A national cultural phenom with his French pop band Zebda, the Franco-Algerian former singer-songwriter Magyd Cherfi discusses his career as a writer, his life as a primary source of inspiration and the release of his first novel, following the success of a three-part autobiography.

Sarah Naili

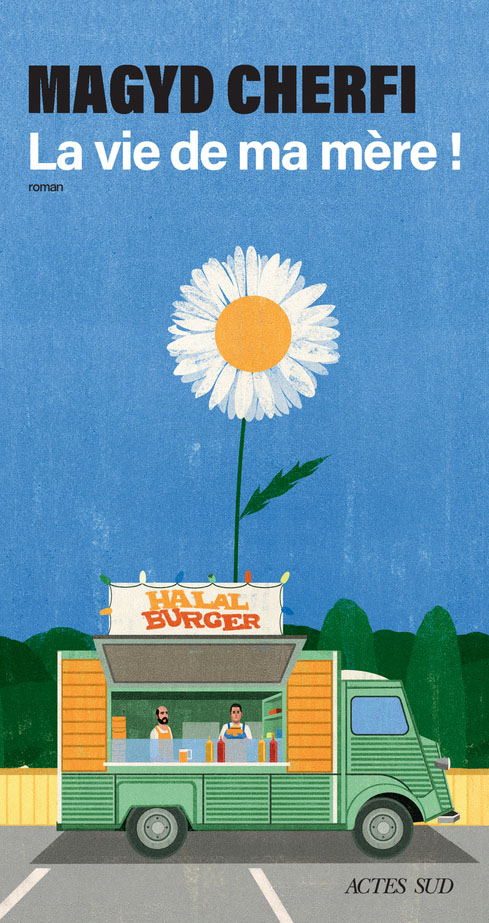

We met up with Magyd Cherfi in Montpellier, who was in town for the release of his first novel La vie de ma mère!, published by Actes Sud. This was an opportunity to look back at his career since the meteoric years with Zebda (the Toulouse-based music group), his community activism and his literary influences, and to question the construction of an identity when you’re born in France into a Kabyle family. His landmark autobiography, Ma part de Gaulois, was adapted for the cinema earlier this year.

Sarah Naili: You’re of Kabyle origin, and you’re a second-generation immigrant. The theme of the construction of identity can be found in your work: from your first book, Livret de famille, and then the revelation of Ma part de Gaulois. Then La part du Sarrasin. And already there, we see a distancing through the choice of the personal pronoun between Ma part de gaulois and then La part du sarrasin. And now, with your first novel, La vie de ma mère! in which Slimane the narrator questions his heritage, traditions and family. Slimane tries to strike a subtle, fragile balance:

I was looking for a bridging identity, a first name that had no Arabic connotations without being devoid of them.

Would that sum up your identity journey?

Magyd Cherfi: Yes, I think so. There’s this confusion about who you belong to, what people you belong to, what history you belong to. I’m the son of Algerian parents, illiterate people from the mountains, with no memory of their own history, and others who were born in what was called French Algeria. So, we told them you were French, but we didn’t consider them as such. And both my grandfather and my father were never treated as French. Thus, I was born in France and all I remember is being French. At school, very quickly for example, we were told your ancestors were the Gauls and I think I liked that and so did my friends. All of a sudden, we were given branches to hold on to. We belonged to a history. Well, that was 2000 years ago, they were blond, and the whole legend of this history of France mystified by the French school of heroes like Charlemagne, Clovis. And then the succession of all those Capetian, Carolingian and Merovingian kings. And we followed this French trail which, we thought, went all the way back to us. And then, as the years go by, we realize that we don’t belong to these people who wanted to tie us to them. On the other hand, at school, you had to be French, but after 5 p.m. you were still the sons of natives, Arabs, bougnoules [1].

My mother, 80 years on, still worries about being expelled! The Republic didn’t make her feel at home, so she spent her whole life in terror, as did my father, because we could be expelled at any moment. And my whole “Francophonie” dissolved, because I said to myself, you can’t treat people so badly and expect them to pledge allegiance to what they call the Republic. The Republic is my parents’ worst enemy and of all North Africans and black Africans, because we’ve become a threat as time goes by.

The big day for us sons of immigrants was the victory of the left, because in the ‘80s, I think 100% of North Africans leaned left. And so we were a new army ready to wear and defend the progressive colors of the left until we demonstrated with the March of the Beurs, known as the March of Equality. We came to demand equal rights. And then the left in power offered us a 10-year residence permit, which they saw as a panacea. Look how generous we are, how we welcome you. In fact, it was the opposite, since we went from equal rights to a residence permit, a reprieve which is in fact a ten-year time-limit to check whether the Arab melts into the Republic’s pot. Because there was this sort of mistrust and suspicion towards us. Over the coming decades, we would be subjected to a wide variety of tests. These will tell you if you’re French enough. There was a hope that was born in childhood, we believed in it and then it faded a little as we went along.

SN: I know you’re a big fan of French literature: Sartre, Flaubert, Voltaire, Rousseau. Did you feel the urge to turn to authors from the East and the Arab world, to connect with other intellectuals, other literary traditions?

MC: Of course, in this instability, there are these movements of being more French than we should be, or being less French, since we’re not. And this permanent movement of refusal or acceptance, there have been times when I’ve felt too French and other times not French enough. And so after the natural passion for literature of the 19th century, I turned to Tahar Ben Jelloun and to the discovery of Egyptian, Moroccan, Tunisian authors to rediscover an intellectual family and universalist, feminist, anti-racist, progressive spirits.

SN: And today, how would you define your relationship with the Arab world? Are there countries you’d like to go to?

MC: Not really, because I often go to Algeria, since that’s where my parents from little Kabylia come from, and I’ve found obscure, obscurantist things there. I go there for the scent of fig trees, perhaps. I go there for the illusion of a magical origin. I go there for a language I understand a little, but which has been lost along the way. You go there for a certain number of things that are of the order of magic, and for a while you forget the things that make the world progress.

SN: Being exiled from one’s homeland somehow implies maintaining a nostalgia, a myth of the country of origin; a desire to crystallize it into a tangible memory. Don’t you think that the dance between modernity and tradition in France is ultimately the fate of all young people in Arab countries?

MC: I turned 20 40 years ago, and at 20, I was expecting young people in the Arab and Muslim world to rise up as a spontaneous generation, progressive, feminist, leftist, I was going to say carrying humanist values. And there have been tremors. For 40 years, I’ve seen tremors, but authoritarian states have prevented these things from happening. And today I’m at an age where we despair of ever seeing this renewal. Even if I know that there are advances, for me they are far too meager, far too slow.

SN: In your Toulouse neighborhood, you were involved in community life from an early age. The Tactikollectif association, which still exists today, offers tutoring and support for artistic and civic expression. Do you still follow these associations to some extent?

MC: Over time, I abandoned the field, feeling a little disillusioned. I got carried away by the music, and with my friends we moved away from the neighborhoods and their daily lives, almost away from our families. We were on tour, we were out of touch with working-class realities. And then, perhaps as I got older, I grew closer to them, from a distance, through occasional interventions. But I don’t want to relive the misery I experienced because it tortures me too much. I go into the neighborhoods, I still go a little, but it’s painful to see the state these working-class neighborhoods are in.

SN: So the mother, the archetypal mother, is a muse for you? We see this already in your songs such as “Inchallah peut être” and “pleurer sa mère.“

MC: Yes, yes. Today, my mom’s life, yes. Yes, yes, because in the end it’s an inspiration to talk about her. For me, it’s about the immensity of exile, the immensity of immigrants, the immensity of North African Muslims. She represents a bit of everything, because she represents what can be modern for a person who comes down from the mountains and doesn’t know how to read or write, or where she comes from, or who she is, or even if she knows she’s a woman. On the other hand, you have to be a scholar. You have to be hooked on knowledge, and knowledge has landed us on the moon, by the magic of this intellectual mechanism that makes you doubt everything. And so, she represented these two sides, a side of knowledge, with doubts about the hereafter, and a side where you can’t live outside the norms of Islam. And she carried this contradiction with her, so she infused us with schizophrenia. Belonging to one’s own kind and belonging to the light are two appalling things.

She had an obsession with academic success and organized a secret army of nuns around us to help our moms, from the local priest for tutoring, social workers for math, educators and an armada of social workers and white adults who swirled around the house. And with mothers, shall we say, distant knowledge. So, she said:

—”I am your mother.”

And I replied:

—”Yes, you’ve been my mother, but today we need to have a relationship of equals.”

—”There are no equals since I am your mother.”

So knowledge led us to think as equals. Knowledge took us away from Mom, and trench warfare began.

SN: I wanted to return to a very nice passage of Slimane’s, when he met this old literate Tunisian gentleman. Is an Arab intellectual an oxymoron for Slimane at that point?

MC: For the hero of our world, yes, because as an old Maghrebi, he only knows uneducated people, his uncles, his neighbors. And besides, you only have to visit the working-class neighborhoods to see that all these old men are people who can’t read or write very little, and who gabble French more than they speak it. My parents remember seven years of the Algerian war, from 1954 to 1962. That’s our history, and before that? A precipice.

At school, we are offered 2,000 years of French history. That’s where the French got it wrong, thinking we were the bearers of a double culture. But as the sons of immigrants born in France, we’re left with crumbs of our original culture. And we have the educational immensity of the kings of the Age of Enlightenment all to ourselves. And so, yes, it’s still a shock to find erudite old Arabs, because it’s not part of everyday life. Basically, it’s good for our parents, and it’s a terrible failure on the part of the Republic with regard to the children of immigrants who haven’t been lucky enough to have access to the codes. That’s what I mean. And so the hero’s amazement at a guy who conjugates the verb perfectly. And even today, I can still be astonished. Because it’s not in our habit to come across elevated things in negritude. That’s not to say, of course, that it doesn’t exist, but it’s in the privileged circuits where, even in Morocco, I’ve been surprised to find elites outside the soil. I’ve seen students who hardly spoke any Arabic at all, who were hyper Anglophone and Francophone. And sometimes when we go out into the country, we’re taken for zombies. But it’s possible to live in bubbles where language itself is almost deliberately expelled because it’s useless to a form of modernity.

[1] A racial slur akin to “camel jockey.”