Play the Game, the latest novel by French-Algerian author Fatima Daas, is a coming-of-age story that explores what it means to grow up queer and Muslim in France. Accompanied by a small band of ride-or-dies, her young protagonist Kayden navigates the tribulations of adolescence, starting with the first day of lycée.

“Tenth graders, class six!”

In the schoolyard, Principal Baudot is hoarsely yelling into a microphone: every class and assigned teacher, and the first and last name of every student.

Class Six follows Mrs. Garance Fontaine.

She doesn’t say hello. She simply gestures to say, “this way to the classroom.” She walks briskly and the students have to hustle so they don’t lose sight of her. They don’t know these high school hallways yet.

Kayden and her friends, Nelly and Djenna, follow the crowd.

Mrs. Fontaine isn’t the kind of teacher to make jokes. She says the strict minimum. The students are allowed to pick their seats by affinity. But if she determines that it’s not working, there will be a permanent seating plan put in place until the end of the year. Five minutes after the second bell is five minutes too late, no point knocking on the door. If you miss a lesson, it’s on you to catch up and come prepared for the next class. Meaning that if Mrs. Fontaine assigns homework, you better not show up empty-handed. If your homework isn’t submitted on the assigned date, you lose one point for every day you’re late. And don’t assume she’ll be absent whenever there’s a national strike. Mrs. Fontaine doesn’t go on strike.

Once she’s explained the rules, Mrs. Fontaine quickly does roll call from her desk. She doesn’t bother with last names.

Maïssane

Nelly

Sephora

Djenna

Alim

The students barely have time to say “yes” or “present,” and she’s already on to the next one.

Fairouz

Irène

Abdelilah

Lucas

Simon

Romane

Taoufik

“It’s pronounced Tooo… You don’t say the a,” says Taoufik.

Mrs. Fontaine scribbles something on her list.

“Noted for next time.”

She finishes roll call and stands up.

“I’d like you all to write your names on a piece of paper, fold it in half, and place it on your desk. Bring it to class every day for at least two weeks so I can memorize your names.”

She sits back down.

Kayden carefully writes her name on a white piece of paper, which she folds in half and displays so it’s visible from the blackboard. Mrs. Fontaine notices. She looks at her, reads her name. Her lips move silently. KAYDEN. Kayden immediately looks down, and fiddles with a pen grabbed at random from her pencil case.

Mrs. Fontaine stands again, now holding up a double-sided questionnaire to be attentively filled out and placed on her desk when the bell rings. She hands out the forms herself. No one is to stand up during class so as to avoid “disruptions.”

Most of the time, Mrs. Fontaine will remain seated. She is not the energetic schoolteacher who walks through the rows, enthusiastically waving her arms to encourage all to participate. A few months from now, the class will have been categorized according to: the gifted, the sleepers, and the troublemakers, the latter of whom will, if needed, be kicked out of class without preamble. No skin off her nose; Mrs. Fontaine isn’t a social worker.

Kayden studies the questionnaire, which has multiple sections, like the ones distributed in middle school. First, student information, first name, last name, gender, date of birth, address, telephone number, then mother and father’s names, professions, contact info. Already, she’s annoyed. She debates not reading the rest, or maybe she’ll just check boxes at random, boom, done. She glances at Mrs. Fontaine, who meets her gaze. Kayden flips the paper over. She feels obliged to do something. She begins by crossing out the part about the father. She doesn’t check male or female, and stares at the form for a few minutes, blasé.

What do you like to do in your free time?

Kayden notes, “write,” and sets down her pen.

What do you enjoy about school?

Djenna writes: Oussani (the monitor)’s smile, my girlfriends who wait for me at the gate, people who make jokes, when we debate societal issues in class, when we get a nice surprise when a teacher is absent and we’re let out early, eating in the cafeteria (a chicken panini with Algerian sauce).

To her left, Nelly is happily listing her hobbies: first, track and field, followed by, sleeping in, listening to music (rap, R&B, reggaeton), hanging out with friends, going to the movies when she has money, being picked first for teams in PE.

Kayden, Nelly, and Djenna hand in their questionnaires. They meet up with Sami in front of the school. He’s sitting on a bench, a cigarette in his mouth.

“It’s wild how you’re never cold. What are you wearing?” Djenna asks him.

“It’s called style,” responds Sami, who’s wearing a yellow crop top under a black and white Adidas jacket.

When they get to the pizzeria, there are already other students from the high school ordering. No time to waste; Sami has to be back at 2 p.m. He’s on the vocational track, hairstyling. Regular high schoolers and vocational ones never start their first day at the same time. The latter have their classes on the right side of the school, the former on the left.

The group sits at the most isolated table, for some privacy. Nelly takes the order. She suggests they get two pizzas. It’s 50% off for the second, so she does the math.

“€5 for one pizza and the second half off. If we don’t get drinks, we’re good.”

Kayden thinks, “What’s pizza without Coke?” She has €2 in her pocket. Her mother gave her the money that morning so she could take the bus and get to school faster. Kayden didn’t use it. She rationalized to herself — what’s the point for just two stops?

Sami takes out two €2 coins and one €1 coin. Djenna €3, Nelly €4, and Kayden €2.

“€14,” says Nelly. “We definitely have enough for a 2-liter bottle of Coke. Everyone put in at least €3.”

Sami puts his €5 down and squeezes Kayden’s hand under the table. Djenna grabs the money and goes to the counter to order two pizzas, an Indienne and a tartiflette.

Kayden is thinking about Mrs. Fontaine, their new teacher.

Kayden jumps into the shower once her sister Shadi comes out. Then she throws on black skinny jeans, a white tank top, and a checkered shirt. She grabs the Sharks that Shadi gave her, and that she’s been wearing all summer. She can’t imagine wearing anything other than TNs now. Shadi even thought to get her one size bigger.

After brushing her teeth twice, for that sparkling smile, Kayden starts on her hair. She plugs the Baby Bliss in the outlet beside the mirror. As the device heats up, she separates her hair vertically using a comb, and sprays on some straightening oil. The button’s stopped blinking, which means the straightener has reached 190 degrees. Kayden starts with the most difficult part, the hair at the nape of her neck. She slides the straightener down the first segment of hair, root to tip.

Her mother walks by the bathroom, sees Kayden doing her hair, and enters the living room with a sigh. Shadi’s at the table sipping hot chocolate.

Until recently, Shadi used to straighten her hair too. And when you straighten your hair, it’s every day. God forbid someone realizes that you don’t “really” have straight hair. It would take Shadi, whose hair almost reaches her butt, over an hour. If and when she was struggling, Kayden would drop everything and help her run the straightener over her roots and tips. Shadi would even bring the Baby Bliss to school, tucked into her purse, so she could restraighten her hair at lunch.

The point wasn’t to look like Ophelia or Manon, two girls in her class. She just wanted people to stop touching her hair. She just wanted people to leave her the hell alone. It’s just hair…

Kayden massages her scalp to get a bit of volume. In the living room, her mother is repeating the same anecdote she’s been telling for ten years.

“I knew this woman who never showed her husband her real hair. She would straighten it all the time, just like you and your sister. When she took a shower, she wouldn’t come out of the bathroom until her hair was dry and perfectly straight. Every. Last. Strand. Whenever it rained, and also when it didn’t rain, she always had an umbrella on her, just in case.”

Shadi ignores her mother. She’s watching Snap stories posted by her friends Coumba and Sekou. Aïsha keeps talking.

“This woman was afraid that her husband wouldn’t love her, that he would stop loving her. She was ashamed of her hair, even in front of him. She wanted to look like the blonde women in the magazines. Then they had a daughter, and she started to straighten the girl’s hair too, once she turned five. Miskina.”

Shadi loses patience: “Wesh, mama. Leave her alone. She’ll get over it.”

Aïsha retorts that she can tell it’s an addiction, that the girl doesn’t stop even when she burns her forehead or her finger, that “it” is going to make her late, and it’s only the first week of school.

Shadi looks at her in confusion. “Say what?”

Aïsha responds, “The straightener! Instead of focusing on school… Plus it’s ugly, all that heat damage. She’s going to burn her hair to a crisp one day. When you have kids, you’ll understand.”

Shadi bursts out laughing. “You really are a drama queen. Enough with your Algerian soap operas. You’re becoming a caricature, wallah.”

Kayden comes out of the bathroom, and rushes to grab her Puma backpack. Tenth grade… She wonders, How am I going to survive this year?

She couldn’t care less about arriving late. She’s hurrying for her mother, to let her know, “Don’t worry. We’re on the same side. I don’t want to show up late. I’m aware of how lucky I am to go to school, to have access to education, to knowledge.”

But in truth, Kayden is faking.

This Sunday, her mother wasn’t working. Kayden had prepared her coffee, which she set on the coffee table: a glass mug on which was engraved Every day coffee day, beside the box of white sugar cubes, brand Eco+, bearing the slogan, “Simplement bien!” Simply good!

Usually, Aïsha prepared her coffee herself. One minor detail could ruin everything. Kayden had prudently gone back and forth from the kitchenette area to the sofa for every step of the process to get Aïsha’s approval.

First, unscrew the aluminum Italian espresso pot, which she had done easily enough. The motion transported her back to early childhood, six or seven years old, the mornings before going to school.

“I don’t know why he shuts this thing so tight. No one can ever open it after him. The man is self-absorbed!”

Her mother would say the same thing nearly every morning, when she couldn’t unscrew the espresso pot. The “man” was O., Kayden’s father, who, sprawled on the open futon, would take his time getting up, use the bathroom with the door open, throw on a white undershirt, and finally, nonchalantly, grab the espresso pot and easily unscrew it. Aïsha didn’t find that funny at all. She had fifteen minutes at most before she had to head out for a long day of work.

O. had his ritual. Once Aïsha left, he had his first coffee at home, a second at the local PMU bar, then he checked the mail and returned to the apartment. He would station himself in front of the computer and play solitaire or spider solitaire for hours. He only ever worked for short periods at a time because he couldn’t stand having “someone on my back.” It always ended in a fight with the boss and the same speech when he came home. “So-and-so thinks I’m an idiot, well forget that! Time to open my own business…”

Aïsha handled all the bills, the rent, the responsibilities.

Once she reached adolescence, Kayden had made a promise to herself, which came back to her, yet again, as she returned to the sofa after placing a scoop of ground coffee in the central funnel, careful not to pack it down: never be anything like her father.

That night, Aïsha settled in on the futon, and turned on the television for her show. Shadi emerged from the bedroom to do a few dance moves to the opening credits for Taxi Majnoun as her mom watched, entertained. Before returning to their room, she reminded her little sister to aim high. “Don’t let them make you believe that you’re a hmara.”

Later, between peeling the carrots and the potatoes, Aïsha signed Kayden’s school forms.

At the school entrance, written on the outer wall in capital letters, there are three words. Words that kids memorize early on, and which adorn public buildings in France: Liberté Égalité Fraternité. The motto of the French Republic. France, le pays des droits de l’Homme. Translated literally: the nation of the rights of man.

Kayden had never understood that last part. How could “man” possibly encapsulate everyone and anyone?

The high school had been demolished and rebuilt. The building was imposing and inside, all the furniture looked fake, like Legos in a Play Do décor meant for paper figurines.

Kayden takes her ID card out of her backpack and quickly flashes it to the monitor stationed in front of the gate. Oussani welcomes each student with a big smile, a friendly jibe, and a “have a good day.”

Leaning against the wall, chewing gum in her mouth, Kayden watches the students streaming out of her friend Sami’s classroom. There are some fifteen kids on the vocational hairstyling track. Some of them are rushing, others are still putting away their things, laughing at their teacher’s jokes. He seems like a fun teacher, thinks Kayden.

She starts counting the number of girls versus boys but loses track when Sami comes out the door. As soon as their eyes meet, both of them smile. Sami gives her four kisses on the cheek, longer than the usual pecks, calling her “mon poussin,” my sweet pea.

They slowly make their way down the corridor, heading for Kayden’s side of the school and a set of gray metallic chairs screwed to the floor, where they can chat for a bit.

“I think I have a crush,” Sami gushes.

Kayden laughs. “Oh yeah?! You fall in love every other day…”

Sami promises her that this time it’s true, he really does feel something. Holding out his phone, he tells her, “Look. His name is Ibrahim. But everyone calls him Ibra. Check out his photos.”

“What am I looking for?” asks Kayden.

“Pretty gay, no?”

Kayden smiles, pensive. “How can you possibly know?”

But Sami’s sure. He tells her about Ibra’s photos on social media, about his gentle/broken vibe, how he dresses, how he doesn’t laugh at the other boys’ jokes, how nice he is. Different from everyone else. Sami says that he can sense these things. No way he’s wrong. Kayden responds that Ibrahim is handsome and that they would make a very nice couple.

“Listen,” says Sami. “Here’s the thing. There are four boys in the class. It’s simple. Two of them either made a mistake when they signed up for hairstyling, or they don’t know that they’re queer yet. But they are.” He pauses. “Then there’s Ibra, of course. And we both know. So we already have something in common. Right?”

Kayden doesn’t say anything. She finds Sami’s confidence comforting, loves how he finds his words so easily. She stands up to walk him to his next class. Sami stops in the bathroom to check that his hair and his makeup are still in place. A ritual Kayden could observe day in, day out.

Students are coming in and out of classrooms, teachers too, including Mrs. Fontaine. Kayden sees her approaching and their eyes meet. As Mrs. Fontaine walks by, Kayden says hello first, softly. The teacher nods and keeps walking. When Sami comes out of the bathroom, Kayden points to her teacher. Djenna’s already told Sami all about her, about how strict she is.

Mrs. Fontaine doubles back and asks Kayden if she can talk to her for a minute, as she scrutinizes Sami’s nail polish. She continues once he walks away.

“So I read your questionnaire. It was pretty short. You only answered one question.

Tell me why?”

Kayden feels her muscles contracting. She hadn’t prepared for this. She tries to find the words buried deep in her throat, but they don’t come out. Mrs. Fontaine is staring at her from behind her glasses.

“I can’t just make up your parents’ contact info, your ranking last year, or your professional goals…”

“All right, all right,” stammers Kayden as she scratches her head.

Mrs. Fontaine insists, “I want to understand. You crossed out some of the questions. You left a bunch blank. No other student did that.”

Kayden is looking down, back hunched. She can’t tell her teacher that her questionnaire is lame, that it’s ill adapted.

“Can you look at me when I’m speaking to you? It would really be a shame to leave the questions unanswered. These are things I need to know. Do you understand that?”

Kayden quickly looks up, then away again, fists clenched. Summoning her courage, she meets her teacher’s eyes.

“May I go now please?”

Mrs. Fontaine, surprised, insists.

“Hang on, Kayden. You like to write? You want to write? Can we talk about that?”

Kayden runs off, the words jammed in her throat.

TEXT TO REPLACE THE CLASS QUESTIONNAIRE

My name is Kayden. My friends call me Kay. Don’t worry, it’s not short for caïd or racaille. It’s just to go faster. It’s efficient — Kay. People often tell me that I have a boy’s name. Sami, my best friend, who you saw with me in the hallway, sometimes gets taken for a girl. He doesn’t care. I think he finds it flattering, actually.

I like my name. Kayden can go either way, boy, girl.

I was born on October 23. I consider myself half Libra, half Scorpio. My sister and my mother are both Scorpio. I love Scorpios. My older sister’s name is Shadi. We share a bedroom.

My mother is named Aïsha. She sleeps in the living room on a secondhand futon that she got for €50. It’s gray, but most of the time she drapes it with a multicolored cover. My dream is that one day, she’ll have her own bedroom.

Not a bedroom attached to a kitchenette.

Not a bedroom where you can still smell food bought at the bargain grocery store, or the Camembert stinking in the fridge, or the pipes. No, an actual bedroom with a door that closes and curtains on the windows, a pastel bedroom without a rainbow-colored sofa covering so bright it makes you want to vomit. With a bedside table, a dressing table, and a wardrobe with lots of pretty clothes hanging on solid hangers from Hangar World, not the thirty-hangars-for-€2 from the marché that break as soon as you hang a jacket that’s slightly too heavy.

And no futon. A true queen-size bed.

My mother works a lot, but she always finds time for us.

There’s no man of the house, so I can’t give you my father’s contact info. Sorry… I can give you the number of my uncle Fouad, just in case. He’s really nice. He’s the one who would pick up my middle school report cards, when my mom was working nights.

Otherwise, I didn’t get great grades in middle school, just average, but I was pretty good in French class.

I don’t know what I want to do when I’m older. Sometimes I think about becoming a teacher. Though there are lots of drawbacks. I don’t really feel like grading students, handing out As and Fs, making fun of them in the teachers’ lounge and rattling off all their vocab mistakes, or deciding they’re ignorant because they don’t know the date of the storming of the Bastille or the history of Louis XVI.

I can already picture it: me telling these kids how lucky they are to have access to free public schooling, that it’s not the same in Africa… Sounds awful, right?

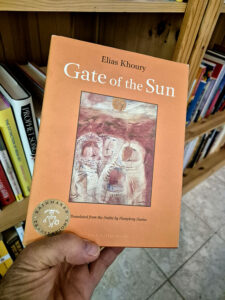

I’m not sure whether I like school. But I do like to read, especially novels, sometimes poetry, and also essays, when the author doesn’t use fancy words. We all know they could write more simply.

During my free time, I write, though I also write when I don’t have time. I have to. I write letters that I’ve never sent. I wrote when Soraya, a girl in my elementary school, moved away without warning. I write short stories, profiles, and little texts in my notebook. I don’t know what I would do without my writing.

Good? I think I’ve answered all your questions.

Excerpt from Jouer le jeu (Éditions de l’Olivier, 2025), published with permission from Le Monte-charge culturel.