Select Other Languages French.

A conversation with Mohammad Kassem, co-curator of the Kuwait Pavilion at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale.

A conversation with Mohammad Kassem, co-curator of the Kuwait Pavilion at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale.

The curator of this year’s Architecture Biennale in Venice, Carlo Ratti, introduces his chosen thematic INTELLIGENS. NATURAL. ARTIFICIAL. COLLECTIVE. with the statement: “To face a burning world, architecture must harness all the intelligence around us.” The Gulf States have some of the hottest climates in the world and their pavilions deservedly received much attention with Bahrain’s Heatwave curated by Berlin based Andrea Faraguna, awarded the Golden Lion for Best National Participation. These continue to be exciting years for architecture in the Gulf, with stellar museum projects that need no introduction. Qatar’s pavilion, curated by Aurélien Lemonier and Sean Anderson, designed by the Paris/Rotterdam based architectural studio Cookies, features work by 30 architects including giants such as Jean Nouvel. Interestingly, it also features the pioneering National Museum of Kuwait that was built in the 1980s, designed by the French architect Michel Écochard, too often omitted from media and academic depictions of the current Gulf museum boom.

Indeed, far from the crowds and press at the buzzing Arsenal and the elegant League of Nations at the Giardini, the Kuwait pavilion in the north of the city near the Citadel and city wall, and the accompanying catalogue, impress with a very different atmosphere. A team of young architects, artists, academics and botanists, the majority Kuwaiti nationals, the others all residents in the country, invite us into Rethinking Kuwait: Kaynuna.

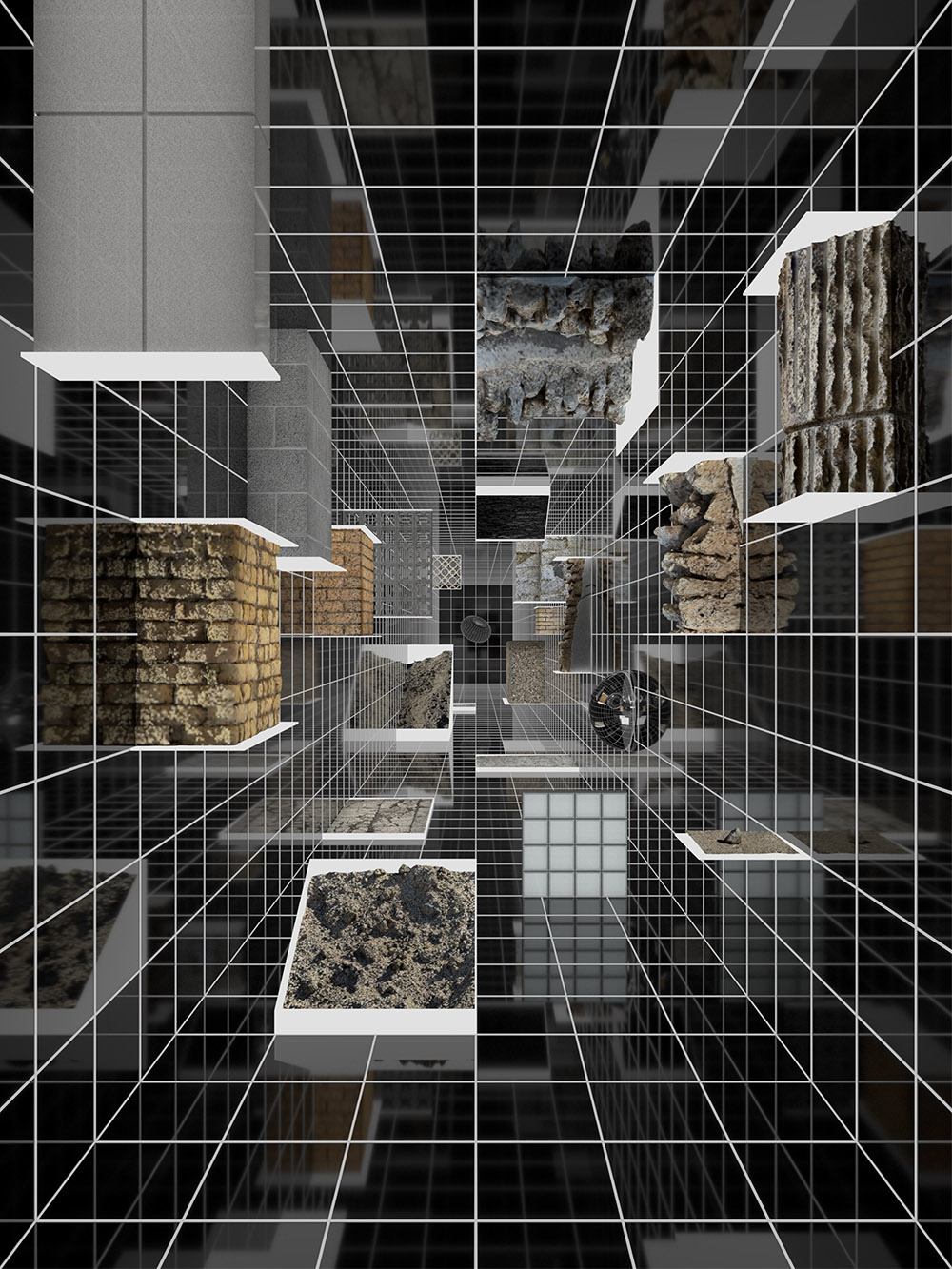

It is an ambitious project of considerable breadth. Arriving at the venue in the blistering heat that is Venice late June, I found the entrance somewhat unprepossessing; the visitor crosses a makeshift courtyard with grass over-growing abundantly before reaching a large warehouse looking out at the shipyard opposite. But once inside, the scale of the double height space with its exposed beams, silence and cool air, and the quality of the work on display, invites you to stay. The bold scenography of display cases with distinctive blue glass echoed in the accompanying text panels hints at museum lexicography, while the hanging inflatables remind us this is a temporary exhibition. The extensive, thought-provoking texts accompanying the exhibits suggest this is an exercise in investigation and reflection, as much as display.

I spoke to Mohammad Kassem, co-curator of the pavilion, who explained this is the second Venice pavilion by RRK (Rethinking Rethinking Kuwait), a collective that came into being for the 18th Biennale under the theme “Laboratory of the Future.” They had wanted to create an experimental practice to work both top down and bottom up; to address policy and governance while simultaneously reflecting on the actual experience and implementation of this policy. Interestingly Kuwait’s National Council of Arts and Letters, which commissioned the pavilion, also chose to make the work in-house; almost all of the members of the curatorial team are Council employees. For the 2023 participation, RRK investigated the pre-post oil transition in shaping the urban habitat, and wanting to move away from the “great demolition” culture of Kuwait 1960s, proposed a non-invasive and non-destructive approach to building new, much needed collective transport systems. That pavilion subsequently showcased in Kuwait with Dar Al Athar Al-Islamiyyah at Yarmouk Cultural Centre, where it was a symbol of the heightened level of discourse around urban planning and architecture, at times uncomfortable, that Mohammad says is taking place in his country. He hopes the 2025 pavilion will migrate to the Kuwait national museum, and it is clear that the work is designed to serve a dual function: a window onto the Gulf State for visitors to Venice, and a window into an imagined possibility for those living in Kuwait. This duality, captured in the mirrors that reflect the scenography back at the viewer, resonated throughout my visit.

In response to this year’s theme RRK arrived at Kaynuna (the closest English translation is being). I asked Mohammad to share what Kaynuna means to him. His reply was complex:

“The concept emerged from our questioning of the roots from which things emerged, whether positive creation, dysfunctions of bureaucracy or discordances of policy and implementation, a general term neither positive nor negative, trying to find the core whether physical as in buildings, or ideas as in policy. In relation to the theme of ‘Intelligens.’ It seeks to create a non-binary toolkit.”

This is important in a region that has become known for masterpieces by international star architects alongside easily digestible heritage projects. Mohammad says his team wants to take this discourse beyond such a binary approach. “To be flexible in our contemplation and pursuit of solutions by looking for the real origin of the question in hand, the essence rather than the by product.” As such the catalogue is rooted in the reality and history of Kuwait, be it policy, climate, man-made structures or natural habitat, and each architectural question is dealt with individually. No one approach fits all. This is commendable but for the outsider, it is arguably a lot to digest in one visit.

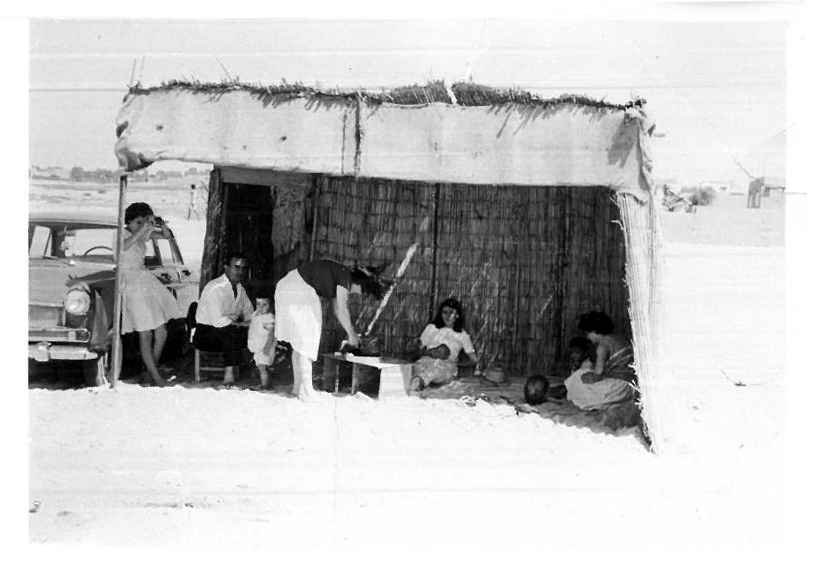

Looking for an entry point to our discussions, I turned to a subject that had impressed me when I lived in Kuwait, and never seems to fail to impress people new to the country: the generosity and reach of its welfare state. It is an architectural construction in its own right, from generous university scholarships and pensions, to healthcare and housing. A physical embodiment of this is the “jameia” or humble “co-op.” Kuwait is divided into residential and non-residential districts. Each one contains one if not several “co-ops,” which to this day distribute “tamween” — free monthly basic food supplies to every Kuwaiti household. Mohammed says they asked themselves, is the current state of the jameia “a litmus of… where we are as a culture and are we content with it? If we wanted to reclaim it meaningfully, is this only about our wealth or about localization and grassroots, of which the latter is the sustainable solution.” He added that he also wanted to show visitors a piece of the real Kuwait. “Too often at the Biennale, there is a kitsch folkloric representation of culture. The Souk has been a victim of this heritage-based architecture and become exquisite shells, whereas the co-op remains a real hybrid.”

In their drawings for an imagined “Reclaiming the Jameia,” on display at the Pavilion, RRK highlight the role these spaces have played in communities, and propose to use them as platforms for local industry while referencing the souk in semi-covered pedestrian areas. It is part of a bigger project to create a language to define their Welfare Nation and to map the areas to determine which lack what, and create a localized language to describe such needs. I asked where they were with the project. “Everything in the expo is a seed to initiative dialogue,” he explained, “to mobilize debate around the question of social and architectural town planning.”

It is also a window into this fascinating society.

“We propose distinguishing between ideas and values, where ideas often align with visual indicators and folklore representations of culture, values are liberated from the limitations of communication, and are susceptible to transformations and mutations.” Catalogue

This question of values took us to a discussion of heritage. The exhibition examines the traditional courtyard house. Mohammed explains: “We have municipal codes that make it difficult to go back to the old courtyard house, however we asked what was the performance of that architecture that is relevant today.”

He explained that you can find houses in Kuwait with windows facing the street whose shutters are permanently closed for reasons of modesty and privacy. Not only must this make the interiors dark, it also leads to cooling loss through the glass. These windows are then essentially decorative, in line with an international aesthetic that is at odds with certain cultural values. The solution, he explains, is not to return to a courtyard as the residential areas are divided into small lots that would make any courtyard more of a light-well than a useful space; instead RRK looked for a performance-based solution to deal with this tension around aperture and how to create screens and layers. Their proposal will be presented to the municipality in the next few months as a new solution to both climatic and cultural issues.

This question of buildings suited to both the climate and the culture reminded me of the Kuwait Brutalist architecture that had so struck me when I first moved there in 2002. Residential houses and iconic buildings from the 1950s through to the 1980s such as the late ‘50s Al-Ahmadi Souk (currently being restored/renovated through the Ahmadi Cultural Platform) with its shaded walkways and angled windows to protect from the glaring sun, felt to my then outsider’s eye as some of the most successful post-oil buildings. Mohammad agreed and explained that in the exhibition they explored the Kuwaiti Brutalist architecture as a mutation of the Kuwaiti mud house.

“Brutalism was a post-war response to the decimation of certain European cities. Since Kuwait was not impacted from the same point of view, a mutation happened. The style became about thermal regulation, since massive concrete elements create a kind of enclosure, while the design of setbacks under massive buildings created shade for walkways in the city. Contemporary concrete is often grey, but in Kuwait they have a sandy limestone quality that connects well to the visual ecology. They explored apertures that are narrow and angled to accommodate the sun, and have a natural orientation to the north because of the solar path. This was not just an aesthetic exercise, there were deep intentions behind it. We looked at this movement not through a time frame, in Kuwait architecture is not generated through sequential frames as the local cultural adoption is devoid of architectural intention, rather from a different kind of sincerity, being an essential part of the landscape, and a successful adaptation of an international style that seems intrinsic rather than imposed. These buildings often reference the courtyard, the desire to have a memory of a space rather than a kitsch reconstruction.”

I was always saddened when I saw one of these iconic buildings abandoned, and unfortunately many are being demolished. The exhibition ends with a call for a rationale around demolition and preservation and the establishment of the Kuwait Heritage Conservation Agency (KHCA). At this stage, it is a speculative proposal that Mohammad believes is within the realm of the attainable. Not a substitute for the National Council but an entity that works with it. He stresses, “You note that at the pavilion we don’t talk about it since the exhibition is from the perspective of the KHCA. This is an imagined retrospective, what people in decades to come might present as a portrait of Kuwait architecture in 2025.”

Per the accompanying catalogue, “Understanding cultural identity in architecture requires looking beyond government-imposed styles and monumental structures to the lived experiences that shape the built environment. Culture is defined by people, not by authorities, and architecture manifests societal values shaped by human interaction with space over time. By analyzing architecture through the lens of its users, builders, and local adaptations, we can better understand how spaces evolve to reflect the cultural psyche of a community.”

My next question was about the level of collaboration between the various Gulf countries around architectural solutions. “The goal is always to find a regional dialogue where we are not repeating things or wasting efforts to find solutions. But there is also a different climatic condition. Bahrain’s pavilion is a fantastic solution for their locale, but Kuwait does not have the humidity and condensation, and it might not work and you are spending energy and resources trying to force a system that is not natively inclined. But the conversation is not irrelevant. It is worth the pursuit to reduce the amount of energy both physical and for research. It’s the same in the arts scene — we need more cross-pollination… things are not universal but there is enough similarity that we could have meaningful discourse if we could find that common language. But I don’t think the language is there yet.”

Reflecting on this last comment, I returned to the question of the Kuwait National Museum that had been a pioneering and prototypical model in the Gulf when it opened in 1983. The museum was badly damaged during the Iraqi invasion. Mohammad explains its presence in the Qatar pavilion: “[Our museum] was a significant leap that happened.” In terms of RRK’s studies on it today, he says, “Like it or not from an aesthetic point of view is never the conversation, that it is international or foreign was not what we were interested in. Rather we looked at the concept of the museum as a global entity, a tool used for nation building through cultural conservation and dissemination of cultural identity and heritage.

“It’s unfortunate because of the damage that was done during the invasion, our museum was reduced in its operational scale. Since a museum is an entity about conservation, which is very much in line with Intelligence as an idea, and is also relevant to the region because we use it as a reference to ask, what is the history we are trying to express through this institution and what are the tools and techniques that we use? So the showcases begin to appear in our pavilion design: national pavilion, national museum, national identity, begin to coalesce, and you are talking to an international audience so it needs to be accessible to the point they feel at ease in the space, but at the same time it challenges your conventions and normalcy. There is no universal definition of what a museum is… and each country creates their interpretation of what this institution represents.”

He hopes the pavilion will return to the National Museum to close a full circle on the museum-type scenography in Venice, and also to serve as “an introduction for future projects, planting seeds where different authors and contributors can pick up on an idea and pursue it… This is not a solution, rather an introduction to a method of thinking and a framework. We are not in a position to propose totalized and idealized solutions, I don’t think anyone is…”

Thinking about the broader art scene in the Gulf as I write these words from the Avignon Festival, whose invited language this year is Arabic, I note that there is a conspicuous absence of voices from the Gulf in the performances, films and poetry selected here, apart from as financial sponsor of two events. I would argue that this is far too often the case at European arts festivals. What we see at this year’s Venice Architectural Biennale clearly demonstrates the diversity and sophistication of research and work coming out of this region, and other arts organizations would do well to explore it.

I return to Carlo Ratti’s quote and the need to harness all the “intelligence around us.” A window looking outwards to one person is a window looking inwards to another. This team of passionate young local professionals, clearly rooted in the best of what was before them in all its forms, are just such an “Intelligens” and “Collective,” whose voice most certainly deserves to be heard.

Kaynuna is a commission of the Kuwait Council for Arts and Letters. Curated by Mohammad Kassem, Hamad Alkhaleefi, Nasser Ashour and Rabab Raes Kazem. Exhibitors include Ahmad Almutawa, Alya Aly, Batool Ashour, Dalal AlDayel, Dana AlMathkoor, Danah Alhasan, Danah El-Madhoun, Essa Alfarhan, Fatemah Alzaid, Fatima Alsulaiman, Hasan Almatrouk, Haya Alfadhli, Haya Alnibari, Hussain Alkazemi, Khaled Alanjery, Khaled Mohamed, Nour Alkheder, Qutaiba Buyabes, Sakinah Muqeem, Zainab Murtadhawi.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)