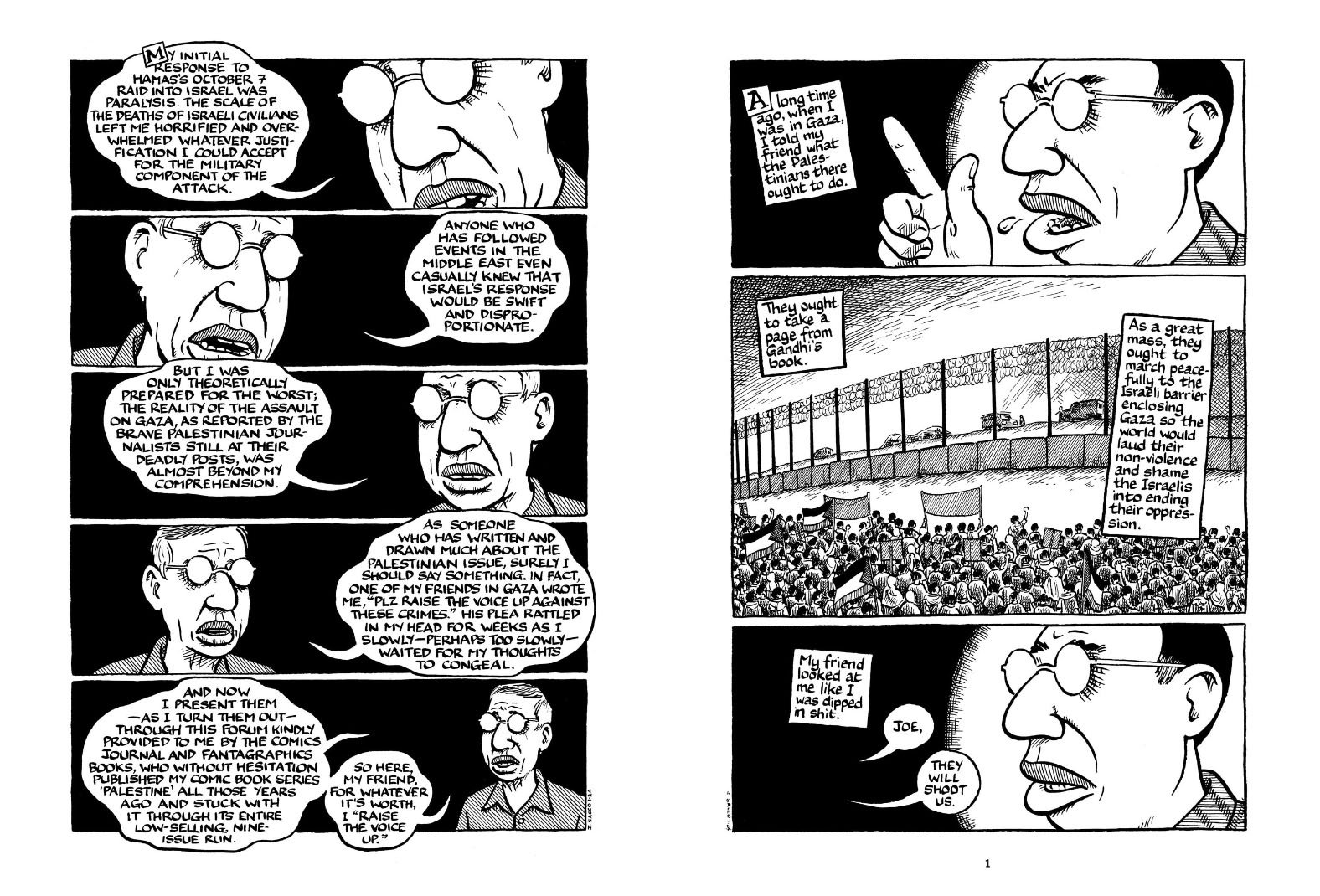

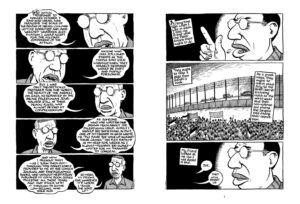

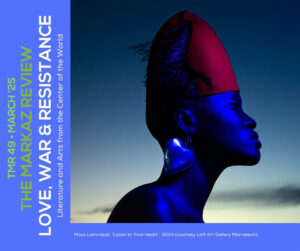

Maltese American graphic artist Joe Sacco discusses the destruction of Gaza following his new book War on Gaza, drawing on his distinctive graphic storytelling to reflect on the dramatic developments in the Gaza Strip since October 7, 2023. First published as a column on The Comics Journal website, the illustrations were released in book form by Fantagraphics in December.

For me, this is a war of annihilation against the Palestinians in Gaza.

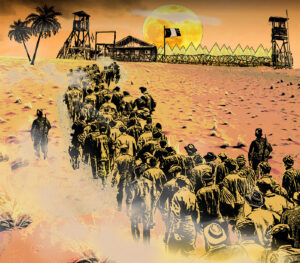

After the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023, the cartoonist was deeply shocked and knew that Israel’s response would be brutal. However, as he recounts, he could never have imagined the sheer scale of destruction. For Sacco, it is unequivocally clear that Israel’s warfare in Gaza has reached genocidal proportions. When we spoke, he said, “More than 43,000 Palestinians in Gaza have already been killed, and many more are likely still buried under the rubble. Hospitals, schools, universities, and infrastructure — practically everything that makes a place livable — have been destroyed. For me, this is a war of annihilation against the Palestinians in Gaza.”

Sacco has been galvanized by war before, having researched and then drawn comics in response on World War I, the Vietnam War and Gaza 1956.

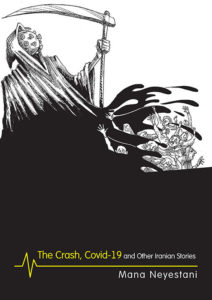

Blending critique with dark humor, the Maltese and American cartoonist/journalist takes sharp aim at the U.S. government in War on Gaza, accusing the former Biden administration of complicity in the genocide. Known for his in-depth graphic reportage and previous work on Palestine, Sacco was forced to work from afar this time. “Like other artists or writers, I see writing and drawing as a form of thinking — you start, and suddenly the ideas begin to flow,” Sacco said. “At first, it was challenging because I don’t particularly enjoy writing opinion pieces. I prefer reportage, but in this case, I had no other choice.” Access to the Gaza Strip remains barred to international journalists, while the Committee to Protect Journalists reports that Israel has killed 187 Palestinian and Lebanese media workers, and imprisoned another 86, since the war began 19 months ago.

The birth of comic journalism

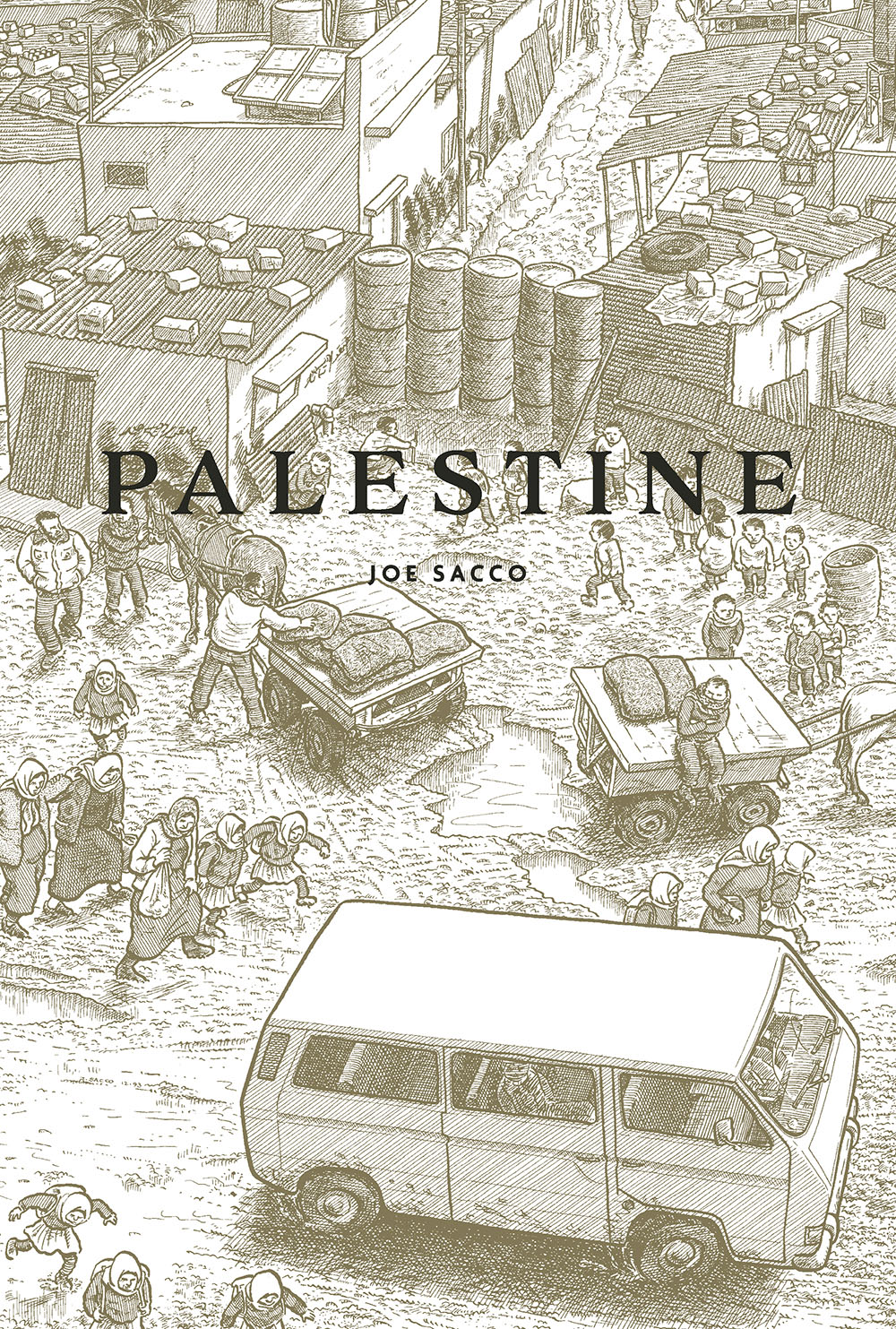

It has been over 30 years since Sacco traveled to Palestine for the first time to report on the political situation there. At the time, his use of the comic medium for journalism was unconventional, and perhaps still is for many. The individual chapters of his first comic were also published by Fantagraphics in the 1990s, later compiled into a book titled Palestine. This work is widely regarded as the birth of a new genre, so-called “comic journalism.” The current war in Gaza has sparked renewed interest in Joe Sacco’s graphic work, prompting Fantagraphics to release a new edition of Palestine, alongside the Swiss publisher Edition Moderne, which reissued the work in German under the title Palästina.

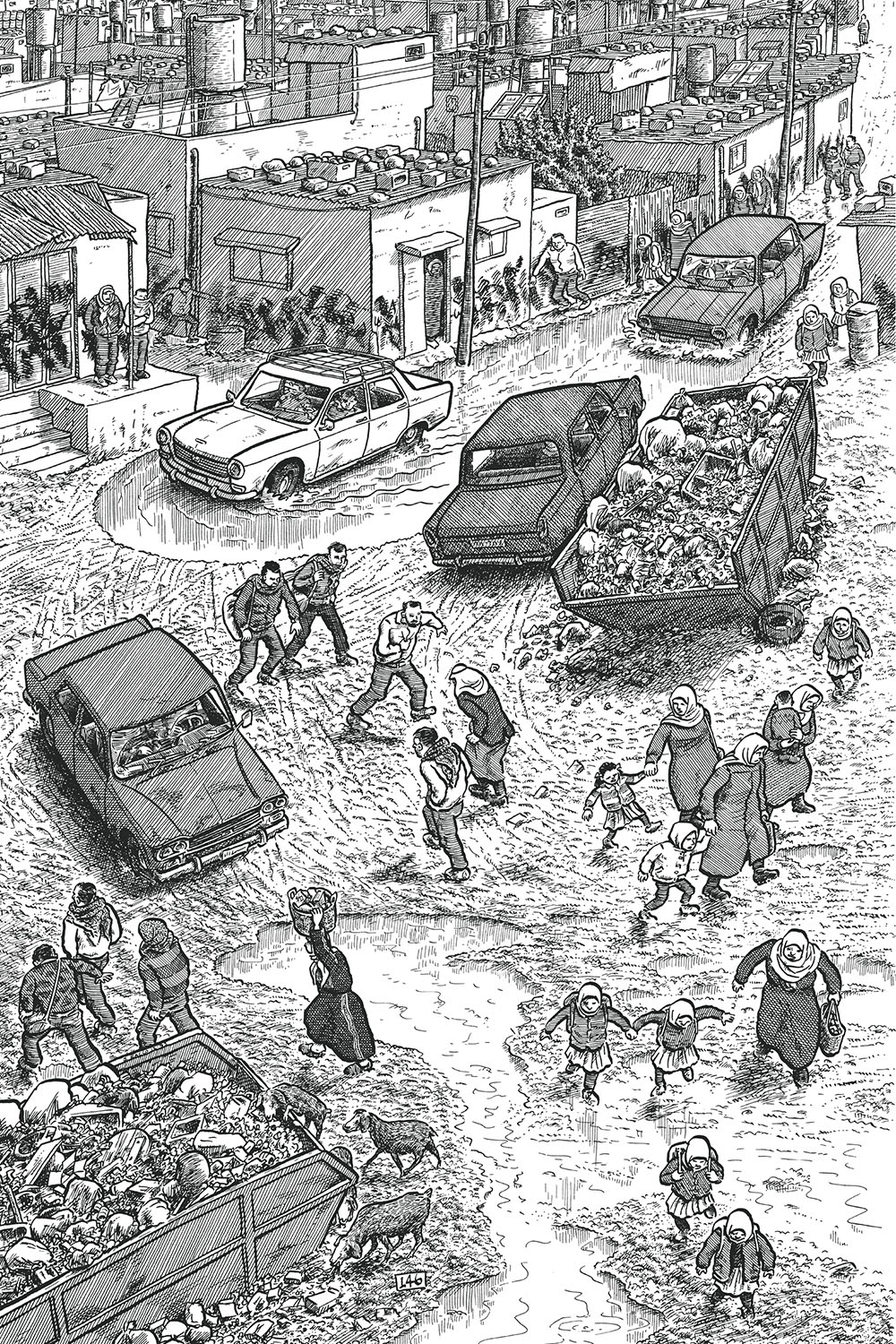

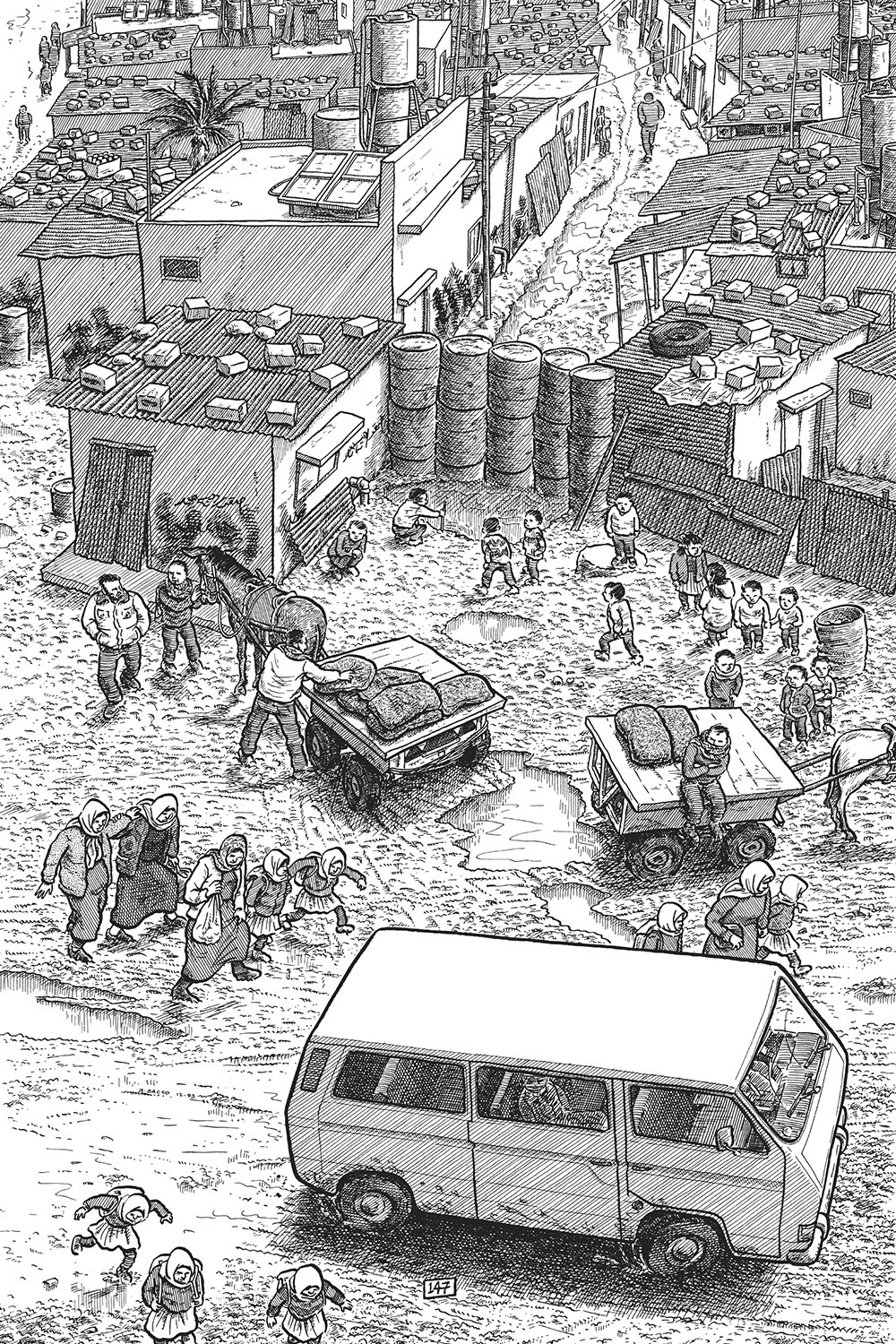

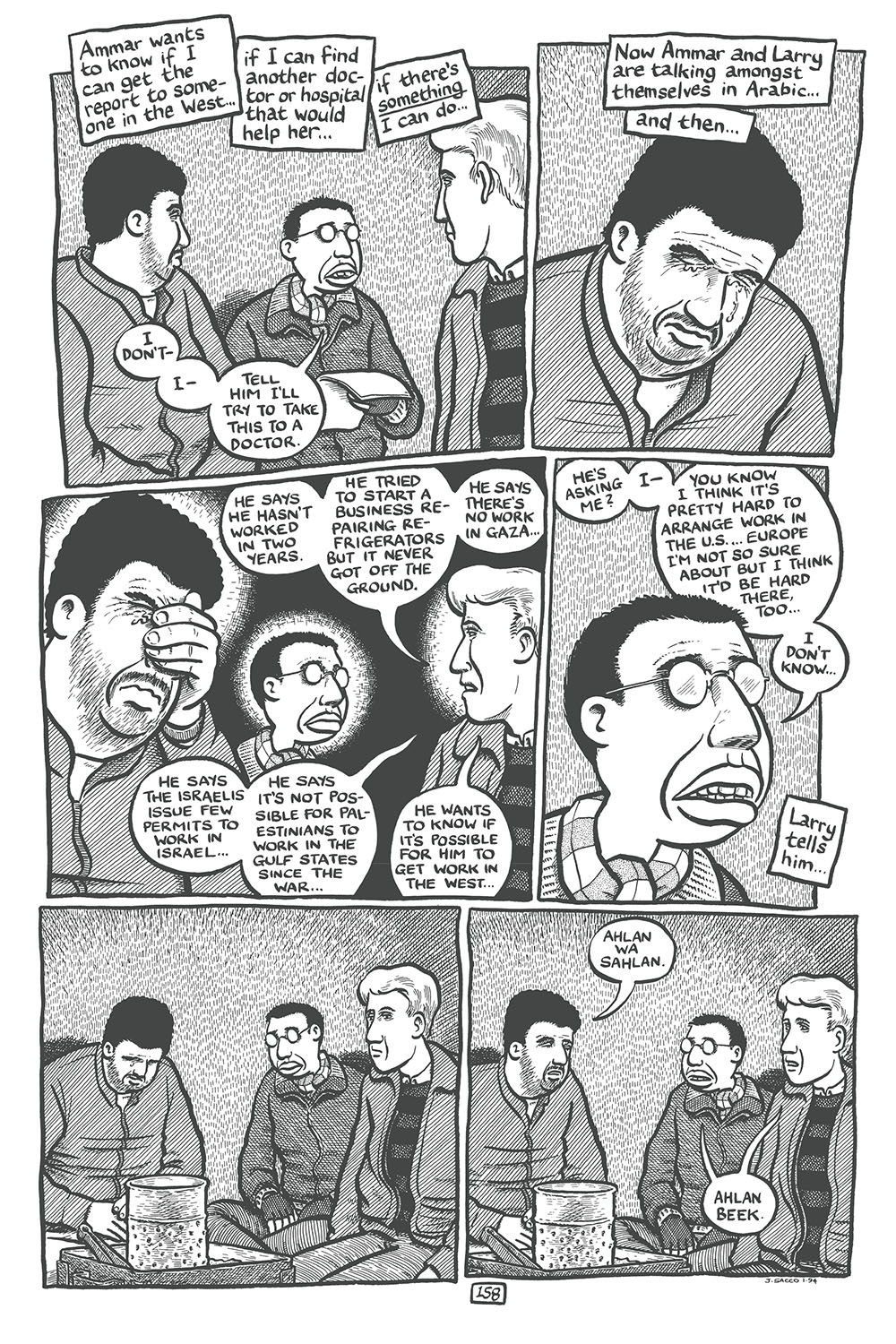

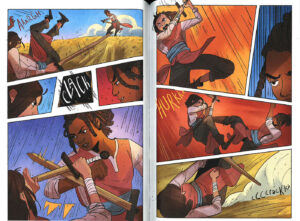

Sacco’s comics are characterized by clear yet dynamic line work, created in the traditional style with pencil, paper, and ink, just as he did when he first began. The process of finishing a book usually takes him years, reflecting his commitment to detailed, in-depth work. Not a single stroke seems randomly placed, giving the reader a precise sense of the surroundings in which the reporter finds himself, whether it’s Jerusalem, Gaza, or Tel Aviv. “I’ve been drawing cartoons since I was a child, but I studied journalism. My original goal was to write newspaper reports,” he recalls. However, after graduation, that plan didn’t unfold as he had imagined. “Since I didn’t want to give up my passion for drawing, it was a natural process for me to convey my reports through the comic medium.”

In his previous works, Sacco addressed themes that remain central to this day: the Israeli occupation, the destruction of Palestinian homes, detentions, and torture. These issues continue to be present in the reports of human rights organizations and on social media.

Gaza: between history and devastation

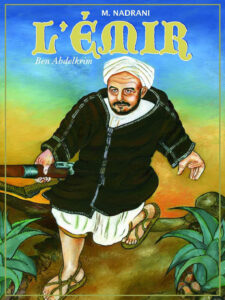

In addition to his first graphic novel, Palestine, and War on Gaza, Sacco released another comic book in which he journalistically explored the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Between November 2002 and March 2003, he traveled to Gaza to learn more about the massacre in Khan Yunis on November 3, 1956, during which, according to UN reports, 275 Palestinian civilians were killed by Israeli forces. As part of this journey, he interviewed witnesses to the incident, which had occurred nearly 50 years earlier. This led to the publication of Footnotes in Gaza in 2009.

Sacco doesn’t simply recount the reports of those he interviews; he compares them, highlights similarities and contradictions, and sheds light on the dangers of oral history. “Sometimes you hear things that you find troubling or that contradict each other, but it’s important to report these things, nonetheless. You have to be honest about your reporting,” Sacco notes.

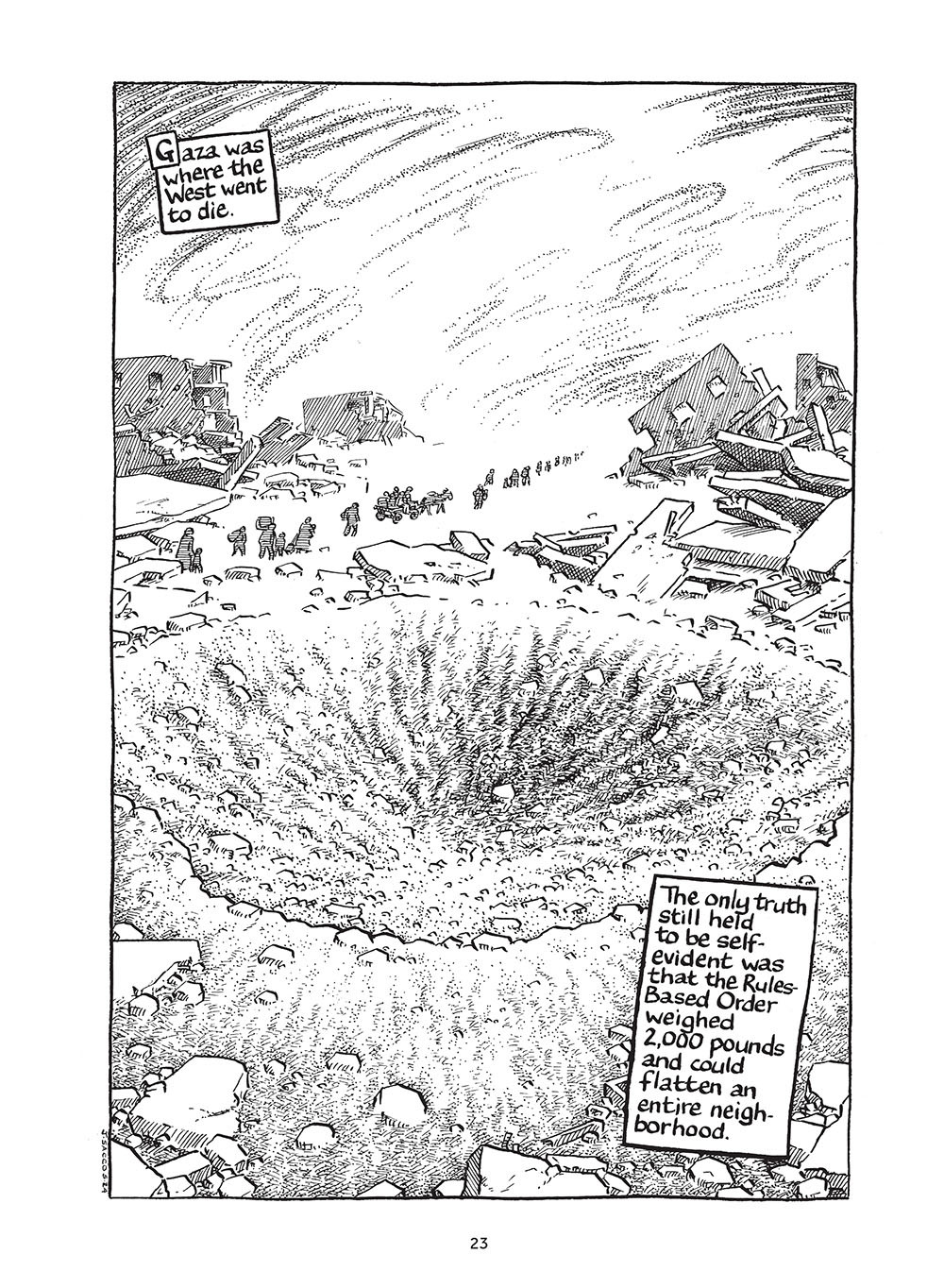

Both Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza are rich, multilayered works. The process of conducting research, carrying out and documenting interviews, and creating the comic itself is an extraordinarily intricate one. In his latest book, the once-familiar streets of Gaza — streets the journalist wandered through in the ‘90s and 2000s, vividly captured in his earlier graphic novels — are no longer present. Instead, they have been replaced by scenes of bomb craters and debris, for the Gaza Strip that the reporter once knew has been erased, replaced largely by rubble and devastation.

Sacco’s conclusion in War on Gaza is harsh. “Gaza was where the West went to die,” he writes. The liberal enlightenment of the West is a façade, a falsehood that became apparent the moment the pulverization of the Gaza Strip was almost universally accepted, and even acclaimed by some Hamas critics. Following the arrest of students protesting Israel’s onslaught, calling for a ceasefire, Sacco concluded that western liberals cared neither about Jews nor Palestinians, as in the last months since the war started, many Jewish protesters around the world have also been detained for opposing the war. He powerfully covers these scenes in War on Gaza. The cartoonist shows that Jewish protesters are branded “self-hating Jews” for standing against the bloodshed in their name. At the heart of this failure, Sacco, says in our interview, is German memory culture, a concept the cartoonist, who once lived in Berlin, once held in high regard.

“The narrative coming out of Germany is pathetic — morally reprehensible, all couched in terms of morality. That’s the problem. When I was living in Berlin, I was always very impressed with how my friends would talk about the Nazi past. They would speak about it reflectively, with shame and disgust…But that shouldn’t lead to supporting the State of Israel no matter what it does. You’ve got to look at Israel as a nation-state and judge its actions as a nation-state. I think Germany basically has its guilt, and it’s using the Palestinians, in a way, as its penance — allowing this to happen to them and arming Israel to do this to the Palestinians. This is just wrong. It’s just as bad as what’s going on in America.”

Sacco shared that he continues working on projects focusing on Palestine, driven by the profound sense that there is still a vital need for such work. He spoke about his friend from Gaza, Abed, a fixer who assists journalists with logistical support, local knowledge, and connections, who managed to flee to Egypt. Abed, who played a key role in Footnotes in Gaza, is a reminder of the deep personal connections that shape Sacco’s storytelling. Sacco was asked by his friend not to remain silent about the horrors unfolding in Gaza, a request that has become a powerful motivator for Sacco’s continued commitment.

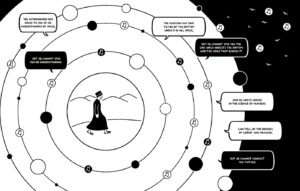

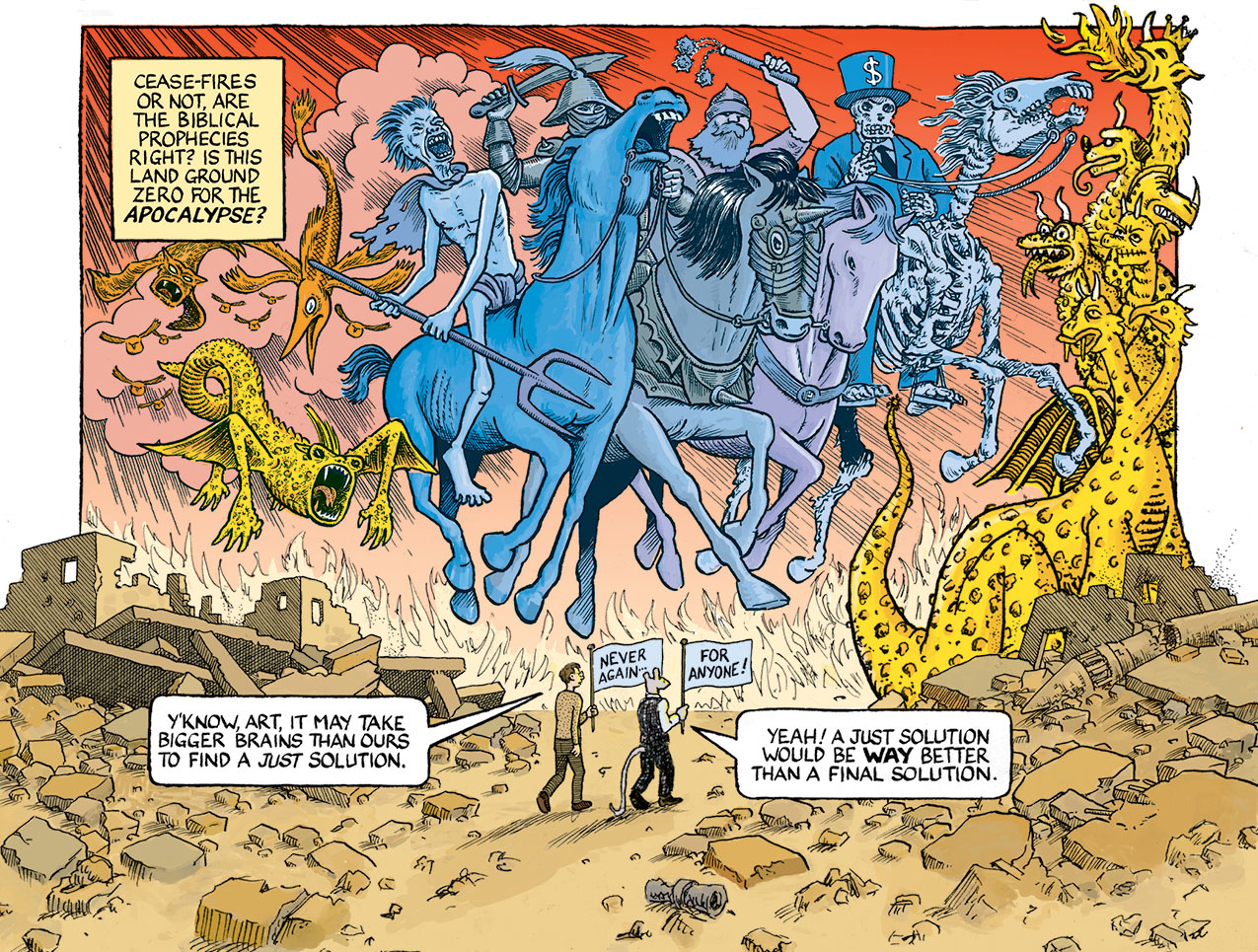

“Never Again and Again” – A collaboration with Art Spiegelman

In the February 27th issue of the New York Review of Books, one will find a rare collaboration between Joe Sacco and Art Spiegelman, two of the most influential figures in political comics. Spiegelman, best known for Maus, the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic memoir in which he recounts his father’s survival of the Holocaust, has long used comics to explore questions of memory, trauma, and Jewish identity. Their joint comic, titled “Never Again and Again,” spans just three pages but delivers meditations of the two artists on the war on Gaza and on the meaning of the lessons of the Holocaust — a term Spiegelman openly rejects in the piece, noting that its Greek origin implies a form of sacrificial offering, rather than the systematic murder of millions, including members of his own family.

Both artists appear in the comic, rendered in their respective visual styles — Spiegelman as a mouse, just as he is also drawn in Maus, and Sacco in his familiar, self-drawn likeness. They stand amid the ruins of Gaza, a landscape of utter devastation. With characteristic irony, they suggest that it may take “bigger brains” than those of two cartoonists to find a just solution for Israel-Palestine. And yet, one lesson from the post-Holocaust — or rather, post-Shoah — era remains painfully clear. In the final panel, each of them holds a white flag, bearing the words “Never Again…,” the other “For Anyone!” Hence, the pledge of “Never Again” is not only a call to remember and prevent the repetition of the Nazi genocide but a universal warning against all forms of mass violence and oppression.