In a Levantine family, on the island of Leros, an abundance of trees and medicinal plants have the power to heal.

There are as many ways to live with the dead as there are to die alongside the living, thought Aspa Pagóni as she crossed the garden, overgrown with thorns that wounded her bare shins. She ducked beneath the branches of the male terebinth tree, expecting more wild weeds, but nothing had dared grow there. The soil beneath the leaf canopy was covered with hard black drupes — tears that had fallen from the felled female terebinth, formerly a world in itself, separate from the house and the island where Aspa and her brother spoke as they wished, softly or loudly, in the dialect of Leros or in proper Greek. Where they chased cicadas, played shipwrecks among the autumn drupes, and forgot their arguments over who would get the heart of a watermelon. Of that live dome — from which they had watched their grandfather tap resin to be distilled into turpentine — now remained a dry, bodiless stump and a silence broken only by the honking of the island bus, always two times at the twists in the road.

Aspa sat on the stump. She remembered how, also on the first of January, forty-something years before, when she was eight and Thomas was six, her curls got caught in the branches. Thomas cut her hair so that she wouldn’t be kept prisoner all night in the freezing cold. After they had gone inside to drink lemon balm tea, father lowered his newspaper and asked, “Who gave you that boy haircut?” Aspa ran her hand through her hair. It untangled immediately, just like in her nightmares.

“Since you wanted two boys, Marínos, I’d think you’d prefer her like that,” said Mamá, who was making cauliflower au gratin, which Aspa would leave on her plate untouched. Mamá didn’t have any enthusiasm for cooking, children, or husband. Nobody understood why she’d married in the first place. She wasn’t even pregnant back then.

Babá stood. He was tall, thin, with bushy curls. A human stone pine. “Who cut your hair like that?” he asked again.

Aspa whispered, “The ramithiá.”

Babá tossed the newspaper onto his armchair. “Didn’t we say that we would speak more loudly?”

Aspa tried but she couldn’t manage, especially at such moments. She was always afraid that her voice bothered people, whereas Father insisted that, on the contrary, her unintelligible whispers annoyed him.

“The ramithiá took my hair, Babá.”

He corrected her: “The terebinth.”

Aspa looked in the mirror above the old mahogany buffet table. She didn’t want to look like a boy, but she did.

“The other kids call those trees ramithiés and avramithiés.”

“We speak proper Greek, not island dialect,” said Father. “We say ‘terebinth,’ not ‘ramithiá.’”

“Short hair is better,” said Mamá above the storming of the extractor fan. “Boys have a better time.”

When Aspa was eleven, Marínos Pagónis sold a few pieces of land, as well as the vacation apartments that he owned in Leros. With a partner, he bought a hotel in Athens. Subsequently he announced to the children that they were moving to the capitol “so you don’t grow up speaking lérika.” He said the last bit with such disdain that Aspa inferred that the dialect of Leros wasn’t just rural, but also dirty. Mother was happy with the decision. Born in Athens of Peloponnesian parents, she’d never gotten used to the close island atmosphere. Thomas cried. Aspa laughed so she wouldn’t cry. They boxed up all their things. Behind their container and their car, the family boarded the ferry in couples, Father-Thomas, Mother-Aspa. The boat put out to sea, but Aspa’s mind remained fixed on the great ramithiá. “I wish my hair were still tangled in its branches,” she said to the foaming wake that the boat scattered through the Aegean.

They settled into Athens. From that point on, they only went to the island for summer vacation and visits to grandma, who always made them loukoumádhes — although she called those small, round doughnuts langítes instead of loukoumádhes — and she served them with marmalade of gaváfa, a fruit like a big pear on the outside and slimy pink on the inside, which she grew in her garden and which nobody in Athens had ever heard of. Every August Aspa left the island weeping silently and holding a branch of wild lavender, which grandma called lambrá — bright — instead of levánda. Aspa would look backward toward the ramithiés, believing that she could make out their tops over the town of Saint Marina.

She spent time alone with her father only twice in her life. The first was on that ferry in 1986 after her parents’ divorce. Thomas remained on the island with their grandparents for a week longer, but Aspa and Father had to return to Athens for preparation lessons and work, respectively. From that trip — the only one that they ever took alone — Aspa remembered the loud, rhythmic drone of the ferry when it entered the harbor like a monster. She remembered the lights of Patmos and Mykonos in the black night and the potato chips that they ate with cola for dinner. They slept in each other’s arms on the open deck, woke to the sight of Aegina, pedestrian and low in the first light of day. Patmos, Mykonos, and Aegina were recorded in Aspa’s memory as islands that she saw while Babá was alive. That was why she took the airplane when she returned from France decades later, in order not to see them without him. Her life had split into two parts: that which she lived while she still had a father, and that which she carried on afterwards.

The year 1986 was also the last time that Aspa enjoyed Leros. From 1987 onward, Father always brought a girlfriend. Mamá would vacation at the country home of a friend, also divorced, and Aspa preferred to spend summers with the families of her friends. In August 1994, Mamá disappeared with her divorcée friend. She didn’t tell her children about the ovarian cancer until the final days, a few hours before the last nap that gave way to eternal slumber. Two months later, Aspa went to Paris to study. Thomas visited her on a weekend. Even the greengrocer of the quartier understood that they were siblings. They looked alike. They had the same full cheeks, the same round bottoms, the same long eyelashes that fell into their eyes when they got wet. They also had a familiarity, a whispered communication that showed they’d grown up together. When Aspa accompanied Thomas to the airport, she cried so much that she almost couldn’t see him wave to her from the security line. That was how much her eyelashes drooped into her eyes like heavy, wet awnings.

Aspa couldn’t remember how they fell out. It happened just after she got a job working as a landscape architect in France. Some disagreement about the hotel that, by that time, Marínos Pagónis owned fully, as well as an arrogant remark from Thomas: “Go see what the world is like and you’ll run back to us begging for work.” Which Aspa understood as, “You’re not capable of making it outside the family.” All that from a mediocre student who had never left the family environment, whereas Aspa had graduated summa cum laude in Athens, completed her master’s in France with grade Très Bien, and found work afterward without any connections. Her father took her brother’s side in the argument. So Aspa left again for France without replying to Thomas; without quarreling. For the next decade, she retreated into silence, ignoring the ringing telephone that she so wanted to answer, throwing greeting cards and letters into the trash, giving away to friends the gifts that arrived from Greece.

Had she stayed in Athens, she would have had an easy time and a good salary. Perhaps she would have become assistant manager without the responsibilities of an assistant manager. She would have cared for the potted geraniums, the lobby ferns, the bougainvillea in the rooftop pergolas — women’s jobs. She would never have become manager. There was no way that Father would ever appoint a woman to that position, despite the fact that they had inherited their matronymic last name, Pagónis, from a woman forbearer named Pagόna. They’d become Athenians. They’d forgotten the times when the Aegean was ruled by women.

The summer of 2019, Aspa traveled to Greece to visit French friends. She flew directly from Athens to Ikaria. After a few days on the island, she called her father in Leros and asked, “Should I visit?”

“Come, daughter,” he said. “I’m alone.”

That was the second time they were alone. Babá was waiting for her at the quay with open arms. He was fat and round. He didn’t resemble a stone pine anymore. He’d spread his branches like a terebinth, a living shelter, a whole world. They reconciled without apologies and scenes, as families should. They went for walks on the beach of Álinda, beside the leaning tamarisks. They took rides in Babá’s fishing boat. They trimmed the terebinths and gathered the previous year’s hard black drupes, rotten and smelling of hospital and death. At the end of five days Aspa didn’t want to leave the father whom she’d waited years to acquire. She changed her ticket in order to spend another week with him. She thought he would be happy, but instead he shook his newspaper and hid behind it. The same afternoon, while they were in the car on their way to Gurna to watch the sunset, he said that her brother was coming in two days. Father didn’t want tension. Aspa understood. She paid the ticket change fee a second time and left as originally scheduled. On the scala of Saint Marina, she tried to hide her tears. Once aboard, she ascended to the upper deck to find her babá, as if she could hold him near with her eyes. He was pacing the quay, bent at the waist, trying to burn something inside himself. When he saw Aspa, he stopped his pacing for a moment, smiled strangely, and waved. That was the last time she saw him.

The pandemic began the following winter. Babá retired and returned permanently to the island that he had renounced along with its dialect. He wanted to be free from quarantines and masks, to read his newspaper in the garden, to take walks along the sea without being harassed by the police, to write a book about business management. Unfortunately, he found writing difficult and lonely. The guava trees, which his father had brought back from Egypt as saplings and called gaváfa according to Arabic custom, and even the terebinths were not as good company as he had hoped. No beautiful woman crossed his path at the beach, nor dined in his favorite taverna, nor emerged from the sea. Even if she had, he might not have noticed because beauty had been hidden behind masks. His morale fell so much that, afterward, Aspa thought that retirement should have been included as a cause of death along with the other.

His last wish had been to be buried on the island, high up, in the cemetery of Saint Marina. Aspa didn’t go to the funeral, not so much because of the restrictions as out of fear of quarreling with Thomas, who had shouted at her on the phone when Babá fell ill: “This is a serious illness, it’s not a cold! Are you vaccinated?”

“Why are you yelling?”

“I don’t yell at anyone, only you do this to me!”

They ended the call, but Thomas’s shouts remained in Aspa’s ears and soul. She didn’t dare go to her father’s funeral.

As soon as the restrictions were lifted, she sold her gardening business, donated half her things to charities, sent others to Greece, gave up her apartment and closed the life chapter entitled “France.” People say you shouldn’t make major decisions when you are bereaved. Aspa had heard this bit of wisdom, but she convinced herself that it didn’t apply to her because she had been missing the island, its terebinths, and her father for years. She deceived herself into believing that her decision wasn’t new, just a continuation, an attempt to move forward. She didn’t understand that mourning is a cocoon. Inside it you change, you develop different priorities and desires, often without relationship to the past. Her old self was buried along with father. Her new self had not yet broken out of the cocoon.

She wrote to Thomas that she would travel to Leros through Athens; she wanted the keys to the house and to see the family. His reply came three days later, proposing that they meet the Sunday of her arrival at Zonar’s café. He didn’t offer to pick her up from the airport nor to host her at his house, nor did he mention a room at the family hotel. Aspa swallowed the chilly response and accepted. At least she would meet her nieces and nephew. She waited forty minutes at the airport for the metro into Athens. She waited again when the train stopped for unexplained reasons between Pallini and Doukissis Plakentias and then a second time between Holargos and Ethniki Amyna — delays that made her wonder to what Third World country she had returned. She finally got off at Monastiraki, left her bags in a cheap rented room, grabbed the children’s gifts, and went to the appointment without showering or changing clothes.

The renovated Zonar’s bore no relationship to the patisserie of fallen glory that Aspa remembered. The booths with synthetic beige leather that stuck to her bare legs had disappeared. In their place were high tables with bar chairs, the kind that hurt one’s back. Aspa sighed and requested a table for six outside, beneath the plane tree and beside the flowerboxes with white cyclamen. Maybe the kids would like to play, she thought. It was a halcyon day after all, with the sweet air of Athens announcing that spring had preceded winter. Aspa put her handbag and the gifts on the seventh chair, the only one that would remain empty, and sat down. The waiter asked if she would like something to drink. Aspa said, “No, I’ll wait for my family.” And she waited thirty-seven minutes until she heard Thomas’s voice, strangely strong, as if he were reprimanding her: “Aspasía!” Her brother was wearing summer shorts and a sweatshirt. His brush cut had receded. He resembled Grandpa Thomas, who had emigrated young to Alexandria and returned to Greece with twice the forehead.

Aspa stood and opened her arms. “Hello, brother.”

Thomas sat across from her without an embrace or a greeting.

Aspa lowered her arms. “And the kids? Εrsi?”

“They couldn’t come. Football, taekwondo, ballet, shopping.”

Aspa sat, looking at the empty chairs and the gift bag. Thomas put his hands on the table. They were tanned. He wore a thick, classical wedding ring. She hadn’t gone to his wedding nor to the funerals of their grandparents.

“I’m not going to meet the children?” she asked.

“What do you expect? To return after so many years and have the same place in our lives as you would if you had never left?”

“They’re my nieces and nephew.”

“If you want a relationship with them, first you have to have a relationship with Εrsi and me.”

Aspa lowered her gaze to the cyclamen. “I didn’t come here to settle accounts, Thomas. I came to see you.”

“As parents, we have to protect our children.”

“From their aunt?”

“You can’t use Babá as a means of speaking to them anymore.”

Aspa looked up at the bare branches of the plane tree above her head. She bypassed the insult and her indignation and said, “Shall we order the chocolates that we liked as kids?”

“They don’t make them anymore.”

Aspa waved to the waiter almost as if she were saying save me from him. She ordered two coffees without sugar, then thought that Thomas might not drink the same coffee as he had so many years ago. “Did you want something else?”

Thomas raised his chin. “I don’t change.”

“Something sweet?” said the waiter.

Thomas knit his fingers in a businesslike manner on top of the table. “I don’t have time. Thanks.”

The waiter left. Aspa leaned toward her brother. “I came here from France to see you.”

Thomas put a hand in the pocket of his sweatshirt, took out a bunch of keys and put them in the middle of the table. “Babá’s house keys. I came to give them to you.”

“Then why did we meet here?”

“I work on Saturdays. It’s convenient.”

“If you’re in a hurry, we can meet again later.”

“Think about what you want, Aspa. You can’t come in and out of our lives.”

Aspa stiffened. “I never would have reminded you about what you said…” Go see if you can make it in the world and you’ll come back to us begging. But she couldn’t bring herself to repeat it.

Thomas — a dwarf eucalyptus with a hollow that would never shelter any orphaned animals — stood and said, “Have a good trip.” He pushed the chair backwards with a muscular calf, turned, and walked off.

The coffees came. On each saucer was a mint-flavored chocolate, the same that they had loved as children. Aspa took a sip of coffee but her heartbreak prevented her from drinking the rest. She paid and wished that Thomas could have chosen a cheaper place to leave her with the bill. He probably didn’t even think of bills, being used to everything for free at his father’s hotel. Aspa held a chocolate to her nostrils. It smelled of the Sundays that she and her brother had played beneath the table while their parents argued. She replaced it on the saucer and left.

On the flight the next day, somewhere over Syros, the thoughts began, airy sirens that sigh from the clouds instead of singing among the waves of the sea, provoking doubts, hesitations, nostalgia, death. By the time Leros appeared like a spoonful of unmixed coffee grinds floating on the water inside a copper briki pot, the voices began murmuring inside Aspa’s head: you’ve lost your nieces and nephews, they will grow up far away from you, they will be indifferent to you. Aspa replied silently: as much as I love them, they don’t belong to me, only a tomb belongs to me in the middle of the Aegean.

She swallowed the bitterness, piquant and hard like a terebinth drupe. She returned to her father’s empty house in Saint Marina. To the bed still strewn with the sheets upon which he fell ill; to the last newspapers thrown on the floor (who knew if he’d been well enough to read them); to the framed photos of the grandchildren; to the green soap on the tiled bathroom floor, which might have slipped from his hand just before he called the ambulance; to the Playboy magazines hidden beneath the mattress; to the little yellow papers stuck to the desk blotter, full of notes for the business management book that he would never write.

Aspa tidied and cleaned, tidied and cleaned. For breaks she would go outside to the terebinth. Only the male remained; the female had been cut nearly to the earth. Aspa asked the neighbors and her remaining relatives who had committed the crime. Nobody knew. Aunt Virginia said that the great terebinth was dried out but still standing after Marínos’s funeral. Madame Calliope, who had filled her neighboring garden with sun-loving hibiscus and rose bushes, said that she hadn’t seen anything; when she returned from wintering in Athens, she discovered that the tree had been cut in her absence. At least the male survived, thought Aspa, although terebinths need the opposite sex nearby to flourish. Let time pass, maybe it will grow again. Even terebinth stumps can sprout. They are holy seeds. So says the book of Isaiah.

Neighbors and relatives asked Aspa what she planned to do on the island. She said she would rent a few rooms of the house in the summer. She would also open a café and shop on the ground floor for the therapeutic botanical infusions, tinctures, and extracts that she planned to sell. “It’s not going to catch on,” said Madame Calliope with repeated tsouks. “The rooms are easy money if you’ve got a good cleaning lady. But what do you want with herbs? The town has a pharmacy. We aren’t as backward as you think.”

“You’ll be disappointed,” said Aunt Virginia, who spent half her days neck-deep in the sea with only her hat above the water, red like a buoy. “People want freddo, not mountain tea.”

“And you expect to earn money from that?” said Uncle Stamátis, a retired employee of the Leros Psychiatric Hospital, at which he had suffered a breakdown watching the naked, abandoned patients lying on the bare cement of the yard beneath the burning sun and the freezing rain. “Come on, get yourself a real job with a salary. Ask your brother for a nice position.”

Aspa didn’t pay any attention. She’d grown tired of the living. She buried herself in the two-story neoclassical house with sky-blue shutters and a balcony woven with honeysuckle. Without applying for permits that she couldn’t afford, she secretly converted a back room into a professional kitchen where she could prepare botanical medicines. Whatever she had put aside working two decades in France as a landscape architect was spent on tiles, labor, plumbing, appliances, electrics, and tools. She worked in the yard while the carpenter worked in the kitchen. She trimmed, weeded, gathered olives and rotten drupes, and got rid of anything unwanted. In three months, the forest of green onions, geraniums, blackberries, laurels, guavas, olive trees, and one lonely terebinth became a garden.

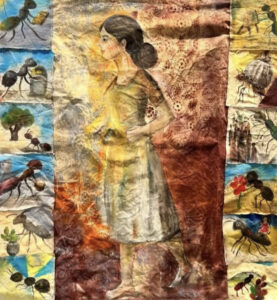

Still, she was disturbed every time her eye fell on the stump of the cut tree. She thought that perhaps she should take an ax and try to remove it. But she didn’t have the heart. Even if it was dead, it was hers. She postponed its exhumation. Around it, she planted and transplanted valerian for insomniacs, mint for gastroenteritis and neuralgia, great mullein and anise for bronchial catarrh, rosemary for hair growth, parsley for urinary and menstrual troubles, marjoram to induce appetite, colorful hollyhocks for coughs, palliative lemon balm, mallow for skin inflammations, oregano for healthy gums.

On Saturdays she would visit her father. She put narcissus, lemon flowers, and roses in his marble vases. She would sit on the grave ledgerstone, on the edge of the cliff above the sea and the town. She would stare at the lazy hoopoes, visitors from Grandpa’s Egypt, and say “Ach, Babá, if only I’d been born a boy, you would have loved me more.” She realized that she’d been searching for her father her whole life. She searched for him by avoiding him and abandoning him. She loved him so much that she fled as far as she could in order to avoid the pain of being near him and not having him. That was the reason she didn’t speak to him for nine years, although she didn’t understand it until they buried him high up in Saint Marina where he would see the whole Aegean until the Resurrection.

When the workmen finished the rooms and the kitchen, Aspa applied for a health trade license. She hoped the fifteen-day deadline would pass and that the license would be granted automatically without inspection, but along came a civil servant in the mood for an outing. He knocked at her door and announced, “Routine inspection.”

A cottonwood tree, thought Aspa, with a good height and a strong trunk; surely, he will make a mess of the place by leaving annoying cotton wisps everywhere. Her stomach was so upset by the sight of him while he checked faucets and ventilation that she went into the garden to cut a bouquet of mint. Look here, she thought, something that hasn’t changed in the least during my long absence: the noose of the state. To her surprise, the inspector finished in five minutes. “All perfect, congratulations,” he said, stepping outside. “After a few days the license will be issued.”

“I passed?” Aspa murmured.

“Sounds like the stress gave you a cold. Put some honey in your tea for your voice. I won’t ask if you’ve done a rapid test, although I hope so.”

Aspa forgot the tea and accompanied the punctilious inspector — good riddance. As he proceeded toward his car, he pointed at the terebinth stump. “Do you have the written approval of city council for the felling?”

“I inherited it like that.”

“Did you go to the city planning commission?”

Aspa felt shame and injustice. As if father were scolding her for the noise that Thomas had made. She said, “I’m a landscape architect, sir, and I’d never cut any tree, let alone that one. I played in it as a child.”

“Got it. A thief cut it down by night. What kind?”

“Ramithiá.”

“I can’t hear you, Ms. Pagóni. Louder please.”

“Terebinth.”

“A protected species,” he sighed. “It has to be reported to the city planning commission.”

Aspa hadn’t been wrong. The man was a cottonwood.

“But I inherited it like that,” she said.

“You inherited an offense in that case. Open your café, but I’m obliged to report the tree felling to the proper authorities.”

In the end Aspa needed the mint tea in order to digest the fact that she had inherited an offense. Tossing and turning in the heat, she didn’t manage to sleep that night. We’re having a swelter, she thought, in the middle of May, nature has gone insane. She went out into the yard barefoot and looked at the thermometer: 21ο C. The swelter was inside her. She walked the garden paths. She’d always loved the feeling of moist soil beneath her feet, even though she feared stepping on insects. The neighbor’s rooster crowed before his hour. Aspa sat on an iron chair that she’d set out for future customers, across from the stump of the female terebinth. She whispered, “The bureaucracy will drag on. You’ve got some time. Give me a sprout.” She ran her hand along the cut wood and added, “You haven’t dried out yet. Come on, you can do it.”

Over the next few days, she hired a young woman from Rhodes who had plans of becoming a veterinarian, as well as a Moldavian woman, married on the island, who spoke the heavy Leros dialect that Marínos Pagónis had disdained. They set up tables beside the flowerbeds, around the gaváfa-guava trees and beneath the male terebinth. They opened the cafe, worked hard and happily. The place became known. Italians and Germans from Patmos, Turks from Bodrum, Greeks from Athens, as well as various foreigners came to buy drupe soap, anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic extracts, decoctions and essential oils of guava leaf.

One July morning Lola showed up. She admired the garden so much that she almost forgot the duty with which she had been charged by the city planning commission. Beneath the dome of the widowed male terebinth, and between on-the-house treats of sugared guava and chamomile tea, Lola lit a cigarette. She chattered about yoga, vitamins, vegetarianism, and her failed attempt to give up gluten despite having been diagnosed with celiac disease. Aspa prayed that the visit would end without a true inspection, that the felled ramithiá would be deleted from the state files, but Lola put out her second cigarette, exhaled the smoke with an unexplained giggle and said, “Let’s see the stump while we’re here.”

It no longer showed behind the violet hollyhocks, the anise stalks crowned with bridal flowers, the upside-down pink valerian umbrellas and the yellow mullein that Aspa had gathered from the edges of country roads. Lola — a woman like a thorny acacia — stood up and pressed her lower back with her hands. “It’s too bad you opened the café, otherwise we wouldn’t have learned about the tree affair. And if it weren’t a protected species, we could forget the whole thing after another tea. Where is it?”

Aspa gestured to Flora, the Rhodian waitress, to bring more treats. That was how they communicated; with gestures instead of voices so as not to bother sleeping guests in the rented rooms. Aspa approached the felled ramithiá in the hope that the tree might have put forth a sprout. But the stump was still motionless, aching, and dry.

Lola lit a cigarette. “I have to report it to the forest department. Anyway, find an arborist to submit an application for felling and plant another in its place. That way you’ll probably get out of the fine.”

“Until a year has passed, we don’t know if it’s really dead,” said Aspa.

“Dry,” Lola corrected. “I assume you’ve lived outside Greece for many years because you’ve forgotten your language. Stumps like that can’t be resurrected, sweetie. I studied agriculture. I know.”

Aspa kept silent to avoid provoking more problems. In the evening, she wrote the required report, but she had trouble limiting herself to bureaucratically acceptable expressions. It is said that the terebinth in question dried out, she wrote, but she knew that terebinths almost never dry or wither. Nor do they burn. There was a reason that the Ancient Hebrews considered it a sacred tree. It was cut on an unknown date by an unknown hand after the death of my father, Marínos Pagónis, before I inherited the property. Also a falsehood. Her neighbor Madame Calliope surely knew and wouldn’t say. Nobody cuts that sort of tree nor does he remove the wood unnoticed, and Madame Calliope was a human potted plant, always on her balcony, no visits to Athens. Unable to hold back, Aspa added the following: the tree unfortunately was born female, whereas its owner Marínos Pagónis would have preferred two males. The tree surely suffered from sexism and a lack of love. She didn’t erase the last sentences. She left them as is and sent the report with a copy of the topographical chart, in which the positions of the trees were noted, both that which had been cut and that which remained.

At the end of July, at about noon, when the café was full of foreigners, a man parked his car beside the male terebinth, rolled down his window halfway and called out to the Moldavian cleaning lady, Elena, who was passing by with a basket of clean sheets, “Is Mr. Noulas here?”

“I didn’t understand,” said Elena.

Aspa heard this above the kitchen noises and the muffled conversation in the garden. She went out, wiping her hands on her apron, and saw a man with a crooked nose. He was standing behind the open car door with his foot on the sill, reading from a folder, which he tossed onto the passenger seat as soon as he heard Aspa’s welcome. “The folders got mixed up,” he said. “And I thought, on a property of this size, it’s impossible for somebody to cut nine pines by night along with one in the neighbor’s yard. Noulas is in Kos, not Leros. Are you the owner here? Aspasía Pagóni?”

Aspa nodded yes. The man closed the car door behind him. “It’s too bad you forced us to make a trip when you could have solved the situation by yourself. I’m in a hurry. I’ve got to leave on the afternoon boat. Show me, please.”

Aspa took him to the ramithiá and pushed back the surrounding plants as if she were uncovering a sleeping infant. “I didn’t cut it,” she whispered so that the customers wouldn’t overhear.

“I know. I read the crazy stuff you wrote.” The forest official pointed at the stump with his marker. “Get rid of it already, plant another one and we’ll close the case.”

“Impossible. It could still spr —”

“Where did you study?

“Athens.”

“I wouldn’t have guessed.”

“That tree was my world when I was a child. I didn’t cut it down and I won’t remove the stump until a full year has passed.”

The forest official squinted his eyes in the sunlight. “The decision isn’t mine. It belongs to the director. They’ll inform you.”

You are a crooked, misshapen pine, thought Aspa.

On the twenty-seventh of August, the decision arrived: the payment of a 1,050 euro fine and replanting were required in order for the offense to be cleared. Cursing silently, Aspa went out into the garden full of customers and said to the stump, “I won’t betray you. Devil take the money.”

She left the café in Flora’s hands, traveled the next day to Rhodes and paid the fine in person. The same twisted character who had come to Leros drew a line on the receipt with a red marker and asked, “Did you replant?”

“Come and see,” said Aspa, already on her way out.

The morning trip to Rhodes had passed with orders and other computer work. The evening return trip was another story. Aspa had deflated from her anger with the forest authority and the unknown murderer of the ramithiá. Before her were six hours and twenty-five minutes in the Aegean, which would be interrupted by only two stops, one in Symi, at the time when the heat gives way and the aroma of coffee floats out from behind half-closed shutters, and the second in Kos, evening already, with music playing in the tavernas where tourists devour previously frozen calamari and boiled greens reheated in microwaves. Aspa decided that she had to do something. She would invite Thomas to Leros. He would probably say no. But a no was more easily digestible than going to Athens for another plate of rejection. Between the islands of Kalymnos and Kalolymnos, she sent the message. No reply. An hour later, she called. Her brother didn’t pick up. Aspa held the phone in her hand until the boat neared Leros. No electronic melody broke the rumble of the boat nor the rushing of the sea.

In the morning, while Aspa was frying langítes doughnuts (which she no longer called loukoumádhes, even when speaking with Athenians), Flora entered the kitchen and shouted, “Come see!” She took Aspa by the hand, led her to the cut ramithiá, pushed aside the yellow mullein, and displayed the three sprouts that had emerged from the stump, two near the cut and a third down low, almost from the soil.

“My daughter ramithiá,” said Aspa. “Ramithiá, my daughter.”

Nektaria Anastasiadou is presently writing a historical novella.