Select Other Languages French.

Panahi’s film is a journey of dread: a wrong turn here, a bureaucratic mix-up there, the absurd persistence of life intruding on vengeance.

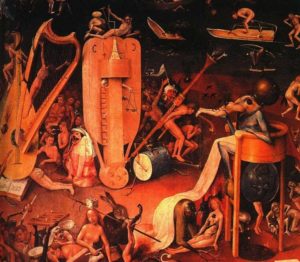

Revenge is trauma disguised as justice. You see it manifesting in conflicts all over the world, whether it’s in the Middle East, West Africa, or the Balkans. Each act folds into the next — a vicious cycle that sometimes has gone on for generations. Revenge becomes the last language left when words stop working.

Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just an Accident (this year’s Palme d’Or winner at Cannes) is about that hunger: how the need to even the score corrodes the soul, whether you’re a state, a movement, or one man who believes he’s found the person who once tortured him.

Panahi knows something about confronting power. One of Iran’s most celebrated filmmakers (No Bears, 3 Faces), he has spent years working under restrictions — banned from travel, periodically detained, and forbidden from making films. Yet he has continued to create, often in secret, using confinement itself as subject and setting. His 2011 documentary This Is Not a Film, shot almost entirely inside his Tehran apartment while he was under house arrest, is an early sketch of this idea: a man trapped in a room, talking to the camera, turning imprisonment into expression. In It Was Just an Accident, that private purgatory becomes mobile — the van replaces the apartment as a closed space that moves but never escapes, circling endlessly between guilt and retribution.

“It really begins with a small sound: a prosthetic leg tapping against the concrete on the outskirts of Tehran.” Vahid, a former political prisoner, looks up and freezes. That limp — he knows it. The man walking ahead of him, years older but unmistakable, must be the interrogator who brutalized him in captivity. Or so he believes.

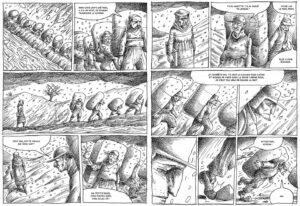

Before long, Vahid attacks, binds, and hauls the man into a white van. He’s convinced he’s delivering justice. What follows is a grim road movie stripped of forward motion: a journey of memory and rage looping back on itself. As Vahid drives through the city, he visits others who suffered under the regime, asking them to identify the captive. Some recognize him. Others hesitate. The camera lingers in that uncertainty — truth as an unstable pulse.

It really begins with a small sound: a prosthetic leg tapping against the concrete on the outskirts of Tehran.

Panahi’s filmmaking hides its precision under stillness. The van isn’t just a vehicle; it’s a moving purgatory, a box of ghosts rolling through Tehran. We see reflections in mirrors, half-lit faces, the twitch of a cigarette in an unsteady hand. The city outside hums indifferently — vendors shouting, traffic snarling, schoolchildren darting past — while inside, time seems to thicken.

This is a journey of dread: a wrong turn here, a bureaucratic mix-up there, the absurd persistence of life intruding on vengeance. Only halfway through do you realize that nothing violent has actually happened on screen. Panahi builds tension not through blood, but through uncertainty. The violence is internal, imagined, coiled tight. The film keeps asking whether revenge, like memory, can ever be trusted.

You think of Spielberg’s Munich, where Israeli assassins lose their souls avenging the dead; of Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing, where perpetrators re-stage atrocities as heroism; of Michale Haneke’s Hidden, where guilt itself becomes the stalker. Panahi belongs in that uneasy lineage, but he moves differently — quieter, closer, more suffocating.

But categorizing It Was Just an Accident as merely a revenge film undersells it. It’s a film about revenge as pathology, about how rage can impersonate righteousness. Vahid thinks he’s restoring balance. Instead, he becomes the mirror image of his tormentor: methodical, obsessed, sure that pain can purify. The longer he drives, the more he starts to resemble the man he’s captured. The more he seeks truth, the less capable he becomes of recognizing it. He’s not purging his trauma; he’s replaying it.

The man in the van — blindfolded, trembling — could be his torturer. Or his reflection. Panahi makes sure we’re never sure. We want Vahid to be right, not because we’re certain, but because doubt feels unbearable.

The film’s moral center lies in a single question: What if he’s wrong? That possibility is like a spirit hovering over every frame. When one survivor finally asks, “Even if it’s him, what will you do then?” the line lands like a verdict.

That uncertainty reverberates far beyond Iran. Watching It Was Just an Accident while Gaza burns, the parallel feels inescapable. Israel’s leadership speaks of “teaching a lesson,” flattening neighborhoods in pursuit of deterrence. Hamas responds by invoking decades of dispossession and siege. Both sides speak the same grammar of payback, each act presented as the inevitable answer to the last. Panahi’s van could be the region itself — sealed off, circling the same streets, unable to see that the destination no longer exists.

But vengeance doesn’t stop at borders anymore. It’s seeped into our feeds, our politics, our group chats. It shapes how we argue, how we remember, how many live online. Outrage is our new language, grievance our badge. The apps know this — they feed us fury like oxygen, teaching us that punishment counts as participation.

Everyone now carries their own guillotine. The comment section is the new public square. The line between moral outrage and mob justice has vanished. We don’t talk to understand anymore; we talk to condemn. Forgiveness has become suspect, almost obscene. The more we strike out, the more righteous we feel, and the more trapped we become. And the more the algorithm rewards us with more ammunition. The personal and the political run on the same circuitry now.

Panahi’s van, endlessly circling, feels prophetic. The repetition of outrage, the looping of pain into performance — it’s all there. We scroll, condemn, repeat. The world runs on grievance. Anger feels like belonging; forgiveness, like betrayal.

And yet, It Was Just an Accident isn’t hopeless. Sometimes it’s even funny. Panahi allows tiny eruptions of absurdity and grace to break through the tension: a radio talk-show drifting through static, an old woman confidently misidentifying the wrong man, a laugh that sounds like a gasp for air. These moments don’t deflate the film — they humanize it. They remind us that even inside the darkest rooms, life insists on being ridiculous.

What makes the ending so haunting is its refusal to define itself. We see the van parked somewhere remote. The camera stays fixed as day turns to dusk. There’s the telling sound of the prosthetic leg. Is it real or imagined? The oppressor might escape, or he might not. And that could mean Vahid or the guard. As the viewer ponders this, the film simply cuts. No catharsis. Just silence. Maybe it’s mercy. Maybe surrender. Or maybe exhaustion — the point where vengeance collapses under its own weight.

Like Haneke’s Hidden, the film ends with the camera lingering on a scene that refuses to explain itself. In Hidden, a single static shot outside a school hides a clue that might unlock everything — or nothing. In Panahi’s film, there is no justice, no confession, no closure — just the faint rattle of a prosthetic leg somewhere in memory, and the echo of a question that won’t go away: What if the thing you need to heal is the thing keeping you alive?

Across nations, timelines, and screens, that question feels terrifyingly current. We live in an age built on cycles of retribution. From Gaza to X, we call it justice, but mostly it’s ritual. It Was Just an Accident doesn’t moralize; it just shows us the trap. Vengeance doesn’t end violence — it memorializes it.

Panahi offers no answers, only the van, idling in the dark, engine running. Outside, the city keeps moving, indifferent as ever. Inside, vengeance waits for its next driver.