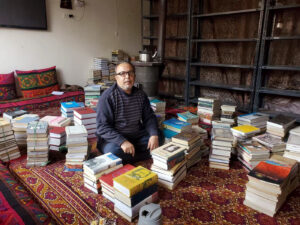

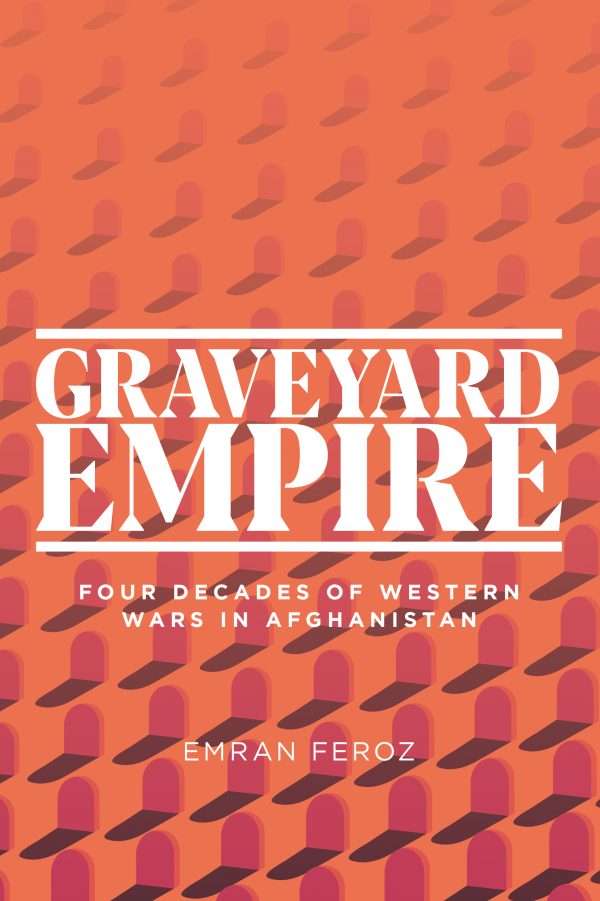

Operation Enduring Freedom on October 7, 2001 marked the beginning of the so-called “War on Terror” in Afghanistan, which to date has become the longest war fought by the USA and its allies, with thousands of deaths and injuries. In his new book Graveyard Empire, reporter Emran Feroz describes this 20-year war from an inner Afghan perspective. From speaking to Hamid Karzai and Taliban officials to interviews with affected citizens who suffered the most from this war, Feroz gives a true picture from a non-western point of view — one that is rarely heard in mainstream media reporting. It makes one thing more than clear: The US’s “Saigon moment” in Kabul in August 2021 was more than foreseeable.

Graveyard Empire: Four Decades of Wars and Intervention in Afghanistan, by Emran Feroz

Interlink Books 2024

ISBN 9781623711061

Even during the final days of the American occupation, anyone who happened to be in Kabul would have noticed the presence of numerous military vehicles forming columns and aggressively speeding through the capital’s gridlocked traffic. Heavily armed soldiers could be seen inside them, probably already thinking about their next deployment. The heavy SUVs bore the initials NDS, short for National Directorate of Security, the domestic Afghan intelligence agency built by the CIA after 2001.

A de facto extension of the US intelligence agency that created it, NDS regularly terrorized the Afghan population. “They raided his house in the middle of the night and just took him,” I was told by Mohammad Rahim, who requested that I not use his real name. One of Rahim’s cousins who had himself served in the army was arrested without cause by NDS units in March 2021. Armed men had landed a helicopter on the roof of his family’s home before forcing their way in and kidnapping him. Following the incident, his family moved out of their Kabul district in fear.

“Why are innocent people just being kidnapped? We’re all worried and haven’t been able to contact my cousin since,” Rahim said. A similar operation on January 5, 2020, ended in a massacre. Around 7:30 that evening, NDS units raided a house in a famous Kabul district. A few hours later, five people were dead. “They attacked our house in an extremely brutal way, leaving a bloodbath,” one of the eyewitnesses later told me. Among the dead was a man named Amer Abdul Sattar, a famous mujahideen commander who had fought the Soviets in the 1980s and been an important ally of the Afghan president Ashraf Ghani for some time. Sattar was from Parwan Province to the north of Kabul and had been staying with friends in the capital on the weekend when the attack occurred. “Sattar and his son were our guests. They were murdered along with my father and brother,” I was told by Shafi Ghorbandi, the son of the murdered host. All evidence suggested that Sattar had been the target of the NDS raid. Even his son was murdered by the special units. Yet the question of why a political ally of Afghanistan’s president had become a target of the latter’s own intelligence agency remained unanswered. Shortly after the raid, Sattar’s family was received by Ghani in the Arg, Afghanistan’s presidential palace, and the president promised an investigation into the massacre. At the same time, the NDS attack in Ghorbandi’s house also became the subject of an intense debate in parliament. Several members of parliament demanded not only an investigation to the case of Sattar but also the other brutal raids that had taken place in Afghanistan.

In one of these raids that had occurred in the same month in a village in Laghman Province, the secret units had killed an elderly man and kidnapped his four sons. These units belonged to a virtually impenetrable counterterrorism network that the CIA had installed throughout the country.

Over the two decades of the occupation, the CIA constructed a massive intra-Afghan security and surveillance apparatus. The agency had stations at several locations in the country, including in Kabul, at Jalalabad Airport in the east, and in the city of Khost in the southeast. Spy balloons dotted the sky, creating a dystopian atmosphere that eventually became a normal part of life. The NDS commanded numerous shadowy paramilitary units that regularly fanned out across the country to conduct operations. The hierarchy within these structures was mostly shrouded in darkness and was a frequent topic of speculation. Even various high-ranking Afghan officials, including the president himself, were presumably not privy to many of their activities. That being said, one thing appears beyond dispute: control of the intelligence agency ultimately resided in Langley, Virginia, at the headquarters of the CIA, without whose approval and support the NDS would have ceased to function.

Ahmad Zia Saraj, the NDS’s last acting director, had to be approved by US intelligence before being considered for the position. “That was only allowed with the CIA’s okay. Otherwise, it would never have been possible,” an Afghan security analyst told me on the condition of anonymity. The nature of this relationship was established in practice as soon as NATO troops invaded back in 2001. “Company men” such as Greg Vogle, a close associate of Hamid Karzai and former chief of the CIA’s station in Kabul, insisted on expanding the agency’s shadowy structures in Afghanistan in order to search for terrorists. To this end, recruits were solicited from two groups above all: former employees of the Northern Alliance and ex-KHAD officials, the Kabul-based intelligence agency built by the KGB in the 1980s.

To some, it might seem paradoxical that Washington would enter into this de facto alliance with former enemies, for during the Cold War, the KHAD had targeted the mujahideen rebels whom the United States and its allies supported. Most of the victims of this infamous intelligence agency were civilians, and its war crimes have still yet to be genuinely confronted. Similar to the case of Syrian intelligence officials who have fled to Europe in recent years, a number of KHAD war criminals can be found in Germany and the Netherlands today. After the fall of the Communist regime in Kabul, both countries became popular destinations among Afghans who had been members of the PDPA and served in the regime’s military or intelligence apparatus. While the KHAD’s victims continue to process their trauma and search for the hastily buried remains of relatives it once kidnapped and murdered, several of the agency’s former figureheads have made a comeback of sorts thanks to the War on Terror. War criminals such as Mohammad Najibullah, the last Communist dictator of Afghanistan and probably the most notorious KHAD director, are now celebrated as heroes, their terror regime relativized and romanticized. For its own part, the CIA relied on the one-time KGB apprentices, whom it viewed as suitable and well-trained intelligence agency material. In contrast, the recruits from the Northern Alliance milieu appeared less professional, which is why many were sent to the US to receive training. The most notorious example is Amrullah Saleh, Afghanistan’s last serving vice President.

In the early years of the Karzai era, Saleh climbed the ladder to become the head of NDS. Since then, he has been accused of committing numerous war crimes by various human rights organizations. NDS prisons were among the most brutal outgrowths of the War on Terror.

They were places where even the most unimaginable torture methods were used regularly. In Afghans such as Saleh, the Americans found just the people to do their dirty work. Saleh’s predecessor, Muhammad Arif Sarwari, was similarly infamous. Sarwari, who immediately assumed the post of NDS director after the fall of the Taliban, was once a key figure in the intelligence agency of the mujahideen leader Ahmad Shah Massoud. Once the mujahideen captured Kabul in the 1990s, Sarwari took over the KHAD and began a collaboration with the Communist intelligence officials in Kabul. This same alliance was resurrected by the War on Terror. For example, one NDS director was the famous ex-Communist Masoom Stanekzai, who gained notoriety during the Ghani years for expanding the use of brutal raids that claimed numerous civilian lives. Although growing criticism eventually pressured Stanekzai to resign, he went on to lead the Afghan government’s negotiation team during peace talks with the Taliban.

Over the course of the US occupation, the NDS developed into a mafia-like intelligence network with virtually unlimited resources at its disposal thanks to the CIA. Not only did the crimes of the KHAD go unaddressed, a KHAD 2.0 was created in the form of the NDS, which perfected the KGB’s brutal interrogation methods with the help of the CIA. In spite of the clear hierarchy between the Americans and the Afghans, NDS agents managed time and again to take advantage of their positions. They pursued personal vendettas, unreservedly bombed civilians for ideological reasons, and used the millions of dollars from Washington and Langley to build up personal fiefdoms that they maintained through both terrorism and human and drug trafficking.

One figure who particularly embodied this criminal lifestyle is Asadullah Khalid, Afghanistan’s defense minister towards the end of the occupation. Khaled had previously served as director of the NDS and as governor of various provinces. Several international human rights organizations attest that in all of the positions he held, he committed grievous human rights abuses including torture, sexual abuse, and murder. According to reports, Khaled had personal torture dungeons at his residences in the provinces of Kandahar and Ghazni. He also had young girls kidnapped and held them as sex slaves. According to an in-depth exposé by CBC News, he also ordered the murder of five United Nations workers who had posed a risk to his lucrative drug business. Khaled’s numerous wrongdoings were even discussed in Canada’s parliament in 2009. Ultimately, the Canadian politicians more or less concluded that their country had allied with some highly problematic actors.*

It was obvious that figures such as these were not simply going to disappear overnight. The NDS and the paramilitary units of the CIA are among the bloodiest consequences of the War on Terror in Afghanistan. Though they no longer exist in the same form since the withdrawal of NATO troops and the Taliban’s recapture of state power, their legacy persists in the General Directorate of Intelligence (GDI), the intelligence agency set up by the Taliban. And indeed, their brutality ultimately strengthened the Taliban, as can be seen in the example of Khost Province. For years, large swaths of Khost had been controlled by the so-called Khost Protection Force (KPF), a paramilitary organization founded by the CIA. Notorious for its numerous human rights violations, the KPF routinely kidnapped, tortured, and murdered civilians.**

While conducting research in Khost back in 2017, I had my first personal encounter with the CIA militia. Deliberately not mentioning my work as a journalist, I said I was a visitor from Kabul. Otherwise I might have run into the same fate as the Afghan BBC journalist Ahmad Shah.

In April 2018, Shah was killed by “unknown gunmen,” as several media outlets reported. Yet it was an open secret that the KPF had murdered the journalist after threatening him multiple times. Although local journalists were aware of the KPF’s involvement in the case of Ahmad Shah, they would have endangered both themselves and their families had they reported this information. The militia mainly hunted those journalists and human rights activists who focused on the war crimes it and the Americans committed in the region. For this reason, several colleagues in Khost with whom I have worked in the past have explicitly requested I not publish their names.*** The terror regime of the KPF fomented extremism in the region for years. Many victims of the militia have now joined the Taliban, making Khost a particularly apt illustration of the myopia of the American counterterrorism struggle. “As soon as their high pay dries up, they are going to pillage this city,” a merchant from the province told me during my research.

“The Legacy of the CIA” is an exclusive excerpt from Graveyard Empire, published by special arrangement with Interlink Books.

* CBC News, “Afghan governor’s rights abuses known in ’07,” April 12, 2010.

** Emran Feroz, “Atrocities Pile Up for CIA-Backed Afghan Paramilitary Forces,” November 16 2020.

*** BBC, “BBC reporter Ahmad Shah killed in Afghanistan attack,” April 30, 2018.