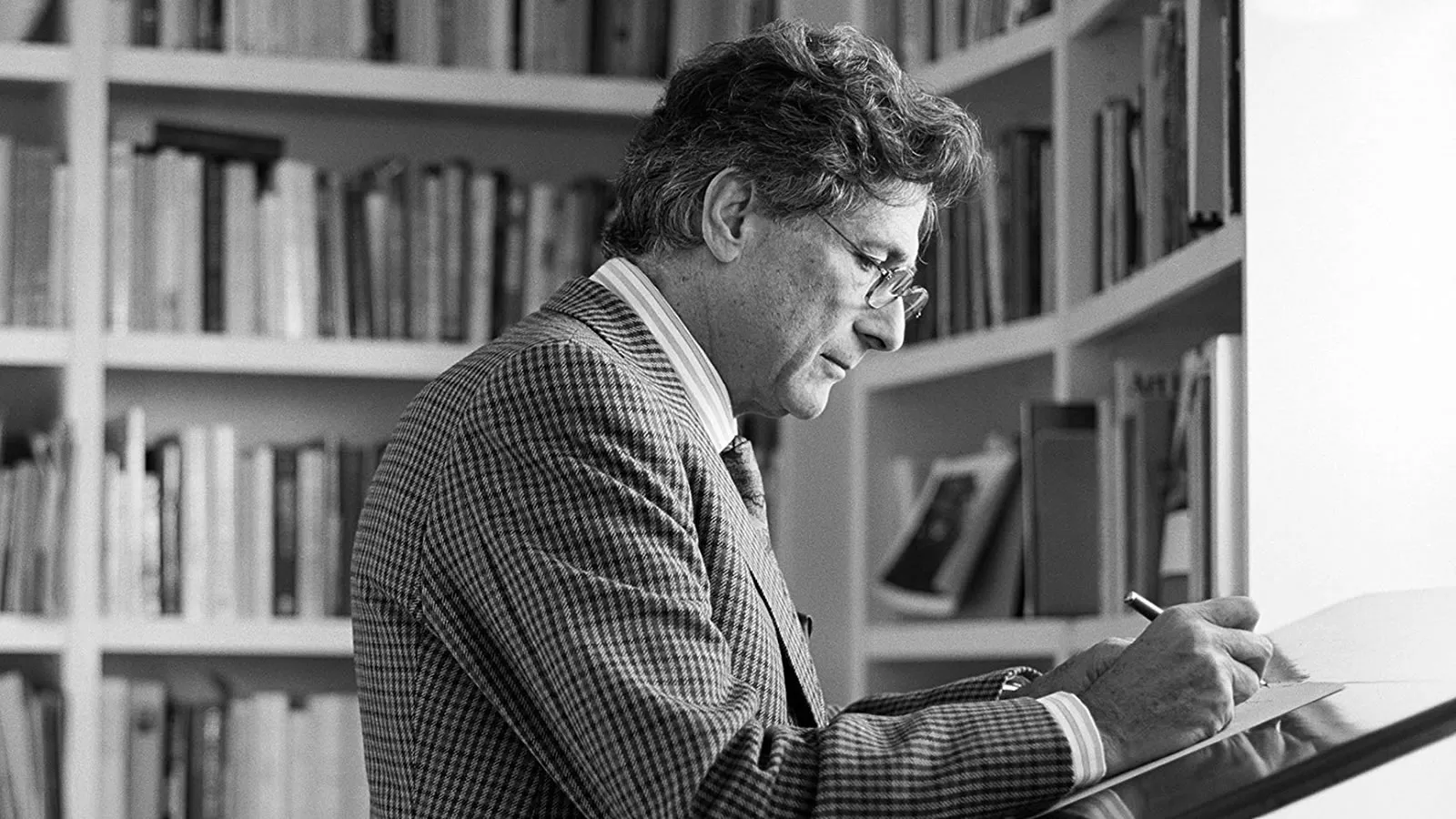

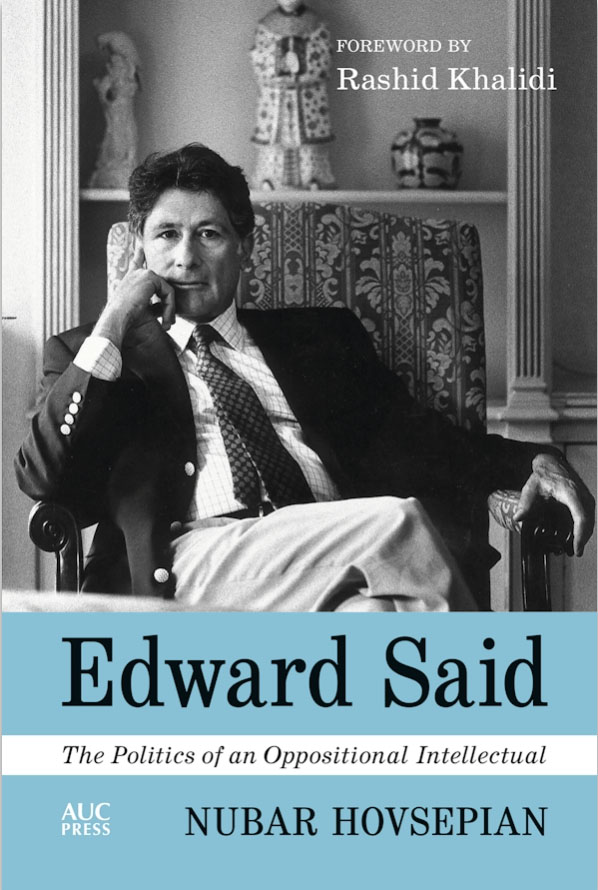

Edward Said reminds us of the power of oppositional intellectuals at a time when Palestine is generating unprecedented sympathy and more grassroots solidarity than ever.

Edward Said: The Politics of an Oppositional Intellectual, by Nubar Hovsepian

AUC Press 2025

IBAN 9781649031761

Edward Said used to say he was the “last Jewish intellectual.” Perhaps it is more accurate to consider Said, a Christian Arab, the last Jewish humanist — an even rarer species today, especially in the tradition of Adorno he claimed as his own. But intellectual or humanist, Palestinian or Jewish (or “Jewish Palestinian,” as he once described himself to Israeli journalist Ari Shavit), Said reminded us of the importance and possibility of taking up the mantle of “oppositional intellectual.” This is the term that guides Nubar Hovsepian’s deeply felt and engaging political biography of his good friend, Edward Said: The Politics of an Oppositional Intellectual (American University in Cairo Press, 2025).

Hovsepian, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Chapman University, approaches this biography through an exploration of Said’s humanism — one of his most deeply held convictions, yet one that has not received adequate attention to date — asking how it informed his broader political project. It is a question with which Hovesepian is intimately familiar, as he participated in Said’s political life as a friend, fellow traveler, and confidant for almost thirty years. An Armenian born in Egypt, who spent his politically and intellectually formative years in Beirut, becoming a part of the Palestinian struggle before settling in the United States as a fellow academic, Hovsepian saw first-hand how Said’s humanism and political thought were at his core, along with his suspicion of state authority and universalist outlook.

As Rashid Khalidi reminds us in his poignant preface, Hovsepian is positioned better than most of Said’s colleagues to make this argument, for he is the only one of Said’s closest circle still with us. He possesses a unique vantage point from which to explore how Said’s travels as a diaspora-based intellectual — an “out of place” Palestinian at that — lived a deep attachment to Palestine.

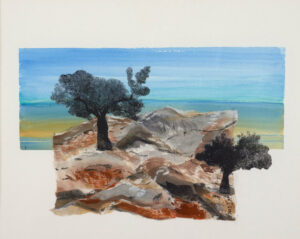

Fierce, eloquent, and fearless — perhaps Edward Said was the last Jewish prophet as well. His was a voice, a life, and a praxis that several generations of young progressive Arab and Jewish intellectuals and academics looked towards as a beacon or model when too many of our own had joined the empire, embraced neoconservatism or insipid neoliberalism, and become comfortably at home with whiteness, power, and inhumanity. Hovsepian points to Said’s writing in Reflections on Exile, where he describes the condition of exile as one that “‘jealously insists on his or her right to refuse to belong,’ or as Theodor Adorno says with grave irony, ‘It is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home.’ In this sense, Said is arguing for a ‘borderless homeland.’” In the end, Said could not return home, not just because it remains occupied, but because unhomeliness continues to dominate the human condition.

We still teach Said’s most famous books, especially Orientalism and Culture and Imperialism, but they arose out of very specific political conjunctures, without knowledge of which his writing’s full force cannot be experienced or understood. Hovsepian recalls his own first trip to Palestine, in 1993, when Said was awarded an honorary doctorate at Birzeit University. In his brief acceptance remarks, “Said insisted that our discourse must project the universal principles of equality, justice, and freedom — predicated on truth-telling. In this connection, one addresses truth to the people whose task it is to unmask the crimes of those in power. It is precisely this sentiment that Amílcar Cabral addresses in his speech ‘Tell no lies, Claim no easy victories.’” Hovsepian’s alignment of Said with Cabral (wondering why Said himself didn’t connect more directly with the Guinea-Bissau independence leader and radical pan-Africanist), along with famed Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, highlights his ability to see the global connectivity of Said with other brilliant activist writers and intellectuals. In doing so, he reminds us of the very real stakes of postcolonial writing — Cabral was assassinated in 1973, wa Thiong’o imprisoned in 1977, giving their writings a sense of urgency and directedness not always available with other members of the founding generation of “postcolonial studies,” such as Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.

Hovsepian situates Said along with Cabral, wa Thiong’o, and Noam Chomsky as “quintessential oppositional intellectuals,” whose lives and work “challenge systems of authority and domination.” They are, he argues, the embodiment of Gramsci’s organic intellectual, joined by similar figures such as his dear friends Eqbal Ahmad and Mahmoud Darwish. These voices are counterposed to “native informants,” such as Fouad Ajami and Kanaan Makiyya; “servants of power” including neocons and warmongers like Samuel Huntington and Bernard Lewis, who cheerleaded every opportunity for war on Arabs and Muslims; and the allegedly “morally anguished” fence sitters, from Albert Camus to Michael Walzer (although when it comes to Palestine, the list grows exponentially), who enable systemic violence while decrying its impact. Against all these, oppositional intellectuals not only remain defiant but also, through their creative and scholarly output, provide the epistemic blueprint for resistance, diagnosing weaknesses in the armor of hegemony and coercion and offering pathways to solidarity.

When Said asked to be “allowed” to be the last Jewish intellectual in a 1988 debate sponsored by Tikkun magazine, he was reminding the audience of their roots. Too few, tragically, would embrace the sense of out-of-placeness that defined his own life (and served as the title of his 1999 memoir) once Zionism offered them a way “home.” It was, Hovsepian shows, a response Said could never come to terms with, and helps account for his late friendship and collaboration with Israeli pianist Daniel Barenboim, with whom he created the East-West Divan Orchestra.

It is fitting that Said directly took up the mantle of Adorno and his colleagues among critical theory’s founding generation — for his part, the Israel-ambivalent Foucault declared that his late discovery of the Frankfurt School likely prevented him from becoming a mere acolyte rather than traveling along his own, if parallel and sometimes intersecting, paths. But representing a still colonized and violated people, Said did not have the luxury or even possibility to remain above the fray, in the “Grand Hotel Abyss” (as Georg Lukács derisively referred to the school), creating theory as the only remaining form of praxis. His path was closer to that of Angela Davis, Adorno’s brilliant late-career student, whose decision to return home to join the Black liberation struggle caused him such consternation. But even there, Said remained unique, “the non-national national who chose to witness and represent the narrative of the Palestinian people.”

There was, and remains, no “clean” way to work on Palestine. Yet Said’s role was not with the gun, or in the office on the front lines like Ghassan Kanafani, whose work he so admired and quoted in his most powerful writing on Palestine. He was, first and foremost, an intellectual, explaining in a 1996 j’accuse against the Oslo peace process in the newspaper al-Hayat that:

Our tragedy is that as a people and culture we have not liberated ourselves from a crude model of power, forgetting that knowledge, information, and consent are more important than brute force and policemen. The only way to begin the change is to… change the battlefield from the street to the mind.

Speaking out, speaking truth to all sorts and intensities of power, and refusing to accept ideological constructions were the battlefields where he could do the most damage, wreaking havoc on carefully constructed discourses of superiority and self-victimization. “The struggle is not only against Israeli and Arab tyranny and injustice,” Said would continue, “it is for our right as a people to move into the modern world, away from fear, the ignorance and superstition of backward-looking religion, and the basic injustice of dispossession and disenfranchisement. For those of us who speak and write, our fundamental issue is the right of free expression (and not who won the Israeli elections), which no appeals to security, military emergency, or national unity can continue to abrogate.”

The fact that these words hold as true today as when Said wrote them in 2001 remind us of his brilliant prescience, something Hovsepian well captures in his biography. Indeed, Edward Said succeeds, particularly for those of us who came of age under Said’s tutelage, whether personally or through his writings, and especially if one was fortunate enough to know, interact, and even study with him, because it reminds us of the level of commitment and dedication behind his seemingly easy brilliance and nonchalant charisma, and the sheer force of personality and epistemological power they together produced. It’s hard to imagine the recent Columbia University administration’s auto da fé of the university’s reputation and integrity occurring while Said held court in his large, book-lined office in Philosophy Hall. It’s even hard — not impossible, but conceptually irreconcilable — to imagine Israel prosecuting a full-on genocide while he was alive to narrate it.

We are now, one generation removed from Edward Said’s untimely passing, in a very different world, and Edward Said reminds us both of the power of oppositional intellectuals but also that we can’t recreate the conditions that gave Said such cultural as well as political and intellectual power, but must find ways to navigate the ones in which we find ourselves. Palestine is generating unprecedented sympathy and more grassroots solidarity than ever, at a moment when a global necropolitical order is enabling the most extreme Israeli violence as never before, when “servants of power,” as Hovsepian terms them, can directly wield it in ever more damaging ways. He offers “a measured and educated guide to Said’s political engagements and contributions,” but the impact is much more than that modest goal for those who read the book with the right effort.

Is there room for humanism today? Edward Said can’t answer that question; it can only remind us what a full-throated humanism should look like: a focus on the most marginalized and exceptioned, but in the name of a common, universal idea of human solidarity. Post humanists and anti-humanists, AI and animal intelligence might have taken the avant-garde of theory, but they do almost nothing to advance the cause of actual human beings. Said as the last humanist is even more troubling than Said as the last Jewish intellectual, but neither intellectual type functions very well in a time of monsters, even if both remain equally necessary.

So how did Edward Said become a humanist? Hovsepian argues that the core works that defined his political praxis — most prominently Orientalism, The Question of Palestine, and Covering Palestine, as well as Culture and Imperialism — are greatly informed and shaped by three variables: his rebirth in 1967 in the context of a maturing Arab American intellectual and political community — what Hovsepian terms “transnational Arab American framework” (116); his decision to affiliate with the PLO and PNC; and his emerging understanding of resistance that was informed by the notion of “effort.” As he explains:

His essays in the 1980s insist that the critic and activist must intervene in the politics of representation, particularly with reference to the struggle over Palestine… This role is not divorced from society; rather, it is embedded in the effort to create communities of resistance and solidarity. These efforts, as noted earlier in this chapter, inform the principles of the peace and justice movement that seeks to end systems of domination by ushering in what Said calls ‘coexistence among human communities.’ In effect, Said’s humanism is not abstract; rather, he calls for direct and active political engagement in seeking peace and reconciliation between adversaries.

How much more relevant an essay could be today is hard to imagine. And yet it is increasingly difficult to maintain a Saidian humanism when Israel — with US and European support — has gotten away with bombing hospitals, schools, and humanitarian aid shelters, and starved an entire population. The criminal actions of a UN member state have, in the space of two years, virtually destroyed international humanitarian law in a way that similar actions by states and para-state groups as diverse as Russia, the Sudanese Rapid Support Forces, and Myanmar haven’t precisely because Israel has long claimed and been described as a “liberal” and “Western” state — an “outpost of civilization against barbarism,” as Herzl infamously claimed it would be in his Der Judenstaat. An overriding concern for humanity seems far beyond where we are today, reaching a level that not only defies description but demands comparison with the worst atrocities humans have committed in recent memory.

Even as many critics, such as Nasser Abourahme or Ilan Pappé, argue that the level of violence unleashed in Gaza indicates a final death spasm of Zionism and with it Israel, this seems highly unlikely, and it’s highly doubtful to me that Said would have shared such a hope. Israel is not French Algeria, Vietnam, or Afrikaner South Africa. Unlike Algeria, there is simply no conceivable way to imagine Israeli Jews being pushed out of the country, nor is there a way to imagine the balance of power, or demographic balance, shifting soon to the point where the Israeli state and people would be held accountable to any degree. However difficult, it seems we are left with Said’s call to forge a praxic humanism that can defeat the murderous violence, not just of the Israeli state and its ideology, supported by the majority of Israeli Jews, but of an end stage capitalism that succors Israeli extremism and makes it both necessary and inevitable for the functioning of the global system in its present form (it’s not for nothing that Israel is deeply implicated in other recent genocidal campaigns, from Azerbaijan’s ethnic cleansing of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh, to the UAE’s, Egypt’s, and Saudi Arabia’s support for the Sudanese Rapid Support Force’s genocidal killing spree across Darfur).

Israel was literally made for this moment in world history. A Eurocolonial outpost of barbarism – and yes, any country born of settler colonialism, racialized nationalism, and mass ethnic cleansing (which together always culminate in genocide) is barbaric in any meaningful sense of the term – against what most human beings would imagine to be civilized human interaction, long functioning as a primary enforcer and capacitor for US empire, is once again called upon to unleash a level of violence that will help bury a now superfluous and indeed inconvenient international rules and law-based order. We do not yet have the conceptual and theoretical, never mind praxic, tools to grasp an entire world in a state of exception, where inequality and concentration of power, and deployment of surveillance and violence globally and within countries, is so deep and pervasive that resistance is far from achieving the efficacy necessary to stop the violence, much less bring the downfall of the system, as the Arab uprising so famously called for fifteen years ago now. Said, like Adorno before him, at least offered the chance for intellectuals to “unsettle the narrative structures that undergird domination” wherever it continues to reign.

Edward Said was, it becomes clear by the end of this biography, first and foremost an epistemologist — both studying and creating the structures and pathways to knowing the world and finding our way through its violence towards a better future. But he was also a musician with words — not a lyricist, but a contrapuntal composer whose political thought was symphonically rooted. In that same interview with Ari Shavit with which I began this essay, Said declares, “When you think about Jew and Palestinian not separately, but as part of a symphony, there is something magnificently imposing about it. A very rich, also very tragic, also in many ways desperate history of extremes . . . that is yet to receive its due.” This sentiment was powerful enough for Homi Bhabha to use it to begin his essay mourning the “dread untimeliness” of his friend’s passing. Hovsepian finds another quote to highlight the profound epistemological harmonies Said was always trying to compose: “And what is critical consciousness at bottom if an unstoppable predilection for alternatives?” from Said’s defining “Traveling Theory” essay. Twenty-three years after his death, early in a new and already frightening century, Said remains a singular prophet, a symphonist, and an exemplar for everyone struggling for a world based on peace, justice, and mutual recognition. This book will prove indispensable for continuing that struggle.