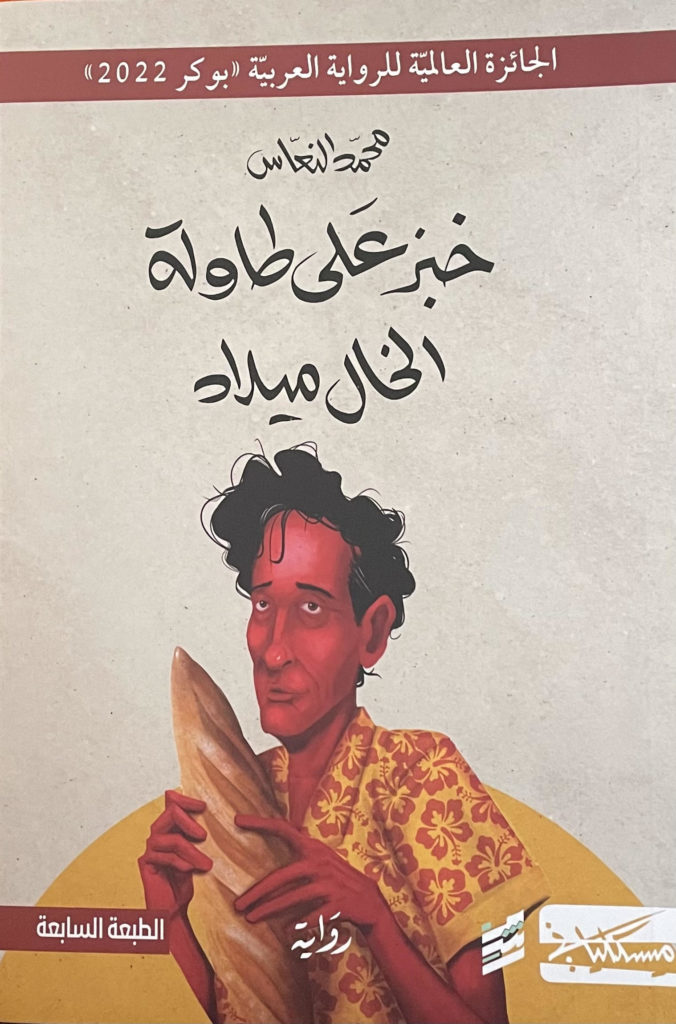

Exclusive excerpts from the novel Bread on Uncle Milad’s Table, published in Arabic by Rashm and Meskliani in 2021.

(1)

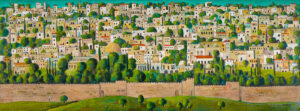

So, let’s start from the beginning. I am Milad Al-Osta. I’m told I resemble Cheb Khaled, when he used to be thin. I am the only male among my sisters. I was born at noon, in one of the alleys that overlook Cathedral Square, where I spent my entire childhood, scraping my knees on its asphalted streets. On Sundays, on our way to school, I’d observe the Roman congregation make their way into the cathedral whose front yard would later bear witness to the budding days of my first love. In Al Dahra, I ate the tastiest sandwiches, played football, and raced my mates to the Corniche to watch the waves crash within a short distance from our homes. That was in the late Sixties, before the winds of change came calling and a year, to be exact, before our Brother and Leader mounted his horse to free our country from agents, traitors, and foreign bases — just like they taught us in school.

In Al Dahra, I ate the tastiest sandwiches, played football, and raced my mates to the Corniche to watch the waves crash within a short distance from our homes. That was in the late Sixties, before the winds of change came calling and a year, to be exact, before our Brother and Leader mounted his horse to free our country from agents, traitors, and foreign bases — just like they taught us in school. In Al Dahra, I completed my primary education, whole-heartedly belted out the national anthem in the schoolyard, and went out on student marches in celebration of the first Jamahiriya while railing against Amreeka and the Zionist Movement. At fourteen, my parents and uncle decided to return to Bir Hussein, my grandfather’s home village, after they inherited vast fertile land, ideal for agriculture, building a home, and setting up a bakery — a fresh start in the same village I used to visit with my father to buy ricotta cheese, ma’soura, olives, and dates from his relatives. My father set up his kosha until the state’s extension plans for the government building next door included seizing his bakery.

I was four years old when I began to play with my baby sister. At five, I tried to make friends at school and within the neighborhood, which is where I became friends with Assadeq, Zainab’s brother, before we parted ways over petty trivialities. When I was six years old, I began to sit in the company of my three older sisters. I was eight when I began to help my father at the bakery. As soon as I turned fifteen, in addition to my chores that included cleaning the place and carrying the sacks of flour, he added the task of kneading the dough in preparation for my first batch of Muhawara, one of the easiest traditional breads to make. I was sixteen when my true love affair with bread began. It was right after my father let me in on the secret of his trade, the one he’d picked up from his Italian mentor, Signore Luigi Paintierri.When I was 18, my father died of lung cancer, and he now rests in heavenly peace next to my grandfather as well as the Prophet and his companions.

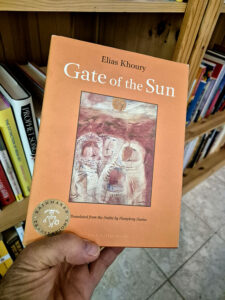

The bakery witnessed many political and social changes in the country. During the forties and fifties, most of Signore Luigi’s customers were Italians, English, and Maltese who came in for their western-style bread: baguettes that required varied and sophisticated techniques and took tedious hours to make, sliced bread, Sicilian sesame loaves, and of course the brioche. I used to listen to the legendary tales told about The Sanabel Bakery and how the people of Al Dahra, Casa Langues, and Municipality and Bin Ashour streets had never experienced anything tastier. My father apprenticed with the Signore until he was able to crack the code on flavor, paramount in this staple food gracing the tables of all Libyans. Signore Luigi held our people in deferential regard, loved them and sought them out to work alongside him. My father used to describe him as a “Sicilian from Arab roots,” but I’ve never really understood Italians’ relationship with our people. At the time, bread was a mark of disparity between the classes of society. Only Italians and a few wealthy high-society Libyans bought the fancy breads, and by pure coincidence, it turns out that one of the sons of this class, the Madame’s grandfather, used to buy his bread from my father’s bakery. As for the rest of the people, they ate Muhawara and Tannour, loaves bought at the traditional bread market.

In the sixties, with the boom that accompanied the discovery of oil, Libyans began to love Western-style breads, and as the numbers of educated, wealthy, self-stylized Italians, and former soldiers, who were able to buy these breads on a daily basis grew stronger, their teeth, on the other hand, only grew weaker, softening so they could no longer withstand the coarse Bedouin Tannour loaves they’d formerly ripped through. In the seventies, the Signore returned to Sicily, leaving my father in charge of the bakery. Initially, my father told us that the Signore had only left the place in his care until the time when he’d return to run it himself. But with the passing years, my father took ownership of the bakery, although, once, in a moment of anger, my cousin Al-Absi told me that my father had, in fact, stolen it. I’d heard that before, though, from Assadeq, Zainab’s brother. My father continued to hire Libyan laborers and encouraged them to learn how to make all kinds of breads, that is until our Brother and Leader decided that people should be partners in all businesses. My father, heeding the advice of my shrewd uncle, hastened to fire his workers before they turned on him. By then, the bakery was severely understaffed, with my uncle and myself the only two working alongside my father, although he’d occasionally call on the assistance of a few family members scattered about Bir Hussein and the entire area of Bir Al-Osta Milad — it is said my great grandfather used to own the entire region until the Italians robbed him of his land and turned it into farms that produced almonds, grapes and olives. My uncle then came up with the idea of employing Tunisian and Algerian workers, who, by law, own nothing in the country.

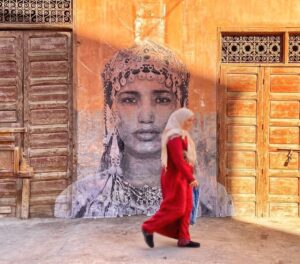

Libya’s Censored Novelist, Mohammed al-Naas, Revealed

With the new arrivals, the quality of the bread declined, and The Sanabel Bakery was reduced to the likes of all the other bakeries in the city. People turned their backs on the French baguette and the sesame bread, which were arduous to prepare and bake, and thus were duly pricey. Besides, the Leader rendered uniform the price of bread throughout the country, and The Sanabel Bakery went from a refined “Patisseria artisanali,” as my father used to call it, to an unremarkable one for the common masses.

My story with the bakery kicked off when my father fought with the janitor after he demanded a raise in his weekly wages. My father beat him up and told him that he hardly deserved what he was getting in the first place because as far as he was concerned, the bakery could hardly be considered clean. In the summer, I worked full-time and during school days my father would assign me chores either before school started or after it ended. Daily and unaided, I would sweep then wash the floors, clean the surfaces, and on occasion help in cleaning the ovens. I gleaned cleaning tips and tricks from my sisters. My father never missed a chance to slap me or raise his voice at me whenever I missed cleaning any bits of flaky dough that had dropped and splattered on the floors and surfaces. Sometimes he’d kick me out, but then he’d call me back and make it up to me with an offering of a hot loaf stuffed with fried eggs or tuna, which he’d prepare himself. My father was nervous, hot-tempered, and didn’t like people, in stark contrast to the gentleness with which he approached his dough, handling it with the utmost tenderness. I now recall an incident that happened on the dawn of a hot summer’s day, the sun barely risen, and the sweat already coursing down my face. I’d been busy mopping the place before I stood beside him to watch as he readied the first batch of dough that would go into the oven that day. I observed not only his use of a sharp razor blade to add the finishing touches to the loaves, but also how utterly focused and immersed he was in branding each one with his own trademark signature. He then took note of my curiosity, how entranced I was by the gleams of the sharp blade. He pulled me towards him until my body folded neatly into the side of his big bulk, and he said:

—Look! These markings are a baker’s signature. Each baker should have one.

—Is that your signature?

—No, of course not, it’s a cogent signature.

—Cogent?

—Yes, a nod to my Italian novitiate, you won’t find these markings on any bread, anywhere else in the entire city.

—I didn’t know that.

—Of course you don’t. You’re only a child. Now here, take it.

—The razor blade? It might cut me.

—If you’re going to hold it and tremble like a girl, then it’s definitely going to cut you. Come, slide the blade, gently, cut a slightly arched line along the length of the loaf, just like the one you saw me do.

—What if I ruin it?

—So what if you do? You think these savages will notice the difference? They’re ignorant fools who know nothing about bread.—I’m ready.

That was my first true memory with bread. The feel of the dough was as gentle to the touch as candy paste, the implanted blade sliding through with the ease of a finger scrawling something through fine sand. It was precisely at that moment that my hatred towards dough transformed into a love for it and a desire to learn more about it. But the best part of this memory is what my father said to me: “Someday, you’ll be the one who makes the bread.” But then it struck my father that the situation had turned intimate, so he cast a quick glance around the bakery and yelled in my face: “How come you’re still not done with the cleaning, you imbecile child? Hurry up and get back to work.”

(2)

What? Have I lost the thread to the story again? I apologize. But what else can I do? I spent the best days of my life in that bakery, and every time I think about it, I dwell on recapturing every detail, unaware of the passage of time. Maybe the Madame told you about some of them because I remember I told her everything in the days we conversed at her house while I taught her how to make bread and sweets before we’d have tea and I’d proceed to let her in on everything I knew about the secret lives of bakeries. I’ve never found anyone as passionate about bread as the Madame, the total opposite of Zainab, who never really enjoyed my stories about the bakery and my father; our conversations centered on discussing her workplace or other people, like when we’d speculate on what our neighbor had done to anger her husband, who raised his voice in their garden like a ghoul’s, but I don’t recall us ever talking about me for any extended period of time. She was the center, and my life revolved around her.

As I mentioned, after my phone call with Al-Absi, I tried to get away from my thoughts, diverting them instead to bread, contemplating size, smell, and texture. I’ve always succeeded in running away from things: in my youth it was from my cousin’s shed, then school, the military academy, and later myself. However, that afternoon, running away was proving futile. Al-Absi’s words simply followed me around, pervading every chore I undertook; whether it was washing the dishes, vigorously scrubbing the tray or handling the glasses, his words hovered close by while I tried swatting them away like flies, only for them to return as I washed the bowl of dough, and again as I left it to dry on the marble surface. When the washing failed to distract me, I organized the clothes I’d collected from the clothesline, and with the expertise of a retail worker, I folded and refolded my underwear, doing the same with Zainab’s lingerie, but before I was about to place a flower-adorned, pink slip trimmed with lace on the floor to fold in half, a new thought assaulted my mind: what if she had wanted to wear this particular piece? Terrified of the answer, I raced to haphazardly arrange the rest of the clothes, the need to escape more pressing than ever, but the phone conversation between us had me cornered even as I neatly placed Zainab’s clothes in their place in the closet from which I thought I detected the wafting scent of a man’s cologne; it could easily have been mine, and yet I’d long lost all recollection of my own perfume, instead inhaling the scent of my obsession after I’d thrown the bottle in the trash when I was done with it.

—Milad, wait. There’s something important I need to talk to you about. It concerns you.

What a night that was. Al-Absi’s shed is nestled under the shade of a blessed fig tree that stretches back to the time of my grandfather’s first mother, before my great-grandfather divorced her to marry another woman. The land it stood on had passed to my uncle, Mohammed, along with a dilapidated old house he tore down for a more lavish and modern one. Each night, Al-Absi would invite different folk from the neighborhood to join him in his shed, so that I rarely encountered the same face twice. Al-Absi had an attractive comedic character that appealed to the younger generation, and he was not only aware of all the news of the neighborhood, but also knew the name of every living soul that inhabited it, from its youngest kid to its oldest geezer, including its birds and trees. He was the neighborhood star. Though many had their doubts about his sanity, I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a mind saner than his. He never worked a day in his life: a rebel against the laws of society that required him to work. I can say that, other than the few times I saw him man the bakery’s cash register, he’d never once picked up a shovel, a mop, or any kind of tool, so that if ever he came up against any manual labour, he always made sure to shove it my way. He did pick up occasional odd “jobs” to make ends meet, but even those he considered as nothing more than passing interludes. He was satisfied with a salary he received from the Press Foundation, which he would visit once a month or not at all for several months, where he was supposedly employed in the administrative department despite the fact that he was neither a journalist nor in possession of a high school diploma.

Al-Absi was smart. I always wished I could be like him. He knew how to outplay the system to get what he wanted. That night, I found two of Absi’s “totems” in attendance — Absi liked to label his friends with monikers borrowed from the Age of Ignorance, like totem, Hubal, and Abu Jahl, among others. Although I was considered one of his “dearest” friends, it had been a month since I’d attended one of these soirees, but my unusual attraction to his world brought me back, yearning to spend the evening in his company. Absi spent the whole night drinking Bookha, which he’d distilled the week before, spinning tales of myths and legends. He was always finding ways to embarrass me by revealing personal anecdotes that had taken place between the two of us, all of which invariably ended with his saying I swear to God, cousin, you are a wimp!, to which I would smile, light up a local “Sport” cigarette, and take another sip of my Bookha, or else I’d get up to prepare a dish of macaroni for the assembled crowd. On this night, Absi had abruptly and angrily called it an early night for his two “friends” and kicked them out. The two had been discussing the plot of a movie in which Absi’s cousin, who had fled the village a long time ago, and was now considered one of the best writers and directors in the country, had criticized the neighborhood, calling out its folk by name. I knew that, if anything, Absi held nothing but insane admiration for his cousin and so I had my doubts as to his reasons when he stood up and drunkenly ranted at them to leave, his pillow raining down on them as he chased them out, all while still managing to hold on to his lit cigarette. All night, I’d been watching him plot a way to be rid of them, from showering them with a torrent of insults, to letting them know they were no longer welcome to drink, eat, smoke, or play cards at his expense. And so they’d left, knowing full well they’d all return the following night to do it all again. As I got ready to leave, assuming I, too, was being kicked out, he called out to me.

—What do you want Absi? Do you need more cigarettes?

—Of course I do, but first cousin, I want you to lend me your ears and listen clearly to what I have to tell you. Come sit beside me. More Bookha?

—No, thanks. I’m done for the night.

—One glass, as usual, never another. I admire your restraint, cousin. Only one of the many things I admire about you. Your contentment, kindness, easygoing nature, and your cigarettes. That’s not to say that there aren’t things I don’t like about you, or, actually, that the people of this neighborhood don’t like about you, in fact if you ask me, I’d venture to say that most people in this country wouldn’t like either, especially that you’ve become the joke they trade amongst each other to laugh at.

—A joke? I don’t understand.

—Yes, you totem. A joke. More than once I’ve tried to keep this from you to protect your feelings, but your fame has rocketed. Once, as your niece, Hanadi, was walking to college dressed in a pair of pants, I actually heard someone say: A family whose uncle is Milad.

—A family whose uncle is Milad? What does that even mean?

—It means people here see you as a cuckold. I know your sister is doing her utmost to raise her children alone, but where’s your authority Milad? You are now in the position of her father. You are the head of the family.

—My niece? She’s respectable. She walks in the street with eyes cast to the ground.

—That’s true, but she dresses in pants, goes to university and is enrolled in the Department of Arts and Media. It’s a department filled with fallen women and tramps. I worry that some bastards may take advantage of her, don’t you?

—Yes, but I trust her and so does her mother.

—You see? That’s why I wanted to be honest with you, cousin. Hajj Mukhtar, May God Have Mercy on His Soul, would be deeply displeased if he were alive to witness the state his family is in today. My father tried to reason with your sister, Sabah, this morning but she threw him out of the house, can you imagine? Who does that to an old man?

—It’s unimaginable, and I told her, that no matter what, he was still her uncle, and it wasn’t right for her to raise her voice in front of him, even if he had been wrong.

—Yes, my father may have overstepped but he wasn’t wrong. Milad, open your mind, clear that hay from your barn, and set aside your stupidity and focus. We are one family. Any affront to one of its members is an affront to the entire family name.

—And the bakery? I said, my face crimson with anger.

—What about the bakery?

—Your father stole it from me. I said and walked out.

This was the first time that Al-Absi had had opened up to me. It was a painful confrontation after which I decided that I would never return to his shed for as long as I lived.

Did you go back?

Argh, I’ve forgotten, let’s go back to the beginning.

Hello, thank you for the translation, and I’m wondering if I could get the novel Bread on Uncle Milad’s Table, The full version I mean translated into English, I would really appreciate it.

many Thanks