions. It is a well established tradition to discuss the Muslim woman by comparing her, implicitly or explicitly, to the Western woman. This tradition reflects the general pattern prevailing in both East and West when the issue is “who is more civilized than whom.”

However, this also left her writing open to different interpretations, says author Driss Ksikes, a long-time friend and companion. Mernissi’s writing has many facets, says Ksikes. But a common thread for her was to demonstrate from different perspectives how “feminism is not a Western category.” The fact that she sometimes got stuck in old patterns herself becomes evident in her best-known work, the autobiographical narrative Dreams of Trespass: Tales of a Harem Girlhood, which was published in 1994 and has been translated since into 25 languages (in the UK the title is The Harem Within: Tales of a Moroccan Girlhood).

The story is set in a house in Fez, where the women live separately from the men of the family, and is written from the perspective of a seven-year-old girl — presumably Mernissi herself — who dreams of overcoming the limitations imposed on her. Mernissi writes that she wants to show that even Arab women who grew up in seclusion during the colonial era were by no means powerless.

Despite its overtly feminist impulse, the book sparked criticism that Mernissi was perpetuating Orientalist stereotypes in it. Though she was not enthusiastic about seeing the word “harem” in the title of the English editions, she agreed to her publishers’ request because it would help sell copies, as Raja Rhouni notes in Secular and Feminist Critiques in the Work of Fatima Mernissi. Nonetheless, French literary scholar Carine Bourget argues that Mernissi’s autobiographical narrative fulfills the cliché of a woman from the Third World longing for a Western lifestyle. Scholars including Palestinian American anthropologist Lila Abu-Lughod are in tune with the critique. The Harem Within also confirms stereotypical views of Arab-Muslim culture as being thoroughly misogynistic, because, as Abu-Lughod writes, the novel is based on the idea of liberation “against all restricting forces of tradition,” and uses familiar terms such as tradition and modernity, harems and freedom, veiling and unveiling “by which the East has long been apprehended (and devalued) and the West has constructed itself as superior.” Such ideas have helped justify Western interventions in the Arab world, such as in Iraq in 2003, writes Bourget. The motive of wanting to “save” Arab women repeatedly crops up in the justification of military interventions or colonial conquests — from the British in Egypt and the French in North Africa to the more recent US interventions.

Dialogue between western women and women of the Middle East has always been difficult. But today, two years after the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent Israeli genocide in the Gaza Strip, the rift between western and Arab women seems irreconcilable.

Fatima Mernissi oscillated between two poles. She wanted to give Arab women a voice in a patriarchal society that condemned women to silence in the name of culture and Islam. At the same time, she argued against the Eurocentric notion prevalent in the West that Europe invented feminism and that Arab women are merely passive victims without any power of their own and in need of saving.

While her early work focused more on criticizing her own patriarchal society, her later works dealt more with Western societies. The experience of the Gulf War and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein by the US in 2003 made Mernissi more critical in her examination of the West. She was also troubled by the fact that she was often asked in interviews in Europe why she did not want to become like Western women.

In her later works, she turned more strongly to Arab history and culture. Her search for an Arab identity in the modern world struck a chord in the postcolonial nation states of the region. In her engagement with Islam and its history, she increasingly arrived at a more nuanced attitude toward religion and women’s rights.

She understood Islam in its fundamentals, especially the Quran, as egalitarian. However, she believed that over the centuries, the Quran had been distorted and interpreted in a misogynistic way by male scholars. With this view, she provided starting points for an Islamic feminism that has strong voices in Morocco today. This movement, which has been growing stronger since the 1980s, reflects an increased desire in the region to establish women’s rights within an Islamic framework.

This feminism is not directed against the West and, in its practical demands for equality, often comes to similar conclusions as liberal Western feminism based on UN conventions. However, the reasoning takes into account that women’s rights are at stake in a context where religion plays a central role. This is how Asma Lamrabet, today the most prominent voice of independent Islamic feminism in Morocco, puts it. She was a friend and companion of Mernissi.

However, with her understanding of Islam as a religion deeply rooted in justice, Mernissi also rubbed the rulers the wrong way. When The Political Harem was published in 1991, the book was the talk of Morocco, says poet Hassan Najmi. However, anything related to Islam is a sensitive issue for the royal family. The Political Harem was initially banned when it was published. Mernissi’s demands for justice were rightly understood as thoroughly political.

Internationally, the ban helped to make her works known beyond the Francophone world. Fatima Mernissi was a frequent visitor to Europe and cultural exchange was important to her. In Scheherazade Goes West (2001), she used the word “harem” as a metaphor for the limitations imposed on women, which can also consist of invisible walls. “Mernissi was interested in creating a counter-narrative,” says Driss Ksikes. “She questioned the idea of silenced Arab women and rediscovered their voices in Islamic history.” But in Sheherazade Goes West, she also held up a mirror to the West, because even in Europe and the US there is a “harem” for women. She described it as a “size 38 harem” and criticized the objectification of women’s bodies by a capitalist system driven by commercial interest.

Dialogue between western women and women of the Middle East has always been difficult. But today, two years after the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent Israeli genocide in the Gaza Strip, the rift between western and Arab women seems irreconcilable. The accusations from the Arab side are great, lamenting the lack of solidarity from Western feminists in the face of Palestinian women having to undergo caesarean sections without anesthesia and to give birth to their children amid the rubble of their destroyed homes. The double standards of the West have led to a disillusionment in the Middle East with so-called liberal Western values. Today in Morocco, even secular feminists are calling for humanistic values to be sourced from the Islamic tradition and for a distinct Arab path to feminism to be found, following in the footsteps of Fatima Mernissi.