In which a woman ponders the fate of the individuals who left behind their garments, now long forgotten, at the laundromat.

Salah Badis

Translated from the Arabic by Saliha Haddad

Winter became short, less than three months with rain falling only for a few days. The day I left my architectural tutorials at Bab Ezzouar University it was raining. I don’t remember if it was a Tuesday or a Wednesday. I took the train. Every day the trains carry people between Algiers and its eastern suburbs, every single day — students, workers and the jobless. The trains watch them grow, fall in love, break up and then return them back drunk, sad or happy. The trains offer them empty seats, or a few centimeters in which to stand. The trains collect them from the station platforms and throw most of them out onto the platform of Reghaïa. You should all see how the train empties at Reghaïa — suddenly, all at once.

Mom left the laundry receipt on the fridge, sticking it on with a small, magnetic plastic orange. She’d done it before she left for my sister’s house on Monday. This way she was sure I wouldn’t forget the coat. We never neglect retrieving our things, neither clothes from the laundromat, nor the baklava trays from the baker. She also said that she was staying at my sister’s, in Tipaza, until the weekend, which meant that I would be alone in our apartment.

On that first night I ate some of the lentils she’d left, and peeled two oranges. Many people avoid coffee and oranges in the evening. I never think of doing this, sleeping for me is like a train making its way through the night … nothing stops it.

I got off the train, amidst the human wave. I walked from the station to the post office, and turned left towards the laundromat. There wasn’t a sunrise for there had to be a sunset; the sky was dark. When I opened the glass door to the laundromat, it was like stepping inside a dimly lit bubble of warmth.

I love Reghaïa, but it’s an old love. I love what Reghaïa used to be — before the earthquake when the number of its inhabitants was small and the place calm. But now it’s becoming worse every day: The sidewalks are crumbling and their tiles are broken underfoot, especially in winter. All my memories of this place are related to childhood. I feel like some kind of a cocoon has been punctured and I am waiting for the right time to fly away but I don’t know which horizon to go towards, although the sea is always beautiful.

I took out the laundry receipt and presented it to the employee, who took it and disappeared behind a huge washing machine. I waited for him, with thoughts of Reghaïa swirling around my head. On my left, covering the entire wall, was a huge poster I’d never noticed before. It was of Building 15, which had collapsed in the last earthquake, and while the picture was a bit blurry because the poster zoomed onto a small picture, it was the building. I remembered it.

Mom says that I look like my father when I spread out my papers and architectural drawings in the living room, close the door, and become sensitive to the least bit of movement or noise. Maybe it’s true; mothers always attributed the bad traits of their children to their fathers. But it isn’t true. What I really want, is to be left alone. That’s why I’m always thinking of going away.

I like being home alone for the longest possible time, even though I’m the only one living with Mom after my sister married. Particularly in winter, I feel like I’m living in a faraway place, as if no one knows me, as if my days here are stolen days from a future life.

I waited in the laundromat. I looked at the racks of clothes, hanging above the old washing machines. They resembled a dark cloud suspended from the ceiling, or a black hole, from where the dim, heavy light entered the shop and drowned everything in it. There were many pants and coats — I don’t know how many exactly, but they exceeded well over a hundred.

It was obvious that these clothes were from the past. They were old fashioned, the texture of their cloth harsh. Some were patterned with small, black and yellow squares. It was also obvious that the clothes were up there because they had been forgotten. I thought of the coat my grandfather wore in an old photograph that used to be in our living room, before it disappeared at the end of the 1990s. I remember we had painted the house, and when we finished and brought the furniture back in, the photo had disappeared. That was before the earthquake.

That photograph haunted me for years. I asked my mom about it many times, but she didn’t know what had happened to it. And even though we are one of those families that don’t discard their possessions — unlike families who left their old clothes in the laundromat — we still couldn’t find the photo. Some time ago I’d read an article about middle-class families that never throw away any of their furniture or renovate it, and keep living in houses that look like museum storerooms. Of course, Reghaïa isn’t a town of middle-class families — it doesn’t aspire to be. However, there are some families that were almost middle class, before the earthquake came and wrecked everything.

The employees at the laundromat have strange features. Their faces look like cheese triangles, their chins pointed, and their cheeks prominent and red. It’s as if they’ve come from another country.

The degraded color of their hair is somewhere between blond and yellow. It looked like hair spotted with bleach. At the time, I thought it was because they had been exposed to the chemicals in which the clothes are washed, and that they would die, similar to people living in small American towns where factories have contaminated the groundwater — just like in the Erin Brockovich movie. Those inhabitants lost hair and skin and grew sick with terminal diseases.

No one remembers Building 15 today, although it was the biggest building in the town. Only people from the eastern suburb know it, because they used to pass it on their way to the beach between Reghaïa and Aïn Taya. But it collapsed, and with it the dream of Reghaïa, which had vacillated between being a town full of workers and the displaced or establishing itself as a more stable suburb. Reghaïa had only that one tall building. But retailers crammed the ground floor with so much merchandise during the nineties that when the earthquake happened, the building seemed to crash down on itself in three distinct stages, like there was even too much for the brute force of nature to get through. Most of its inhabitants succeeded in escaping. I remember that.

Was it possible that in the earthquake the owners of all these forgotten clothes died or lost their homes? Something must have happened to them. Were they killed in an accident or escaped town? And when the police found their corpses they didn’t pay attention to the small, folded pieces of paper in pockets of the dead, receipts that would have connected them to the laundromat.

When the employee came back with my coat, I gathered my courage and asked him about the hanging clothes.

“These … they’ve been here for two years.” He told me. “And these,” he gestured towards a row on the right of the door, “They’re hidden out of sight … they’ve been here for so long …”

“Wow,” I said.

He smiled at my bewilderment and then repeated his last words: “For so long.”

This is the first time I noticed the clothes at the laundromat. I used to come and leave our dirty clothes without looking around or starting a conversation with any of the employees.

Why do people forget their clothes in a laundromat?

The problem with Reghaïa is not only did it lose its tallest building in the earthquake, even the green and open spaces that people escaped to from their falling homes on the day of the earthquake have now disappeared, and been replaced by new buildings. So where will people escape, if a new earthquake happens? And here, I mean a real earthquake, not one of those small quakes that happen four or five times in a year.

After my coat had been left with me in its transparent plastic bag, the employee disappeared once again behind the big washing machines that emitted a strong smell. Despite my increasing curiosity about the forgotten clothes, there was no credible answer. Horrible things, which no one expects, happen to people. It was enough for someone to go into a small, old laundromat and notice all the cramped clothing from years gone by, to know that sad things happen, and happen a lot, even in the normally calm, eastern suburbs.

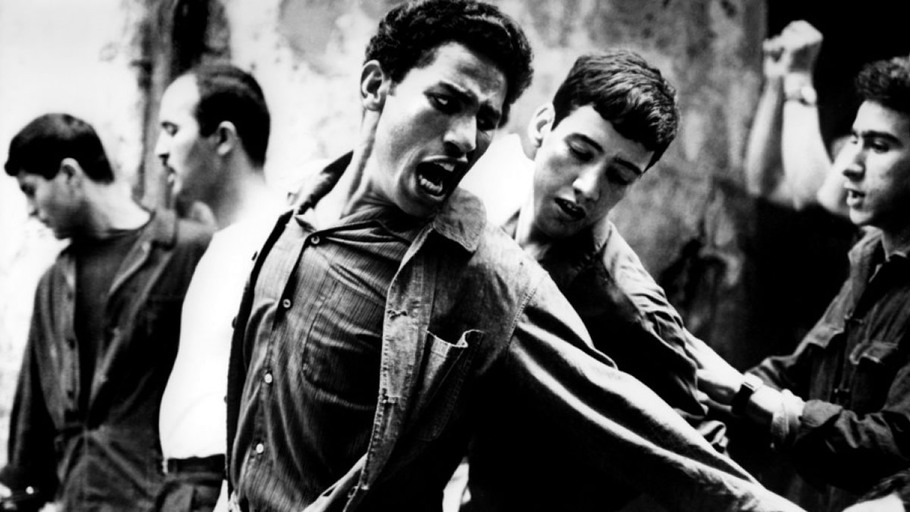

During that same week, I had been returning from university, with all my rolled-up sketches in my bazooka case that causes the lamest comments from passersby. Before I got home, on the school wall near the bus station of the Reghaïa-Algiers Line, I read, “10 dinars, not 20 dinars … these greedy people are stealing from you.” Two days later, on another wall I saw the words: “LA BATAILLE D’ALGER EST TOUJOURS LA [The battle of Algiers continues].” That same evening as I was frying fish fingers and potatoes for dinner, I thought to myself, soon there will be a revolution in Reghaïa.

Mom called me from my sister’s home in Tipaza, just to check on me. It was a very short phone call. Before I ended it, I wanted to tell her: Stay where you are. Don’t come back. A revolution will start here. But I didn’t. I ate a second orange before brushing my teeth, and sleeping.

I could hear the muffled noises from behind the washing machines and the movement of the employees behind them. Holding my coat, I peered through the glass door outside. The rain had become heavier, and darkness had fallen. The whole shop was gloomy. I felt like I was inside one of those apartments I had read about. The small apartments of the bourgeois cluttered with furniture, where families live their whole lives on the verge of suffocating. When the earthquake comes, everything crumbles. I looked at the poster of Building 15 and at all of the old, forgotten clothes. I imagined for a moment I would find my grandfather’s photo there in the laundry, and the other forgotten and misplaced things that had been lost in the earthquake.

Then this idea crossed my mind: What if the laundromat employees were collecting these clothes and other things for the people who will start a revolution in Reghaïa, and it is the employees providing the insurgents with all they will need? When I was about to leave the shop, I heard the employee’s voice once more. He had come out from the back and pointed at the forgotten, old clothes.

“Did you know,” he said, “that these people come when the seasons change … they bring their laundry and forget about it … we don’t know why … Dad used to say that they either went to the sea and drowned, or went into winter and never came out.”

On May 21, 2003, the Zemmouri eathquake, which struck along the coast of Algeria, 50km east of Algiers, had the same 6.8 magnitude as Morocco’s September 2023 earthquake.