Breaking stereotypes that their country is only about war, members of a group of Afghan women continue to write despite the Taliban.

Lillie Razvi

In 2019 Maryam Mahjoba’s sister noticed an open call from a social enterprise in the UK called Untold Narratives, inviting Afghan women writers to submit short pieces of fiction. It read, “You don’t need to be an experienced writer, you just need to have a story to tell.” The stories could be submitted in Pashto or Dari and would be considered for a pilot project to connect Afghan women writers with international literary editors and translators. Maryam lacked confidence in her writing abilities, so her sister decided to submit one of her stories on her behalf.

Maryam had kept a diary ever since she was a young girl. As a child everything in her life had been about war, but in writing she had found herself. She studied law at university but due to muscular dystrophy she became increasingly wheelchair bound and so, unable to work. She spends much of her time at home, reading, listening to music and writing in her diary. She lives with her family, who all support her writing apart from her father.

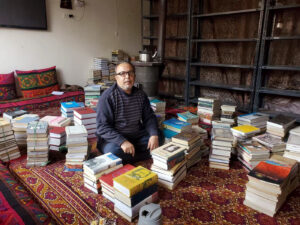

Two years earlier, Lucy Hannah, founder of Untold Narratives, was working in Afghanistan with women scriptwriters on the country’s long-running radio soap opera New Home, New Life. The writers shared their frustrations about finding a publisher for their prose fiction and the challenges of developing a readership for their writing. One had published short stories online, but said: “I’ve never come across a local publisher willing to publish a book without asking for money from the author. And it’s impossible to find a foreign publisher who wants to read books about anything except the war.”

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Afghanistan has been mired by ever-changing rulers, invasions, revolutions, and wars. This uncertain political backdrop has meant the establishment of a stable, local creative infrastructure has often been disrupted. Although Kabul had many publishers at one time, there has always been a dearth of experienced editors and literary translators. The situation is particularly difficult for women. Even in Kabul, places for women to connect with other writers to share their creative work is limited and it is a challenge to find a publisher for their stories locally, in their own languages, never mind globally in translation.

Untold Narratives was established as a response to this need — a writer development program for writers marginalized by conflict or community. Its launch project was Write Afghanistan — a scheme for Afghan women writers to collaborate with international editors and translators in two of their local languages. It was clear the radio scriptwriters were not alone in their struggle and desire to get their work published — more than 200 submissions were received in response to the first open call for women writers across Afghanistan. Many were handwritten and sent via mobile phone or from internet cafés. Maryam’s piece was among them.

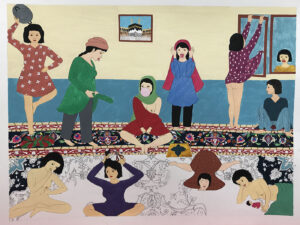

The stories explored domesticity, women’s social and political rights and touched on universal themes of family, friendship, love, and betrayal. All fiction, many were inspired by real life and others were a modern take on Afghan folk tales. The submissions were reviewed by a team of experienced Afghan readers and translators, and with a second open call a year later, a group of 25 Afghan women writers joined the Write Afghanistan program.

Along with Maryam the group included a doctor, two scriptwriters, four teachers, a lawyer, a psychologist, a factory worker, an engineer, NGO workers and university students. From 22 to 61 years old, some were just starting their studies at university, others, matriarchs raising grandchildren. The majority lived in metropolitan areas such as Kabul and Mazar-e-Sharif, but others came from more remote provinces. Most of them had never met but they were unified by their desire to write.

Internet connection was unreliable so Untold organized for the writers to meet regularly with their international editor and translator via WhatsApp. Group workshops and one-to-one calls were held across three time zones — the writers in Afghanistan, one of their editors in Sri Lanka and translators in London. They wrote drafts in their first language, Pashto or Dari, each successive draft was then translated into English for the editors, before the next editorial call where feedback was interpreted, and the writers would then re-write. They also used the connection to exchange ideas, experiences, and techniques. Maryam Mahjoba had never worked with an editor or rewritten any of her stories before.

Despite the pandemic, the editorial process continued and although power failed, and internet connections would often cut out, Mahjoba developed her original story, “Turn This Air Conditioner On, Sir” and wrote another, “Companion,” a poignant portrait of a grandmother who is feeling lonely because her children have emigrated.

“Turn This Air Conditioner On, Sir” was her first piece to be published in English appearing in Words Without Borders in 2020. She then went on to have her work published in German, having been selected as one of three writers by Untold’s German partner Weiter Schreiben to participate in a literary letter exchange. Through this project Mahjoba was paired with established author, critic and translator Ilma Rakusa, and their respective lives and experiences were exchanged and published in German in Weiter Schreiben’s online literary journal. Mahjoba was also commissioned to write a piece for the German newspaper Der Spiegel.

In August 2021, the writer’s group was upended. The Taliban swept across the country and Kabul fell. Many Afghans attempted to flee their country. At the time, the writers, including Mahjoba, were busy refining their stories for an anthology of their short stories to be published in the UK by MacLehose Press. They were adamant they wanted to continue with the anthology despite the risks.

While many of the writers began difficult journeys out of the country as refugees, others were unable to or chose not to leave. Mahjoba had been trying to leave for three years prior, for medical care, but now her chances were even more limited. Others in the group found refuge in countries including Tajikistan, Iran, Italy, Sweden, the US, Canada, and Australia. In February 2022 the anthology My Pen Is the Wing of a Bird: New Fiction by Afghan Women, the first of its kind in translation, was published by MacLehose Press. The anthology opens with Maryam’s story, “Companion” and concludes with “Turn This Air Conditioner On, Sir.” As of 2023, the book has also been published in the US, Japan, Korea and Ukraine, and sold more than 13,000 copies in English; it was also shortlisted for the 2022 Jan Michalski Prize for World Literature.

With the support of KFW Stiftung the group has grown to become Paranda Network, working with Afghan writers at home and in the diaspora. Writers, translators and editors come together virtually across borders and time zones to create and hone new fiction, share ideas and secure commissions, in translation. Friendships have developed between some of the writers, and they continue to provide each other with support and advice.

“Kabul’s Haikus” by Maryam Mahjoba was developed through the Paranda Network, where she and her fellow writers remain determined to bring their stories to readers in other parts of the world. Despite living under the Taliban’s oppressive regime and the upheaval and trauma of fleeing their homes, they pick up their pens and continue to write.

What indomitable women. Can’t wait to read their stories

Incredible story, in my experiences of having a dialogue with the Afghan Women – they are the most resilient, sensitive and innovative souls.

Oui, les femmes Afghanes sont merveilleuses et résilientes. Je suis auteur et je viens de terminer une fiction: je suis Français mais totalement touché par cet ostracisme et révolté par l’attitude des démocraties et du monde musulman : tous sont unanimes pour condamner l’éradication des femmes et créer la famine organisée. Ma démarche est iconoclaste et pourrait surprendre. Votre site est très utile et révélateur de bien des non-dits.