Can a Syrian artist have it both ways: lauded by the regime and still remain critical? After exile in London and Beirut, Sara Shamma moved back to Damascus. Her hyperrealistic paintings capture the chaos and madness of the world today.

Sara Shamma is a successful artist from Damascus, who travels back and forth from her exiled life in London to her art studio at home. Born in 1975, she grew up in Syria of the 1980s and 1990s, under the reign of Hafez al-Assad, whose son Bashar assumed authority on the passing of his father in 2000. What were the arts like under the Assads, during Sara’s formative years? “The damage of the Assad era on art and culture,” opines Syrian photographer Omar Berakdar, in conversation with TMR’s senior art critic Arie Amaya-Akkermans, “is too deep. Hafez understood the artists’ need for freedom of speech, and therefore kept the art scene under heavy surveillance by Syria’s security apparatus.”

In her own way, Sara Shamma is a prototypical Syrian artist, both an insider and an outsider, neither an activist nor someone with overt political views, yet who nonetheless acknowledges that politics in a country like Syria are inevitable, and that she has perhaps benefitted from a degree of privilege. When her career in her Damascus was just beginning to flourish, she was in demand as a portraitist, and she was asked to paint Asma al-Assad, Bashar’s wife. This isn’t a commission she would consider today.

“When I did that portrait,” she explains, “it was during a period when I did a lot of portraits for many people. At the time, I painted businessmen, young people, and the wife of the president — I said, why not? I will do it… It was an important experience for me to dig inside each person. I still sometimes do portraits, but the last portraits I’ve done were for an actor and actress that I exhibited at the Royal Academy of Art. It was something I enjoyed doing because they are friends. Their faces were inspiring to me.”

A little more than a year into Syria’s civil war, near the end of 2012, a car bomb exploded in front of Sara’s flat where she lived with her husband and two young children. The next day, she took the kids to Beirut, and soon thereafter, she obtained an Exceptional Talent Visa, and moved to London. However, she would return to work in her Damascus studio as often as she could, sometimes every two or three months. Critic Amaya-Akkermans remembers, “She was tolerated by the Assad regime, which means she was more than tolerated by the authorities. Sara Shamma had an exhibition at the National Museum in 2024, which would have been impossible without the approval of [the Minister of Culture]. I understand that the show was attended by the culture minister…Shamma’s work has also been exhibited by an art gallery called Art House, owned by Nader Kalai. Her National Museum exhibition reopened in January. I have no insight into her actual political views.”

I asked the artist if she felt her work was political.

“I think politics are in our lives, whether we like it or not, but I don’t think you’ll find that in my art. I’m not an activist, and yet there is something political in all my my work, even if it’s just a self-portrait, because these are my views on what’s happening in the world. I’m not interested in politics, per se, but there are politics in your life, between you and your friends, between what’s happening in the world and in the news, and in countries everywhere… That’s what I believe.”

Sara Shamma was born in Syria’s capital to a Syrian father and Lebanese mother, into a family steeped in appreciation for art and culture (her mother owned a private art gallery). She began painting at the age of four, and went on to study at the Adham Isma’il Fine Arts Institute in Damascus, where she graduated in 1995. Three years later, she received a B.A. in painting from the Faculty of Fine Arts at Damascus University. After the civil war broke out, she re-established her life in Beirut, with her husband and two young boys. Before long, they would restart their lives yet again in London. When she and I spoke the other day, the family had returned to Damascus, where the artist spends most days in her studio, painting.

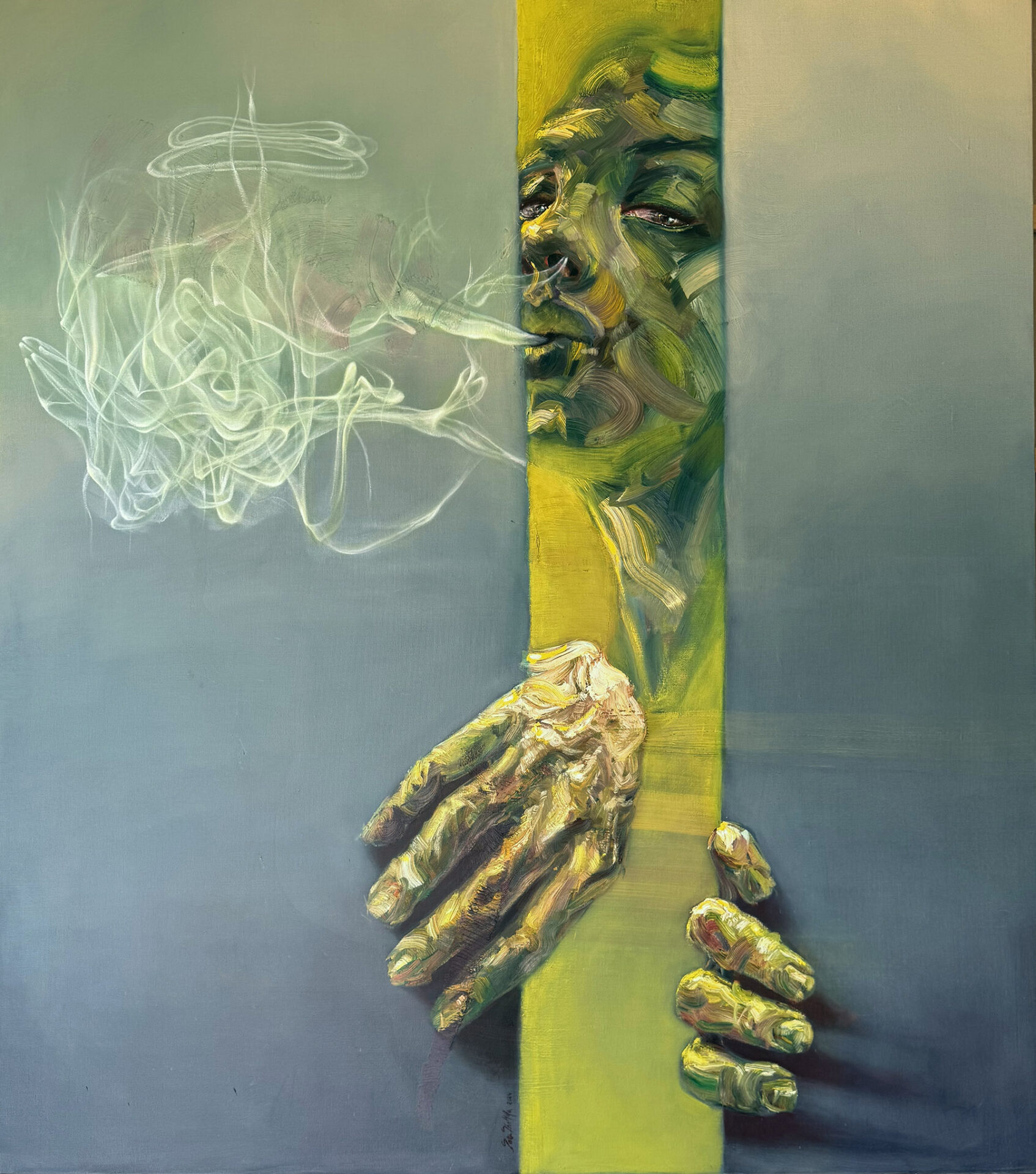

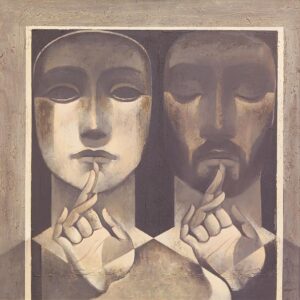

As an art lover, and as the person until now responsible for the look of The Markaz Review, I have been intrigued by Sara Shamma’s work, since I came across one of her portraits from 2021. Her hyperrealist style is raw, emotional, and intense. The women, men and children who stare out at us from her paintings are real people. I feel that they convey precisely the mood of our September issue, OUT OF OUR MINDS, as we struggle to maintain our sanity, in what seems like an uphill battle in a world that feels increasingly chaotic and unpredictable, from political upheaval to global crises, including genocide and starvation in Gaza. With endless war in Ukraine and Sudan, and still a volatile Syria, many are searching for ways to stay grounded amid isolation and uncertainty.

The power of Sara Shamma’s work is that she reveals a no-nonsense tendency to face her own mortality, even as she confronts the world as she finds it. Sara is particularly fascinated by the human condition, by the traps of the mind, the effects of trauma and loss, and death. Two of her London shows explored painful subjects, including World Civil War Portraits in 2015, and Modern Slavery in 2019. World Civil War presented portraits that revealed the weight of war and conflict on the soul. At the time, she told a reporter, “I want to bring these dead people to life. I want you to see them, look through their eyes.” She went even further, insisting that Syria’s civil war wasn’t just about those displaced or killed in Syria. “It’s not just a Syrian civil war anymore,” she said. “It’s become a world civil war.”

And here we are, ten years later, helplessly watching the genocide in Gaza, asking ourselves if we’re in a similar purgatory — if this has become not just the Palestinians’ but the world’s genocide.

“I think so,” agrees Sara. “War is a game everybody wants to play in the Middle East. Everybody wants to fight here. Gaza is no different, and it’s much worse than what’s happening in Syria.”

Investing herself deeply in her work, when she was an artist-in-residence with King’s College, she collaborated with the King’s Institute of Psychiatry, and the Helen Bamber Foundation, visually representing stories of women who were trafficked in the human slave trade of today. She even included self-portraiture, as though she, too, were one of the unfortunate victims of modern slavery.

In view of her hyperrealist, expressionist work, I wondered whether the portraiture of Francis Bacon or Lucian Freud was an influence, and how exactly she came to develop her own particular style.

“When I was very young,” she admits, “in my university years, or maybe before, I knew about Francis Bacon and about Salvador Dalí, and Lucian Freud as well. I was very impressed with their work, because for sure, I have something similar going on inside me… I think Salvador Dalí, more than other artists, has been more of an influence, because I was very young, 13 or 14, when I would dive inside his universe. The surrealistic mentality is similar to how I think, because I’m always aware of the subconscious; I try to reveal the subconscious mind and dig inside the subconscious and find creativity. I’m very much interested in everything related to humans, especially our psychological states and our suffering and the way that we deal with death, and how we live life. Maybe that’s why Francis Bacon has some influence on me — I need some kind of expressionism. As I’m very much interested in portraiture and the thick brush stroke, you could say that one can see something of Bacon and Lucian Freud, in my work. But to tell you the truth, the artist who influences me more than Lucian Freud is Rembrandt. He is the first real influence on my work. Rembrandt and Dalí.”

War is a game everybody wants to play in the Middle East. Gaza is no different. It’s much worse than what’s happening in Syria.

In her bio, she writes that, “Death gives meaning to life.” Obviously there has been a lot of death with the Syrian civil war, and in Gaza and Lebanon, and so she writes that she uses art to study “the impact of grief and deep internal emotions.” Is she obsessed with death, in the way that Heidegger talked about man as Ende-Sein — being toward death, existing for death?

“Well, life is going to end,” she says. “So it is very precious and very meaningful. Accepting death means accepting change. When you leave a country, when you go to another country, you leave something behind, and you kill something inside your personality as well. You accept this, in order to be able to live something new, or in order to be able to be reborn again. So in that sense, for me death is very important to be understood. That’s why, if you understand death and if you accept it, you will live your life happily, because you know that it’s going to end at any moment. And I think death is the main trigger for creativity. We create because we want to remain. We want to be immortal, in a way — artists, human beings, engineers, doctors; anyone. So I think death is the main trigger for creativity. And when you create, you kill yourself in a way, because you want to forget everything about your knowledge, about your past, even your artistic knowledge, and start again from zero, as if you don’t know anything. That’s why I think death is very important.”

Despite the uncertainty of life in Syria today, Sara seems adjusted, and not neurotic, about what lies in wait for her.

“Being aware of death and accepting it isn’t easy, and I think most people don’t accept it, and that’s why they lie to themselves. They try to believe in religion and create all these things, that there is something else after life. But I think when you really believe that this is happening and there’s the end of everything, you enjoy life more, you create more, and you’ll be able to give to yourself and to your loved ones, to all the people, more.”

Thus, the grief, the emotion, the madness one finds in the work of Sara Shamma is not morbid, it is not necessarily intended to be dark, but is there to remind you of the light. She emphasizes in our conversation that her work is not at all intended to be a panegyric for death or insanity. On the contrary, she says, “You’re just aware that there are many important things in life. There is a lot to be inspired by, there’s a lot of beauty, it’s there and you appreciate it, because you know that it’s not going to last.”

I notice a white line or a scratch, sometimes it’s right down the middle, as though Shamma is cleaving the subject, or the world, in two.

The artist tends to do copious research, to read and take photographs and work with models, as needed. She sometimes paints for six or seven hours a day. “I collaborated with a dance school for several projects. And whenever I see people I find inspiring, I ask them to pose for me. Children have also inspired me a lot in one of my projects, because I was obsessed with children because I had children, as simple as that. I use models, but most of the time, I change their faces because I just need the body, and most of the time, I love to create faces.”

Self-portraiture was more common for Sara Shamma in her earlier work, although now and then she still brings herself into a painting. “I think after I had children, my life changed, and I became more obsessed with others than with myself… I still enjoy using myself as a model now and then; sometimes my body, mostly my face.”

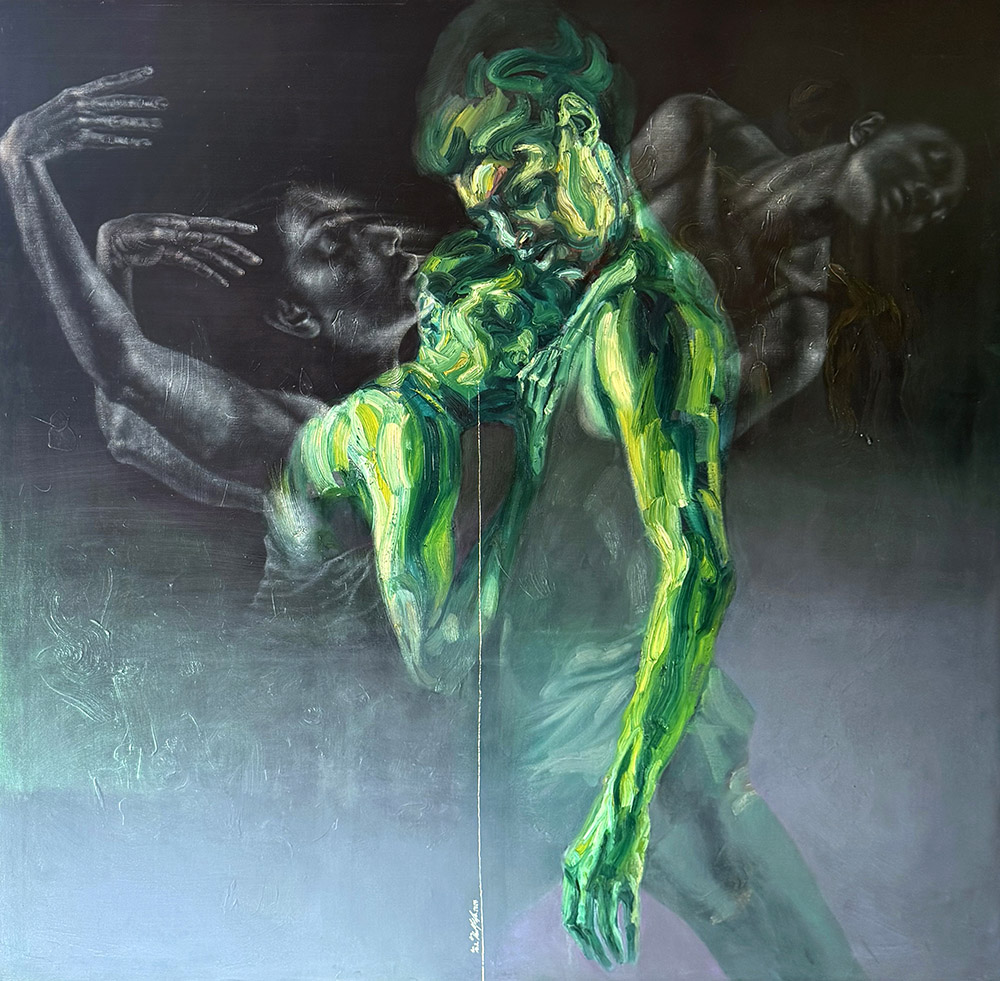

In her latest show, Interference Green, exhibited this summer in Beirut at the Mark Hachem Gallery, the artist uses deep hues of green and thick brush strokes to create memorable characters that have plenty to say. I find her use of the color makes me think not only of Syria but of Palestine, and the green rind of the watermelon, a symbol of the Palestinian flag and of freedom, as well as the green of Iran and its Green Movement. Green being the color of Interference Green, what does it mean, why was it important, and not just for this exhibit? If you look back in time at Sara Shamma’s work, it is often a dominant color.

“I started exploring the green color a few years ago, after I moved to London, maybe in 2018. I used to use a lot of red and black before. I think it’s a normal transition from red to go to green, because every color has an opposite color: the negative of red is green, the negative of yellow is purple, the negative of blue is orange. The negative of black is white. So, it’s a natural evolution. If you play with young children and give them, let’s say, a red color to paint with, they are still unconscious, and if you ask them to then pick a color, they immediately pick the green one. Subconsciously, after you work with black, you work with white. After you work with red, you work with green…

“And maybe because when I lived in London this year, the sun there, you know, is different from the sun in the Middle East. It hits you at a different angle, it hits you in the eyes differently, and the color of the sun is so different. I always see red, because it’s always hitting my eyes, and I have to close them, and there is red. So when you see a lot of red, and you open your eyes, you immediately see the opposite. You see the green.”

I wondered how it happened that she returned to Damascus in September 2024, three months before the Assad regime fell. Did she have a spy on the inside tell her Bashar al-Assad was going?

She laughs. “Everybody asks me the same question, but no. We went back, and I did the retrospective exhibition at the National Museum here in November, which I had been planning to do a long time ago, before I left Syria, back in 2012. I thought back then that I would be exhibiting outside Syria because of the war. I decided to keep one or two paintings from each year to exhibit one day in a large, retrospective exhibition of my work.”

As we think about contemporary Arab identity, or contemporary human identity, it’s a fact that we aren’t just one thing… Sara Shamma, to be sure, is Syrian, and Arab, but she’s also an artist, a woman, a resident of the UK. Does she feel that in her work and her consciousness, perhaps, that all of this is encapsulated as she creates art?

“I think so, because I’m Syrian, but I’m also Lebanese, so I have three countries (I’m a British citizen now as well). I have these three countries inside me. And for sure, you can see the influence of each area in my work, I can see it clearly. I think it’s very enriching experience to be part of three countries, and to to feel you really belong to these three countries. I don’t feel I’m a stranger in the UK, and I don’t feel like a stranger in Lebanon, either. Damascus is my city. Damascus is me — it’s inside me. But I feel very at home as well in London and in Beirut, and in Lebanon in general. I can see all these worlds, small worlds inside my work.”

Speaking of worlds, I notice that in some of her more recent paintings, there appears to be a white line or a scratch, sometimes it’s right down the middle, almost as though she is cleaving the subject, or the world, in two. In some of her other paintings, there is a similar scatch somewhere, not always in the middle.

She says that she has been doing this to her work for quite some time now. “I do it with the cutter, after I finish the painting. I find it very interesting to cut or scratch it. This line that I draw is very sharp, and stands out from the painting itself, from the texture of the painting and the harmony that the paintings have. To me it creates a kind of thread that you are holding one or two meters away from the painting, that creates another depth. It sort of pushes the whole painting backward. So it’s very important to me.”

Art is always in the eye of the beholder, and it all depends on how much you value representational art, but for this writer, certainly the work of Sara Shamma must be counted when surveying today’s Syrian artists, along with the work of Tammam Azzam, Mohamed Al Mufti and others. Certainly it is the case that Sara Shamma’s works are in the homes of private collectors, as well as in public collections around the world. The big question is, what does the future hold for art in Syria, and for Syrian artists in the diaspora, who have not chosen to return as Sara has, and may remain in exile?

There are many, according to TMR’s Amaya-Akkermans, who provides the following list of prominent artists working abroad — Diana Al-Hadid currently showing at MSU Broad; New York-based Syrian-Armenian Kevork Mourad, who works between sound, drawing and sculpture; the young painter Anas Albraehe, based in Beirut; architect Khaled Malas, also based in New York, known for his multidisciplinary projects as a part of art collectives; visual artist and sculptor Nour Asalia, in France; veteran artist Youssef Abdelke, still active in his 70s and possibly living in Dubai; the photographer from an Armenian background who trained in his father’s studio, Hrair Sarkissian, now in London; the photographer Jaber Al Azmeh, in Doha; sculptor Chaouki Choukini, also based in Paris for decades; and the multidisciplinary artist Tammam Azzam who produces sculpture, graphic design, and digital work in Delmenhorst, Germany. War has scattered some and brought others like Sara Shamma to the city and country that once inspired them.

What will the history of Syrian artists of the 21st century tell us, later, about Syria, art, and ourselves?