Select Other Languages French.

Writer Mai Al-Nakib reviews the recent reissue of Salman Abu Sitta’s evocative memoir, Mapping My Return, the only memoir in English by a Palestinian Arab who grew up in the Beersheba district prior to 1948, published by AUC Press.

Mapping My Return: A Palestinian Memoir, by Salman Abu Sitta

AUC Press 2025

ISBN 9781649034359

Maps have always been magical to me. Miniaturized, diagrammatic representations of masses of physical geography. A neatly folded rectangle tucked in a pocket or purse, marking one’s current place in the world, one’s future orientation, and, if required, guaranteeing one’s way home. For someone cursed with an unreliable sense of direction, maps have often brought comfort and, when lost in an unfamiliar city in the dead of night, facilitated safe passage.

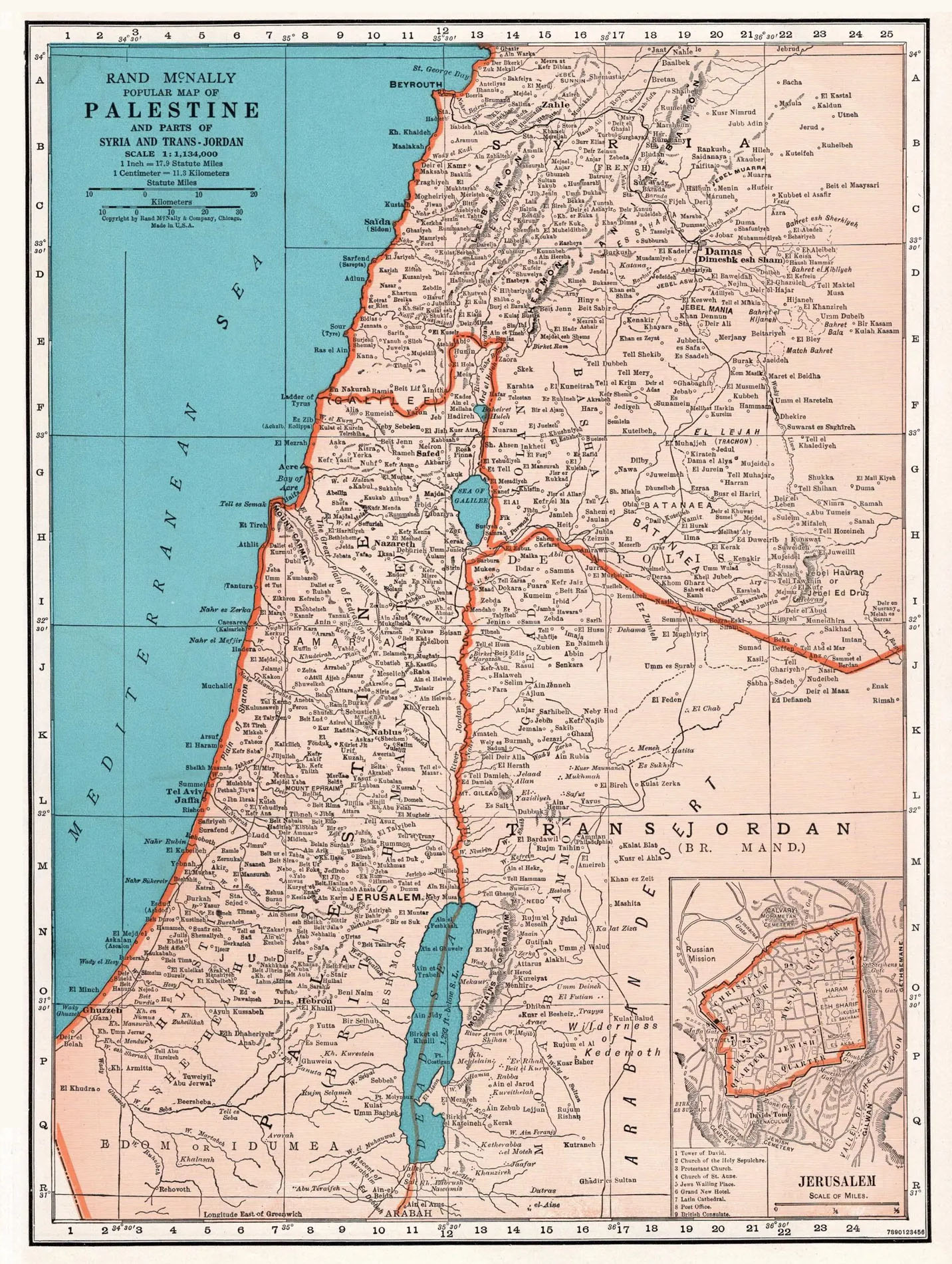

But maps — as Salman Abu Sitta, author of Mapping My Return: A Palestinian Memoir, well recognizes — are more than mere markers of place or neutral facts we consult to confirm or correct our location in the world. Maps are also narratives of the past, present, and future. They are powerful chronicles of presence and absence, ownership and theft, truth and lies. Under European colonial conquest, maps were records of land grabs used to legitimate title; the extraction of resources; and the expulsion or erasure of Indigenous inhabitants. Edward Said identifies Napoleon I’s massive publication, Description de l’Égypte — produced by an army of scholars who accompanied him during his military expedition to Egypt in the late eighteenth century — as pivotal in this regard. “Yet,” as he writes in Culture and Imperialism, “most cultural historians, and certainly all literary scholars, have failed to remark the geographical notation, the theoretical mappings and charting of territory that underlies Western fiction, historical writing, and philosophical discourse of the time” [original emphasis]. The significance of geographical notation, theoretical mappings and charting of territory to claims of European superiority and, thus, their ostensibly righteous possession of that territory have also been elided, Said iterates. It is against this purposeful lapse that Abu Sitta’s provocative, engaging memoir strives — and with great success.

Mapping My Return, first published in 2016 by The American University in Cairo Press, has been reissued this year with a new Afterword by the author. The memoir aims, first, to “[tell] the story of the long journey of a refugee trying to return home” and, second, “to try to put a face to [the] invisible enemy,” who ran him and his family out of that ancestral home in May 1948, when he was ten years old. There is a third, intransigent aim of this memoir: that is, for it to “serve as a road map to the return to our homeland.” This third goal is not idealistic rhetoric. Abu Sitta is a highly accomplished engineer, and it is with an engineer’s structural precision and keen foresight that he is able to come up with a viable plan of return. Reading this plan, even against the ongoing, unceasing horrors of genocide in Gaza and ethnic cleansing in the West Bank, one cannot help but be convinced that Abu Sitta’s imaginative cartography can and will materialize. For this reason alone, his timely memoir is indispensable.

Salman Abu Sitta was born in December 1937 in his beloved al-Ma‘in, where eleven generations of the illustrious Abu Sitta family cultivated over six thousand hectares of their fertile land. The exact date of his birth was not recorded, but he was “always told that it was at the time of the general strike, or the Arab Revolt,” setting him up for a life of resistance. This memoir is, in many ways, as much a memoir of al-Ma‘in and the Abu Sitta family as it is of Salman himself.

The first chapter — preceded by a 1945-48 map of Palestine and then a 1948-50 map of al-Ma‘in — is titled “The Source (al-Ma‘in),” and in it, we learn all about the idyllic world into which young Salman was born. Apart from the farmland used by his family to cultivate wheat, barley, and maize, his father also planted figs, grapes, almonds, and apricots in the karm, or orchard, beside their family home. In addition, they owned — among other properties in Palestine and Egypt — a bayyara, or citrus grove, in Deir al-Balah, close to the sea, built by his great-grandfather Saqr in 1844, where the family would visit during the summer. He describes, in meticulous detail, the landscape of al-Ma‘in in its lush, springtime glory. The surrounding meadows become “a carpet of green,” overlaid with “crimson anemones, scarlet poppies, yellow daisies, and yellow-and-white chrysanthemums.” The sky is full of birds: “sparrows, larks, starlings, bulbuls, and storks,” and his favorite, “the qerqizan, with its long blue tail and its majestic walk.” He describes the wind rustling through their wheat and barley — far more than was required to feed al-Ma‘in’s inhabitants, the surplus sold to the British for a hefty profit. Young Salman pays attention to the cows and their sweet milk; the noble horses and herds of sheep; the red and yellow melons; the cactus fruit from the cactus fence surrounding his father’s karm. There is a flour mill; a diesel-operated pump and a ninety-five-meter well; huge barns and large sheds; and the all-important school established by his father in 1920. He recounts the pace of an ordinary day in al-Ma‘in, providing the names of individuals who worked the land and owned shops in the center. He remembers the lovely embroidered thobes worn by the women; dancing during Samer, the harvest festival; horse races where eager boys competed for the attention of eligible girls. Abu Sitta vividly conveys a sense of belonging and situatedness in al-Ma‘in, of growing up with the comforting freedom of being a child with the history of generations at his back and the promise of better things ahead.

Specifics matter. Abu Sitta’s are not just any flowers or fruits, not just any lands or farmhands. Names matter because Abu Sitta is not only attempting to evoke a distant past in narrative, but also to definitively reclaim the landscape upon which that past unfolded. By way of precise naming, he is also refuting the false claims, myths, and purposive demolitions and erasures of Palestinian villages, properties, and presence by the conquering Zionists. He does this by utilizing not only local and colonial documents throughout, but with his own memory and the memories of those he knows personally. The specificity of such memories legitimates his reclamation by constructing a map of what once was and simultaneously acting as a blueprint of what can and will be again. However, this memoir does not read as a nostalgic eulogy for a lost paradise (brutal and violent as that loss was, as Abu Sitta describes in equally specific detail in subsequent chapters), but rather as an exuberant and confident celebration of rightful ownership. There is no ambiguity to whom al-Ma‘in belongs. As he states:

I never imagined that I would not see these places again, that I would never be able to return to my birthplace. The events of those two days [when al-Ma‘in was captured by the Zionists] catapulted us into the unknown. I spent the rest of my life on a long, winding journey of return, a journey that has taken me to dozens of countries over decades of travel, and turned my black hair to silver. But like a boomerang, I knew the end destination, and that the only way to it was the road of return I had decided to take.

The personal story of Abu Sitta’s dispossession, living in the shatat — “dispersion in exile” — is primarily relayed chronologically. But since the private life of this individual, like all Palestinians, cannot be extricated from the land and history of Palestine itself, he seamlessly weaves in temporal returns that provide necessary background and context. This does not disrupt the flow or intimacy of the personal narrative. On the contrary, it manages to bring history to life through his genealogy, or nasab, in addition to the lives, actions, and deaths of members of his immediate family, who fought in 1914 against the British; then during the Arab Revolt; then again in 1948 against the theft of their land by the Zionists; and in subsequent years resisting occupation. Abu Sitta traces the histories of members of his clan along with numerous other Palestinians through foundation stones and ruins; wells and the landscape; the Royal Geographical Society map room and other libraries and bookstores around the world; journal and newspaper articles, travel accounts, and historical texts of all kinds; letters, testimonials, interviews; family lore told around the shigg, or hearth, along with personal memory. Abu Sitta is a tenacious researcher, following every clue, leaving no stone unturned, but the expression of that extensive research — like the best fiction — is lively and engaging, a compelling read.

Like so many Palestinians, Abu Sitta’s story is defined by movement: from al-Ma‘in to Cairo to Kuwait to London to Ontario, then back again to Kuwait, where he remains today, plotting his boomerang return back to Palestine. Despite immeasurable loss and trauma, Abu Sitta’s is a tale of determination, hard work, and success. He is a brilliant student, graduating top of his class, earning the highest degrees, excelling both at work and in academia wherever he lands. He raises two daughters with his beloved wife. He makes friends all over the world to whom he remains loyal. And through it all, he continues his political efforts for Palestine, unwavering with regards to the right of Palestinians to return home.

One of the most moving chapters in Abu Sitta’s memoir recounts his two-week visit to Palestine in 1995, accompanied by his daughter Rania. “I decided to visit my homeland and see for myself the land I knew and had charted over all these years. How does it look now? After spending years poring over its maps, I wondered if I would recognize it. What would be my reaction when I saw the same land I knew, but with strange faces and languages in our streets?” They travel with a hired Palestinian driver, who speaks Hebrew, from Jerusalem to Nablus, Jenin, Tiberias, Safad, the fields of Galilee, Nazareth, Acre, Haifa, Jaffa, al-Ma‘in, Gaza, and numerous demolished villages in between, which he points out to his daughter as the sites of massacres or battles. In Haifa, home of his wife’s family, who owned many properties there and in nearby coastal villages, they locate her family residence with the help of a small photograph of his wife, aged two, sitting on its stone staircase.

The building is now an audit office occupied by foreigners. Abu Sitta and his daughter are given permission to enter their stolen property, and he imagines the life it once contained: “We saw the high ceiling, the wonderful ornamental tiles. The air was filled with memories. Just adding a few old-style sofas, a table with a Turkish cup of coffee, you could imagine my wife’s Aunt Mariam emerging from another room to greet us. I remember her, tall and very beautiful. They called her ‘the Pasha’s daughter.’” Rania is overwhelmed and in tears. One of the auditors tells her: “‘You will be pleased. This house is on the preserved buildings list. It will be treated with extreme care.’” Included in the memoir is that photo of Rania’s mother as a child sitting on the stone staircase with her uncle and, beside it, one of Rania — rightful owner of this cared-for-but-nonetheless-still-stolen building — sitting on that same staircase, her father by her side. One day — everything in this memoir asserts — Rania will reclaim her home physically as Abu Sitta has already done narratively.

In al-Ma‘in, the old cactus fence remains stubbornly in place, though the karm and all its fruit-bearing trees are gone. “‘This is my land, this is my home, this is my birthplace, this is my being, this is my identity that I carried with me everywhere. This will be my final resting place.’” Abu Sitta kneels on the ground and kisses his land — forever his, no matter how many decades pass, no matter how many kibbutzim attempt to colonize it. In what was once the yard of the school built by his father, the first in Beersheba district, only the “faithful eucalyptus tree” remains standing. “I remember playing around it,” Abu Sitta reminisces, “climbing it, and getting scratched knees. During recess, it was the center of our activity. Now its branches were bare. It looked forlorn and abandoned.” He takes with him “two handfuls of the good earth that fed us, witnessed our birth, and after a long life, becomes our eternal shelter.” On this last point Abu Sitta never falters, and, once again, we believe him. He will return.

How he sets out to accomplish this feat is what transforms this personal narrative from conventional memoir to audacious plan of action. In addition to being an able engineer, Abu Sitta is a masterful cartographer, gifted academic, and founder and president of the Palestine Land Society, “an independent non-profit scholarly society dedicated towards research and information-gathering on Palestine, the land and its people.” He is the author of numerous atlases: The Atlas of Palestine (1871-1877); The Atlas of Palestine (1917-1966); Atlas of Palestine: Land Theft by the Jewish National Fund; and The Return Journey: A Guide to the Depopulated and Present Palestinian Towns and Villages and Holy Sites. These atlases are massive, meticulously researched tomes, rivaling the heft of Napoleon’s Description. They are evidence-based, historically accurate maps that, in their specificity and sheer size, are impossible to ignore or dispute. Although each atlas in its way gives the lie to the many Zionist fabrications, myths, and erasures against the land of Palestine and its ancestral inhabitants, it is the latest atlas, The Return Journey, which is the most imaginative of Abu Sitta’s cartographies of resistance. It forms what Denis Wood calls “a narrative atlas,” one that tells a story we might otherwise overlook.

After the bitter 1993 capitulation that was the Oslo “hoax of the century,” a frustrated Abu Sitta, “por[ing] over maps, statistics, and figures for weeks,” makes this startling discovery, which he shares with a friend: “‘Israel is empty.’” He goes on to explain: “‘At least 90 percent of the sites are empty. Of course, there were lots of changes in the landscape, but this is the bottom line.’” The implication is that a Palestinian return would be logistically possible. Abu Sitta begins to work on his detailed “Return Plan,” which, in 1999, he publishes as Palestinian Right to Return: Sacred, Legal, and Possible.

In the new Afterword of his memoir, Abu Sitta explains the results of his extensive land research:

We found that 87 percent of Jews in Israel live in fifty-five localities out of 924, or only five percent of the total number of localities. The area they occupy is only 1,400 square kilometers or 6 percent of Israel’s area. This means that Israel is practically empty save for three cantons: Tel Aviv, Haifa, and West Jerusalem. It also means that Palestinians can return home without major displacement of Jews willing to live in peace in a free Palestine.

The Return Journey atlas thoroughly illustrates this Return Plan, “supported by maps and figures, including the identification of the villages of the refugees’ origin in all camps, the length of the road of return from all refugee camps to the villages of origin, and the time taken for return.” The refugees will travel between zero to a maximum of 35 kilometers home. It seems like a miracle, but one that is demonstrably possible.

The plan does not stop there. Abu Sitta has also organized a competition, now in its ninth year, for Palestinian architecture graduates to choose one of 550 destroyed Palestinian villages and to “produce a full reconstruction plan for it, based on the pre-1948 house plan and project it into the future with an increased population and complete modern amenities.” Abu Sitta, the Palestine Land Society, and the young students working on these reconstruction plans are not waiting for anyone’s permission. They proceed against genocide and ethnic cleansing; against the myth that Palestine was a land without a people (revealing instead that it is Israel, in fact, that is largely unpeopled); against the occupation of Palestinian Arab land by foreign Eastern Europeans with no connection to it; against the despicable indifference of world leaders. They proceed with bravery and audacity, with justice on their side, and with the voices of millions in the world rising in support.

Abu Sitta’s reissued memoir, together with his academic writing, and, especially, his narrative atlases together compose an imaginative cartography of return. His formidable work joins with the avalanche of superlative Palestinian research, scholarship, journalism, memoirs, poetry, fiction, film, art, music, and accomplishments in every field imaginable, from every corner of the world, past and present, to form together a non-negotiable march of return. It isn’t only a matter of resilience or idealistic aspiration, but, rather, a practical movement toward an inevitable, irreversible homecoming. Abu Sitta makes his case eloquently and convincingly and, in the darkness of these genocidal days, we would be inhuman not to believe him and not to act with haste toward the actualization of his just plan.