Malu Halasa talks to the director of a new documentary about the cause célèbre of Reyhaneh Jabbari, executed in Iran for the murder of a man who attempted to rape her.

Malu Halasa

As monolithic and all-powerful as the Islamic Republic of Iran is, its secret vulnerabilities are revealed by the troubling but illuminating documentary Seven Winters in Tehran, directed by Steffi Niederzoll.

The film recounts the tragic story of a near rape victim who killed her perpetrator in self-defense, the failed campaign of a mother to save her daughter from execution, and the determination of ordinary people in facing down a corrupt system. There is no happy ending, yet Seven Winters still inspires and empowers.

In 2007, 19-year-old Reyhaneh Jabbari was studying computer science. In earlier times, as shown from home video footage featured in the documentary, she was a happy, bubbly young woman who had a bright future ahead of her. She worked part-time as an interior decorator, and was approached and befriended by Morteza Sarbandi, purportedly a plastic surgeon. He had plans, he said, to renovate a new clinic space, and he invited her to an empty apartment.

Reyhaneh was taking measurements and making notes, when Sarbandi accosted her. To defend herself, she grabbed a knife on a nearby table. He goaded her, daring her to stab him — he said he could take it. She did, in his shoulder. Reyhaneh fled after a friend of Sarbandi’s came to the apartment. Later that evening, Sarbandi died from his wounds.

In the middle of the night Reyhaneh’s mother, Shole Pakravan (pronounced Sholeh), woke to find policemen in her house. They took her eldest daughter away. For 58 days her family was not allowed to see or talk to Reyhaneh. The police tortured her and threatened to arrest and torture her mother and two sisters. Reyhaneh gave a false confession, which was used as evidence against her in court.

“You Should Have been Raped”

The first judge who heard the case was sympathetic to the young woman’s plight. His replacement, a hardline religious judge, told Reyhaneh it would have been better if she had been raped to avoid the situation she was now in. Reyhaneh was convicted of Sarbandi’s murder. Under the Islamic state’s qisās, an antiquated law of blood revenge or retribution, the family of the murdered victim can determine Reyhaneh’s punishment.

During the seven and a half years she spent in prison — the seven winters in the title of the film — her mother Shole waged a campaign to uncover the truth of what happened to her daughter. It came out that Morteza Sarbandi was not a plastic surgeon after all. He trained people in self-defense in the Quds Force, a militia headed by Qasim Soleimani, who was assassinated in 2020, in Iraq. Sarbandi had many businesses. His work for the Quds Force, formally part of the IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corp) in part explains why Reyhaneh was vilified in the Iranian press, with a campaign of disinformation, rumor and conjecture that darkened her character. Shole’s campaign to save her daughter went viral on Facebook. Iranian officials were asked about Reyhaneh’s case whenever they made state visits to Europe.

Relatives kept vigil outside the final prison to where Reyhaneh had been taken, and filmed Shole covertly, as she waited to learn if Reyhaneh had been granted clemency or was going to be executed. This was the initial footage seen by Steffi Niederzoll. It was shown to her by Reyhaneh’s relatives, who were refugees in Turkey. Niederzoll, then on holiday, had known of Reyhaneh’s case from news reports in Germany. An artist and film school graduate, she was writing her first fictional film treatment. On repeated trips to Turkey, she and Reyhaneh’s relatives became friends. They wanted her to make a film about the case. Although she wasn’t sure if she was the right person to do it, she still wanted to help them.

Meanwhile in Iran, after Reyhaneh’s death in 2014, Shole had become a well-known human rights campaigner openly critical of the country’s death penalty. After a state interrogator threatened her, she and Reyhaneh’s youngest sister Shahrzad Jabbari fled Iran for Istanbul.

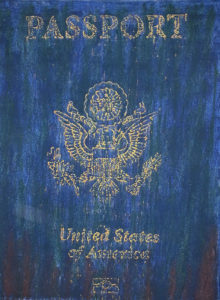

Niederzoll was in a shop, copying material from Reyhaneh’s relatives that she planned to take to Germany and get translated. She looked out of the window and recognized Shole. Their chance meeting convinced Niederzoll that she should make the film. In time, Shole and her daughter settled in Germany. Several years later her second daughter, Sharare Jabbari, was able to join them, although Reyhaneh’s father, Fereydoon Jabbari, denied a passport, remains in Tehran.

Seven Winters in Tehran took five years to complete. Niederzoll had wanted to go and shoot in Iran, but was warned off by Iranian friends. The film could not have been made without the extensive archive Shole smuggled out of the country. Nor would it have been possible without the Iranian production team, and other anonymous people, who secretly filmed in Iran for the documentary.

Reactions to the Film

My conversation with Steffi Niederzoll takes place via Zoom between the film’s European premiers. After the Berlin Film Festival, Seven Winters in Tehran was screened in London at the Human Rights Film Festival, at the Barbican; it also debuted in Paris at the same time.

TMR: What has the reaction been to Seven Winters in Tehran?

STEFFI NEDERZOLL: People have been so touched by the movie. After every screening we had such strong Q&As. Some Iranians especially opened up. One said, “I never spoke about it but my father was executed.” Another said, “I never spoke about it but my brother was killed.” Or “I never spoke about it but I was raped by a mullah.”

I get goosebumps because it’s so — [the director’s words fail her and her voice wavers] — I don’t know, we always think that art can change something. I always had this idea that art can connect people. I’m crying because it’s really touching. We’ve been collaborating with Amnesty International and other NGOs against Iran’s death penalty. People want to take action.

TMR: The second trial judge’s statement, that it would have been better if Reyhaneh had been raped was a clear indication of what Iranian women face in their country.

SN: This was the trickiness of the disastrous blood revenge law. In the case of Reyhaneh, Sarbandi’s eldest son, Jahlal, “owns” her blood. He can forgive or not forgive. As soon as Shole started to speak to Western media and said that Reyhaneh was nearly raped — the chances that Jahlal might forgive Reyhaneh grew smaller. The more Reyhaneh’s family fight for her honor, the less she will be forgiven by Jahlal’s family. That’s the super weird aspect of all of this.

TMR: The story seems one of conflicting honors. In the film, it’s obvious that Jahlal wants to make a deal. He says he won’t call for Reyhaneh’s execution if she withdraws her charge that his father tried to rape her. That’s the honor of his father and his family. Then there is the honor of Reyhaneh — in the Islamic justice system she’s not allowed agency to protect it nor herself.

SN: Shole wanted Reyhaneh to erase [take back] the rape charge. Shole begged her daughter, “Save your life.”

TMR: Understandably.

SN: However, Reyhaneh wanted to stay with the truth. I think she could not stand that someone so powerful could just get rid of what had happened. She thought: “This is my truth, my dignity. This is the only thing I have.” She had lost everything. She wanted to get married and have children. She also knew if she came out of prison, everything would be different. The only thing she has left is her dignity. This is her strength and this is why she became such a hero.

TMR: In such a fraught situation, it’s easy to see people in stark terms, black or white, right or wrong, good or evil. Yet, Seven Winters is a nuanced film, and one gets the sense that for Jahlal and the rest of the Sarbani family, calling for Reyhaneh’s execution, will not bring them peace.

SN: It was always important for me to not enter this “black and white” terrain. I don’t want to say Jahlal’s a victim — because he’s also a grown man, so he could have also taken a different decision. But for me, he is a victim of this patriarchal society. He has to fulfill something. I find this decision the state forces on him quite horrible. I feel sorry for him. However, he can also be seen to be doing wrong when he says he forgives. There is a whole system that will approve of him. When he’s not forgiving there is another part of society, which will claim him.

I didn’t read the whole SMS conversation between Shole and Jahlal because part of it was lost. Of course, we showed only a tiny bit in the movie. After a while, at one moment I had the feeling, wow, okay, he is really considering pardoning her.

Then in another moment we see how his speech changes. He becomes very strict. I think he was also under pressure.

TMR: In the film, one gets the impression he is wavering.

SM: He cries, “What should I do?” If a guy like that cries in front of people, it is quite strong. I wrote a book with Shole, so I’m deeply involved in this case. Both families got all this wrong information. The Sarbandis were so sure that Reyhaneh was a sex worker. Of course, if you hear that she is a bad woman, you assume that she must have no morality and entirely capable of killing your beloved father …

There were a few moments in this material that make no sense — and we’re speaking about a lot [of material].

TMR: A wealth of documentation must have been smuggled out of Iran.

SN: Shole has a massive archive because she collected everything she could find. We’re speaking about police reports, investigation reports. I read over 100 investigation reports from the time Reyhaneh was tortured. And, of course, Shole paid money for every little piece. She always found someone who maybe knew someone who could perhaps get a copy of this document or the other. She collected everything she could get over the years. For example Shole still has everything that was in Reyhaneh’s bedroom, even — [Niederzoll pretends to pick up a piece of tissue and presses it to her lips to remove lipstick.] The first time she gave any of Reyhaneh’s clothes away was to the Ukrainians because we’re seeing so many refugees in Berlin.

Beyond Terabytes and Gigabytes

TMR: Seven Winters couldn’t have been made without mobile phone footage, which includes intimate moments of the family together when they were allowed to visit Reyhaneh in prison. You also included home movies that were shot when Reyhaneh and her sisters were growing up. How much material did you have?

SM: Normally, there are so many terabytes or gigabytes, so many hours. But I really can’t say because much of it was in different formats. I had very old footage on VHS, Beta SP; mini disc; cassettes recordings from the children, lots of pictures, and mobile images, but really from 2007 onward, when the near rape took place.

I had amazing audio recordings from the prison visits. For example, in 2007, Shole started to research what happened. She referred to it as the “Parents’ Investigation.” So you can tell that this one recording of Reyhaneh’s voice in the film is from this time. Shole says to her, “I record now, speak now.” Then you hear Reyhaneh describing the incident in detail, and how it happened.

TMR: You built a model of an Iranian prison, which was reconstructed from photographs the family took inside of Evin and later in Shahr-e Rey, prisons where Reyhaneh was incarcerated. The model was filmed for the documentary. Because of this element of fictionalized reality, I erroneously assumed the photographs showing Reyhaneh’s court case were also a reenactment of sorts.

SN: Those were documentary photos by the official court photographer, in Iran. She took those pictures. They are from the courtroom. There was one moment in 2014 when this photographer sent those pictures to Shole, and Shole started to use them in her campaign. Because of this, these pictures were widely available.

Two of them became iconic, so I contacted the photographer, and officially requested the use of them. She sold them to us, but of course she wrote in an official statement, “In the name of God, I have to tell you I was witnessing this court, and Reyhaneh was claiming …” It was a disclaimer, or that’s how I interpreted it. So the government can’t go back to the court photographer, and say, you supported a movie that was against us.

Corruption on Earth

TMR: Since you didn’t go to Iran, you relied on the production company Zebra Kroop. Surreptitiously they shot film footage in Tehran for the documentary. If they had been caught, they would have been charged with efsad-fil-arz (corruption on earth). This is the same charge that has been brought against people who’ve been arrested during the Woman, Life, Freedom protests, like the rapper and outspoken regime critic Toomaj Salehi. Some of the protestors who were accused of this “crime” were executed. You must have been aware of the risks Zebra Kroop faced?

SN: Of course, it was super dangerous what people were prepared to do for me. A lot of people took great risks for this movie. Zebra Kroop are specialists in smuggling out material, and shooting illegally in Iran. They didn’t go into the apartment where the alleged rape had taken place, but they were just outside. That was dangerous because the apartment was next to a government building.

TMR: Seven Winters was started years before the women’s protests, yet the film amplifies the grievances of women on Iranian streets and the difficulties they face, living under a hardline Islamic regime.

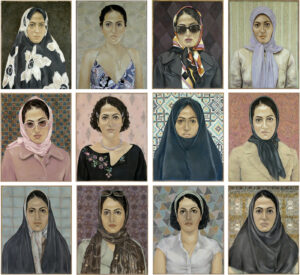

SN: In this movie I think you can see the tragedy because Reyhaneh is not a special case. Before her, women had the same destiny as Reyhaneh. Now, afterwards, a lot of people share her destiny, and not just women. Even so, there are layers [of complexity] when we speak about being a woman in Iran. I think you can see behind them a system of oppression that doesn’t change. Over the years it sometimes looks a bit different because of the way women wear their headscarves. For a few months they can do it like this, or like that, but nothing really changes.

—Malu Halasa