Select Other Languages French.

In the Global South, abstraction has long been regarded as part of the history of modernism and the different strategies that 20th century artists devised to circumvent censorship, but what if abstraction could be a much more powerful tool for thinking about deep time and memory?

Torn Time at the Institute of Islamic Art in New York closes on the 20th of October, while Bilgé: 1975 at the Sapar Contemporary, also in New York, closes on the 13th of October.

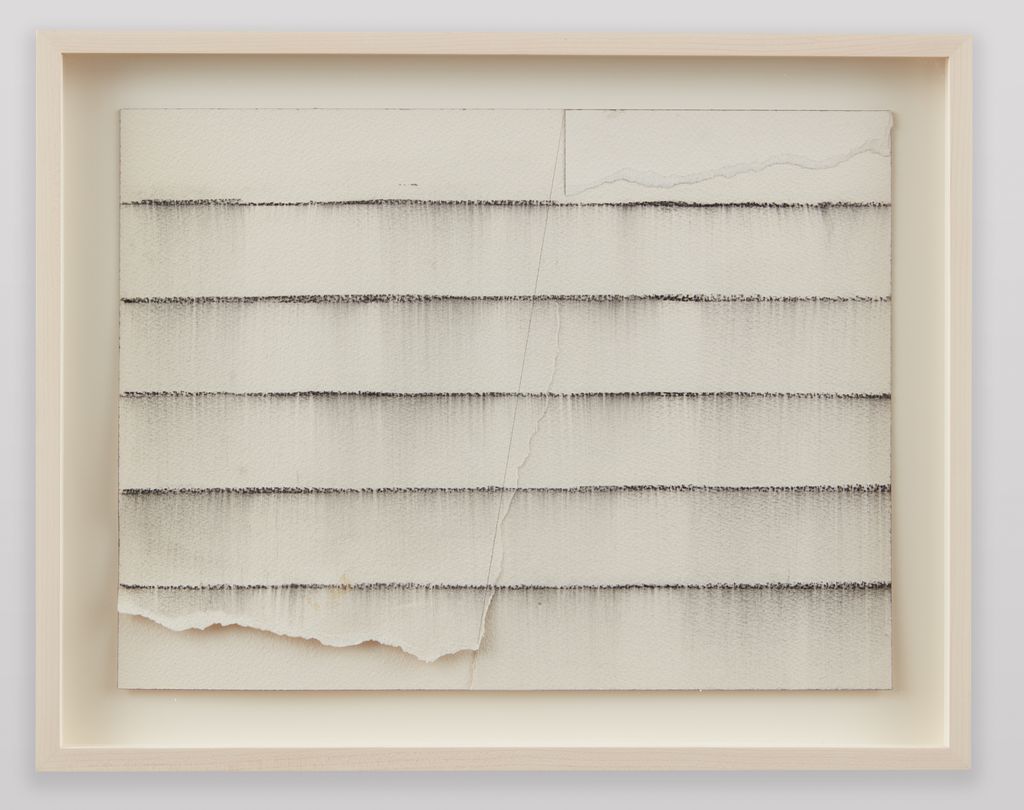

At the beginning of 2017, when a fresh wave of violence and unrest hit an already embattled Turkey, the soft and fragile drawings of the late Bilgé Civelekoğlu Friedlaender (1934-2000), known as Bilgé, seemed to capture that atmosphere of vertigo and unsteadiness: Lines of string, pencil strokes and flying shapes that would either disappear or break down and become a gaping wound that swallowed reality. But the works had been made 40 years earlier, in the 1970s. In the exhibition Words, Numbers, Lines at the old ARTER in Istanbul, the Turkish-American artist filled the void of minimalism in the tense Turkish canon. But it was a strange sensation to be in the presence of moving time arrows, against the background of minimalism, which in the West is always associated with formalism and internal consciousness.

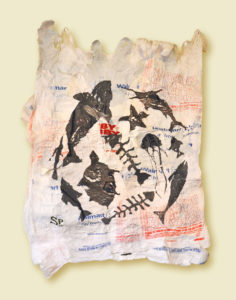

Those cracks in the paper allow historical time to pass through, oozing out like a viscous substance, contaminating everything. In the same year, when I curated the exhibition Pictures of Nothing, I included a drawing by Bilgé from same period of the 1970s, “Untitled (Torn Time),” thinking about abstraction not as the historicist periodization of modern art, but as a multitemporal process that has shaped art since the emergence of symbolic thinking during the Ice Age tens of thousands years ago. But a narrower interpretation of the artist’s work as a meditation on time and the impossibility of depicting it on a two-dimensional system of points and lines, grounded in abstraction, has become dominant since then: A number of her works from ARTER traveled to Neues Museum Nürnberg in 2018, for the exhibition Border of Time.

Then, more recently, Bilgé’s current solo exhibition at the Institute of Arab and Islamic Art in New York, curated by Mohammed Rashid Al-Thani, was titled Torn Time, after the work exhibited in Istanbul almost a decade ago. References in Bilgé’s diary entries — Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Roland Barthes — confirm her Western pedigree and place her firmly in the company of other American artists of her generation, like Agnes Martin or Eva Hesse, who made minimalism “warm,” engaged with the durational aspect of time, and enlarged abstraction with the feminist gaze. But the question of the movement between time and history would remain unanswered: Under what conditions does time cease being abstract? How does time become physically embodied?

Serious interpreters of Bilgé are at odds with defining what exactly is it that she does in her work: “Abstraction in transition,” “an art practice woven with reflections of Eastern mystics,” “diffusion,” “spiritual abstraction,” or “romantic abstraction.” Although they avoid orientalizing tropes, these vague concepts do little to secure her place in the Western canon. Al-Thani’s curatorial concept is loyal to the tradition, conceived as an “engagement with the line and space,” but he does go one step further, wanting to think through the ways in which Bilgé departs from American minimalism: It wasn’t only disobeying the formalism of American abstraction, but a turn towards nature, embodied in what he calls her transcendentalism — introducing a dualism between reason and spirituality that the artist would perhaps reject.

Overall, it seems particularly difficult to offer a wide-ranging overview of Bilgé’s practice, considering that this signature work from the 1970s, which has brought her posthumous recognition, would substantially change through the following decades, and especially after her return to Turkey in the 1990s. Already in the early 1970s, the artist felt uneasy with the label abstract. “Pure abstract aesthetics. Pure aesthetics. Yes, but my work must relate to life — to my life — to my pain — through it we must live together,” she jotted down in her diaries. In her final years, she recalled in an interview that her earlier works had been abstract — “there were no forms recalling the outside world” —, but she points out a shift in 1982, when “three-dimensionality had emerged, installation had emerged and symbols had started to come into play.”

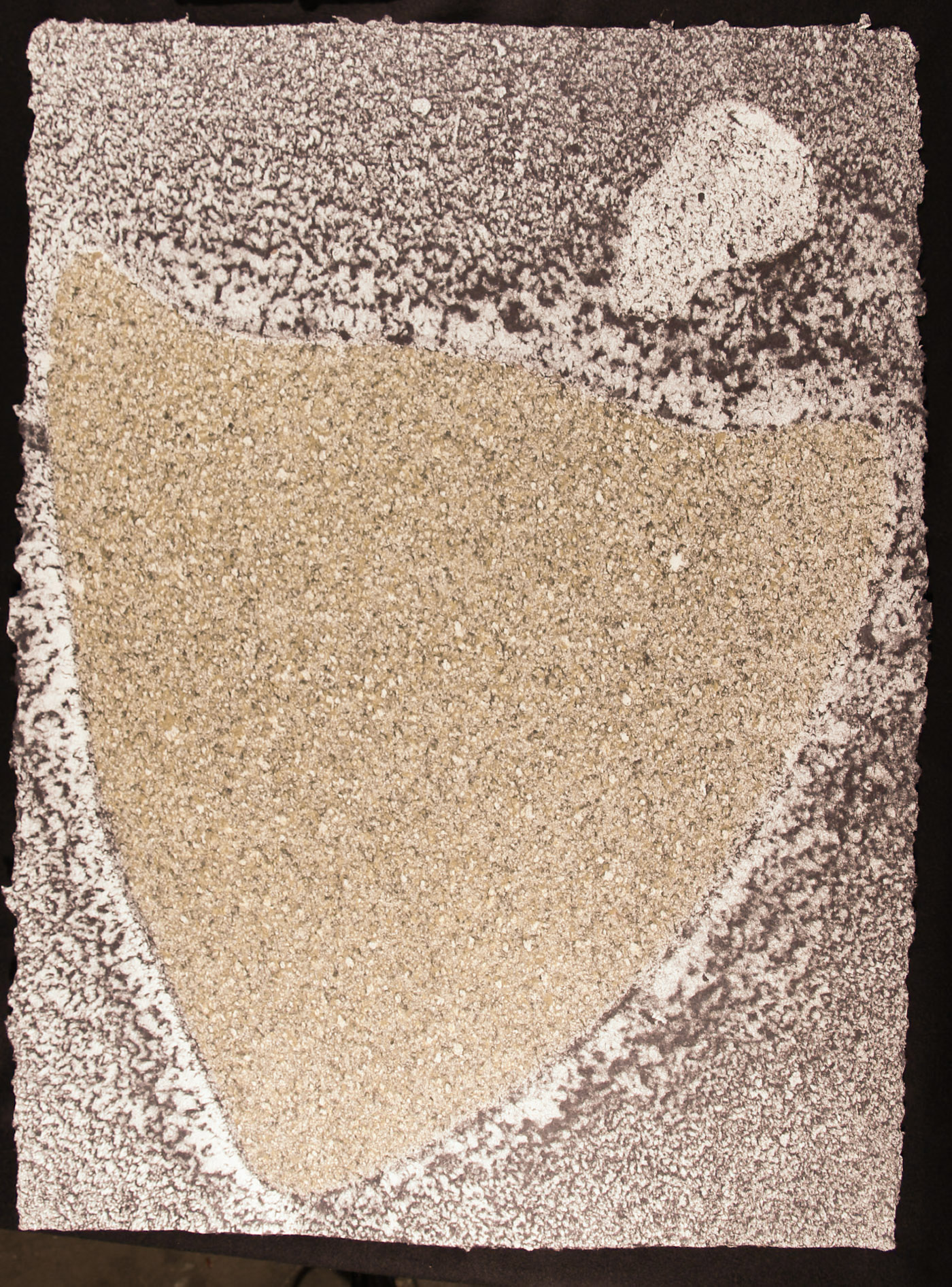

Born in Turkey in 1934, Bilgé Civelekoğlu (later Friedlaender), emigrated to the United States in 1958, completed a masters degree in painting at New York University, and transitioned from painting to drawing, paperworks and subtle installations that lie at the border between postminimalism, ecofeminism and the new materialism. She died in Istanbul in 2000. Nearly every posthumous exhibition since then, including Al-Thani’s, has invoked an anecdote about water from 1972, when the artist dove down in the Tongue of the Ocean in the Bahamas, from where she returned transformed, and set upon a new conception of what painting could mean: “I am engaged in an effort to invent painting again and made paintings that were not paintings. I made paintings depicting water, and that is to say, depicting the spacelessness of space.”

Both IAIA’s exhibition and the most recent show at Sapar Contemporary, curated by Barbara Stehl — dealing with the pivotal year of 1975 — showcase that indeed, the aquatic imagination takes over Bilgé’s new idea of painting after 1972, in the form of undulation, waves, creasing and chaotic motion. But the Tongue of the Ocean might not have been the only lasting influence in Bilgé’s shift: The relationship between the artist and the South Pacific has never been explored, and it might yet open up new possibilities to link her ecofeminist practice to the ontological turn in the social sciences, and ultimately to her final narratives about Turkey, which attempt to bridge the gap between experienced time and the incompleteness of history. Bilge’s spouse was then the anthropologist Jonathan Friedlaender, who conducted extensive fieldwork on the Solomon Islands.

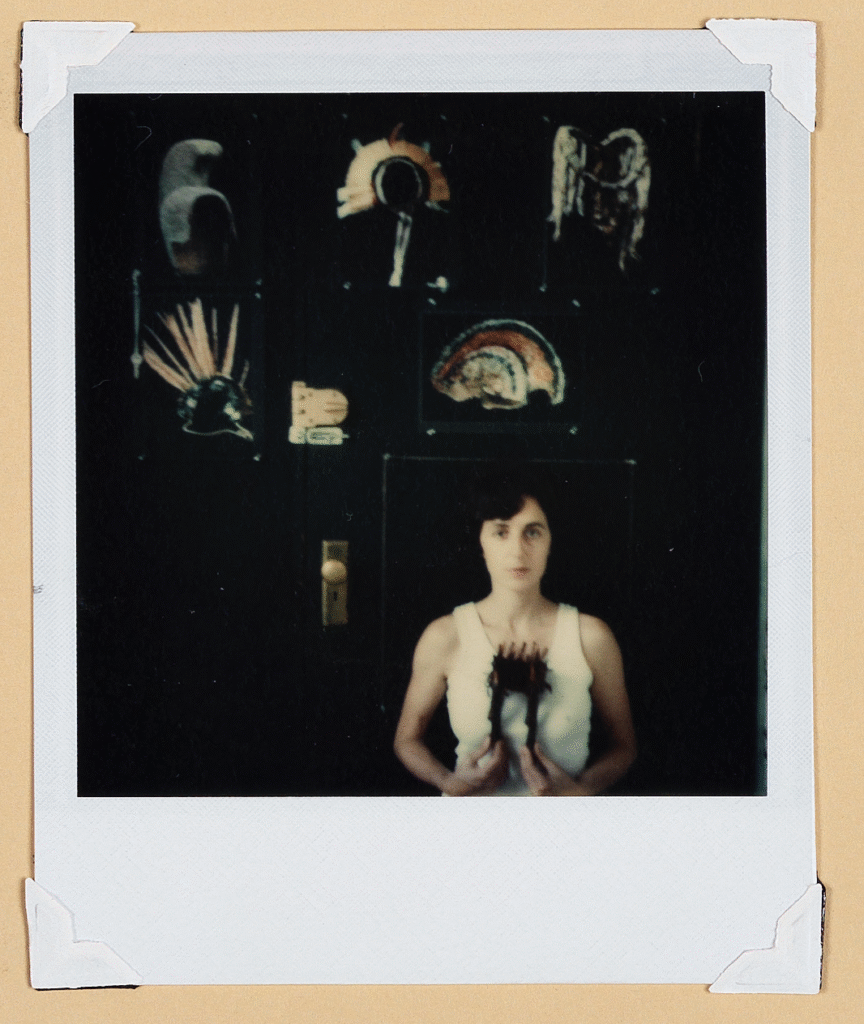

In 1978 they traveled to the island of Bougainville in Papua New Guinea, after which she seems to have grown disenchanted with the confinement of Western epistemology. “Time and space have merged into a solid, static cube, a geometric prison and I feel very anxious,” she wrote in a letter from this period. “What is reality and whose reality is real? Now I can say feeling it in my body that reality is a state of mind and every state of mind in one person or different persons is as real as any other.” Bilgé’s shift away from pictorial formalism towards a relational world in which everything is interconnected, echoes the anthropological imagination emerging in the next generation. But these scattered fragments do not construct a full picture, which would require perhaps looking into the photographic archive of Prof. Friedlaender (many photos taken by Bilgé), and the collection of objects from the Solomons — masks, musical instruments, tapa clothes, and carved figures, among others, that he donated to Temple University in 2007.

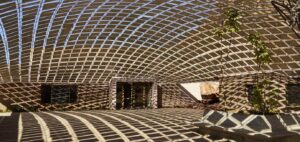

How did Bilgé look at these artifacts, both ancient and contemporary? We don’t know. But over the years after 1978, the water metaphors melted away with the abstraction, and instead she found herself in a deeper, ambivalent time, working with markings and traces, hand stencils, sculptural objects shaped by the elements, and three-dimensional interventions and installations. There’s an iconic work from the beginning of this new period, and her first installation, “River, House, Book” (1981), which has been exhibited twice alongside the works from the 1970s, because of an aesthetic resemblance, but it couldn’t be any more different: Not only did Bilgé begin working with handmade paper books as art, but here the books stand as the semi-temporary thatched roofs in Bougainville, on the Solomons.

She recounts in a letter from 1980 that, “More and more I feel my art as a sublimation of other things I would have liked to have done such as dance, or be a naturalist, an underwater archaeologist. But nothing is ever lost and hopefully there’s time to bring all my interest under one hat. One of the enchanting parts of being in New Guinea was the fact that I was in nature 24 hours a day. Living in the Sago palm leaf hut, there was no separation of the outside from the inside.” The structure in the installation, at times resembling a boat, as well as a tent stretched out on sand beds, follows the construction technique of the dwellings of the Nagovisi people, almost floating on the Aita River. The double metaphor of navigation builds on from earlier her works, but the Nagovisi idea of a temporary shelter might be lost without the Pacific context.

Roof making with Sago leaves in the archipelago of Melanesia, was regarded traditionally as a communal activity — women would prepare a meal, and men would go into the swamp to cut the leaves from the tree, and the women would remove the hard joints at the back of the leaves, then men would sew the leaves onto the cut out stems from betel nut trees. Bilgé mentions in her correspondence the many challenges of Bougainville — building a house, learning some of the local pidgin, mosquitos. But this return to a nature indistinguishable from the realm of culture, might have profoundly defined the rest of her practice, that came later to be defined as ecofeminist, but often without any further qualifiers than simply the use of natural materials. Bilgé’s ecofeminism is perhaps closer to the idea that all objects radiate life and have agency, and the refusal of linear conceptions of time.

The matrilineal society of the Nagovisi is only scantily studied (Jonathan Friendlaender’s study of the Solomons was exceptional in its temporal expanse), and we can only make vague associations with monumental architecture from the Solomons in relatively recent periods — a vast and culturally diverse archipelago, but the pattern of elevated pedestals, sandfills, and thatched roofs surrounded by tools and ritual objects represented in Bilgé’s installation, resembles the architecture of shrines excavated in Melanesia. When discussing the 1981 installation years later, the artist explains that the depictions of water after 1972 forced her to seek a three-dimensional space that she found in paper as a medium for installation. Between the dive to the Tongue of the Ocean and the Nagovisi dwellings, new constellations emerged. There are two puzzling drawings of outer space in Torn Time at the IAIA exhibition I had never seen before, Cosmos Pastel I and II (1975), one of which closely resembles images of the Pleiades cluster, from the Palomar Observatory sky survey 1949-1955. In Pacific mythologies, the Pleiades are associated with the beginning of the year, agricultural cycles and celestial navigation. Is there a connection? We don’t know yet.

“For three or four years, I only made water paintings, but they were not paintings that resembled water, these were paintings that depicted the soul of water. Everything has a soul, the soul doesn’t just belong to us. As I was depicting water I also changed the space and slowly the third dimension began to emerge,” she wrote in 1998. Almost simultaneously, Bilgé encountered the new material world for her ecological art, the pluridimensionality of sculpture and installation, and the vibrancy of matter — objects in the world are alive and ensouled. Cosmologies in the South Pacific emphasize similar orientations as the later Bilgé: The importance of place-specific memory and knowledge, a cosmos in which humans are not separated from other elements, being, and spirits, and the importance of ritual to reactivate world-making.

The question of linear time is more difficult to encapsulate. Anthropologist James Flexner tells us European colonialism collapsed time and space in ways that the further something was from Europe, the more remote it was in time. The Solomons that Bilgé encountered were obviously not in a naive primitive state untouched by colonization, but as archaeologist Tim Thomas points out about the Pacific, “We need to produce analyses critically engaged with how the Western tradition influences archaeological understanding, but also acknowledge how that tradition is simultaneously a ‘tradition-in-the-making’ influenced by its own encounters with local materials and records and with other ideas, rather than circumscribed by its own preoccupations.” Bilgé’s subsequent dialogues with the Western tradition would remain mediated by this encounter.

Thomas continues, “The region began as a purely imagined realm, based on speculative theories about the shape of the world beyond European experience.” In the Pacific, Western time bends rapidly and percolates on the basis of spatial disjointedness — so many land masses, waterways, migrations, social arrangements, and enormous distances, to the point that reality cannot be flattened into the homogeneous settler time of Australia and North America. All the different pasts and the present are always together. For Bilgé’s practice, this means the opening up of a new space, which you might call shamanic, mythical or even indigenous, in which this togetherness is materially possible, blurring the lines between nature and sculpture, between object and memory, between place and time.

Back in Turkey, Bilgé’s first exhibition, Cedar Forest: Tools and Offerings (1989), an installation based on the Gilgamesh epic, draws on the oldest literary Mesopotamian text dating back to the 3rd millennium BCE, and reconnects the artist with that deep time that she encountered in the Pacific, but this time in her home territory: She was quick to point out that text fragments and monuments connected with the epic were found at the archaeological sites of Boğazkӧy, Carchemish, Urfa, Sultantepe and Zincirli, all of them in Eastern Turkey, near her hometown of Iskenderun, in the Northern Levant, part of the same world of Gilgamesh. The epic is the story of a tyrant king who becomes a wiser ruler after his companion Enkidu is killed by the gods. Following his death, Gilgamesh seeks immortality but fails, and yet returns to Uruk to rule justly.

In the epic, Gilgamesh and Enkidu travel to the Cedar Forest, a divine sacred place guarded by the demi-god Humbaba, located in the mountains of Lebanon, to gain fame by felling the trees. Their disrespectful actions offend the gods, leading ultimately to Enkidu’s death. Bilgé focuses on this episode as the first myth about environmental destruction in the region and its consequences, and goes on to create an installation of the Cedar Forest, which came back to life in 2020 for a group exhibition about ecofeminisms. Instead of collapsing linear time and space, the artist brings together different experiences of time in parallel — mythical, physical, chronological; all constructed around a sacred space, marked by ritual objects that do not have any specific function; they stand for the ambiguity of the passage of time itself.

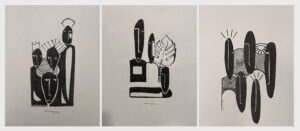

Soon thereafter, she produced a limited edition book for Galeri Nev in Istanbul, where she recounts through etchings, depicting the entire epic, the journeys of Gilgamesh through destruction and rebirth. And here it must be added, how important were artist’s books throughout her career, not only as the expression of three-dimensionality she sought in paper. “The book is the record of human intelligence. Intelligence is the ability to perceive the world with all our senses and the ability to express the perceived in a relationship. A book is a relationship. It is a relationship between the creator and the created, the creator and the world, the book and the world. The book form is an affirmation of human intelligence and the wish to communicate this in a relationship.”

Many of her artist books introduce a vertiginous multitemporality to her exhibitions, for they blend seamlessly with her abstract works from the 1970s to form a continuum, which is continuous only in appearance — the water paintings make it clear that time is formed also by cracks and interruptions. But it would be inappropriate to reflect on Friedlaender’s travels in the Pacific and eventual return to Turkey as an ‘indigenous’ shift, because indigenous is not an essential condition but a collective identity that is produced externally through colonization and that is neither stable nor permanently fixed. In the Middle East, in settler colonial contexts such as Palestine or Turkey, we often struggle with the distinction between native and indigenous, in a region where a combination of natives and colonizers both engage in brutal dispossession of peoples.

In fact, the status of indigeneity in anthropology is often predicated on ontological, essential difference, whereas artists like Bilgé Friedlaender do not recognize such alterity. There are no clear markers between periods and ideas; deep past and unfolding present are constantly mixed. Indigenous scholar Sarah Hunt writes that loaded words such as epistemology or ontology do not come to mind to those thinking of indigeneity. “What comes to mind, instead, are stories. Stories and storytelling are widely acknowledged as culturally nuanced ways of knowing, produced within networks of relational meaning-making.”

And this is precisely what happens in Bilgé’s work: By telling a story, whether it is the Tongue of the Ocean, Bougainville, Gilgamesh or the poetry of Rumi, she is allowing different temporal modes to emerge out of a place or situation-specific story, including cumulative layers of knowledge, experience and perception, but the final destination is still uncertain. Near the end, in one of her final exhibitions, she also tells her own family story, but there’s so much about Bilgé’s works beyond the 1970s yet to be discovered.

A reviewer of the ecofeminist show in 2020, for example, writes that though the political and intellectual contexts of ecofeminist art have shifted dramatically over the years, “one constant is the way practitioners look to Indigenous cultures for alternatives to the capitalist paradigm.” Positions of this kind see all indigenous cultures as near identical and static, endowed with special wisdoms coming from the past that could magically resolve our predicament. The issue is that this indigenous knowledge is in the present, just like our capitalist paradigm is in the present, both are here with us…

During the last decade of her life, in Turkey, Bilgé’s undeciphered drawings, Bronze tools, earthworks and performances, some of them still unseen, simultaneously archaic, Neolithic, shamanic, Pacific, Anatolian, Mesopotamian and contemporary, provide an arch of time that pivots only in the present, where she is inviting us to dwell in this fragile world, one that is always endangered, ending and beginning, expanding, creasing, shrinking and folding. It’s impossible for us to reconstruct the entirety of what Bilgé and Jonathan Friedlaender might have seen on the Solomons, either through the photographs, artifacts or even their works and words, but it’s this indeterminacy, unknowability and undecidability of the past that endows it with power to become visible again; and this power lies dormant not in scientific facts alone but in accrued temporalities within us, fleeting traces, and imaginaries, such as the installation “River, House, Book” (1981). Archaeologist Catherine Frieman, who also studies the deep past, writes that “The material basis of our field lies in the fragmented remains of things, structures, creatures, landscapes and bodies. These data are not just incomplete but irreparably broken; we do not know what is not represented, in most cases we cannot and will never know.” Bilgé nods in agreement, from half a century ago: “The whole thing is a fiction. What we are trying to communicate through fiction is reality.”