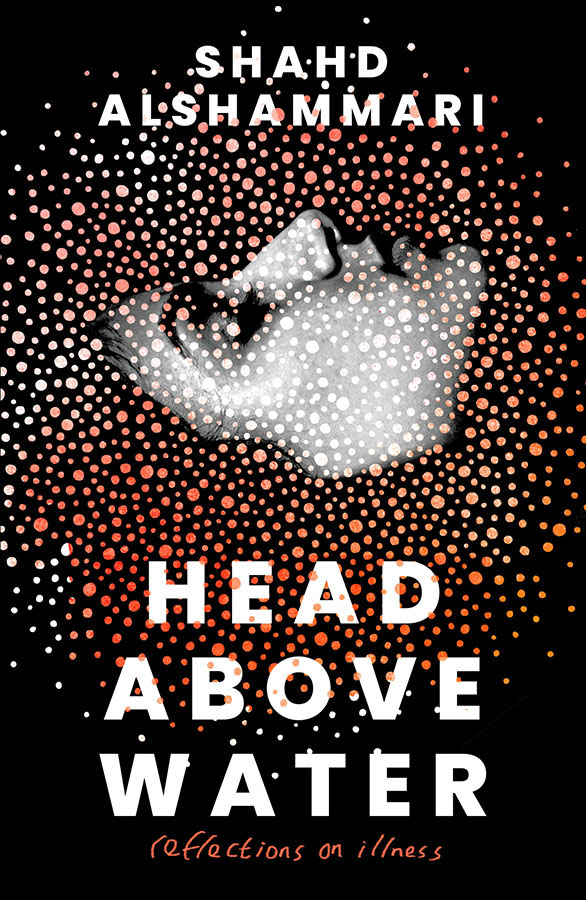

Head Above Water: Reflections on Illness

Neem Tree Press 2022

ISBN 9781911107408

Tugrul Mende

Researchers have been studying multiple sclerosis (MS) for more than 150 years, yet the cause of this autoimmune disorder remains unknown. As the Mayo Clinic notes, the body’s immune system attacks its own tissues, destroying the fatty substance that coats and protects nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord (myelin). The resulting symptoms manifest themselves so randomly that those who suffer from MS never know quite how tomorrow will turn out. Treatment therapies exist, but MS remains beyond definitive cure. In 2015, it was estimated that more than two million people globally were affected by this disease.

Far more information is available on multiple sclerosis in English and other European languages than in Arabic. Even though Shahd Alshammari’s Head Above Water is written in English, it attempts to fill a void with its complex narrative on disability and illness as experienced by an Arab woman, one who has spent most of her life in an Arab country.

Shahd Alshammari was 18 years old and living in Kuwait when her neurologist told her that she would die young. In Head Above Water, she describes her subsequent journey with MS. But it is not only her journey; this book reflects on how illness and disability are treated within society and in literature. Throughout, Alshammari addresses exile, feminism, and ableism. The book is not so much about the author’s illness, but about how to deal with one’s disability in a society that tries to hide most such afflictions. What makes Head Above Water a must-read is not only the fact that it engages with MS in a broader sense, but that it teaches you that while you may have to grapple with your own disabilities and illnesses, you are often still able to do the things you intend to do.

Storytelling is an important aspect in Alshammari’s narrative, a tool for her to address our lack of awareness with her own anecdotes.

Conversation features in each chapter, between Alshammari and her student Yasmeen as well as with others. An essential aspect of the book is the way the author not only gives voice to herself, but to others whose lives have been affected by illnesses and disability. Indeed, Alshammari shares the stage with people facing similar challenges, seemingly unconcerned that they might steal her thunder.

Alshammari starts out, “Stories are who we are. Stories make up our most vulnerable moments, and in storytelling we have the power to gain a sense of agency over our lives.” She begins her conversations with Yasmeen, who is an integral part of the book. The reader becomes involved through these conversations, which evolve into a complex narrative of patriarchy, colonialism, literature, and academia.

The book is also about exile, and what it means to leave home twice. Alshammari’s maternal grandmother Sahar was one of the first Palestinian teachers in Kuwait, back in 1949, and she had cancer. Her family experienced exile twice, because members of the Palestinian side were forced to leave Kuwait once it regained its independence from Iraq following the Gulf War and began punishing Palestinian residents for their perceived pro-Iraqi stance. This left a mark on Alshammari’s life. She quotes Edward Said: “Exile is strangely compelling to think about but terrible to experience.“ This is meant not only as physical exile but as an exile of the body from a mind that sometimes wants it to do things it cannot do.

The author continues:

One theme kept emerging, but I wanted to write all the themes down while I still could. Or perhaps get someone else to write them down. Whatever the case, they were bound to be written. So many journals, so many notes, and there had to be a place for them. It didn’t matter who would read them. Pain had to be exorcized. A huge part of my life had included carrying stories and wondering where they belonged.

Alshammari’s book is divided into four parts, each consisting of several chapters. Except for chapters one and two, they all begin with diary and blog entries, from which conversations with Yasmeen grow. “Language has failed me, but worse, I have failed language. I constantly feel misunderstood,” the author writes. The narrative switches between the diaries and what Alshammari develops from those blog entries.

The title of the book suggests that not everything in life is black and white, and not everything gets a happy ending. Yet the book is certainly not bleak; it tries to reflect on illness in a way that gives people a reason to continue reading. It also tries to make you understand that we in society have much work to do in order to learn how to properly and sensitively interact with those who suffer illness or disability. Even when the author was abroad, studying in England, she struggled not only with her MS, but with the fact that she wasn’t born there. She faced resistance as someone with MS, and a foreigner at that, who had gained admission to the universities of Exeter and Kent:

Academia looked difficult and had no place for people like me. It said so in the University regulations. If I wanted a scholarship, I would have to be fit and free from “issues.” There was a medical report that had to accompany your application. I wasn’t able to do that, and for the first time, I felt rejected by a larger entity than a man. The culture of academia presumes those best suited for academia are people who are abled-bodied and can demonstrate discipline and productivity. There is no place for anyone who doesn’t have autonomy and can’t keep it together always.

She persisted and showed that it was possible to be successful in academia. Some of this was thanks to fellow student Hannah, who became her constant companion during the years in England. Literature was the thing that brought them together and through which they bonded. With each chapter, Alshammari’s observations expand into the academic world of England, up to the point where she manages to finish her PhD. In addition, the narrative combines her academic world and the world of her family, a major component of her story, particularly her mother and grandmother. Alshammari describes how people react to disability and illness and what this means for her not only in academia but in her private life as well.

As noted above, there is a paucity of books in Arabic that deal with illness and disability While some deal with cancer and other common illnesses, rare maladies tend to be absent in literature, especially insofar as female writers are concerned. This is true of both Arabic-language fiction and nonfiction. Head Above Water was not written in Arabic, but by virtue of its author’s identity and her life in Kuwait, it may spur publication of Arabic-language books on the subject of disability. At any rate, Head Above Water tackles illness and disability, particularly as it affects a young and ambitious Arab woman, with warmth and determination.