A Moroccan prison where many were at one time secretly held.

Rana Asfour

In 1966, when Tahar Ben Jelloun was not yet twenty, two officers stormed into his family home to serve insults, a third-class train ticket and a summons to present himself before the Commandant at the El Hajeb army training camp near Meknes. The previous year, Tahar had participated in a peaceful student demonstration calling against “injustice, repression and a lack of freedom”—a dangerous action in a Morocco under the rule of Hassan II where grievance against the regime, the king, and his henchmen was met with bloody repression and “young men disappearing.” With the summons and very little specific information, since Morocco had no institution of military service, Tahar’s own punishment for his generation’s “idealism and naïveté” had begun with no foreseeable end in sight.

The Punishment, translated from the French by Linda Coverdale, is a first-person account from an author who considers writers to be “witnesses of history.” It has taken him fifty years to “find the words” for his eighteen-month ordeal, relying on a memory that has proved “extraordinarily faithful and brought back everything that happened.” This is the account of a place where “sophisticated brutality” was meted out to make men out of boys, and where prisoners were held with no trial by people in power who would rather turn them into heroes fallen “for the fatherland with medals when they’re dead,” rather than risk releasing them to tell their stories to the world. A doctrine, the author writes, not exclusive to Morocco; in Egypt, for instance, Nasser was sending his Marxist opponents into the desert, handing them over to psychopaths for maltreatment.

This is not the first narrative that Tahar Ben Jelloun has devoted to the period of social and political turmoil known as the “Years of Lead” under King Hassan II’s rule, which extended from the late 1960s to the late 1980s. The Moroccan-French winner of the 1987 Prix Goncourt and the 1994 Prix Maghreb is a novelist, poet and essayist who has visited this hallowed ground before, in novels such as Corruption and This Blinding Absence of Light (2001)—a deeply moving and gut wrenching tale, also translated from the French by Linda Coverdale, inspired by the testimony of a former inmate at Tazmamart, where political prisoners were left to wallow in cells less than ten feet long and only half as wide, in which it was impossible to stand up. Details of this prison “designed specifically to torture inmates to death” appear in The Punishment tucked in the translator’s note at the end of the book.

The secret prison, off in the Atlas Mountains of southeastern Morocco, was built after the failed 1971 Skhirat attack on the king. Of the fifty-eight indicted cadets to enter its tomb-like confines, only twenty-eight would survive and only years later would a smuggled note tell the world of their existence. In 1991, succumbing to international pressure, Hassan II finally closed it down, releasing all its prisoners and approving a reparations program for the families of the disappeared. Since his death in 1999, his son King Mohammed VI has been determined to break away from his father’s legacy, initiating reforms in a country that remains the only Arab constitutional monarchy in Africa. As late as last year, however, Amnesty International continued to monitor rights in Morocco closely, noting that, “The authorities harassed journalists, bloggers, artists and activists for expressing their views peacefully, sentencing at least five to prison terms for ‘insulting’ public officials and apparently targeting others with spyware.”

Tahar Ben Jelloun early in his writing career (Photo: unknown)

In The Punishment, Tahar Ben Jelloun reveals how three years after his release from detention and through what he can only describe as intervention of “God or Chance, God or Destiny” did he escape from a “surprise” plot to rope him into the Skhirat coup d’état by its two masterminds, and El Hajeb jailers and torturers: the Commandant, Ababou, and his henchman and second in command, Chief Warrant Officer Akka, who is best described by his superior as an officer who “knows only force, blows, barbarity that would reduce anyone at all to the level of an animal.” Following a chance encounter, Tahar decides he can no longer remain in Morocco and books a plane ticket to France, where he continues to live and write today.

From the moment in The Punishment that Tahar boards the train to Meknes, it dawns on him that his life as he’s known it has ended. As the “landscapes drift by with a strange indolence,” he mulls over the unfair treatment, his powerlessness and “all that His Majesty’s police were about to put a brutal and definitive end to,” beginning with the loss of Zayna, his fiancée, with whom he’d fallen in love the second they’d both reached for the same copy of Albert Camus’s The Stranger. Ironically, Mersault the protagonist in The Stranger suffers Tahar’s predicament when he is charged with murder and like him, is stripped of agency as his fate falls into the hands of others.

Tahar’s last night of freedom in a rundown motel in Meknes is a farcical shedding of comforts as reality begins its descent into a surreal hell; he notes the motel’s owner who is unshaven, blind in one eye with a tic who admonishes that no whores are allowed as he administers him and his brother (who’s insisted on accompanying him until the barrack gates) with a large key to a room with two bug-infested beds and dirty sheets randomly stained with blood. His brother produces a roast chicken he pulls out of his bag with two oranges and Laughing Cow cheese. At night the brothers launch a futile battle against the bugs and mosquitos that have invaded their room before succumbing to hysterical laughter followed by restless sleep. The village itself proves to be no better in the light of day as it wakes up to its beggars, its bees and flies and “lost tourists pestered by a swarm of fake guides.”

By noon, Tahar is in solitary confinement and his world is officially “topsy-turvy.”

With his head shorn “like a sheep condemned to death” on his first day, Tahar already feels “stunted, crushed: a bedbug, a plaything for louts.” Known now as serial number 10 366, he calls upon his literary memory of books and films to fill him with energy and the desire not to get himself killed by the “program of abuse and humiliation.” He recites passages from Dostoyevsky, Chekov, Kafka and Victor Hugo as scenes from Charlie Chaplin stream through his mind. He ceases all thought, all reasoning as he feels himself slip further and further into “the territory of the absurd”—a place stripped of creativity and imagination, surrounded by nothing but hatred and inhumanity meted out by psychotic officers formerly trained in the French army, proud of their stupidity and brutality.

The rotten food and punishing heat eventually take their toll on Tahar. When he is admitted to Mohammad V Hospital for treatment, he seizes the chance to ask for paper and a pencil and jots down the first of his compositions on the hospital’s prescription forms which, unbeknownst to him, will launch his literary career when after his release they are published in poet Abdullatif Laãbi’s poetry review Souffles (see Olivia Harrison and Teresa Villa-Ignacio’s Souffles-Anfas, A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics from Stanford University Press).

Two weeks later he is back at the barracks where detainees continue to die in sham military maneuvers and from escalating punishment. He continues to furiously compose verses in his head that he jots down as soon as he manages to secure some paper. He hides them in the sewed-up pockets of his fatigues.

During his incarceration, Tahar serves time in two camps, both of which are run by an army that fostered “a deep racism between those of the south, the Amazigh and those of the north, the Rif; between the people of the cities and those of the countryside, between those who can read and write and those who jabber in anger.” Despite that, he incredibly writes, “I could have come out of the camp changed, hardened, an adept at force and violence, but I left as I had arrived, full of illusions and tenderness for humanity. I know that I am mistaken. But without that ordeal and those injustices I would never have written anything.”

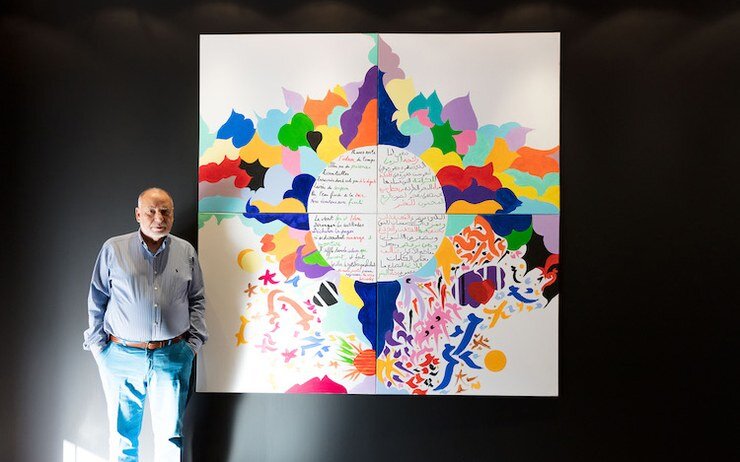

Tahar Ben Jelloun with his quadriptych, displayed at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris.

Tahar Ben Jelloun, the Moroccan-French novelist, poet and painter was born December 15, 1947 in Fez. He started drawing even before writing, however he began painting only later in life. After attending a bilingual French-Moroccan primary school, he studied at the French lycée in Tangier until he was 18. He then went to the university Mohammed V in Rabat where he majored in philosophy and wrote his first poems collected in Hommes sous linceul de silence (1971). He later taught philosophy in Morocco. However, in 1971, following the Arabization of philosophy teaching, he had to leave for France, as he was not trained for pedagogy in Arabic. He moved to Paris to pursue studies in psychology. From 1972 onwards, he has written for the daily newspaper Le Monde. Writing in French, he published his first novel Harouda in 1973. In 1975 he earned a PhD in social psychiatry. His writing often reflects his experience as a psychotherapist (La Réclusion solitaire or Solitary, 1976). In 1985 he published the novel The Sand Child which made him famous. He was awarded the Prix Goncourt in 1987 for Sacred Night, a sequel to The Sand Child. In addition to his many novels, Ben Jelloun has authored several educational publications including Racism Explained to My Daughter and Islam Explained to Children. In 2008 Tahar Ben Jelloun was elected a member of the Académie Goncourt. He is the most translated French-language author of modern times. He has been nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature.