Select Other Languages French.

Art Basel Qatar marks perhaps the first time that an art fair has become central to the culture-as-infrastructure policy of a modern state.

“This is not your usual art fair,” remarked the chairperson of Qatar Museums Authority, Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa al Thani, during the preview days of Art Basel’s inaugural edition in Qatar. It’s the Swiss art fair company’s fifth outpost, after Basel, Miami Beach, Hong Kong, and more recently Paris. Sheikha al-Mayassa was referring to specifics of the Qatar edition, like its smaller show (fewer than ninety galleries), a slower approach based on solo presentations curated by the fair’s artistic director, Egyptian artist Wael Shawky, and the nontraditional venues spread across the Msheireb Cultural Forum “M7” and Doha Design District. Sheikha Al-Mayassa’s QMA oversees a dozen institutions, some of them yet to come.

It is not unheard of for fairs to receive government support to raise their profiles and enhance their credibility, but the situation in the Gulf is far more intricate. Two art fairs in the UAE, Art Dubai and Abu Dhabi Art, both founded in 2007, benefited from close public-private partnerships or were directly spearheaded by government agencies (Abu Dhabi Art was acquired by Frieze, the competitor of Art Basel and will re-launch as Frieze Abu Dhabi in 2026); however Art Basel Qatar is perhaps the first time that an art fair has become one of the central nodes in the culture-as-infrastructure policy of a modern state. In the words of Sheikha Al-Mayassa, from the opening speech of Art Basel Qatar last week, the fair is not only a marketplace, but a catalyst for the state’s cultural vision.

This vision translates not as a single top-down narrative of soft power or dominance, but rather a half-century old, multigenerational project that has yet to find its final form. The story begins with the founding of the National Museum of Qatar in 1975, right after independence, by Emir Khalifa bin Hamad al Thani, grandfather of the current emir; it continues with the previous emir, Hamad bin Khalifa al Thani, commissioning the design of the Museum of Islamic Art in 1999 by Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei, the launch of Education City around the same time by his consort, Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, and the creation of the Qatar Museums Authority in 2005, since chaired by his daughter Al-Mayassa.

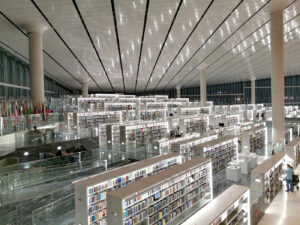

The third generation, led by the current Emir Tamim bin Hamad al Thani and his sister Al-Mayassa, undertook one of the most ambitious culture-as-statecraft projects in the world. Mathaf, the first and largest museum of Arab modern and contemporary art, opened in 2010 under the Qatar Museums Authority, and new ventures have been added since then, such as the new National Museum of Qatar, designed by Jean Nouvel and opened in 2019, the Art Mill and Lusail Museums, both under construction and slated to open in 2030, and supported by extensive infrastructure, including Fire Station’s residency program launched in 2015 and the Arts Intensive Study Program, led by Wael Shawky, inaugurated last year, not to mention numerous public art commissions, and the M7 in Msheireb, one of the venues of Art Basel Qatar.

To be sure, Qatar’s culture-as-infrastructure extends far beyond art, and also encompasses archaeological heritage, international cultural diplomacy at home and abroad, education, and sports (Art Basel’s partners in the country are the Qatar Sports Investments and QC+, the commercial arm of the QMA). Therefore, it is no surprise that the press conference of Art Basel was held at the symbolic National Museum of Qatar, blurring the lines between enterprise and government: “This moment is about more than an art fair, it represents our nation’s transformation from an economy of hydrocarbons to an economy of knowledge, connecting the vast creative potential of this region with the world.” It is also a moment of deep transformation for art fairs, amidst economic and political instability in the West, seeking new places within cultural ecosystems.

Although the fair has been likened by Art Basel and collectors alike to a biennial where the art is for sale, it is not a biennial in either scope or structure (as if biennials weren’t marketplaces anyway). Yes, Wael Shawky’s concept for the fair — “Becoming” — allows for enough space of ambiguity to introduce a breadth of ideas, from personal identity to material transformation, from cartographic repositioning to historical form, but Art Basel Qatar is still pretty much an art fair in spite of its boothless open spaces, one that would greatly benefit from a traditional fair venue (the fair is slated to move to a more permanent home on Al Maha island, when the complex is completed in 2030 or so). And the concept of one artist presentation per gallery has indeed made the fair more compact and allowed, as promised, for richer conversations and encounters.

At first sight, upon entering Gallery 1 at the M7, you find yourself looking at the kind of art that you would see in any art fair, with major western, mostly male, artists, meant for the deepest pockets of the 0,001%, such as Pablo Picasso, Neo-Rauch, Donald Judd, George Baselitz or Jean-Michel Basquiat, and that perhaps would command little attention from the nascent art institutions in the region that are seeking to complete or complement regional collections. But again, we’re not in a biennial. There are a few (female) surprises however, such as David Zwirner’s booth with the spectacular paintings of the great Marlene Dumas, one of the most important living painters, who grew up as a white woman in South Africa during apartheid, and whose 2010 painting “Figure in a Landscape” is breathtaking and achingly reminds us of the division walls in Palestine.

Rachel Whiteread is also present — she is one of Britain’s most prominent sculptors and belongs to the Young British Artists generation that rose in the 1990s but, in my mind, is the only artist in the group that remains culturally relevant. She was presented by Rome’s Lorcan O’Neill, with one of her iconic shelf sculptures from 1998 and the resin piece “Untitled (Luce Verde)” (2020) that in its deceiving translucency suggests a moment of transition into the unknown.

At Lisson Gallery, there is an exquisite presentation of works made between 1969 and 2017 by Olga de Amaral, the Colombian artist and weaver, who has been engaged for decades with the indigenous ontologies and artistic techniques of the Andean region. Her work “Cesta Lunar 56” (1994), a grandiose installation beyond weaving and sculpture, involving gesso, acrylic paint, Japanese paper, and gold leaf, is in dialogue both with the baskets of the Yanomami, a tribe in Venezuela, and also with the place of theories of space and structure in western minimalism. In a conversation with gallery partner Louise Hayward, she said it was the gallery’s interest to foster an exchange between Latin American art and museums of Islamic art in the region, a task that remains incomplete and long overdue.

Another Latin American, Brazilian artist Solange Pessoa, who is one of the country’s most prominent artists, and represented by Mendes Wood MD, a Sao Paulo gallery with presence in four countries, speaks closely to the postcolonial, anthropocenic present of the Gulf region in her Solarengas 2 series pigment paintings, where she addresses in particular the imaginaries of the colonial baroque in her native region of Minas Gerais, now an industrial mining region.

Thai artist Pinaree Sanpitak’s sculptures from the series Balancing Act (2024), a different set of which I’ve seen recently in Sri Lanka’s Colomboscope, were presented by Lelong and Ames Yavuz of Singapore and Sydney, one of the most exciting contemporary art galleries, representing a diverse roster of practices from the broader Middle East, Southeast Asia, and indigenous Australian artists.

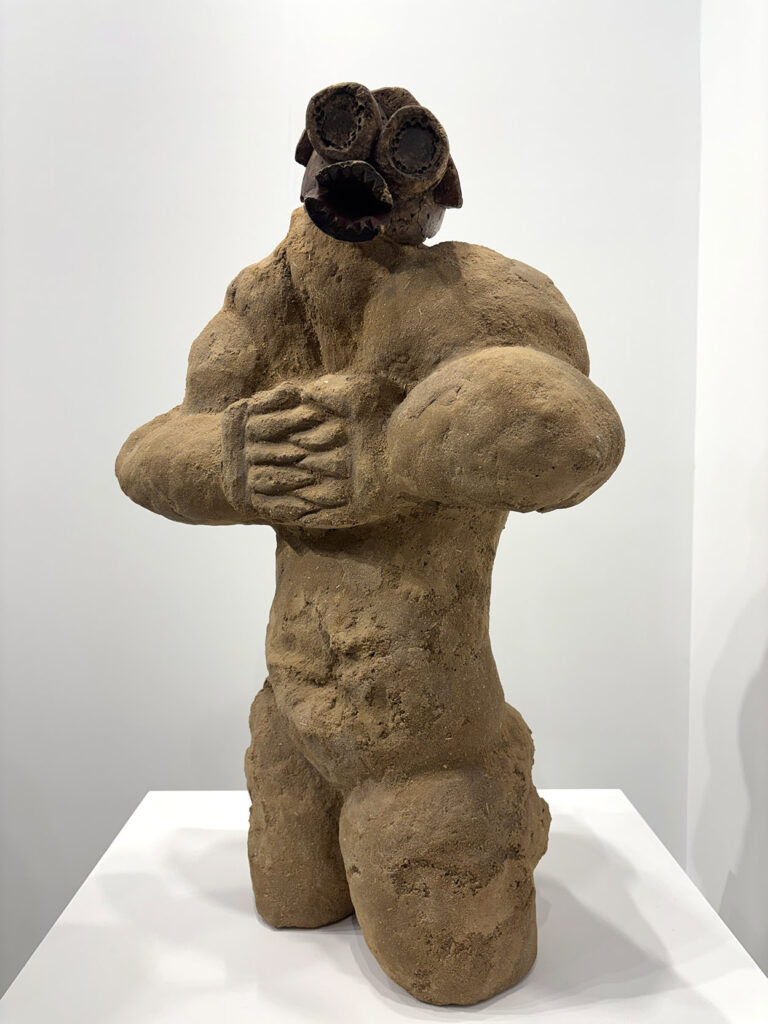

But the real stars of Art Basel Qatar are the artists from the wider Middle East, whose careers have taken shape concurrently with the rise of the Gulf as an artistic ecosystem, and the galleries, local or otherwise, that have nurtured their practices. The first booth you see upon entering the fair is mega-gallery Almine Rech, presenting Lebanese artist Ali Cherri, whose work centers the geographies of violence in the region, with a few sculptures that blur the lines between animal and human, using discarded archaeological material as a reference to colonial exploitation and disfiguration of cultural landscapes. But it is in his diptych “Do I Belong” (2026) that his visual poetry shines — something rare in an art fair — with an isolated fox (that may be alive or dead), asking the question whether we belong to the earth or the heavens.

At Parisian gallery Chantal Crousel, you find works by Mona Hatoum, the most important Palestinian contemporary artist of her generation, and recently reviewed in TMR with recent exhibitions at the Barbican Centre and Museo Nivola. The sculpture “Divide” (2025), a hospital screen replacing the privacy and comfort of a curtain with see-through mesh wire, reminds us of surveillance, institutional violence, and enclosure, not only in Palestine but in refugee camps and through mechanisms of exclusion, imprisonment, and erasure all over the world. I was glad to become acquainted with the work of Palestinian American artist Nida Sinnokrot, and his totemic sculptures Water Witnesses (2020-ongoing), inspired by the collection of Palestinian amulets of Dr. Tawfiq Canaan, ancient deities from the Levant, and the modern infrastructure of water and occupation, represented by European gallery Carlier Gebauer. Vienna’s Galerie Krinzinger, an early believer in the regional art fairs, presented an iconic sculpture by Saudi artist Maha Malluh, “Keep Cool” (2016), which uses air conditioning units as parts of a Rubik cube, pointing humorously at the challenge of energy consumption in the region.

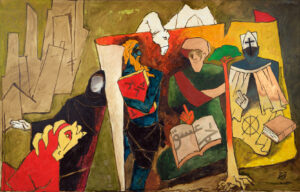

Veteran galleries from the region, in Dubai and Beirut, brought not just artists of renown whose work is recognized and internationally exhibited and collected, but also the accumulated experience of decades of fostering conversations with the wider art world, nurturing collecting publics and advancing critical discourses. At Beirut’s Saleh Barakat Gallery, one of the oldest galleries in the region, founded in 1990, the series of paintings Painting Parakletos (2025), by conceptual artist, thinker, and teacher Walid Sadek, combine an attempt to overcome the historical traps of modernism in painting with an awareness of recent socio-political shifts in Lebanese society that have rendered the aesthetic program of the post-war years obsolete, and sent him searching for new transtemporal conversations between the Greek and Islamic worlds.

Dubai’s Gallery Isabelle showed works from the late Emirati conceptualist Hasan Sharif, one of the very few conceptual artists in the Gulf, dating back to the last years of his life (he passed away in 2016). Another Dubai gallery, Green Art Gallery, originally founded in 1995 as a modern art gallery with roots in Syria but relaunched in 2010 as a contemporary art gallery, brought works by NY-based Iranian artist Maryam Hoseini: a series of compelling panel paintings that depict duration, sequencing, and fragmentation in almost cinematic style.

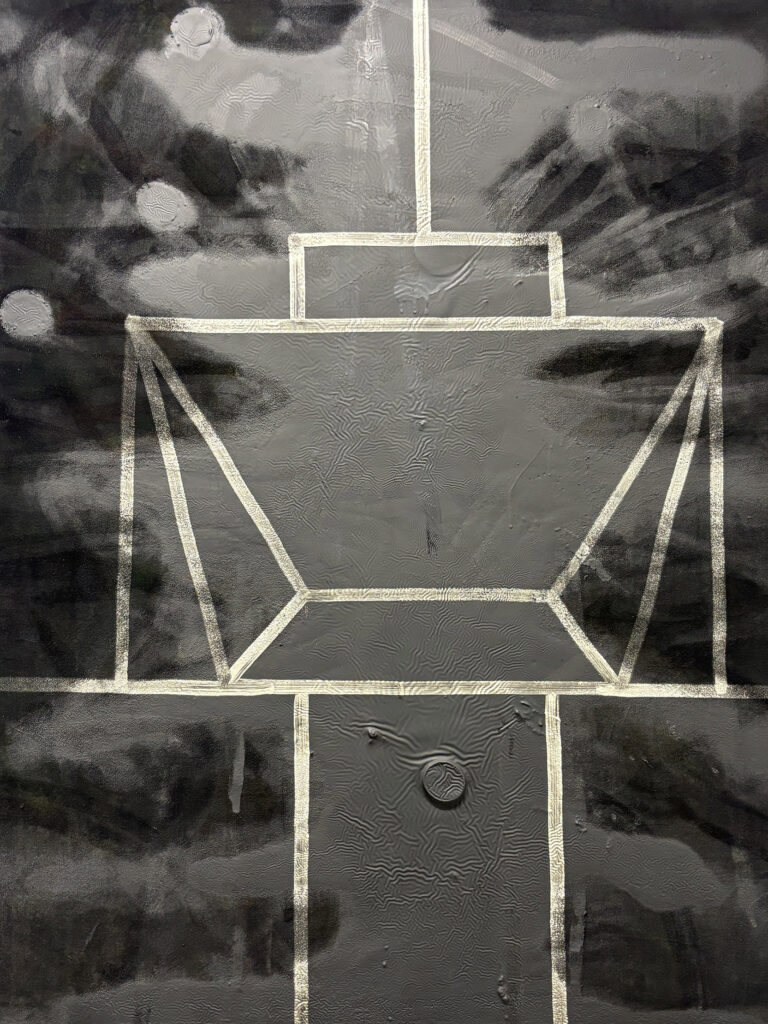

Another Dubai fixture, Carbon 12, a gallery that recently participated in Art Basel Miami Beach for the first time, presented in Doha the work of one of the most exciting young artists from the region: Emirati conceptual painter Sarah Al Mehairi, whose series “Off Centered” sculpturally investigates negative space in painting, and continues her interest in abstraction not as a historical period, but as a processual language embedded in spatial experience.

One hopes that, in future editions of Art Basel Qatar, these regional galleries and artists would be in more prominent, visible locations, and not mere footnotes to the international art world. Furthermore, it feels important here to highlight the decades-long trajectories of these artists and galleries, if only because much of the western coverage of the fair has given the impression that journalists and western dealers were descending upon the Gulf for the first time, even though they have been going to Dubai and Abu Dhabi for almost twenty years, half-ignoring the decades of groundwork that has taken place not only in Qatari institutions, but also by different actors, private and public, in the United Arab Emirates and Lebanon, among other countries — an omission that is a disservice to both Art Basel Qatar and the larger region.

In a conversation with Vincezo de Bellis, the global director of Art Basel fairs, he acknowledged, for instance, the role that Art Dubai played in the growth of the art ecosystem in the region. Whether galleries will land in Doha with physical spaces is a question that, in his opinion, cannot be answered right now. And he is right in the sense that the state of Qatar has chosen to develop new art ecosystems at a slower pace, serving long-term cultural policies that are not defined by immediate market results (the fair did not publish sales reports). But it is also true that the role and impact of art fairs is rapidly changing, and other small countries such as Cyprus, Lithuania, Armenia, and Georgia, with far less financial muscle, are betting on art fairs as catalyzers for their larger cultural ambitions.

In this joint co-production of cultural goals and realities, Qatar might change Art Basel just as much as Art Basel can contribute to the country’s vision. When a fair is not defined by a daily sales report, the traditional media reporting based on best booths (who is the judge?), prices — which I avoided entirely, despite my suspicion that many price lists were out of touch — and celebrity appearances, it needs a different format to describe these complex and entirely novel forms of culture-as-statecraft, and in which the roles of galleries, museums, and fairs are becoming increasingly seamless and corporatized.

There are also aspects of the fair that could use some improvement. Many of the events were completely oversubscribed and curatorially speaking, the presentations of celebrated regional artists Etel Adnan, Simone Fattal, Huguette Caland, and El Anatsui felt tired and lifeless, even though they are quintessential names in the art histories of the Middle East and Africa.

And it would be dishonest not to mention the elephant in the room, namely the conversation about the presence of the Gulf countries in the world of contemporary art. Art Forum’s Pablo Larios has written recently that Gulf states have been embarking on some of the most ambitious feats of state-building seen anywhere in decades, and that this project represents “the most significant reconfiguration of the contemporary arts infrastructure to occur since the integration of the Chinese art scene into the international circuit in the 2000s.”

But these reconfigurations are not timeless political facts. When I reviewed Phaidon’s book Art Cities of the Future (2013), thirteen years ago, many cities, like Beirut, Bogota, Sao Paulo, or Istanbul, were about to emerge as contemporary art capitals but somehow didn’t, and not only because of prolonged internal struggles. The structural conditions of the controlling western centers that defined those futures also changed, and today, we are migrating in different directions, intellectually and artistically. The momentum for Chinese art that Larios mentions passed quite rapidly and its influence waned, so it remains to be seen whether the Gulf will make a lasting impact, which is even more possible now when western institutions are losing not only funding and revenue, but also control of the grand narrative of cosmopolitism.

While of course eroding freedoms and censorship are quintessential topics in cultural reporting, not every exhibition review in Europe or the United States is colored by the grim political present or labeled as state propaganda. But a different bar is applied to Gulf countries, involving a subtle form of racism, wherein every institution is expected to respond to charges of authoritarianism and violence, whereas western institutions themselves are in the hands of international finance, chaired by boards with questionable reputations and often silencing dissent. Larios asks an important question regarding the intricate relationship between those institutions and the Gulf states: “But what does it mean to criticize Gulf states at a moment when ailing western governments and organizations are accepting their capital inflows — through bailouts, private investment, cultural patronage, and direct financial underwriting?”

Back at Art Basel Qatar, a new chapter has begun that might see the transformation of art fairs from an annual trade event to a semi-institutional framework, close to the powers and infrastructure of the state. Do art fairs wield too much power and influence, considering they are not institutions or taste makers? I guess art fairs themselves are changing to suit this new role, adjacent to cultural institutions, government agencies, municipalities, and finance. Observers in the region are nervous about the infrastructure growing much faster than the collecting public, with three art fairs (plus the Riyadh Art Weekend) in a small region, but Art Basel remains confident about the possibilities of growth. A gallery from Latin America sold two major works to institutions, one of them local, so presumably they will be happy to take the sixteen-hour flight again. Perhaps so will many others.

Art Basel Qatar, from 5-7 February 2026, Msheireb Downtown Doha. M7 – Barahat Msheireb – Doha Design District.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)